Introduction 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recovering and Rendering Vital Blueprint for Counter Education At

Recovering and Rendering Vital clash that erupted between the staid, conservative Board of Trustees and the raucous experimental work and atti- Blueprint for Counter Education tudes put forth by students and faculty (the latter often- times more militant than the former). The full story of the at the California Institute of the Arts Institute during its frst few years requires (and deserves) an entire book,8 but lines from a 1970 letter by Maurice Paul Cronin Stein, founding Dean of the School of Critical Studies, written a few months before the frst students arrived on campus, gives an indication of the conficts and delecta- tions to come: “This is the most hectic place in the world at the moment and promises to become even more so. At heart of the California Institute of Arts’ campus is We seem to be testing some complex soap opera prop- a vast, monolithic concrete building, containing more osition about the durability of a marriage between the than a thousand rooms. Constructed on a sixty-acre site radical right and left liberals. My only way of adjusting to thirty-fve miles north of Los Angeles, it is centered in the situation is to shut my eyes, do my job, and hope for what at the end of the 1960s was the remote outpost the best.”9 of sun-scorched Valencia (a town “dreamed up by real estate developers to receive the urban sprawl which is • • • Los Angeles”),1 far from Hollywood, a town that was—for many students at the Institute—the belly of the beast. -

The Beckett Collection Ruby Cohn Correspondence 1959-1989

The Beckett Collection Ruby Cohn correspondence 1959-1989 Summary description Held at: Beckett International Foundation, University of Reading Title: The Correspondence of Ruby Cohn Dates of creation: 1959 – 1989 Reference: Beckett Collection--Correspondence/COH Extent: 205 letters and postcards from Samuel Beckett to Ruby Cohn 1 telex message from Beckett to Cohn 1 telegram from Beckett to Cohn 1 postcard addressed to Georges Cravenne 5 letters from Cohn to Beckett (which include Beckett’s responses) 1 envelope containing a typescript of third section of Stirrings Still 2 empty envelopes addressed to Cohn Language of material English unless otherwise stated Administrative information Immediate source of acquisition The correspondence was donated to the Beckett International Foundation by Ruby Cohn in 2002. Copyright/Reproduction Permission to quote from, or reproduce, material from this correspondence collection is required from the Samuel Beckett Estate before publication. Preferred Citation Preferred citation: Correspondence of Samuel Beckett and Ruby Cohn, Beckett International Foundation, Reading University Library (RUL MS 5100) Access conditions Photocopies of the original materials are available for use in the Reading Room. Access to the original letters is restricted. Historical Note 1922, 13 Aug. Born Ruby Burman in Columbus, Ohio 1942 Awarded a BA degree from Hunter College of the City of New York 1946 Married Melvin Cohn (they divorced in 1961) 1952 Awarded a doctorate from the University of Paris 1960 Awarded a second doctorate from Washington University (Saint Louis, Mo.) 1961-1968 Professor of English and Comparative Literature at San Francisco State University 1969-1971 Fellow at the California Institute of the Arts 1972-1992 Professor of Comparative Drama at the University of California, Davis 1992-Present Professor Emerita of Comparative Drama at the University of California, Davis Ruby Cohn (née Burman) was born on 13 August 1922 in Columbus, Ohio, where her father, Peter Burman, was a veterinary student. -

Artists' Books : a Critical Anthology and Sourcebook

Anno 1778 PHILLIPS ACADEMY OLIVER-WENDELL-HOLMES % LI B R ARY 3 #...A _ 3 i^per ampUcm ^ -A ag alticrxi ' JZ ^ # # # # >%> * j Gift of Mark Rudkin Artists' Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook ARTISTS’ A Critical Anthology Edited by Joan Lyons Gibbs M. Smith, Inc. Peregrine Smith Books BOOKS and Sourcebook in association with Visual Studies Workshop Press n Grateful acknowledgement is made to the publications in which the following essays first appeared: “Book Art,” by Richard Kostelanetz, reprinted, revised from Wordsand, RfC Editions, 1978; “The New Art of Making Books,” by Ulises Carrion, in Second Thoughts, Amsterdam: VOID Distributors, 1980; “The Artist’s Book Goes Public,” by Lucy R. Lippard, in Art in America 65, no. 1 (January-February 1977); “The Page as Al¬ ternative Space: 1950 to 1969,” by Barbara Moore and Jon Hendricks, in Flue, New York: Franklin Furnace (December 1980), as an adjunct to an exhibition of the same name; “The Book Stripped Bare,” by Susi R. Bloch, in The Book Stripped Bare, Hempstead, New York: The Emily Lowe Gallery and the Hofstra University Library, 1973, catalogue to an exhibition of books from the Arthur Cohen and Elaine Lustig col¬ lection supplemented by the collection of the Hofstra Fine Arts Library. Copyright © Visual Studies Workshop, 1985. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except in the case of brief quotations in reviews and critical articles, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Boulos, Daniel

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fortresses of Culture: Cold War Mobilization, Urban Renewal, and Institutional Identity in the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center and Center Theatre Group Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8n50d91d Author Boulos, Daniel Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Fortresses of Culture: Cold War Mobilization, Urban Renewal, and Institutional Identity in the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center and Center Theatre Group A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater Studies by Daniel Boulos Committee in charge: Professor W. Davies King, Chair Professor Leo Cabranes-Grant Professor Simon Williams June 2018 The dissertation of Daniel Boulos is approved. _____________________________________________ Leo Cabranes-Grant _____________________________________________ Simon Williams _____________________________________________ W. Davies King, Committee Chair March 2018 Fortresses of Culture: Cold War Mobilization, Urban Renewal, and Institutional Identity in the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center and Center Theatre Group Copyright © 2018 by Daniel Boulos iii VITA OF DANIEL BOULOS EDUCATION Bachelor of Fine Arts in Theater, Montclair State University, May 1997 Master of Arts in Theater History and Criticism, Brooklyn College, June 2012 Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre -

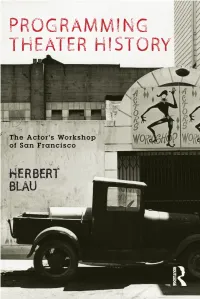

Programming Theater History

Programming Theater History “One of the great stories of the American theater..., The Workshop not only built an international reputation with its daring choice of plays and non-traditional productions, it also helped launch a movement of regional, or resident, companies that would change forever how Americans thought about and consumed theater.” (Elin Diamond, from the Introduction.) Herbert Blau founded, with Jules Irving, the legendary Actor’s Workshop of San Francisco, in 1952, starting with ten people in a loft above a judo academy. Over the course of the next thirteen years and its hundred or so productions, it introduced American audiences to plays by Brecht, Beckett, Pinter, Genet, Arden, Fornes, and various unknown others. Most of the productions were accompanied by a stunningly concise and often provocative program note by Blau. These documents now comprise, within their compelling perspective, a critique of the modern theater. They vividly reveal what these now canonical works could mean, fi rst time round, and in the context of 1950s and 1960s American culture, in the shadow of the Cold War. Programming Theater History curates these notes, with a selection of The Workshop’s incrementally artful, alluring program covers, Blau’s recollections, and evocative production photographs, into a narrative of indispensable artefacts and observations. The result is an inspiring testimony by a giant of American performance theory and practice, and a unique refl ection of what it is to create theatre history in the present. Herbert Blau is Byron W. and Alice L. Lockwood Professor Emeritus of the Humanities at the University of Washington, USA. -

HERBERT BLAU Degrees: Ph.D. 1954 Stanford University

HERBERT BLAU Degrees: Ph.D. 1954 Stanford University (English/American Literature) M.A. 1949 Stanford University (Speech and Drama) B.Ch.E. 1947 New York University (Chemical Engineering) Academic Experience 2000- Byron W. and Alice L. Lockwood Professor in the Humanities (English and Comparative Literature) and Adjunct Professor in School of Drama, University of Washington 1984-00 Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature, University of Wisconsin--Milwaukee 1978-84 Professor of English, University of Wisconsin--Milwaukee 1974-78 Dean, Division of Arts and Humanities, and Professor of English, University of Maryland--Baltimore Co. 1972-74 Professor of the Arts (College and Conservatory) and Director of Inter-Arts Program, Oberlin College 1968-71 Founding Provost, and Dean of the School of Theater and Dance, California Institute of the Arts 1967-68 Professor of English, City College of the City University of New York 1950-65 Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor of English and World Literature, San Francisco State University Theater Experience 1971-81 Founder and Artistic Director, KRAKEN 1965-67 Co-Director, Repertory Theater of Lincoln Center, New York 1952-65 Co-Founder and Co-Director, The Actor's Workshop of San Francisco Other Academic Appointments 2006 Research Seminar, Institute for Theater Studies, Berlin 1995 Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Copenhagen, Denmark 1993 Visiting Professor, University of Mainz, Germany 1984 Visiting Professor, University of the Bosphorus, Turkey -

The Faith-Based Initiative of the Theater of the Absurd Herbert Blau

Fall 2001 3 The Faith-Based Initiative of the Theater of the Absurd Herbert Blau Some prefatory words, or what, in more classical times, might have been called an apology. In the invitation to this symposium,1 the topic proposed for me was "The Raging Soul of the Absurd." I don't know whether that came out of some tongue-in-cheek take on my temperament derived from the rather reticent things I've written, but as it turns out, though I've used another title, I will be saying something of the soul, not exactly raging, in another context. There was also a warning with the invitation—and I hope to be forgiven for saying so—that the audience here was not likely to "consist of specialists or academics per se," but rather a group of that "dying breed, the 'educated public,' which means we need to keep vocabulary relatively jargon free and inclusive." As it happens, that gave me the idea for what I have written about, while feeling somewhat like Jack, in Jack or the Submission, when he's told he's "chronometrable"—meaning, perhaps, it's time for him to change—after exclaiming, "Oh words, what crimes are committed in your name!" This leads to his agreeing to "abide by the circumstances,... the game of the rule," acceding to the familiar, "Oh well, yes, yes, na, I adore hashed brown potatoes."2 Which, actually, I try to avoid, though that may not keep me, with respect for the game of the rule, from making a hash of words, or to use a word coming up later, an "assemblage." Chronometrably, I might even wish that Roberta II—Jack's fiancee with three noses—were right and all we'd need "to designate things is one single word: cat," the word chat, of course, used as a prefix, sexier in French, though "The cat's got my tongue," able thus to accommodate all propositions. -

Essential Ruptures Herbert Blau’S Power of Mind

Essential Ruptures Herbert Blau’s Power of Mind Joseph Cermatori rom the 1950s until today, some six years after his death, Herbert Blau has been regarded as one of the United States’ most significant theatre intel- F lectuals. That rare combination of theorist, educator, and artist, his career spanned more than six decades, twelve books, three performance companies, numerous distinguished academic appointments, and countless students and collaborators. As a stage director, he introduced American audiences to Samuel Beckett, Bertolt Brecht, and Jean Genet. His San Francisco Actor’s Workshop production of Waiting for Godot, at San Quentin State Prison, launched him to widespread attention by appearing prominently in the introduction to Martin Esslin’s Theatre of the Absurd. During the 1960s, he called for a desublimated future free from state repressive violence: the marriage of socialism and surrealism. He denounced the commercial American theatre and proposed its decentralization in his influential book The Impossible Theatre. Later, as co-artistic director (with Jules Irving) of the Lincoln Center Repertory Theatre, he stuck his finger in the eye of New York’s banker class with a production of Danton’s Death, tailor-made to outrage his patrons. Drummed out of town, he founded innovative training programs at CalArts and Oberlin and nurtured the careers of Allan Kaprow, Nam June Paik, and María Irene Fornés, to name just three. When European poststruc- turalism arrived in North America during the 1970s, it entered theatre (and later performance) studies largely through Blau’s intervention. It risks understatement to say that his life was one of enormous creative fecundity. -

Pauline Oliveros Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86w9d7v Online items available Pauline Oliveros Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2013 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Pauline Oliveros Papers MSS 0102 1 Descriptive Summary Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Pauline Oliveros Papers Creator: Oliveros, Pauline, 1932-2016 Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0102 Physical Description: 20.4 Linear feet(31 archives boxes, 7 flat boxes, 2 map case folders, and 2 card file boxes) Date (inclusive): 1931-1981 Abstract: Papers of Pauline Oliveros (1932-2016), American experimental musician, composer and key figure in the development of contemporary electronic music. The collection contains Oliveros' original writings, compositions, correspondence and sketches. Also included are interviews, programs and reviews, teaching materials and writings about and relating to Oliveros' work. Languages: English . Restrictions Original media formats are restricted. Viewing/listening copies may be available for researchers. Acquisition Information Acquired 1981-1996. Preferred Citation Pauline Oliveros Papers, MSS 102. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. Scope and Content of Collection Papers of Pauline Oliveros, composer, accordionist and former music professor at UCSD. Materials include correspondence, works and writings by Pauline Oliveros and others, manuscripts of Oliveros' compositions, subject files, reel-to-reel audio tapes and ephemera. These materials were originally located at UCSD's Music Library. Arranged in eleven series: 1) WORKS BY PAULINE OLIVEROS, 2) WRITINGS, 3) PROJECTS, 4) INTERVIEWS AND CRITICISMS, 5) PROGRAMS AND REVIEWS, 6) UNIVERSITY MATERIALS, 7) WORKS BY OTHERS, 8) WRITINGS BY OTHERS, 9) CORRESPONDENCE, 10) BIOGRAPHICAL and 11) ELECTRONIC MUSIC SYSTEMS. -

Oral History Project

ORAL HISTORY PROJECT MADE POSSIBLE BY SUPPORT FROM PROJECT PARTNERS: The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts INTERVIEW SUBJECT: Michael Scroggins Biography: Michael Scroggins was one of the founding members of Single Wing Turquoise Bird, a successful Los Angeles-based psychedelic light show. Scroggins grew up in the Valley and attended Canoga Park High. During the 1960s he began spending time in Topanga Canyon with local artists including Wallace Berman. Videography: 1971 Damage 1972 Lose Yr Jobs 1972 1973 Countdown 1973 Meander 1977 King and Queen 1973 Resolution Michael Scroggins Oral History Transcript/Los Angeles Filmforum Page 1 of 200 1973 Padma 1973 Tucker 1974 Exchange 1974 Dog Plea 1974 For Sam 1974 Corrigan/Lund 1975 Sangsara 1975 Scraps 1977 Rockabye 1979 Drone 1979 Destiny Edit 1980 Recent Li 1982 Nuvudeo 1982 Saturnus Alchimia 1983 Study No. 1 1983 Study No. 9 1983 Study No. 2 1983 Study No. 5 1983 Study No. 6 1983 Study No. 7 1983 Study No. 11 1983 Study No. 13 1983 Study No. 14 1983 Study No. 16 1986 Power Spot 1986 Solaire 1986 California Dream 1989 1921 > 1989 2006 Momentarily (work-in-progress) 2007 what are you looking at? (edit from 1971/1973 recordings) 2009 Adagio for Jon and Helena 2010 Limn 2010 Out of Our Depths (ensemble performance recording, SWTB) 2011 Untitled (ensemble performance recording, SWTB) Performance and Installation Work: 1988 Talos et Koine (live video processing for Michel Redolfi concert, Nice) 1992 Mata Pau (video performance for Michel Redolfi concert, Metz) 1994 Topological Slide (VR -

By Alison Knowles

THE JAMES GALLERY — THE GRADUATE CENTER , CUNY SEP 8 – Oct 29, 2016 — E XHIBITION, TEX TS A ND PRog RAMS BY ALISON KNOWLES 36 5 FIftH AV ENUE AT 35TH StREET — THE GRADUATE CENTER , CUNY CENTERFORTHEHUMANITIES.ORG/JAMES-GALLERY PROPOSED BY ART BY T R A NSL A T I O N ( I NTERN A TION A L R E S E A R C H P R O G R A M I N A R T A N D C U R A TORI A L P R A CTICES) ALISON KNOWLES AND AY-O, CHLOË BASS, KEREN BENBENISTY, JÉRÉMIE BENNEQUIN, GEORGE BRECHT, HUgo BRÉGEAU, MARCEL BRooDTHAERS, JOHN CAGE, ALEJANDRO CESARco, JAGNA CIUCHTA, CONSTANT, YoNA FRIEDMAN, MARK GEffRIAUD, BEATRICE GIBSON, EUGEN GOMRINGER, DAN GRAHAM, JEff GUESS, GEoffREY HENDRIckS, DIck HIggINS, TOSHI IcHIYANAGI, NoRMAN C. KAPLAN, ALLAN KAPROW, FREDERIck KIESLER, NICHOLAS KNIGHT, KATARZYNA KRAkoWIAK, MIkko KUORINKI, THEO LUTZ, StEPHANE MALLARMÉ, ALAN MICHELSON, Yoko ONO, NAM JUNE PAIK, JENNY PERLIN, NINA SAFAINIA, CAROLEE ScHNEEMANN, MIEko SHIOMI, JAMES TENNEY, SRDJAN JOVANOVIC WEISS, EMMEtt WILLIAMS. — CURAtoRS: KATHERINE CARL, MAUD JACQUIN AND SÉBASTIEN PLUot WED, SEP 7, 6–8PM EXHIBITION RECEPTION Alison Knowles’s computerized poem of 1967, The House of Dust, her subsequent built struc- tures of the same name, and the many works it generated are the focus of this presentation. Documentation of Knowles’s poem and built structures, discussions, publications, and per- formances are presented in dialogue with other artworks from the period—predominantly by Knowles and other Fluxus artists—exploring the nexus of art, technology and architecture in ways that resonate with The House of Dust. -

The Commodius Vicus of Beckett

Spring 2004 The Commodius Vicus of Beckett: Vicissitudes of the Arts in the Science of Affliction* Herbert Blau "To think perhaps it won't all have been for nothing!" Hamm, in Endgame^ When the theater becomes conscious of itself as theater, it is not so much studying itself as an object but realizing that theatricality, if too elusive for objectification, materializes in thought, like representation for the human sciences, as a condition of possibility, which as always remains to be seen. Once that is realized, there is no alternative but for the theater to become more and more self- conscious, even beyond Brecht, reflexively critical, with the dispelling of illusion, however, as another order of illusion in which there will inevitably be a succession of démystifications and unveilings, but as if the teasers and tormentors that frame the stage (even in a thrust, or presumably open stage) were revealing nothing so much as the future of illusion. This might be thought of, too, in its materialization, and especially in Beckett, as the nothing that comes of nothing or, in despite of nothing—as he says of sounds, in "Variations on a 'Still' Point"—"mostly not for nothing never quite for nothing,"^ the inexhaustible stirrings still, at "the very heart of which no limit of any kind was to be discovered but always in some quarter or another some end in sight such as a fence or some manner of bourne from which to return" ("Stirrings Still" 263). Even if the return were guaranteed by the "preordained cyclicism" that Beckett perceived in Vico,^ this could, of course, "all Herbert Blau is the Byron W.