Growth and Convergence in the Central and East European Countries Towards EU /1992-2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invisible to the Eye, but Felt Strongly by the Heart

Issue 88 Fall 2019 NEWSLETTER Bulgarian-American Commission for Educational Exchange Invisible to the Eye, But Felt Strongly by the Heart Media Literacy Matters Art by the Danube Strategies for Strengthening Democracy The Fulbright Bulgaria Newsletter is a biannual magazine published by the Bulgarian-American Commission for Educational Exchange (Fulbright) in print and electronically. Opinions expressed by the authors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of the Bulgarian-American Commission for Educational Exchange. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the material in this publication, the Bulgarian-American Commission for Educational Exchange does not accept liability for any errors or omissions. BULGARIAN-AMERICAN COMMISSION FULBRIGHT BULGARIA STAFF FOR EDUCATIONAL EXCHANGE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Angela Rodel Executive Director Krassimir Valchev US MEMBERS: [email protected] Minister of Education and Science Mathew Hagengruber Honorary Co-Chairperson Treasurer, Attaché Anastassia Miteva for Educational and Financial Officer [email protected] Herro Mustafa Cultural Affairs US Ambassador to Bulgaria US Embassy Tanya Petrova Honorary Co-Chairperson Accountant/Cashier Sarah Perrine [email protected] BULGARIAN MEMBERS: Executive Director Trust for Social Achievement Maria Kostova Karina Angelieva Program Officer, Bulgarian Grantees Deputy Minister of Education Drake Weisert [email protected] Counselor for Public Affairs Iliana Dimitrova Georg Georgiev US Embassy Program Officer, ETA Program Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs [email protected] Jeffery Warner Radostina Chaprazova Evaluation Officer Rada Kaneva Executive Director Trust for Social Achievement Program Officer, U.S. Grantees Arete Youth Foundation [email protected] Dr. Richard T. Ewing, Jr. Snejana Teneva Dr. Julia Stefanova President Educational Advisor Former Executive Director American College of Sofia [email protected] of the Bulgarian Fulbright Commission Lyra Konstantinova Dr. -

Models of Architecture from the Middle Ages to Present on the Valley of Struma River

MODELS OF ARCHITECTURE FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO PRESENT ON THE VALLEY OF STRUMA RIVER Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria Brestovo Monastery “St. Archangel Michael”, Municipality of Simitly, Bulgaria Pirin village, Bulgaria Melnik, Bulgaria Serres, Greece Blagoevgrad is the largest city in Southwest Bulgaria, the administrative center of Blagoevgrad District and Blagoevgrad Municipality. It is situated at the foot of the southwestern slopes of the Rila Mountain, in the valley of the Struma River, 100 km south from the capital Sofia. The city is located on the two banks of the Bistritsa river, just before its inflow into the Struma River. Besides the clear waters of the river, important factors for the development of the city were the mineral springs and the favorable central location of the city, situated between Sofia and Thessaloniki, Kyustendil and Razlog. About 35 km away from the city, in the upper course of the Bistritsa River, is located the ancient Parangalitsa forest - one of the most valuable reserves in Bulgaria. In 1973, it was proclaimed by UNESCO as a Biosphere Reserve. The history of Blagoevgrad dates back to 10th century BC. The Thracian settlement Skaptopara (Upper Market) was founded around the mineral springs around 300 BC. This settlement has been associated with the Thracian tribe Denteleti who inhabited the upper valley of the Struma River. In the 1st century AD the Thracians were conquered by the Romans. A Roman settlement from 3rd-5th century has been discovered in 2017, near the village of Pokrovnik, about 3 km from Blagoevgrad. The establishment’s location did coincide with the planned route of Struma highway and it has been destroyed, with only a few of the excavated buildings being moved away from the road. -

Relics of the Bulgarian National Epic

PAISStt OF HILENDAR: FOUNDER OF THE NATIONAL IDEOLOGY In modern historiography the first centuries of the of the respectful image of Mediaeval Bulgaria. In Sremski Ottoman rule of Bulgarian lands are determined as Late Karlovci, one of the most active literary centres of the Middle Ages. The time from the beginning of the 18th time, Paissi read the book of Dubrovnik Abbot Mavro century to the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish War is called Orbini "The Realm of the Slavs" in which he discovered Bulgarian National Revival. If the National Revival period considerable evidence about the Bulgarians' past. for Northern Bulgaria and the Sofia Region continued by In 1762 he completed "Slav-Bulgarian History, about 1878, for Eastern Rumelia it was by 1885 and for the People and the Kings, the Bulgarian Saints and All Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace by 1912-1913. Bulgarian Activities and Events". In 83 hand-written The National Revival in the Bulgarian lands witnessed pages the inspired Hilendar Monk interpreted using considerable economic progress. The Bulgarian were romantic and heightened tone the grandour of increasingly getting rid of their mediaeval restricted out- Mediaeval Bulgaria, the victory of the Bulgarian army look and helplessness and were gradually getting aware over Byzantium, the impressive bravery and manliness of as people, aspiring towards economic and cultural the Bulgarians, the historic mission of the Cyril and progress. Hilendar monk Paissii became a mouthpiece of Methodius brothers and other eloquent facts, worthy to these changes in the national self-awareness. He was be remembers and respected by the successors. Already the first to perceive the beginning of the new time and in the forward this noted Bulgarian appealed with gen- the need of formulating verbally the maturing historical uine sincerity towards his compatriots to love and keep prospects and tasks before the Bulgarian people. -

Reception Booklet of Aiesec Lc Svishtov

RECEPTIONRECEPTION BOOKLETBOOKLET OFOF LCLC SVISHTOVSVISHTOV Dear Trainee, If you are reading this message it means that you are facing the challenge to get known Bulgaria - its culture, its spirit, the way people live, work… and have fun. Our reception booklet is prepared as a guide for you in help of your integration and perception of Bulgarian lifestyle. It contains some useful information you will need in your preparation for coming to Bulgaria. So my advice for you is to read it carefully and thus help us to help you in making your staying here comfortable and enjoyable. In case you have any kind of problems your reception officer (RO) will be happy to help you. BulgariaBulgaria MAPMAP BULGARIABULGARIA ININ BRIEFBRIEF • Bulgaria is situated on the Balkan Peninsula and covers part of the Southeastern Europe. Its boundaries are with Romania to the North, ex-Yugoslavia to the West, Black Sea to the East, Greece to the South and Turkey to the Southeast part of the land. • TERRITORY: 111 000 km2 • POPULATION: Apr. 8 millions • CAPITAL: Sofia • LANGUAGE: Bulgarian belongs to the group of the Slavic languages • RELIGION: Predominantly Eastern Orthodox. The Bulgarian church is autonomous and headed by a Patriarch. SVISHTOVSVISHTOV BeforeBefore && NowNow HistoryHistory • Svishtov is a small town beautifully situated on the Danube River, in the northern part of Bulgaria. It has rich and fascinating history. During the 3-4 c. B.C. there was a Roman fortress, which remains can be still seen in the suburbs of the city. • The name Svishtov originates from the word "light", "candle" because in the past people used to make fires on the highest point of the town as an orientation for fishermen. -

USAID/Bulgaria List of Legacy Organizations (February 2008)

USAID/Bulgaria List of Legacy Organizations (February 2008) Governing Justly and Democratically...............................................................2 American University in Bulgaria, The (AUBG).......................................................................2 Association of Community Funds in Bulgaria (ACFB)............................................................3 Association of Danube River Municipalities (ADRM).............................................................4 Association of Rhodope Municipalities (ARM)........................................................................5 Association of South-West Municipalities................................................................................6 Broadcast Training Center Foundation (BTC) - ProMedia .....................................................7 Bulgarian Association for Alternative Dispute Resolution (BAADR)......................................8 Bulgarian Center for Not-for-Profit Law (BCNL)....................................................................9 Bulgarian Institute for Legal Reform Initiatives (BILI) .........................................................10 Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD).............................................................................11 Foundation for Local Government Reform (FLGR)...............................................................13 Legal Clinic with Angel Kunchev University, Rousse............................................................15 Legal Clinic with St. Kiril and Methodiy -

Undergraduate Catalog

3 1 0 2 - 2 1 0 2 UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG American University in Bulgaria Main Building 1 Georgi Izmirliev Sq. Blagoevgrad 2700, Bulgaria President’s Office: (+359 73) 888 307 Admissions: (+359 73) 888 235 Development: (+359 73) 888 366 Fax: (+359 73) 883 227 Balkanski Academic Center 54 Alexander Stamboliyski St. Skaptopara Campus Blagoevgrad 2700, Bulgaria AUBG - Sof ia Elieff Center for Education and Culture 1 Universitetski Park St., Studentski Grad Sofia 1700, Bulgaria Switchboard: (+359 2) 960 7910 Fax: (+359 2) 961 6010 U.S. Mailing Address: American University in Bulgaria 910 17th St., N.W. Suite 1100 Washington, D.C. 20006 www.aubg.bg 2012 - 2013 This catalog was prepared on the basis of the best information available at the time of publication. All information, including statements of tuition and fees, course offerings, policies, and admission and graduation requirements, is subject to change without notice or obligation. Updates after publication can be found at www.aubg.bg/catalog ACADEMIC CALENDAR TABLE OF CONTENTS Fall 2012 Orientation Begins August 20 ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY ............................................................................... 4 Classes Begin August 27 ADMISSIONS ................................................................................................... 12 Student Sign-in Deadline (5:00 pm) August 29 Unification Day Holiday September 6 TUITION AND FEES ........................................................................................ 18 Bulgaria Independence Day Holiday September 22 FINANCIAL -

България Bulgaria Държава Darzhava

Проект "Разбираема България" Вид Транслитера Собствено име Транслитерация на собственото име Вид обект Транслитерация Местоположение Транслитерация местоположение ция България Bulgaria държава darzhava Абаджиев Abadzhiev фамилно име familno ime Абаджийска Abadzhiyska улица ulitsa Сливен Sliven град grad Абаносов Abanosov фамилно име familno ime Абдовица Abdovitsa квартал kvartal София Sofia град grad Абланица Ablanitsa село selo Абланов Ablanov фамилно име familno ime Абланово Ablanovo улица ulitsa Сливен Sliven град grad Абланово Ablanovo улица ulitsa Ямбол Yambol град grad Аблановска низина Ablanovska nizina низина nizina Абоба Aboba улица ulitsa Бургас Burgas град grad Абоба Aboba улица ulitsa Разград Razgrad град grad Абоба Aboba улица ulitsa София Sofia град grad Абрашев Abrashev фамилно име familno ime Абрашков Abrashkov фамилно име familno ime Абрит Abrit село selo Абритус Abritus улица ulitsa Разград Razgrad град grad Ав. Гачев Av. Gachev улица ulitsa Габрово Gabrovo град grad Ав. Митев Av. Mitev улица ulitsa Враца Vratsa град grad Ав. Стоянов Av. Stoyanov улица ulitsa Варна Varna град grad Аваков Avakov фамилно име familno ime Авгостин Avgostin лично име lichno ime Август Avgust лично име lichno ime Август Попов Avgust Popov улица ulitsa Шумен Shumen град grad Августа Avgusta лично име lichno ime Августин Avgustin лично име lichno ime Августина Avgustina лично име lichno ime Авджиев Avdzhiev фамилно име familno ime Аверкий Averkiy улица ulitsa Кюстендил Kyustendil град grad Авксентий Велешки Avksentiy Veleshki улица ulitsa Варна -

You Drive, We Care

You drive, we care. BG - Diesel & Services Bulgarien / Balgaria / Bulgaria PLZ sortiert Sorted by ZIP code » For help, call me! DKV ASSIST - 24h International Free Call* 00800 365 24 365 In case of difficulties concerning the number 00800 please dial the relevant emergency number of the country: Bei unerwarteten Schwierigkeiten mit der Rufnummer 00800, wählen Sie bitte die Notrufnummer des Landes: Andorra / Andorra Latvia / Lettland » +34 934 6311 81 » +370 5249 1109 Austria / Österreich Liechtenstein / Liechtenstein » +43 362 2723 03 » +39 047 2275 160 Belarus / Weißrussland Lithuania / Litauen » 8 820 0071 0365 (national) » +370 5249 1109 » +7 495 1815 306 Luxembourg / Luxemburg Belgium / Belgien » +32 112 5221 1 » +32 112 5221 1 North Macedonia / Nordmazedonien Bosnia-Herzegovina / Bosnien-Herzegowina » +386 2616 5826 » +386 2616 5826 Moldova / Moldawien Bulgaria / Bulgarien » +386 2616 5826 » +359 2804 3805 Montenegro / Montenegro Croatia / Kroatien » +386 2616 5826 » +386 2616 5826 Netherlands / Niederlande Czech Republic / Tschechische Republik » +49 221 8277 9234 » +420 2215 8665 5 Norway / Norwegen Denmark / Dänemark » +47 221 0170 0 » +45 757 2774 0 Poland / Polen Estonia / Estland » +48 618 3198 82 » +370 5249 1109 Portugal / Portugal Finland / Finnland » +34 934 6311 81 » +358 9622 2631 Romania / Rumänien France / Frankreich » +40 264 2079 24 » +33 130 5256 91 Russia / Russland Germany / Deutschland » 8 800 7070 365 (national) » +49 221 8277 564 » +7 495 1815 306 Great Britain / Großbritannien Serbia / Serbien » 0 800 1975 -

Project Plan for Sustainable Urban Transport Planning of the City of Gorna Oryahovitsa

Project Plan for sustainable urban transport planning of the city of Gorna Oryahovitsa 1 INTRODUCTION Over 60 % of the population of the European Union lives in cities, in Bulgaria this percent is even higher – 71.4%1. Almost 85 % of the gross domestic product of the EU is produced in the cities. The cities are the engine of the European and the national economies. They attract investments and new places of work and are especially necessary for the unobstructed functioning of the country’s economic life. Being the environment of the greatest part of the population, the city life standard, including the mobility problems, must be as high as possible. The trend of traffic becoming heavier in the central parts is valid for all European cities. It results in frequent traffic jams, with all the adverse consequences from them as time loss, higher risk of road accidents and pollution of the environment. As a result the European economy loses about 100 billion Euro or 1 % of the GDP of the EU. The atmospheric and the noise pollution increase every year. The city traffic is the reason for 40 % of the emissions of CO2 and 70 % of the emissions of the other pollutants originating from the road transport. At European level, the number of the road accidents in the cities increases every year: at present one of each three accidents with a lethal outcome occurs in the cities, and the most vulnerable, pedestrians and cyclists are most often the victims. In Bulgaria this parameter is even higher: 36% of the killed, 63% of the injured and 66% of the road accidents are registered in the residential areas 2. -

Undergraduate Catalog

5 1 0 2 - 4 1 0 2 UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG American University in Bulgaria 1 Georgi Izmirliev Sq. Blagoevgrad 2700, Bulgaria President’s Office: (+359 73) 888 307 Admissions: (+359 73) 888 111 Development: (+359 73) 888 366 Fax: (+359 73) 888 344 America for Bulgaria Student Center 12 Svoboda Bachvarova St. Skaptopara Campus Blagoevgrad 2700, Bulgaria AUBG - Sofia Elieff Center for Education and Culture 1 Universitetski Park St., Studentski Grad Sofia 1700, Bulgaria Switchboard: (+359 2) 960 7910 Fax: (+359 2) 961 6010 U.S. Mailing Address: American University in Bulgaria 910 17th St., N.W. Suite 1100 Washington, D.C. 20006 www.aubg.edu 2014 - 2015 This catalog was prepared on the basis of the best information available at the time of publication. All information, including statements of tuition and fees, course offerings, policies, and admission and graduation requirements, is subject to change without notice or obligation. Updates after publication can be found at www.aubg.edu/academic-catalog ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2014 - 2015 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2015 - 2016 Fall 2014 Fall 2015 Orientation Begins August 25 Orientation Begins August 24 Classes Begin September 1 Classes Begin August 31 Student Sign-in Deadline (5:00 pm) September 3 Student Sign-in Deadline (5:00 pm) September 2 Unification Day Holiday September 6 Unification Day Holiday September 6 Bulgarian Independence Day September 22 Bulgarian Independence Day September 22 Board Meeting October 17-19 Board Meeting October 16-18 Fall Break Begins October 27 Fall Break Begins October 26 National -

Concept Notes

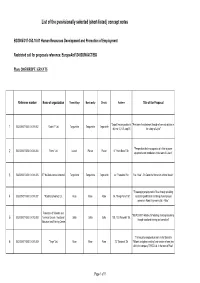

List of the pvovisionally selected (short-listed) concept notes BG2005/017-353.10.01 Human Resources Development and Promotion of Employment Restricted call for proposals reference: EuropeAid/124938/M/ACT/BG Phare 2005/HRDPE /GRANTS Reference number Name of organization Town/village Municipality District Address Title of the Proposal "Zapad" housing estate, bl. "Provision of employment through of concrete articles in BG2005/017-353.10.01-1.002 "Galant 7" Ltd. Targovishte Targovishte Targovishte 1 48, entr. C, fl. 5, app.15 the village of Lilyak" "Perspectives for the occupation of a fitter of power BG2005/017-353.10.01-1.004 "Yotovi" Ltd. Lukovit Pleven Pleven 6, "Hristo Botev" Str. 2 equipments and installations in the town of Lukovit" 3 BG2005/017-353.10.01-1.005 ST "Ka-Stela-Ivanka Antonova" Targovishte Targovishte Targovishte 44, "Trapezitsa" Str. "Ka - Stela" - To Carve the Stone with a Hand Master" "Encouraging employment in Ruse through providing 4 BG2005/017-353.10.01-1.007 "Road Engineering" Ltd. Ruse Ruse Ruse 14, "Olimpi Panov" Str vocational qualification and hiring of unemployed persons in Road Engineering Ltd. - Ruse" Federation of Scientific and "NEW START Initiative for fostering of entrepreneurship BG2005/017-353.10.01-2.008 Technical Unions - Vocational Sofia Sofia Sofia 108, "G.S.Rakovski" Str. 5 through vocational training and consulting" Education and Training Centre "Training of unemployed persons in the Speciality 6 BG2005/017-353.10.01-1.009 "Tergo" Ltd. Ruse Ruse Ruse 72, "Borisova" Str "Millwork and glass-installing" and creation of new jobs within the company TERGO Ltd. -

Erasmus Code Name of Organisation a BADEN01

Erasmus code Name of organisation A BADEN01 PAEDAGOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE NIEDERÖSTERREICH A DORNBIR01 FACHHOCHSCHULE VORARLBERG GMBH A EISENST01 STIFTUNG PRIVATE PÄDAGOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE BURGENLAND A EISENST02 FACHHOCHSCHULE BURGENLAND GMBH A EISENST05 JOSEPH HAYDN KONSERVATORIUM DES LANDES BURGENLAND A FELDKIR01 PÄDAGOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE VORARLBERG A FELDKIR03 VORARLBERGER LANDESKONSERVATORIUM A GRAZ01 UNIVERSITAET GRAZ A GRAZ02 TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITAET GRAZ A GRAZ03 UNIVERSITAT FUR MUSIK UND DARSTELLENDE KUNST GRAZ (KUG) A GRAZ04 UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF TEACHER EDUCATION STYRIA A GRAZ08 KIRCHLICHE PÄDAGOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE DER DIÖZESE GRAZ-SECKAU A GRAZ09 FH JOANNEUM GESELLSCHAFT M.B.H. A GRAZ10 CAMPUS 02 FACHHOCHSCHULE DER WIRTSCHAFT GMBH A GRAZ23 MEDIZINISCHE UNIVERSITAT GRAZ A INNSBRU01 UNIVERSITAET INNSBRUCK A INNSBRU03 PÄDAGOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE TIROL A INNSBRU08 MCI MANAGEMENT CENTER INNSBRUCK INTERNATIONALE HOCHSCHULE GMBH PRIVATE PÄDAGOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE - HOCHSCHULSTIFTUNG DER DIÖZESE A INNSBRU09 INNSBRUCK UMIT- PRIVATE UNIVERSITAT FUER GESUNDHEITSWISSENSCHAFTEN, A INNSBRU20 MEDIZINISCHEINFORMATIK UND TECHNIK GMBH A INNSBRU21 MEDIZINISCHE UNIVERSITAT INNSBRUCK A INNSBRU23 FHG - ZENTRUM FUER GESUNDHEITSBERUFE TIROL GMBH A KLAGENF01 UNIVERSITAET KLAGENFURT A KLAGENF02 PÄDAGOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE KÄRNTEN A KLAGENF06 KÄRNTNER LANDESKONSERVATORIUM A KLOSTER01 Institute of Science and Technology Austria A KREMS03 IMC FACHHOCHSCHULE KREMS GMBH A KREMS05 UNIVERSITAET FUER WEITERBILDUNG KREMS KARL LANDSTEINER PRIVATUNIVERSITÄT FÜR GESUNDHEITSWISSENSCHAFTEN