Past As Prologue: Dreams of an Ideal Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recovering and Rendering Vital Blueprint for Counter Education At

Recovering and Rendering Vital clash that erupted between the staid, conservative Board of Trustees and the raucous experimental work and atti- Blueprint for Counter Education tudes put forth by students and faculty (the latter often- times more militant than the former). The full story of the at the California Institute of the Arts Institute during its frst few years requires (and deserves) an entire book,8 but lines from a 1970 letter by Maurice Paul Cronin Stein, founding Dean of the School of Critical Studies, written a few months before the frst students arrived on campus, gives an indication of the conficts and delecta- tions to come: “This is the most hectic place in the world at the moment and promises to become even more so. At heart of the California Institute of Arts’ campus is We seem to be testing some complex soap opera prop- a vast, monolithic concrete building, containing more osition about the durability of a marriage between the than a thousand rooms. Constructed on a sixty-acre site radical right and left liberals. My only way of adjusting to thirty-fve miles north of Los Angeles, it is centered in the situation is to shut my eyes, do my job, and hope for what at the end of the 1960s was the remote outpost the best.”9 of sun-scorched Valencia (a town “dreamed up by real estate developers to receive the urban sprawl which is • • • Los Angeles”),1 far from Hollywood, a town that was—for many students at the Institute—the belly of the beast. -

University of Maine System Mail - Six Peaceful Picks to Say Hello, 2021

University of Maine System Mail - Six Peaceful Picks to say Hello, 2021 https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0?ik=483c7a7ff8&view=pt&search=all&... Matthew Revitt <[email protected]> Six Peaceful Picks to say Hello, 2021 1 message Collins Center for the Arts <[email protected]> Fri, Jan 8, 2021 at 8:00 AM To: "Matthew," <[email protected]> Be sure to check out this week's special bonus feature... Click to view in web browser Dear Matthew, Here are this week's Six Picks to keep you connected to the world of performing arts. Find more links like these on our website. Enjoy! What I Miss About The Shows Must Go On - David Bowie's Lazarus Broadway, by Marsha Featuring Michael Ball Jan. 8 & 9, 9 p.m., Jan. 10, 4 Mason Jan. 8, 2 p.m. for 48 hours p.m. Jan. 2 & 3 Relive Michael Ball's sold-out Watch the London production of In an exclusive interview with Heroes Tour, featuring solid gold, David Bowie’s ‘Lazarus,’ filmed TheaterMania, Marsha Mason, classic songs which were live onstage in 2016. The the four-time Oscar nominee and originally big hits for legendary musical, which weaves together veteran stage actor/director, artists such as Tony Bennett, music from the iconic singer’s describes what she misses most Johnny Mathis, Frank Sinatra, lengthy and diverse catalog, will about working in the theater Neil Diamond, Billy Joel, Tom be live streamed for the first time during this period of extended Jones and more. Hear hits some to mark both the late singer's closure. -

ATHE's 24Th Annual Conference August 3-6, 2010 Hyatt Regency

ATHE’s 24th Annual Conference August 3-6, 2010 Hyatt Regency Century Plaza Hotel, Los Angeles, CA | | ATHE’s 24th Annual Conference August 3-6, 2010 Hyatt Regency Century Plaza Hotel Los Angeles, CAlifornia Welcome to You are one of over 800 ATHE members, presenters, and guest artists who are gathered for the 24th annual Association for Theatre in Higher Education conference. “Theatre Alive:This Theatre, time we will dialogue Media, about theatre and and the Survival!”professoriate in the rapidly chang- ing 21st century, especially in light of developments in media, career preparation and professional development, and our roles in the redefinition of higher education. What more fitting sense of place for a conference examining possibilities and chal- lenges at the intersections of higher education, theatre and media than the City of Angeles. LA is a land of dreams and opportunities--the Entertainment Capital of the World--and a city of changing circumstances that also resonate where we all live and work. Congratulations to this year’s outstanding Conference Committee for crafting a per- fect sequel to last year’s conference, Risking Innovation. What are the emerging best practices that engage media in pedagogy, curricular design, and scholarship culmi- nating in publication or creative production? Pre-conference and conference events that explore this question are packed into four intense days. Highlights include: • Pulitzer Prize-winning Playwright Susan Lori-Parks’ Keynote Address • Opening Reception in the Exhibition Hall • THURGOOD with Laurence Fishburne • All-Conference Forum, “Elephants in the Curriculum: A Frank Discussion about Theatre in a Changing • Academic Landscape” • 12 Exciting Focus Group Debut Panels • Innovative multidisciplinary presentations • ATHE Awards Ceremony • ATHE Annual Membership Meeting • MicroFringe Festival • Professional Workshops with Arthur Lessac, Aquila Theatre’s Peter Meineck, Teatro Punto’s Carlos Garcia Estevez and Katrien van Beurden, arts activist Caridad Svich, and UCLA performance artist and composer Dan Froot. -

The Beckett Collection Ruby Cohn Correspondence 1959-1989

The Beckett Collection Ruby Cohn correspondence 1959-1989 Summary description Held at: Beckett International Foundation, University of Reading Title: The Correspondence of Ruby Cohn Dates of creation: 1959 – 1989 Reference: Beckett Collection--Correspondence/COH Extent: 205 letters and postcards from Samuel Beckett to Ruby Cohn 1 telex message from Beckett to Cohn 1 telegram from Beckett to Cohn 1 postcard addressed to Georges Cravenne 5 letters from Cohn to Beckett (which include Beckett’s responses) 1 envelope containing a typescript of third section of Stirrings Still 2 empty envelopes addressed to Cohn Language of material English unless otherwise stated Administrative information Immediate source of acquisition The correspondence was donated to the Beckett International Foundation by Ruby Cohn in 2002. Copyright/Reproduction Permission to quote from, or reproduce, material from this correspondence collection is required from the Samuel Beckett Estate before publication. Preferred Citation Preferred citation: Correspondence of Samuel Beckett and Ruby Cohn, Beckett International Foundation, Reading University Library (RUL MS 5100) Access conditions Photocopies of the original materials are available for use in the Reading Room. Access to the original letters is restricted. Historical Note 1922, 13 Aug. Born Ruby Burman in Columbus, Ohio 1942 Awarded a BA degree from Hunter College of the City of New York 1946 Married Melvin Cohn (they divorced in 1961) 1952 Awarded a doctorate from the University of Paris 1960 Awarded a second doctorate from Washington University (Saint Louis, Mo.) 1961-1968 Professor of English and Comparative Literature at San Francisco State University 1969-1971 Fellow at the California Institute of the Arts 1972-1992 Professor of Comparative Drama at the University of California, Davis 1992-Present Professor Emerita of Comparative Drama at the University of California, Davis Ruby Cohn (née Burman) was born on 13 August 1922 in Columbus, Ohio, where her father, Peter Burman, was a veterinary student. -

Artists' Books : a Critical Anthology and Sourcebook

Anno 1778 PHILLIPS ACADEMY OLIVER-WENDELL-HOLMES % LI B R ARY 3 #...A _ 3 i^per ampUcm ^ -A ag alticrxi ' JZ ^ # # # # >%> * j Gift of Mark Rudkin Artists' Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook ARTISTS’ A Critical Anthology Edited by Joan Lyons Gibbs M. Smith, Inc. Peregrine Smith Books BOOKS and Sourcebook in association with Visual Studies Workshop Press n Grateful acknowledgement is made to the publications in which the following essays first appeared: “Book Art,” by Richard Kostelanetz, reprinted, revised from Wordsand, RfC Editions, 1978; “The New Art of Making Books,” by Ulises Carrion, in Second Thoughts, Amsterdam: VOID Distributors, 1980; “The Artist’s Book Goes Public,” by Lucy R. Lippard, in Art in America 65, no. 1 (January-February 1977); “The Page as Al¬ ternative Space: 1950 to 1969,” by Barbara Moore and Jon Hendricks, in Flue, New York: Franklin Furnace (December 1980), as an adjunct to an exhibition of the same name; “The Book Stripped Bare,” by Susi R. Bloch, in The Book Stripped Bare, Hempstead, New York: The Emily Lowe Gallery and the Hofstra University Library, 1973, catalogue to an exhibition of books from the Arthur Cohen and Elaine Lustig col¬ lection supplemented by the collection of the Hofstra Fine Arts Library. Copyright © Visual Studies Workshop, 1985. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except in the case of brief quotations in reviews and critical articles, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Boulos, Daniel

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fortresses of Culture: Cold War Mobilization, Urban Renewal, and Institutional Identity in the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center and Center Theatre Group Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8n50d91d Author Boulos, Daniel Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Fortresses of Culture: Cold War Mobilization, Urban Renewal, and Institutional Identity in the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center and Center Theatre Group A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater Studies by Daniel Boulos Committee in charge: Professor W. Davies King, Chair Professor Leo Cabranes-Grant Professor Simon Williams June 2018 The dissertation of Daniel Boulos is approved. _____________________________________________ Leo Cabranes-Grant _____________________________________________ Simon Williams _____________________________________________ W. Davies King, Committee Chair March 2018 Fortresses of Culture: Cold War Mobilization, Urban Renewal, and Institutional Identity in the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center and Center Theatre Group Copyright © 2018 by Daniel Boulos iii VITA OF DANIEL BOULOS EDUCATION Bachelor of Fine Arts in Theater, Montclair State University, May 1997 Master of Arts in Theater History and Criticism, Brooklyn College, June 2012 Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre -

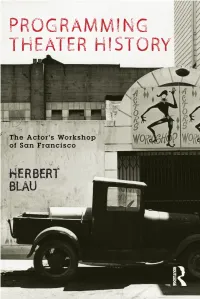

Programming Theater History

Programming Theater History “One of the great stories of the American theater..., The Workshop not only built an international reputation with its daring choice of plays and non-traditional productions, it also helped launch a movement of regional, or resident, companies that would change forever how Americans thought about and consumed theater.” (Elin Diamond, from the Introduction.) Herbert Blau founded, with Jules Irving, the legendary Actor’s Workshop of San Francisco, in 1952, starting with ten people in a loft above a judo academy. Over the course of the next thirteen years and its hundred or so productions, it introduced American audiences to plays by Brecht, Beckett, Pinter, Genet, Arden, Fornes, and various unknown others. Most of the productions were accompanied by a stunningly concise and often provocative program note by Blau. These documents now comprise, within their compelling perspective, a critique of the modern theater. They vividly reveal what these now canonical works could mean, fi rst time round, and in the context of 1950s and 1960s American culture, in the shadow of the Cold War. Programming Theater History curates these notes, with a selection of The Workshop’s incrementally artful, alluring program covers, Blau’s recollections, and evocative production photographs, into a narrative of indispensable artefacts and observations. The result is an inspiring testimony by a giant of American performance theory and practice, and a unique refl ection of what it is to create theatre history in the present. Herbert Blau is Byron W. and Alice L. Lockwood Professor Emeritus of the Humanities at the University of Washington, USA. -

Broadway Flops, Broadway Money, and Musical Theater Historiography

arts Article How to Dismantle a [Theatric] Bomb: Broadway Flops, Broadway Money, and Musical Theater Historiography Elizabeth L. Wollman The Department of Fine and Performing Arts, Baruch College, The City University of New York (CUNY), New York, NY 10010, USA; [email protected] Received: 7 May 2020; Accepted: 26 May 2020; Published: 29 May 2020 Abstract: The Broadway musical, balancing as it does artistic expression and commerce, is regularly said to reflect its sociocultural surroundings. Its historiography, however, tends for the most part to emphasize art over commerce, and exceptional productions over all else. Broadway histories tend to prioritize the most artistically valued musicals; occasional lip service, too, is paid to extraordinary commercial successes on the one hand, and lesser productions by creators who are collectively deemed great artists on the other. However, such a historiography provides less a reflection of reality than an idealized and thus somewhat warped portrait of the ways the commercial theater, its gatekeepers, and its chroniclers prioritize certain works and artists over others. Using as examples Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death (1971), Merrily We Roll Along (1981), Carrie (1988), and Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark (2011), I will suggest that a money-minded approach to the study of musicals may help paint a clearer picture of what kinds of shows have been collectively deemed successful enough to remember, and what gets dismissed as worthy of forgetting. Keywords: Broadway musicals; Broadway flops; commercial theater industry; Carrie; Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark; Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death; Merrily We Roll Along; theater economics 1. -

HERBERT BLAU Degrees: Ph.D. 1954 Stanford University

HERBERT BLAU Degrees: Ph.D. 1954 Stanford University (English/American Literature) M.A. 1949 Stanford University (Speech and Drama) B.Ch.E. 1947 New York University (Chemical Engineering) Academic Experience 2000- Byron W. and Alice L. Lockwood Professor in the Humanities (English and Comparative Literature) and Adjunct Professor in School of Drama, University of Washington 1984-00 Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature, University of Wisconsin--Milwaukee 1978-84 Professor of English, University of Wisconsin--Milwaukee 1974-78 Dean, Division of Arts and Humanities, and Professor of English, University of Maryland--Baltimore Co. 1972-74 Professor of the Arts (College and Conservatory) and Director of Inter-Arts Program, Oberlin College 1968-71 Founding Provost, and Dean of the School of Theater and Dance, California Institute of the Arts 1967-68 Professor of English, City College of the City University of New York 1950-65 Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor of English and World Literature, San Francisco State University Theater Experience 1971-81 Founder and Artistic Director, KRAKEN 1965-67 Co-Director, Repertory Theater of Lincoln Center, New York 1952-65 Co-Founder and Co-Director, The Actor's Workshop of San Francisco Other Academic Appointments 2006 Research Seminar, Institute for Theater Studies, Berlin 1995 Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Copenhagen, Denmark 1993 Visiting Professor, University of Mainz, Germany 1984 Visiting Professor, University of the Bosphorus, Turkey -

Introduction 3

Reality Principles: From the Absurd to the Virtual Herbert Blau The University of Michigan Press, 2011 http://press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=3119291 Introduction 3 All of these essays, with one exception, were written just before or after the millennium, and while they re›ect upon each other, that ear- lier essay does, not only across the years, but from so long ago that I might have forgotten what it was about. It would seem to have been an irrelevance until, working on an autobiography, I happened to read it again, while remembering the dissident 1960s, spilling into the 70s, when classrooms were invaded, students were lecturing teachers, and relevance was a watchword. That my view of it all then, as a rather chas- tening lesson, is still germane today was con‹rmed by my wife Kath- leen Woodward, when she was recently asked to contribute to a special issue of Daedalus, where my essay was published over forty years ago, after a rather high-powered conference, sponsored by the American Academy of Arts and Science, “The Future of the Humanities.” That the future is still in question—and with the economy reeling, the job market worse than ever—is what Kathy was writing about.1 Much involved as she is with the digital humanities, a possible source of sal- vation, about which I know very little, she nevertheless quoted me in her essay (without saying I was her husband), because “Relevance: The Shadow of a Magnitude” had apparently left a reproachful shadow on what, in the academy today, remains misguided, unthought, or know- ingly hypocritical. -

A Bibliography THESIS MASTER of ARTS

3 rlE NO, 6 . Articles on Drama and Theatre in Selected Journals Housed in the North Texas State University Libraries: A Bibliography THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Jimm Foster, B.A. Denton, Texas December, 1985 Foster, Jimm, Articles on Drama and Theatre in Texas State Selected Journals Housed in the North Master of Arts University Libraries: A Bibliography. 33 (Drama), December, 1985, 436 pp., bibliography, titles. The continued publication of articles concerning has drama and theatre in scholarly periodicals to the resulted in the "loss" of much research due to lack of retrieval tools. This work is designed the articles partially fill this lack by cassifying Trussler's found in fourteen current periodicals using taxonomy. Copyright by Jimm Foster 1985 ii - - - - - - - - - -- - -- - - - 4e.1J.metal,0..ilmis!!,_JGhiin IhleJutiJalla 's.lltifohyf;')Mil ;aAm"d="A -4-40---'+ .' "--*-0- -'e-"M."- - '*- -- - - -- - -" "'--- -- *- -"- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page * . - . v INTRODUCTION Chapter . - . - - - . I. REFERENCE - '. 1 OF THE 10 II. STUDY AND CRITICISM 10 PERFORMING ARTS . .. *. - - - * - 23 III. THEATRE AND EDUCATION IV. ANCIENT AND CLASSICAL DRAMA 6161-"-" AND THEATRE.. 67 THEATRE . - - - * V. MODERN DRAMA AND THEATRE . " - - 70 VI. EUROPEAN DRAMA AND THEATRE . * . - 71 VII. ITALIAN DRAMA AND THEATRE . - - 78 VIII. SPANISH DRAMA AND 85 THEATRE . - . IX. FRENCH DRAMA AND . 115 AND THEATRE . - - X. GERMAN DRAMA AND DUTCH DRAMA 130 XI. BELGIAN - 1 AND THEATRE . - THEATRE . " - - 133 XII. AUSTRIAN DRAMA AND 137 THEATRE . - - - XIII. SWISS DRAMA AND DRAMA XIV. EASTERN EUROPEAN ANDTHEATRE . -. 140 THEATRE . 147 XV. MODERN GREEK DRAMA AND 148 AND THEATRE . -

The Faith-Based Initiative of the Theater of the Absurd Herbert Blau

Fall 2001 3 The Faith-Based Initiative of the Theater of the Absurd Herbert Blau Some prefatory words, or what, in more classical times, might have been called an apology. In the invitation to this symposium,1 the topic proposed for me was "The Raging Soul of the Absurd." I don't know whether that came out of some tongue-in-cheek take on my temperament derived from the rather reticent things I've written, but as it turns out, though I've used another title, I will be saying something of the soul, not exactly raging, in another context. There was also a warning with the invitation—and I hope to be forgiven for saying so—that the audience here was not likely to "consist of specialists or academics per se," but rather a group of that "dying breed, the 'educated public,' which means we need to keep vocabulary relatively jargon free and inclusive." As it happens, that gave me the idea for what I have written about, while feeling somewhat like Jack, in Jack or the Submission, when he's told he's "chronometrable"—meaning, perhaps, it's time for him to change—after exclaiming, "Oh words, what crimes are committed in your name!" This leads to his agreeing to "abide by the circumstances,... the game of the rule," acceding to the familiar, "Oh well, yes, yes, na, I adore hashed brown potatoes."2 Which, actually, I try to avoid, though that may not keep me, with respect for the game of the rule, from making a hash of words, or to use a word coming up later, an "assemblage." Chronometrably, I might even wish that Roberta II—Jack's fiancee with three noses—were right and all we'd need "to designate things is one single word: cat," the word chat, of course, used as a prefix, sexier in French, though "The cat's got my tongue," able thus to accommodate all propositions.