Youth-Inclusive Mechanisms for Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism in the Igad Region a Case Study of Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report UNEP Dandora Environmental Pollution and Impact to Public Health

ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTION AND IMPACT TO PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS OF THE DANDORA MUNICIPAL DUMPING SITE IN NAIROBI, KENYA 2 Environmental Pollution and Impact to Public Health; Implication of the Dandora Municipal Dumping Site in Nairobi, Kenya. A PILOT STUDY REPORT NJOROGE G. KIMANI In cooperation with THE UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME (UNEP) Nairobi, Kenya, 2007 3 Cover Photo: Korogocho Children dancing during the Children day and inhaling toxic smokes from the Dandora dumpsite. Courtesy of Andrea Rigon Author/Editor: Njoroge G. Kimani, MSc Medical Biochemistry Clinical Biochemist/Principal Investigator Email: [email protected] In collaboration with; Rob De Jong and Jane Akumu United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Financial support for study made available by UNEP This document contains the original UNEP report. Kutoka Network has changed the layout and added some pictures with the only objective to facilitate the circulation of such an important document. Kutoka Network believes that this report is key for public health advocacy initiatives in Nairobi. For more information: www.kutokanet.com 4 Contents Acknowledgment 7 Executive Summary 8 CHAPTER 1 1 Introduction 9 1.1 Background Information 9 1.2 Solid Waste Management, Environmental Pollution and Impact to Public Health 10 1.2.1 Heavy metals 10 1.2.2 Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) 11 1.3 The Dandora Municipal Waste Dumping Site 12 1.4 Objectives of the Study 15 1.4.1 Broad objective 15 1.4.2 Specific objectives 15 1.5 Significance of the study 15 CHAPTER 2 2. Methodology and Results 16 2.1 Environmental Evaluation 16 2.1.1 Collection of soil samples and compost sample 16 2.1.2 Collection of water samples 16 2.1.3 Analysis of environmental samples 16 2.1.4 Results of environmental samples 17 2.2 Biomonitoring and Health Effects 20 2.2.1 Clinical evaluation 20 2.2.2 Collection of biological samples 22 2.2.3 Analysis of biological samples 22 2.2.4 Biological samples results 23 2.2.4.2 Urine samples 25 CHAPTER 3 3. -

Barriers to Entry: Entrepreneurship Among the Youth in Dandora, Kenya Alan Sears

Barriers to Entry: Entrepreneurship Among the Youth in Dandora, Kenya Alan Sears Student Research Papers #2012-6 THE PROGRAM ON LAW & HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Notre Dame Law School’s Program on Law and Human Development provided guidance and support for this report. The author remains solely responsible for the substantive content. Permission is granted to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use, provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and a full citation on the first page. The proper form for citing Research Papers in this series is: Author, Title (Notre Dame Program on Law and Human Development Student Research Papers #, Year). ISSN (online): 2165-1477 © Alan Sears Notre Dame Law School Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 USA Barriers to Entry: Entrepreneurship Among the Youth in Dandora, Kenya Alan Sears* University of Notre Dame Law School Program on Law and Human Development * This report was made possible through support form the University of Notre Dame Law School’s Program on Law and Human Development. The author is grateful to the Holy Cross Parish of Dandora for hosting him, to the Dandora Law and Human Development Project (Kerubo Okioga, Dorin Wagithi, Gerald Otieno, Andrew Myendo, and Christine Achieng) for their invaluable assistance and support, and to Professors Christine Cervenak and Paolo Carozza for their encouragement and advice. The author would also like to thank his friends and family for their love and support. The content of this report is the sole responsibility of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Program on Law and Human Development nor the Ford Family. -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

Tht KENYA GAKETTE

S - PDCIAL ISSUE ' . 'l* I N # >+ ; % ) - -- N s l A & * : B TH t K EN YA G A KETTE D blished by Authority of the Reppblic of Kenya (Registered as a NCWSIIaPC at the G.P.O.) , u. g u y u uu . usau u u Vol. CIV- NO. 42 NAIROBI, 21st June, 2002 ' Price Sh. 40 GAZE'IJE NcrlcE No. 3985 TIIE COMPANW S AW (Cap. 486) m coc on noNs IT IS notified for general information tht the following companies have been ,incorporated in Kenya during the perie , 1st to 31st August, 1998. PRIVATECOMPA- Name ofcompany Nolafvl Capital Address ofRegistered Olc: KSh. A. S. Abdalla & Sons Exporters Limited (Reg. No. 1(q(% Plot No. 1(X160, Dandora, Komarock Road, P.O, Box 82015) 77869, Nairobi. Sosiot General Stores L imited (Reg. No. 82016) 1œ .(m Plot No. 41, Sosiot Markeq Kericho, P.O. Box 856. Kericho. 3, Falcon Prom rties Limited meg. No. 82017) 1* ,(e L.R. No. 20W4281,.Commerce House, M oi Avenue, P.O. Box 79, Menengai. , 4. Moe lumt Africa Limited (Reg. No. 82018) 50,4* Block 5/113/Section lI. Nakuru Town. P.U. Box 13676, NAllm. Biochlor East Africa Limited (Reg. No. 82019) 1* ,(e L.R. No. 209/9326. Kimathi House, Kimathi Street. P.O. Box 53857. Nairobi. 6. C'ity Refrigeration :nd Air Conditioning Services ltX),(> Plot No. 209/13638, Ambalal Road, P.O. Box 32705. Limlted (Reg. No. 82020) Nairobi. 7. Daio Rejearch Assoiigtes Limited (Reg. No. 5* ,(* L.R. No. Nairobe lock 1> 327. Ushirika Estate, ofî 82021) luja Road; P.O. -

Internal Communication Clearance Form

PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions REFERENCE: AL KEN 2/2019 13 March 2019 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacity as Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 33/30 and 35/15. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information we have received concerning what appears to be a persisting and growing pattern of extrajudicial executions due to excessive use of force by Kenyan law enforcement personnel and other security agencies, in the context of combating criminality and terrorism. Concerns regarding alleged extrajudicial executions by police forces have been raised by Special Procedures mandate holders in two previous communications sent to your Excellency’s Government on 11 July 2017 (AL KEN 9/2017) and on 16 October 2017 (UA KEN 13/2017). We would like to thank you for your response to KEN 13/2017 from 18th October 2017 and await a “substantive response from relevant authorities in Nairobi”, as indicated by your Excellency’s Government’s letter. We respectfully urge your Excellency’s Government to provide us with replies at your earliest convenience to other letters previously sent regarding these and similar concerns. According to the information received: Instances of enforced disappearances, torture and extrajudicial executions by law enforcement personnel against youth in slum areas in Kenya have been on the rise, particularly during the past five years, surrounded and encouraged by what appears to be a general climate of impunity. -

Affordable Housing Provision in Informal Settlements Through Land

sustainability Article Affordable Housing Provision in Informal Settlements through Land Value Capture and Inclusionary Housing Bernard Nzau * and Claudia Trillo School of Science, Engineering and Environment, University of Salford, Manchester M5 4WT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 18 July 2020; Published: 24 July 2020 Abstract: Public-driven attempts to provide decent housing to slum residents in developing countries have either failed or achieved minimal output when compared to the growing slum population. This has been attributed mainly to shortage of public funds. However, some urban areas in these countries exhibit vibrant real estate markets that may hold the potential to bear the costs of regenerating slums. This paper sheds light on an innovative hypothesis to achieve slum regeneration by harnessing the real estate market. The study seeks to answer the question “How can urban public policy facilitate slum regeneration, increase affordable housing, and enhance social inclusion in cities of developing countries?” The study approaches slum regeneration from an integrated land economics and spatial planning perspective and demonstrates that slum regeneration can successfully be managed by applying land value capture (LVC) and inclusionary housing (IH) instruments. The research methodology adopted is based on a hypothetical master plan and related housing policy and strategy, aimed at addressing housing needs in Kibera, the largest slum in Nairobi, Kenya. This simulated master plan is complemented with economic and residual land value analyses that demonstrate that by availing land to private developers for inclusionary housing development, it is possible to meet slum residents’ housing needs by including at least 27.9% affordable housing in new developments, entirely borne by the private sector. -

Solid Waste Management and Risks to Health in Urban Africa: a Study of Nairobi and Mombasa Cities in Kenya

Solid Waste Management and Risks to Health in Urban Africa: A Study of Nairobi and Mombasa Cities in Kenya MOMBASA NAIROBI KENYA © Photo by Benedicte Desrus Solid Waste Management and Risks to Health in Urban Africa A Study of Nairobi and Mombasa Cities in Kenya African Population and Health Research Center Solid Waste Management and Risks to Health in Urban Africa: A Study of Nairobi and Mombasa Cities in Kenya 2 Solid Waste Management and Risks to Health in Urban Africa: A Study of Nairobi and Mombasa Cities in Kenya Table of Contents List of Tables v List of Figures v List of Equations v Abbreviations vi Acknowledgements vii Executive Summary viii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 2 1.2 The Urban ARK Programme 5 1.3 Overview of SWM Policies and Systems 6 1.4 Objectives of the Survey 7 1.5 Study Design and Approaches 8 1.6 Study Sites 10 1.7 Sample Design 10 1.7.1 The Sampling Frame for the Quantitative Survey 10 1.7.2 Sample Size and Determination 10 1.7.3 Sample Allocation 11 1.7.4 Cluster Sizes 11 1.7.5 Sample Selection 11 1.7.6 Computation of Sample Weights 12 1.7.7 Estimation of Population Parameters 12 1.7.8 Computation of Sample Standard Errors 13 1.8 Survey Tools 13 1.8.1 Quantitative Data Collection 13 1.8.2 Qualitative Data Collection 13 1.9 Fieldwork Procedures 14 1.9.1 Fieldworker Training 14 1.9.2 Fieldwork 15 1.10 Data Processing 15 1.11 Response Rates 16 1.12 Ethical Considerations 16 References 18 CHAPTER 2: CHARACTERISTICS OF HOUSEHOLDS AND RESPONDENTS 21 2.1 Background 21 2.2 Household Characteristics 21 2.2.1 -

Chapter 5: Nairobi and Its Environment

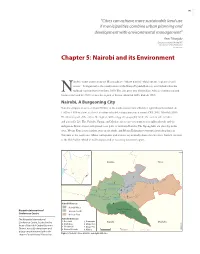

145 “Cities can achieve more sustainable land use if municipalities combine urban planning and development with environmental management” -Ann Tibaijuki Executive Director UN-HABITAT Director General UNON 2007 (Tibaijuki 2007) Chapter 5: Nairobi and its Environment airobi’s name comes from the Maasai phrase “enkare nairobi” which means “a place of cool waters”. It originated as the headquarters of the Kenya Uganda Railway, established when the Nrailhead reached Nairobi in June 1899. The city grew into British East Africa’s commercial and business hub and by 1907 became the capital of Kenya (Mitullah 2003, Rakodi 1997). Nairobi, A Burgeoning City Nairobi occupies an area of about 700 km2 at the south-eastern end of Kenya’s agricultural heartland. At 1 600 to 1 850 m above sea level, it enjoys tolerable temperatures year round (CBS 2001, Mitullah 2003). The western part of the city is the highest, with a rugged topography, while the eastern side is lower and generally fl at. The Nairobi, Ngong, and Mathare rivers traverse numerous neighbourhoods and the indigenous Karura forest still spreads over parts of northern Nairobi. The Ngong hills are close by in the west, Mount Kenya rises further away in the north, and Mount Kilimanjaro emerges from the plains in Tanzania to the south-east. Minor earthquakes and tremors occasionally shake the city since Nairobi sits next to the Rift Valley, which is still being created as tectonic plates move apart. ¯ ,JBNCV 5IJLB /BJSPCJ3JWFS .BUIBSF3JWFS /BJSPCJ3JWFS /BJSPCJ /HPOH3JWFS .PUPJOF3JWFS %BN /BJSPCJ%JTUSJDUT /BJSPCJ8FTU Kenyatta International /BJSPCJ/BUJPOBM /BJSPCJ/PSUI 1BSL Conference Centre /BJSPCJ&BTU The Kenyatta International /BJSPCJ%JWJTJPOT Conference Centre, located in the ,BTBSBOJ 1VNXBOJ ,BKJBEP .BDIBLPT &NCBLBTJ .BLBEBSB heart of Nairobi's Central Business 8FTUMBOET %BHPSFUUJ 0510 District, has a 33-story tower and KNBS 2008 $FOUSBM/BJSPCJ ,JCFSB Kilometres a large amphitheater built in the Figure 1: Nairobi’s three districts and eight divisions shape of a traditional African hut. -

TERRORISM THREAT in the COUNTRY A) Security Survey

TERRORISM THREAT IN THE COUNTRY a) Security Survey In 2011, the threat of terrorism in the country rose up drastically largely from the threat we recorded and the attacks we began experiencing. Consequently, the service initiated a security survey on key installations and shopping malls. The objective was to assess their vulnerability to terrorist attacks and make recommendations on areas to improve on. The survey was conducted and the report submitted to the Police, Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Tourism. Relevant institutions and malls were also handed over the report. Subsequent security surveys have continued to be conducted. As with regard to the Westgate Mall which was also surveyed, the following observations and recommendations were made as per the attached matrix. Situation Report for 21.09.12 - Serial No.184/2012 Two suspected Al Shabaab terrorists of Somali origin entered South Sudan through Djibouti, Eritrea and Sudan and are suspected to be currently in Uganda waiting to cross into Kenya through either Busia or Malaba border points. They are being assisted by Teskalem Teklemaryan, an Eritrean Engineer with residences in Uganda and South Sudan. The duo have purchased 1 GPMG; 4 hand grenades; 1 bullet belt; 5 AK 47 Assault Rifles; unknown number of bullet proof jackets from Joseph Lomoro, an SPLA Officer, and some maps of Nairobi city, indicating that their destination is Nairobi. Maalim Khalid, aka Maalim Kenya, a Kenyan explosives and martial arts expert, has been identified as the architect of current terrorist attacks in the country. He is associated with attacks at Machakos Country Bus, Assanands House in Nairobi and Bellavista Club in Mombasa. -

Global Migration Perspectives

GLOBAL MIGRATION PERSPECTIVES No. 47 September 2005 Formalizing the informal economy: Somali refugee and migrant trade networks in Nairobi Elizabeth H Campbell Binghamton University State University of New York [email protected] Global Commission on International Migration 1, Rue Richard Wagner CH:1202 Geneva Switzerland Phone: +41:22:748:48:50 E:mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.gcim.org Global Commission on International Migration In his report on the ‘Strengthening of the United Nations - an agenda for further change’, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan identified migration as a priority issue for the international community. Wishing to provide the framework for the formulation of a coherent, comprehensive and global response to migration issues, and acting on the encouragement of the UN Secretary-General, Sweden and Switzerland, together with the governments of Brazil, Morocco, and the Philippines, decided to establish a Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM). Many additional countries subsequently supported this initiative and an open-ended Core Group of Governments established itself to support and follow the work of the Commission. The Global Commission on International Migration was launched by the United Nations Secretary-General and a number of governments on December 9, 2003 in Geneva. It is comprised of 19 Commissioners. The mandate of the Commission is to place the issue of international migration on the global policy agenda, to analyze gaps in current approaches to migration, to examine the inter-linkages between migration and other global issues, and to present appropriate recommendations to the Secretary-General and other stakeholders. The research paper series 'Global Migration Perspectives' is published by the GCIM Secretariat, and is intended to contribute to the current discourse on issues related to international migration. -

Environmental Pollution and Impacts on Public Health

Environmental Pollution and Impacts on Public Health: Implications of the Dandora Municipal Dumping Site in Nairobi, Kenya Report Summary Based on a study by Njoroge G. Kimani in cooperation with United Nations Environment Programme and the St. John Catholic Church, Korogocho Urban Environment Unit United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi - KENYA. Telephone: +254-20-7624184, Fax: +254-20-7624249 Email: [email protected] web: http://www.unep.org/urban_environment UNEP promotes environmentally sound practices globally and in its own activities. This publication is printed on paper from sustainable forests including recycled fibre. The Photo: UNEP paper is chlorine free, and the inks vegetable- based. Our distribution policy aims to reduce UNEP’s carbon footprint. 1. Introduction Over the last three decades there has been increasing global concern over the public health impacts attributed to environmental pollution, in particular, the global burden of disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about a quarter of the diseases facing mankind today occur due to prolonged exposure to environmental pollution. Most of these environment-related diseases are however not easily detected and may be acquired during childhood and manifested later in adulthood. Improper management of solid waste is one of the main causes of environmental pollution and degradation in many cities, especially in developing countries. Many of these cities lack solid waste regulations and proper disposal facilities, including for harmful waste. Such waste may be infectious, toxic or radioactive. Municipal waste dumping sites are designated places set aside for waste disposal. Depending on a city’s level of waste management, such waste may be dumped in an uncontrolled manner, segregated for recycling purposes, or simply burnt. -

Community-Responsive Adaptation to Flooding in Kibera, Kenya ICE

Engineering Sustainability Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers Volume 170 Issue ES5 Engineering Sustainability 170 October 2017 Issue ES5 Pages 268–280 http://dx.doi.org/10.1680/jensu.15.00060 Community-responsive adaptation to Paper 1500060 flooding in Kibera, Kenya Received 30/10/2015 Accepted 03/05/2016 Mulligan, Harper, Kipkemboi, Ngobi and Collins Published online 06/06/2016 Keywords: developing countries/infrastructure planning/sustainability ice | proceedings ICE Publishing: All rights reserved Community-responsive adaptation to flooding in Kibera, Kenya 1 Joe Mulligan CEng, MICE, ACGI, LEED AP BD+C 3 Pascal Kipkemboi Associate Director, Kounkuey Design Initiative, Stockholm, Sweden Field Associate, Kounkuey Design Initiative, Nairobi, Kenya (corresponding author: [email protected]) 4 Bukonola Ngobi MA 2 Jamilla Harper MA Urban Design Coordinator, Kounkuey Design Initiative, Nairobi, Kenya Associate Director for Kenya, Kounkuey Design Initiative, Nairobi, 5 Anna Collins BEng (Hons) Kenya Volunteer Engineer, Engineers without Borders UK, London, UK; Civil Engineer, Arup, London, UK 1 2 3 4 5 Much of the world’s existing and future population will live in slums, where the twin trajectories of rapid urbanisation and increased flooding driven by climate change collide. Few spatial planning policies currently address this issue in practice. Poorly planned relocation from slum areas has caused conflict and insecurity, while large-scale infrastructural solutions for reducing flood risk are prohibitively expensive. There is a need to consider how local adaptation measures for increasing resilience to flooding can complement other structural and policy measures. This paper describes and evaluates autonomous, market-based and public-policy-driven structural and non-structural adaptation approaches to flooding in Kibera, the largest informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya.