Putting Health Care Reform on Its Deathbed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribune of the People: Maintaining the Legitimacy of Aggressive Journalism1 Steven E

Tribune of the people: maintaining the legitimacy of aggressive journalism1 Steven E. Clayman UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES Like other societal institutions, the institution of American journalism confronts a problem of legitimation. In order to be granted continued access to the corridors of power and to maintain the trust of news consumers, the journalistic enterprise must be perceived as essentially valid and legitimate (Hallin, 1994; Tuchman, 1978). As Hallin (1994: 32) has observed: The media have to attend to their own legitimacy. They must maintain the integrity of their relationship with the audience and also the integrity of their own self-image and of the social relationships that make up the profession of journalism. Moreover, rather than being a static phenomenon, legitimacy requires ongoing maintenance and upkeep. Because the practice of journalism frequently tramples on prestigious individuals and institutions, its legiti- macy is recurrently questioned both by news subjects themselves and by members of the public. Aggressive journalists are particularly vulnerable to the charge of having gone beyond the bounds of professionalism or propriety. To insulate themselves from external pressure and more generally to maintain a semblance of legitimacy, journalists draw on a variety of resources,2 one of which is to align themselves with the public at large. The role of public servant has deep historical roots within the profession (Schiller, 1981; Schudson, 1978) and it continues to have salience today, not only as a normative ideal that journalists strive for but also as a strategic legitimating resource. It is no coincidence that ‘tribune’ remains a Media, Culture & Society © 2002 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi), Vol. -

Flemming, Arthur S.: Papers, 1939-1996

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS FLEMMING, ARTHUR S.: PAPERS, 1939-1996 Accession: 86-18, 97-7, 97-7/1, 99-3 Processed by: DES Date Completed: 2005 On October 23, 1985 Arthur S. Flemming executed an instrument of gift for these papers. Linear feet: 128.8 Approximate number of pages: 254,400 Approximate number of items: Unknown Literary rights in the unpublished papers of Arthur S. Flemming have been transferred to the people of the United States. By agreement with the donor the following classes of documents will be withheld from research use: 1. Papers and other historical material the disclosure of which would constitute an invasion of personal privacy or a libel of a living person. 2. Papers and other historical materials that are specifically authorized under criteria established by statute or Executive Order to be kept secret in the interest of national defense or foreign policy, and are in fact properly classified pursuant to such statute or Executive Order. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE The Papers of Arthur S. Flemming were deposited with the Eisenhower Library in two major accessions. The first and largest accession arrived in 1986 and contained materials from Flemming’s early civil service career through the mid-1970s. The second accession arrived in late 1996. It more or less takes up where the first accession leaves off but there are a couple exceptions that must be noted. The second accession contains a few files from the early 1960s, which were probably held back at the time of the first shipment because they were still relevant to Flemming’s activities at the time, namely files related to aging. -

On Protecting Children from Speech Amitai Etzioni

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 79 Issue 1 Symposium: Do Children Have the Same First Article 2 Amendment Rights as Adults? April 2004 On Protecting Children from Speech Amitai Etzioni Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the First Amendment Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Juvenile Law Commons Recommended Citation Amitai Etzioni, On Protecting Children from Speech, 79 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 3 (2004). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol79/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON PROTECTING CHILDREN FROM SPEECH AMITAI ETZIONI* INTRODUCrION When freedom of speech comes into conflict with the protection of children, how should this conflict be resolved? What principles should guide such deliberations? Can one rely on parents and educa- tors (and more generally on voluntary means) to protect children from harmful cultural materials (such as Internet pornography and violent movies) or is government intervention necessary? What dif- ference does historical context make for the issue at hand? Are all minors to be treated the same? What is the scope of the First Amendment rights of children in the first place? These are the ques- tions here explored. The approach here differs from two polar approaches that can be used to position it. According to a key civil libertarian position, mate- rials that are said to harm children actually do not have such an effect, and even if such harm did exist, adults should not be reduced to read- ing only what is suitable for children. -

FCC Don't Let These Men Extinguish FCC Docket MM 99-25 LPFM. the Men of the House of Crooks Run and Tell This Man What to Do! Te

FCC Don't Let these men Extinguish FCC Docket MM 99-25 LPFM. The Men of The House Of Crooks Run and tell this Man what to do! Texas Gov. George W. Bush After he and the Republicans Supervise the Country for 4 Years it will destroy the Republican Party for the Next 50 Years,Men of the House Of Crooks Relinquish your Elected Office,you are all Mentally Deficient. Bush Gets (Green) Stupid on His Face Over Reading List! Bush Caught In Book Blunder (SF Chronicle) Texas Gov. George W. Bush was asked in a survey recently to name his favorite book from childhood. He cited Eric Carle's ``The Very Hungry Caterpillar.'' Trouble is, it wasn't published until 1969 the year after he graduated from Yale. House of Crooks: These Men are leading the Republican Party to Doom,they are not Good Men they are all not Genuine! Member: Republican Party 310 First Street, S.E. Washington, DC 20003 Date: 11/4/99 From: Mr.Joseph D'Alessandro 94 Angola Estates Lewes,Delaware 19958 302-945-1554 Subject:Member # 8512 7568 1596 4858 ACLU Don't let these Men Who we Elected run our Country, Vote them out of Office they are Un-Ethical,No-Morals,and always cast the First Stone Aganist anyone they dislike they all have to many offense's to mention. Jesse Helms Aganist Woman Rights "Your tax dollars are being used to pay for grade school classes that teach our children that CANNIBALISM, WIFE-SWAPPING, and the MURDER of infants and the elderly are acceptable behavior. -

Geopolitics, Oil Law Reform, and Commodity Market Expectations

OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 63 WINTER 2011 NUMBER 2 GEOPOLITICS, OIL LAW REFORM, AND COMMODITY MARKET EXPECTATIONS ROBERT BEJESKY * Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................... ........... 193 II. Geopolitics and Market Equilibrium . .............. 197 III. Historical U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East ................ 202 IV. Enter OPEC ..................................... ......... 210 V. Oil Industry Reform Planning for Iraq . ............... 215 VI. Occupation Announcements and Economics . ........... 228 VII. Iraq’s 2007 Oil and Gas Bill . .............. 237 VIII. Oil Price Surges . ............ 249 IX. Strategic Interests in Afghanistan . ................ 265 X. Conclusion ...................................... ......... 273 I. Introduction The 1973 oil supply shock elevated OPEC to world attention and ensconced it in the general consciousness as a confederacy that is potentially * M.A. Political Science (Michigan), M.A. Applied Economics (Michigan), LL.M. International Law (Georgetown). The author has taught international law courses for Cooley Law School and the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, American Government and Constitutional Law courses for Alma College, and business law courses at Central Michigan University and the University of Miami. 193 194 OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 63:193 antithetical to global energy needs. From 1986 until mid-1999, prices generally fluctuated within a $10 to $20 per barrel band, but alarms sounded when market prices started hovering above $30. 1 In July 2001, Senator Arlen Specter addressed the Senate regarding the need to confront OPEC and urged President Bush to file an International Court of Justice case against the organization, on the basis that perceived antitrust violations were a breach of “general principles of law.” 2 Prices dipped initially, but began a precipitous rise in mid-March 2002. -

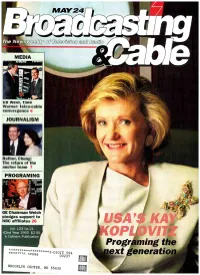

Ext Generatio

MAY24 The News MEDIA nuo11011 .....,1 US West, Time Warner: telco-cable convergence 6 JOURNALISM Rather, Chung: The return of the anchor team PROGRAMING GE Chairman Welch pledges support to NBC affiliates 26 U N!'K; Vol. 123 No.21 62nd Year 1993 $2.95 A Cahners Publication OP Progr : ing the no^o/71G,*******************3-DIGIT APR94 554 00237 ext generatio BROOKLYN CENTER, MN 55430 Air .. .r,. = . ,,, aju+0141.0110 m,.., SHOWCASE H80 is a re9KSered trademark of None Box ice Inc. P 1593 Warner Bros. Inc. M ROW Reserve 5H:.. WGAS E ALE DEMOS. MEN 18 -49 MEN 18 -49 AUDIENCE AUDIENCE PROGRAM COMPOSITION PROGRAM COMPOSITION STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE 9 37% WKRP IN CINCINNATI 25% HBO COMEDY SHOWCASE 35% IT'S SHOWTIME AT APOLLO 24% SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE 35% SOUL TRAIN 24% G. MICHAEL SPORTS MACHINE 34% BAYWATCH 24% WHOOP! WEEKEND 31% PRIME SUSPECT 24% UPTOWN COMEDY CLUB 31% CURRENT AFFAIR EXTRA 23% COMIC STRIP LIVE 31% STREET JUSTICE 23% APOLLO COMEDY HOUR 310/0 EBONY JET SHOWCASE 23% HIGHLANDER 30% WARRIORS 23% AMERICAN GLADIATORS 28% CATWALK 23% RENEGADE 28% ED SULLIVAN SHOW 23% ROGGIN'S HEROES 28% RUNAWAY RICH & FAMOUS 22% ON SCENE 27% HOLLYWOOD BABYLON 22% EMERGENCY CALL 26% SWEATING BULLETS 21% UNTOUCHABLES 26% HARRY & THE HENDERSONS 21% KIDS IN THE HALL 26% ARSENIO WEEKEND JAM 20% ABC'S IN CONCERT 26% STAR SEARCH 20% WHY DIDN'T I THINK OF THAT 26% ENTERTAINMENT THIS WEEK 20% SISKEL & EBERT 25% LIFESTYLES OF RICH & FAMOUS 19% FIREFIGHTERS 25% WHEEL OF FORTUNE - WEEKEND 10% SOURCE. NTI, FEBRUARY NAD DATES In today's tough marketplace, no one has money to burn. -

2006-2007 Impact Report

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION The Global Network for Women in the News Media 2006–2007 Annual Report From the IWMF Executive Director and Co-Chairs March 2008 Dear Friends and Supporters, As a global network the IWMF supports women journalists throughout the world by honoring their courage, cultivating their leadership skills, and joining with them to pioneer change in the news media. Our global commitment is reflected in the activities documented in this annual report. In 2006-2007 we celebrated the bravery of Courage in Journalism honorees from China, the United States, Lebanon and Mexico. We sponsored an Iraqi journalist on a fellowship that placed her in newsrooms with American counterparts in Boston and New York City. In the summer we convened journalists and top media managers from 14 African countries in Johannesburg to examine best practices for increasing and improving reporting on HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. On the other side of the world in Chicago we simultaneously operated our annual Leadership Institute for Women Journalists, training mid-career journlists in skills needed to advance in the newsroom. These initiatives were carried out in the belief that strong participation by women in the news media is a crucial part of creating and maintaining freedom of the press. Because our mission is as relevant as ever, we also prepared for the future. We welcomed a cohort of new international members to the IWMF’s governing board. We geared up for the launch of leadership training for women journalists from former Soviet republics. And we added a major new journalism training inititiative on agriculture and women in Africa to our agenda. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D. -

Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States

PUBLIC PAPERS OF THE PRESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES i VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:33 Nov 01, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1234 Sfmt 1234 C:\94PAP2\PAP_PRE txed01 PsN: txed01 ii VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:33 Nov 01, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 1234 Sfmt 1234 C:\94PAP2\PAP_PRE txed01 PsN: txed01 iii VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:33 Nov 01, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 1234 Sfmt 1234 C:\94PAP2\PAP_PRE txed01 PsN: txed01 Published by the Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, DC 20402 iv VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:33 Nov 01, 2000 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 1234 Sfmt 1234 C:\94PAP2\PAP_PRE txed01 PsN: txed01 Foreword During the second half of 1994, America continued to move forward to help strengthen the American Dream of prosperity here at home and help spread peace and democracy around the world. The American people saw the rewards that grew out of our efforts in the first 18 months of my Administration. Economic growth increased in strength, and the number of new jobs created during my Administration rose to 4.7 million. After 6 years of delay, the American people had a Crime Bill, which will put 100,000 police officers on our streets and take 19 deadly assault weapons off the street. We saw our National Service initiative become a reality as I swore in the first 20,000 AmeriCorps members, giving them the opportunity to serve their country and to earn money for their education. -

Aspen Ideas Festival Confirmed Speakers

Aspen Ideas Festival Confirmed Speakers Carol Adelman , President, Movers and Shakespeares; Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Global Prosperity, The Hudson Institute Kenneth Adelman , Vice President, Movers and Shakespeares; Executive Director, Arts & Ideas Series, The Aspen Institute Stephen J. Adler , Editor-in-Chief, BusinessWeek Pamela A. Aguilar , Producer, Documentary Filmmaker; After Brown , Shut Up and Sing Madeleine K. Albright , founder, The Albright Group, LLC; former US Secretary of State; Trustee, The Aspen Institute T. Alexander Aleinikoff , Professor of Law and Dean, Georgetown University Law Center Elizabeth Alexander , Poet; Professor and Chair, African American Studies Department, Yale University Yousef Al Otaiba , United Arab Emirates Ambassador to the United States Kurt Andersen , Writer, Broadcaster, Editor; Host and Co-Creator, Public Radio International’s “Studio 360” Paula S. Apsell , Senior Executive Producer, PBS’s “NOVA” Anders Åslund , Senior Fellow, Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics Byron Auguste , Senior Partner, Worldwide Managing Director, Social Sector Office, McKinsey & Company Dean Baker , Co-Director, Center for Economic and Policy Research; Columnist, The Guardian ; Blogger, “Beat the Press,” The American Prospect James A. Baker III , Senior Partner, Baker Botts, LLP; former US Secretary of State Bharat Balasubramanian , Vice President, Group Research and Advanced Engineering; Product Innovations & Process Technologies, Daimler AG Jack M. Balkin , Knight Professor of Constitutional -

Contact the Phoenix Project

CONTACT THE PHOENIX PROJECT “YE SHALL KNOW THE TRUTH AND THE TRUTH SHALL MAKE YOU MAD!n VOLUME 7, NUMBER 10 NEWS REVIEW $ 3.00 JANUARY 3, 1995 SpotlightNow l?h$zg On Arkansas Gov. Guy Tucker Free RichardWavne Snell! J/2/95 #l HATONN EDITORIAL TO GOVERNOR GUY TUCKER, ARKANSAS: * Mr. Tucker-the eyes of the WORLD are focused ON YOU. We know you INSIDE THIS ISSUE thought the opening of 1995 would be parades of roses and re-inforced rings- through-noses as the New World Order settles in for the FINAL KILL. NO SIR, To Better See Our Plight, Look To Canadian Parasites, p.2 we-the-people are not only not going to march to the ring-bear-er, we aregoing to hang rings on or about the alternativeportions of anatomy of the PARASITES The (C.I.A.) Pipeline, Part XII, p.6 who have taken our FREE NATION which was once UNDER GOD WITH LIBERTY AND JUSTICE for ALL. Recent Sky Activity Is Secret Technology In Action, p.8 As you will find as you turn through this paper- WE KNOW!! We KNOW Donahue Show Tries To Railroad Militias, p.8 all about the antics and total miscarriage of all Justice in our sick judicial system and throughout the so-called *‘government(s)” of our also ONCE Great Parasites, Pets And Other Ethical Matters, p. 12 Nation. You have opportunity here, with the spotlight shining directly upon your Criminal Benchwarming Judges? Keep Patriot SpotIight Blazing, p. 14 person-to SERVE: the people, God and OUR Country. -

True Spies Episode 45 - the Profiler

True Spies Episode 45 - The Profiler NARRATOR Welcome ... to True Spies. Week by week, mission by mission, you’ll hear the true stories behind the world’s greatest espionage operations. You’ll meet the people who navigate this secret world. What do they know? What are their skills? And what would YOU do in their position? This is True Spies. NARRATOR CLEMENTE: With any equivocal death investigation, you have no idea where the investigation is going to take you, but in this particular investigation, it starts at the White House. That makes it incredibly difficult to conduct an investigation, when you know that two of the people that are intimately involved in it are the First Lady and the President of the United States. NARRATOR This is True Spies, Episode 45, The Profiler. This story begins with an ending. CLEMENTE: On the evening of January 20th, 1993, Vince Foster was found dead of by gunshot wound at the top of an earthen berm in Fort Marcy Park. NARRATOR A life cut short in a picturesque, wooded park 10 minutes outside of the US capital. He was found by someone walking through the park who then called the US park police. The park police and EMTs responded to the scene and the coroner then arrived and pronounced Foster dead. And his body was removed. NARRATOR A body, anonymous – housed in an expensive woolen suit, a crisp white dress shirt. A vivid bloodstain on the right shoulder. When they then searched his car that was in the parking lot they found a pass to the White House.