Plasmacytoid Variant of Urothelial Carcinoma: Poor Prognostic Variant with High Expression of CDH1 Mutation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Original Article Characteristics of Incidental Prostate Cancer After Radical Cystoprostatectomy for Bladder Carcinoma in Chinese Men

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2016;9(3):3743-3750 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0021275 Original Article Characteristics of incidental prostate cancer after radical cystoprostatectomy for bladder carcinoma in Chinese men Guangxiang Liu1, Shiwei Zhang1, Jun Chen2, Xiaozhi Zhao1, Tieshi Liu1, Shuai Zhu1, Qing Zhang1, Weidong Gan1, Xiaogong Li1, Hongqian Guo1 Departments of 1Urology, 2Pathology, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, The Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, Institute of Urology Nanjing University, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China Received December 6, 2015; Accepted February 15, 2016; Epub March 1, 2016; Published March 15, 2016 Abstract: The purpose of this study was to analyze and characterize the clinicopathological features of incidental prostate cancer (PCa) after radical cystoprostatectomy (RCP) for bladder cancer in Chinese patients. We retrospec- tively reviewed 378 male patients who underwent RCP for muscle invasive bladder cancer at our center and identi- fied 47 men with incidental PCa. The clinicopathological data of incidental PCa after RCP were compared with those of clinical T1c PCas who had radical prostatectomy at our institute. Forty-seven of the 378 patients (12.4%) were diagnosed with PCa. The incidental PCa was well-differentiated in 68.1% of patients, compared to 33.5% of patients with T1c PCa, and was significantly more unifocal than the T1c PCas. When compared to T1c PCa, the incidental PCa was more likely to be organ-confined, have negative margins and be classified as clinically insignificant. After a mean 48-month follow-up, only one patient with incidental PCa was confirmed to have bone metastasis. While 9 patients with clinical T1c PCa were found to have tumor recurrence or metastasis and 5 patients had died caused by PCa. -

Continent Urostomy Guide

$POUJOFOU6SPTUPNZ(VJEF "QVCMJDBUJPOPGUIF6OJUFE0TUPNZ"TTPDJBUJPOTPG"NFSJDB *OD i4FJ[FUIF 0QQPSUVOJUZw CONTINENT UROSTOMY GUIDE Ilene Fleischer, MSN, RN, CWOCN, Author Patti Wise, BSN, RN, CWOCN, Author Reviewed by: Authors and Victoria A.Weaver, RN, MSN, CETN Revised 2009 by Barbara J. Hocevar, BSN,RN,CWOCN, Manager, ET/WOC Nursing, Cleveland Clinic © 1985 Ilene Fleischer and Patti Wise This guidebook is available for free, in electronic form, from United Ostomy Associations of America (UOAA). UOAA may be contacted at: www.ostomy.org • [email protected] • 800-826-0826 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 3 WHAT IS A CONTINENT UROSTOMY? . 4 THE URINARY TRACT . 4 BEFORE THE SURGERY . .5 THE SURGERY . .5 THE STOMA . 7 AFTER THE SURGERY . 7 Irrigation of the catheter(s) 8 Care of the drainage receptacles 9 Care of the stoma 9 Other important information 10 ROUTINE CARE AT HOME . 10 Catheterization schedule 11 How to catheterize your pouch 11 Special considerations when catheterizing 11 Care of the catheter 12 Other routine care 12 HELPFUL HINTS . .13 SUPPLIES FOR YOUR CONTINENT UROSTOMY . 14 LIFE WITH YOUR CONTINENT UROSTOMY . 15 Clothing 15 Diet 15 Activity and exercise 15 Work 16 Travel 16 Telling others 17 Social relationships 17 Sexual relations and intimacy 17 RESOURCES . .19 GLOSSARY OF TERMS . 20 BIBLIOGRAPHY . .21 1 INTRODUCTION Many people have ostomies and lead full and active lives. Ostomy surgery is the main treatment for bypassing or replacing intestinal or urinary organs that have become diseased or dysfunctional. “Ostomy” means opening. It refers to a number of ways that bodily wastes are re-routed from your body. A urostomy specifi cally redirects urine. -

Bilateral Laparoscopic Nephroureterectomy with Open

enDourology Bilateral laparoscopic nephroureterectomy with open cystoprostatectomy for simultaneous upper urinary tract carcinoma tomasz szydełko1, Jarosław Kasprzak1, Wojciech apoznański2, tadeusz niezgoda1, Marcin Kosiński1, anna Kołodziej1, Janusz Dembowski1, romuald Zdrojowy1 1Department of Urology and Urological Oncology, Wrocław University of Medicine, Wrocław, Poland 2Department of Pediatric Surgery and Urology, Wrocław University of Medicine, Wrocław, Poland describe bilateral laparoscopic nephroureterectomy and retroperi- Key WorDs toneal lymphadenectomy combined with cystectomy performed bilateral upper urinary tract carcinoma because of bilateral tumors of the renal pelvices. » laparoscopic nephroureterectomy » cystectomy MaterIal anD MethoDs aBstraCt patient Synchronous bilateral urothelial tumors of the A 74-year-old man with a history of transurethral resection upper urinary tract are extremely rare and their (TUR) and intravesical immunotherapy (BCG maintenance scheme) treatment constitutes a real challenge for urolo- because of bladder tumor, which was determined to be transitional gists. Whereas low grade superficial tumors can be cell carcinoma (TCC), pT1 grade 3 presented with gross hematuria treated using endoscopic procedures, in the case of in May 2008. Intravesical immunotherapy had been completed in high grade, invasive or large volume tumors bilat- 2003 and since then the patient had not turned up for follow-up. eral radical nephroureterectomy with cystectomy is Cystoscopy with mapping biopsy performed at presentation did not considered the standard of care. The authors present reveal any tumor in the bladder. The diagnostic evaluation, i.e. ul- the case of large volume high grade tumors of the trasound and CT revealed large volume bilateral renal pelvis tumors renal pelvices in a patient with a history of super- (Fig. 1). -

Paulos Yohannes, MD Board Certified Urologist and Diplomate of the American Board of Urology

Paulos Yohannes, MD Board Certified Urologist and Diplomate of the American Board of Urology Paulos Yohannes, Dr. Yohannes is one of the pioneers M.D. received of robotic urologic surgery in the his medical United States. He performed the first degree from the robotic cystoprostatectomy for bladder University of cancer (2003), robotic intracorporeal Louisville, School ileal conduit urinary diversion (2004), of Medicine and robotic repair of retrocaval and then ureter (2004) in the United States. completed his general surgery He is a reviewer for numerous peer- and urology reviewed journals, book chapters, and residency training has proctored many surgeons around at the University of Kentucky, Albert B. the country on their first prostatectomy Chandler medical center and University and cystoprostatectomy surgical cases. of Louisville Hospital. He completed a fellowship in Endourology/Laparoscopy He has won numerous awards including from Long Island Jewish Medical Center academic essay competitions, the where he specialized in minimally William Brohm Award, Pfizer scholar in invasive endourologic and laparoscopic urology award, and Kentucky Urologic surgery for the management of stone Society Pyelogram Award. In addition, disease; testicular, bladder, kidney, he has received recognition by Vitals and prostate cancer; percutaneous for: The Compassionate Doctor management of urothelial cancer, Award, Castle Connolly Regional as well as reconstructive surgery of Top Doctor Award, On Time Doctor the upper and lower urinary tract. Award, Patients’ Choice Award, and Top Ten Doctors - State award. 11181 Health Park Blvd., Suite 1115, Naples, FL 34110 8340 Collier Blvd., Suite 207, Naples, FL 34114 1839 San Marco Road, Marco Island, FL 34145 Phone: (239) 597-4440 • Fax: (239) 597-4441 Website: www.encoreurology.com • Email: [email protected]. -

Spring 2020 Newsletter

DEPARTMENT OF UROLOGYNEWS Volume 4 | SPRING 2020 CHAIR Benjamin R Lee, MD (interim) FACULTY Juan Chipollini, MD Joel Funk, MD Matthew Gretzer, MD David Tzou, MD Roger Nellans, MD Christian Twiss, MD Deb Jur, FNP Rosa Garcia, FNP Alison Grabowski, FNP Carmen Panizo, FNP Cara Whittingham, FNP RESEARCH Ken Batai, PhD Ava Wong, Coordinator AFFILIATED FACULTY Michael Siroky, MD Maximiliano Sorbellini, MD Mark Cogburn, MD Alex Jule, MD Rajesh Prasad, MD Jonathan Walker, MD Philip Gleason, MD Barry Chang, MD Hiep Nguyen, MD , Ariella Friedman, MD ADAPTABILITY Tamis Thrasher, PNP SOCIAL DISTANCING AND Department of Urology is published annually yearly by the University of Arizona College of Medicine Department of Urology. CRISIS MANAGEMENT CONTACT: Dr. Benjamin R. Lee, MD Chair (Interim) & Professor [email protected] Department of Urology The George W. Drach, MD Endowed Chair Department of Urology College of Medicine, Room 5325 The University of Arizona 1501 N. Campbell Ave. P.O. Box 245077 Tucson, AZ 85724-5077 520-694-4032 Fax: 520-694-5509 urology.arizona.edu All contents © 2020 Arizona Board of Regents. All rights reserved. The UA is an EEO/AA – M/W/D/V Employer. Design: UAHS BioCommunications To read this and past issues of Department of Urology Newsletter online, visit urology.arizona.edu/news-0 Deb Jur, NP Our Newest Nurse Practitioner Banner – University Medical Center Tucson welcomes Deb Jur, FNP to the Urology clinic at 3838 N Campbell Ave. Deb has been enthusiastically providing nursing care for her entire career, and has been an NP Dr. George W. Drach, Dr. Benjamin R Lee, Dean Michael Abecassis at the Investiture Ceremony specializing in urology for for the 1st Endowed Chair of Urology over 10 years. -

RAJ S. PRUTHI MD, FACS Curriculum Vitae

RAJ S. PRUTHI MD, FACS Curriculum Vitae Education 1994-98 Stanford University, Stanford, California Residency, Urology 1995-96 Stanford University, Stanford, California Fellow, Prostate cancer and ultrasonography, Dept. of Urology 1993-94 Stanford University, Stanford, California Residency, General Surgery 1992-93 Stanford University, Stanford, California Internship, General Surgery 1988-92 Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina M.D., May, 1992 1984-88 Stanford University, Stanford, California B.S. in Biology and B.A. in Economics with Honors, June, 1988 Board Certification/Licensure American Board of Urology 2002, recertification 2009 Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners 1999 North Carolina Medical Board 1998 Drug Enforcement Agency 1993 Professional Experience 5/2011 – present Division of Urology, UNC School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC Division Chief, Professor of Surgery 01/2011-05/2011 Division of Urology, UNC School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC Division Chief, Associate Professor of Surgery 5/2006 – 01/2011 Division of Urology, UNC School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC Associate Professor of Surgery (tenure) 4/2000 – 5/2006 Division of Urology, UNC School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC Assistant Professor of Surgery 4/1999 – 4/2000 Dept. of Urology, LSU Medical Center, Shreveport, Louisiana Assistant Professor of Urology 8/1998 – 4/1999 Kinston Urological Associates, Kinston, North Carolina Private Practice of Urology 1 Honors/Awards Faculty Teaching Award (“Attending of the Year), Division of Urologic Surgery, -

NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures

NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures 87:2009 Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP), version 1.14 Organization in charge of NCSP maintenance and updating: Nordic Centre for Classifications in Health Care WHO Collaborating Centre for the Family of International Classifications in the Nordic Countries Norwegian Directorate of Health PO Box 700 St. Olavs plass 0130 Oslo, Norway Phone: +47 24 16 31 50 Fax: +47 24 16 30 16 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.nordclass.org Centre staff responsible for NCSP maintenance and updating: Arnt Ole Ree, Centre Head Glen Thorsen, Trine Fresvig, Expert Advisers on NCSP Nordic Reference Group for Classification Matters: Denmark: Søren Bang, Ole B. Larsen, Solvejg Bang, Danish National Board of Health Finland: Jorma Komulainen, Matti Mäkelä, National Institute for Health and Welfare Iceland: Lilja Sigrun Jonsdottir, Directorate of Health, Statistics Iceland Norway: Øystein Hebnes, Trine Fresvig, Glen Thorsen, KITH, Norwegian Centre for Informatics in Health and Social Care Sweden: Lars Berg, Gunnar Henriksson, Olafr Steinum, Annika Näslund, National Board of Health and Welfare Nordic Centre: Arnt Ole Ree, Lars Age Johansson, Olafr Steinum, Glen Thorsen, Trine Fresvig © Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) 2009 Islands Brygge 67, DK-2300 Copenhagen Ø Phone: +45 72 22 76 25 Fax: +45 32 95 54 70 E-mail: [email protected] Cover by: Sistersbrandts Designstue, Copenhagen Printed by: AN:sats - Tryk & Design a-s, Copenhagen 2008 ISBN 978-87-89702-69-8 PREFACE Preface to NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures Version 1.14 The Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) published the first printed edition of the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP) in 1996. -

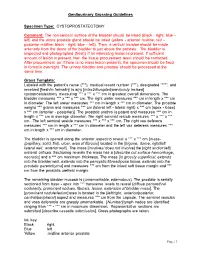

Genitourinary Grossing Guidelines Specimen Type

Genitourinary Grossing Guidelines Specimen Type: CYSTOPROSTATECTOMY Comment: The non-serosal surface of the bladder should be inked (black - right; blue – left) and the entire prostate gland should be inked (yellow - anterior midline; red – posterior midline; black - right; blue – left). Then, a vertical incision should be made anteriorly from the dome of the bladder to just above the prostate. The bladder is inspected and photographed (fresh) if an interesting lesion is present. If sufficient amount of lesion is present, then the tissue procurement team should be contacted. After procurement (or if there is no mass lesion present), the specimen should be fixed in formalin overnight .The urinary bladder and prostate should be processed at the same time. Gross Template: Labeled with the patient’s name (***), medical record number (***), designated “***”, and received [fresh/in formalin] is a(n) [intact/disrupted/previously incised] cystoprostatectomy measuring *** x *** x *** cm in greatest overall dimensions. The bladder measures *** x *** x *** cm. The right ureter measures *** cm in length x *** cm in diameter. The left ureter measures *** cm in length x *** cm in diameter. The prostate weighs *** grams and measures *** cm (lateral left - lateral right) x *** cm (apex - base) x *** cm (anterior - posterior)]. The prostatic urethra is patent and measures *** cm in length x *** cm in average diameter. The right seminal vesicle measures *** x *** x *** cm . The left seminal vesicle measures *** x *** x *** cm. The right vas deferens measures *** cm in length x *** cm in diameter and the left vas deferens measures *** cm in length x *** cm in diameter. The bladder is opened along the anterior aspect to reveal a *** x *** cm [mass- (papillary, solid, flat), ulcer, area of fibrosis] located in the [trigone, dome, right/left lateral wall, anterior wall]. -

Original Research Article

International Surgery Journal Agarwal S et al. Int Surg J. 2018 Sep;5(9):3038-3042 http://www.ijsurgery.com pISSN 2349-3305 | eISSN 2349-2902 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2349-2902.isj20183719 Original Research Article Indications and outcome of patients undergoing cutaneous ureterostomy as a mode of urinary diversion after radical cystectomy: an experience from a tertiary care center Shikhar Agarwal, Rajeev Sarpal*, Shivam Dang, Yogesh Kalra, Manoj Biswas Department of General Surgery, Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences, SRHU, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India Received: 11 July 2018 Accepted: 06 August 2018 *Correspondence: Dr. Rajeev Sarpal, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Background: Radical cystectomy is associated with high morbidity, especially in elderly patients. Most of the associated complications are related to the urinary diversion. Cutaneous ureterostomy (CU) is usually an uncommon form of urinary diversion and is avoided because of the frequent complication of stomal stenosis. Methods: In this study the authors retrospectively analyzed 84 patients who underwent radical cystectomy. 17 Patients who underwent single stoma CU were included in the study who required lifelong monthly stent changes. Varied indication and outcome of these patients were analyzed. Results: Patients in which CU was used as a mode of urinary diversion had less blood loss, less operative time and discharged without ICU stay. -

The Role of Cystoprostatectomy in Management of Locally Advanced

Yuan et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2020) 18:14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-1791-5 REVIEW Open Access The role of cystoprostatectomy in management of locally advanced prostate cancer: a systematic review Peng Yuan, Shen Wang, Xiao Liu, Xinguang Wang, Zhangqun Ye and Zhiqiang Chen* Abstract Background: The role of cystoprostatectomy for the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer (LAPC) was evaluated by a comprehensive review of contemporary literatures. Methods: A systematic search of English language literatures using PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane library, from 1990 to 2018, was performed. Two independent authors reviewed abstracts as well as full- text articles and extracted data from the selected manuscripts. Results: After the literature research, seven articles with a total of 211 patients were identified. Both 120 cases who received cystoprostatectomy for the primary treatment of LAPC and 91 cases for the salvage surgery after local recurrence were finally included. Overall incidence of positive surgical margins ranged from 25 to 78%. The incidence of major complications caused by the surgery during the follow-up time was limited. It had been reported that among LAPC patients who received cystoprostatectomy combined with adjuvant therapies, 5-year cancer-specific survival rate and 5-year biochemical progression-free survival was up to 87.1% and 62.2%. Moreover, symptoms such as hematuria and other urination dysfunctions, as well as patients’ quality of life were significantly improved after cystoprostatectomy in LAPC patients with the bladder invasion. Conclusions: Cystoprostatectomy can serve as an alternative to the surgical step of multimodal therapy for highly selected LAPC patients with the bladder invasion, which may improve patients’ symptoms and related quality of life. -

Immunohistochemical Evaluation of the Safety of Transurethral Electrovaporization of the Prostate and Its Clinical Results

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (1999) 2, 16±20 ß 1999 Stockton Press All rights reserved 1365±7852/99 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/pc Immunohistochemical evaluation of the safety of transurethral electrovaporization of the prostate and its clinical results A Tizzani1, P Gontero*3, G Casetta1, P Piana1, C Baima1, A de Zan1, G Bodo1 and D Pacchioni2 Departments of 1Pathologic Urology and 2Pathology, University of Torino, Torino, Italy; and 3Department of Urology, King's College Hospital, London, UK Short term follow up studies on transurethral electrovaporization (TUEVP) have shown a relative low morbidity over TURP. The use of high power current has been claimed as a source of possible damage on the neuronal structures surrounding the prostate. The aims of our study were to assess longer follow up results as well as the safety of this technique. Over an 18 month mean follow up period symptom relief remained relatively stable. Postoperative dysuria was detected in a higher percentage of patients and was seen for a longer period in comparison with previous reports. Immunohistochemical staining performed using S-100 and NF monoclonal antibodies showed anatomical integrity of the prostatic neuronal ®bres sur- rounding the vaporization edge. In conclusion, although the effectiveness and safety of TUEVP are con®rmed by the present study, the occurrence of a signi®cant rate of long-lasting post- operative irritative symptoms must be taken into account. Keywords: prostate electrovaporization; side effects; safety; neuronal damage; -

LAPAROSCOPIC ASSISTED RADICAL CYSTOPROSTATECTOMY International Braz J Urol Vol

Surgical TechniqueLAPAROSCOPIC ASSISTED RADICAL CYSTOPROSTATECTOMY International Braz J Urol Vol. 31 (4): 362-369, July - August, 2005 Official Journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology LAPAROSCOPIC ASSISTED RADICAL CYSTOPROSTATECTOMY WITH Y-SHAPED ORTHOTOPIC ILEAL NEOBLADDER CONSTRUCTED WITH NON-ABSORBABLE TITANIUM STAPLES THROUGH A 5 CM PFANNENSTEIL INCISION SIDNEY C. ABREU, FREDERICO I. MESSIAS, RENATO S. ARGOLLO, GLAUCO A. GUEDES, MARDHEN B. ARAUJO, GILVAN N. FONSECA Urological Hospital of Brasília (SCA, FIM, RSA, GAG) and Sections of Urology, Federal University of Ceara (MBA) and Federal University of Goias (GNF), Brazil ABSTRACT Introduction: We performed a laparoscopic radical cystoprostatectomy followed by con- structing a Y-shaped reservoir extra-corporeally with titanium staples through a 5-cm muscle-splitting Pfannenstiel incision. Surgical technique: Upon completion of the extirpative part of the operation, the surgical specimen was entrapped and removed intact through a 5-cm Pfannenstiel incision. Through the ex- traction incision, the distal ileum was identified and a 40 cm segment isolated. With the aid of the laparoscope, the ureters were brought outside the abdominal cavity and freshened and spatulated for approximately 1.5-cm. Bilateral double J ureteral stents were then inserted up to the renal pelvis and the ureters were directly anastomosed to the open ends of the limbs of the neobladder. Following this, the isolated intestinal segment was arranged in a Y shape with two central segments of 14 cm and two limbs of 6 cm. The two central segments were brought together and detubularized, with two sequen- tial firings of 80 x 3.5 mm and 60 x 3.5 mm non-absorbable mechanical stapler (Multifire GIA - US Surgical) inserted through an opening made at the lowest point of the neobladder on its anti-mesen- teric border.