S41467-020-18512-7 OPEN Dental Cell Type Atlas Reveals Stem and Differentiated Cell Types in Mouse and Human Teeth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ono -- PTH-Pthrp Receptor Signaling in Osterix-Expressing Progenitors.Pdf

3/27/14 Root forma)on Cementum Dentin Cementoblast Odontoblast Role of PTH/PTHrP Receptor Signaling on Root Epithelial rests Formaon of Malassez (ERM) Dental Wanida Ono papilla cells AGE Orthodon;cs, Department of Developmental Biology, Harvard School of Dental Medicine Endocrine Unit, MassachuseLs General Hospital and Harvard Medical School Dental follicle cells Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath (HERS) Osterix PTHrP-PPR system • Transcripon factor essen;al to osteoblast differen;aon PTHrP (Nakashima K et al. 2002) PTH/PTHrP receptor (PPR) • Expressed in odontoblasts and alveolar osteoblasts during Gαs Gq tooth development (Chen S et al. 2009) • Controls cellular cementum formaon (Cao Z et al. 2012) • Mediates epithelial-mesenchymal interacons • Osterix-expressing precursors in the perichondrium move • PTHrP is expressed in enamel epithelia/HERS? to bone marrow and become osteoblasts during fetal • PPR is expressed in dental mesenchymes development (Maes C, Kronenberg HM et al. 2010) (Beck et al 1995; Lee Deeds and Segre 1995; Liu et al 1998) • PTHrP is required for tooth erup;on in mice (Philbrick WM, Karaplis AC et al. PNAS 1998) Osterix+ Root-forming • PPR haploinsufficiency is associated with primary cells progenitors failure of tooth erup;on (PFE) in humans ? (Decker E, Weber BH et al. Am J Hum Gen 2008) PTHrP expression paern during root morphogenesis Aims of this study PTHrPLacZ/+ x40 P7 P14 P49 • Iden;fy how osterix-expressing progenitors contribute to murine root morphogenesis • Understand how PTH/PTHrP receptor signal regulates root-forming progenitors PTHrP-LacZ x200 P7 x400 P14 ? PTHrP Epithelial root sheath PPR PTHrP-LacZ Osx+ progenitors Odontoblast PTHrP par;cipates in ……. -

Experimental Induction of Odontoblast Differentiation and Stimulation During Preparative Processes

Cells and Materials Volume 3 Number 2 Article 8 1993 Experimental Induction of Odontoblast Differentiation and Stimulation During Preparative Processes H. Lesot Institut de Biologie Médicale C. Begue-Kirn Institut de Biologie Médicale M. D. Kubler Institut de Biologie Médicale J. M. Meyer Institut de Biologie Médicale A. J. Smith Dental School, Birmingham See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cellsandmaterials Part of the Biomedical Engineering and Bioengineering Commons Recommended Citation Lesot, H.; Begue-Kirn, C.; Kubler, M. D.; Meyer, J. M.; Smith, A. J.; Cassidy, N.; and Ruch, J. V. (1993) "Experimental Induction of Odontoblast Differentiation and Stimulation During Preparative Processes," Cells and Materials: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cellsandmaterials/vol3/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Dairy Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cells and Materials by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Experimental Induction of Odontoblast Differentiation and Stimulation During Preparative Processes Authors H. Lesot, C. Begue-Kirn, M. D. Kubler, J. M. Meyer, A. J. Smith, N. Cassidy, and J. V. Ruch This article is available in Cells and Materials: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cellsandmaterials/vol3/iss2/8 Cells and Materials, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1993 (Pages201-217) 1051-6794/93$5. 00 +. 00 Scanning Microscopy International, Chicago (AMF O'Hare), IL 60666 USA EXPERIMENTAL INDUCTION OF ODONTOBLAST DIFFERENTIATION AND STIMULATION DURING REPARATIVE PROCESSES 1 1 1 2 2 1 H. -

Journal of Dental Research

Journal of Dental Research http://jdr.sagepub.com/ Cell Differentiation and Matrix Organization in Engineered Teeth A. Nait Lechguer, M.L. Couble, N. Labert, S. Kuchler-Bopp, L. Keller, H. Magloire, F. Bleicher and H. Lesot J DENT RES 2011 90: 583 originally published online 4 February 2011 DOI: 10.1177/0022034510391796 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jdr.sagepub.com/content/90/5/583 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: International and American Associations for Dental Research Additional services and information for Journal of Dental Research can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jdr.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jdr.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Apr 13, 2011 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Feb 4, 2011 What is This? Downloaded from jdr.sagepub.com at Service Commun de la Documentation Université de Strasbourg on September 6, 2013 For personal use only. No other uses without permission. © 2011 International & American Associations for Dental Research RESEARCH REPORTS Biomaterials & Bioengineering A. Nait Lechguer1,2, M.L. Couble3,4, N. Labert3,4, S. Kuchler-Bopp1,2, Cell Differentiation and L. Keller1,2, H. Magloire3,4, F. Bleicher3,4, Matrix Organization in and H. Lesot1,2* Engineered Teeth 1INSERM UMR 977, Faculté de Médecine, 11, rue Humann, F-67085 Strasbourg, France; 2Dental School, University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France; 3Université de Lyon, Faculté d’Odontologie, Rue Guillaume Paradin, F-69372 Lyon Cedex 08, France; and 4IGFL, CNRS UMR 5242, Ecole Normale Supérieure, 46 Allée d’Italie, 69364, Lyon Cedex 08, France; *corresponding author, [email protected] J Dent Res 90(5):583-589, 2011 ABSTRACT InTRODuCTIOn Embryonic dental cells were used to check a series of criteria to be achieved for tooth engineering. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list Citation for published version: Davenport, AP, Alexander, SPH, Sharman, JL, Pawson, AJ, Benson, HE, Monaghan, AE, Liew, WC, Mpamhanga, CP, Bonner, TI, Neubig, RR, Pin, JP, Spedding, M & Harmar, AJ 2013, 'International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list: recommendations for new pairings with cognate ligands', Pharmacological reviews, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 967-86. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1124/pr.112.007179 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Pharmacological reviews Publisher Rights Statement: U.S. Government work not protected by U.S. copyright General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1521-0081/65/3/967–986$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 65:967–986, July 2013 U.S. -

Supplementary Data

Supplemental Data A novel mouse model of X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: Phenotypic analysis and therapeutic implications Jian Hua Li, Chung-Lin Chou, Bo Li, Oksana Gavrilova, Christoph Eisner, Jürgen Schnermann, Stasia A. Anderson, Chu-Xia Deng, Mark A. Knepper, and Jürgen Wess Supplemental Methods Metabolic cage studies. Animals were maintained in mouse metabolic cages (Hatteras Instruments, Cary, NC) under controlled temperature and light conditions (12 hr light and dark cycles). Mice received a fixed daily ration of 6.5 g of gelled diet per 20 g of body weight per day. The gelled diet was composed of 4 g of Basal Diet 5755 (Test Diet, Richmond, IN), 2.5 ml of deionized water, and 65 mg agar. Preweighted drinking water was provided ad libitum during the course of the study. Mice were acclimated in the metabolic cages for 1-2 days. Urine was collected under mineral oil in preweighted collection vials for successive 24 hr periods. Analysis of GPCR expression in mouse IMCD cells via TaqMan real-time qRT-PCR. Total RNA prepared from mouse IMCD tubule suspensions was reverse transcribed as described under Experimental Procedures. Tissues from ten 10-week old C57BL/6 WT mice were collected and pooled for each individual experiment. cDNA derived from 640 ng of RNA was mixed with an equal volume of TaqMan gene expression 2 x master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). 100 μl-aliquots of this mixture (corresponding to 80 ng of RNA) were added to each of the 8 fill ports of a 384-well plate of a mouse GPCR array panel (Applied Biosystems). -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

6 Development of the Teeth: Root and Supporting Structures Nagat M

AVERY Chap.06 27-11-2002 10:09 Pagina 108 108 II Development of the Teeth and Supporting Structures 6 Development of the Teeth: Root and Supporting Structures Nagat M. ElNesr and James K. Avery Chapter Outline Introduction Introduction... 108 Objectives... 108 Root development is initiated through the contributions Root Sheath Development... 109 of the cells originating from the enamel organ, dental Single-Root Formation... 110 papilla, and dental follicle. The cells of the outer enamel Multiple-Root Formation... 111 epithelium contact the inner enamel epithelium at the Root Formation Anomalies... 112 base of the enamel organ, the cervical loop (Figs. 6.1 and Fate of the Epithelial Root Sheath (Hertwig's Sheath)... 113 6.2A). Later, with crown completion, the cells of the cer- Dental Follicle... 114 vical loop continue to grow away from the crown and Development of (Intermediate) Cementum... 116 become root sheath cells (Figs. 6.2B and 6.3). The inner Cellular and Acellular Cementum... 116 root sheath cells cause root formation by inducing the Development of the Periodontal Ligament... 117 adjacent cells of the dental papilla to become odonto- Development of the Alveolar Process... 119 blasts, which in turn will form root dentin. The root Summary... 121 sheath will further dictate whether the tooth will have Self-Evaluation Review... 122 single or multiple roots. The remainder of the cells of the dental papilla will then become the cells of the root pulp.The third compo- nent in root formation, the dental follicle, is the tissue that surrounds the enamel organ, the dental papilla, and the root. -

Specialized Stem Cell Niche Enables Repetitive Renewal of Alligator Teeth

Specialized stem cell niche enables repetitive renewal PNAS PLUS of alligator teeth Ping Wua, Xiaoshan Wua,b, Ting-Xin Jianga, Ruth M. Elseyc, Bradley L. Templed, Stephen J. Diverse, Travis C. Glennd, Kuo Yuanf, Min-Huey Cheng,h, Randall B. Widelitza, and Cheng-Ming Chuonga,h,i,1 aDepartment of Pathology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033; bDepartment of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Hunan 410008, China; cLouisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge, Grand Chenier, LA 70643; dEnvironmental Health Science and eDepartment of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602; fDepartment of Dentistry and iResearch Center for Wound Repair and Regeneration, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan City 70101, Taiwan; and gSchool of Dentistry and hResearch Center for Developmental Biology and Regenerative Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei 10617, Taiwan Edited by Edward M. De Robertis, Howard Hughes Medical Institute/University of California, Los Angeles, CA, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 28, 2013 (received for review July 31, 2012) Reptiles and fish have robust regenerative powers for tooth renewal. replaced from the dental lamina connected to the lingual side of However, extant mammals can either renew their teeth one time the deciduous tooth (15). Human teeth are only replaced one time; (diphyodont dentition) or not at all (monophyodont dentition). however, a remnant of the dental lamina still exists (16) and may Humans replace their milk teeth with permanent teeth and then become activated later in life to form odontogenic tumors (17). lose their ability for tooth renewal. -

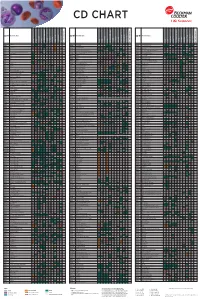

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

ADGRE1 (EMR1, F4/80) Is a Rapidly-Evolving Gene Expressed In

Edinburgh Research Explorer ADGRE1 (EMR1, F4/80) Is a Rapidly-Evolving Gene Expressed in Mammalian Monocyte-Macrophages Citation for published version: Waddell, L, Lefevre, L, Bush, S, Raper, A, Young, R, Lisowski, Z, McCulloch, M, Muriuki, C, Sauter, K, Clark, E, Irvine, KN, Pridans, C, Hope, J & Hume, D 2018, 'ADGRE1 (EMR1, F4/80) Is a Rapidly-Evolving Gene Expressed in Mammalian Monocyte-Macrophages' Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 9, 2246. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02246 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02246 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Frontiers in Immunology General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 01 October 2018 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02246 ADGRE1 (EMR1, F4/80) Is a Rapidly-Evolving Gene Expressed in Mammalian Monocyte-Macrophages Lindsey A. Waddell 1†, Lucas Lefevre 1†, Stephen J. Bush 2†, Anna Raper 1, Rachel Young 1, Zofia M. -

Basic Histology (23 Questions): Oral Histology (16 Questions

Board Question Breakdown (Anatomic Sciences section) The Anatomic Sciences portion of part I of the Dental Board exams consists of 100 test items. They are broken up into the following distribution: Gross Anatomy (50 questions): Head - 28 questions broken down in this fashion: - Oral cavity - 6 questions - Extraoral structures - 12 questions - Osteology - 6 questions - TMJ and muscles of mastication - 4 questions Neck - 5 questions Upper Limb - 3 questions Thoracic cavity - 5 questions Abdominopelvic cavity - 2 questions Neuroanatomy (CNS, ANS +) - 7 questions Basic Histology (23 questions): Ultrastructure (cell organelles) - 4 questions Basic tissues - 4 questions Bone, cartilage & joints - 3 questions Lymphatic & circulatory systems - 3 questions Endocrine system - 2 questions Respiratory system - 1 question Gastrointestinal system - 3 questions Genitouirinary systems - (reproductive & urinary) 2 questions Integument - 1 question Oral Histology (16 questions): Tooth & supporting structures - 9 questions Soft oral tissues (including dentin) - 5 questions Temporomandibular joint - 2 questions Developmental Biology (11 questions): Osteogenesis (bone formation) - 2 questions Tooth development, eruption & movement - 4 questions General embryology - 2 questions 2 National Board Part 1: Review questions for histology/oral histology (Answers follow at the end) 1. Normally most of the circulating white blood cells are a. basophilic leukocytes b. monocytes c. lymphocytes d. eosinophilic leukocytes e. neutrophilic leukocytes 2. Blood platelets are products of a. osteoclasts b. basophils c. red blood cells d. plasma cells e. megakaryocytes 3. Bacteria are frequently ingested by a. neutrophilic leukocytes b. basophilic leukocytes c. mast cells d. small lymphocytes e. fibrocytes 4. It is believed that worn out red cells are normally destroyed in the spleen by a. neutrophils b. -

Fate Map of the Dental Mesenchyme Dynamic Development Of

Developmental Biology 366 (2012) 244–254 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/developmentalbiology Fate map of the dental mesenchyme: Dynamic development of the dental papilla and follicle Michaela Rothova´ a,b,c, Renata Peterkova´ b, Abigail S. Tucker a,n a Department of Craniofacial Development, King’s College London, Floor 27 Guy’s Tower, Guy’s Hospital, London Bridge, SE1 9RT, London, UK b Department of Teratology, Institute of Experimental Medicine, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Vı´denskaˇ ´ 1083, 14220 Prague, Czech Republic c Department of Cell Biology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Vinicˇna´ 7, 128 44 Prague, Czech Republic article info abstract Article history: At the bud stage of tooth development the neural crest derived mesenchyme condenses around the Received 31 October 2011 dental epithelium. As the tooth germ develops and proceeds to the cap stage, the epithelial cervical Received in revised form loops grow and appear to wrap around the condensed mesenchyme, enclosing the cells of the forming 1 March 2012 dental papilla. We have fate mapped the dental mesenchyme, using in vitro tissue culture combined Accepted 30 March 2012 with vital cell labelling and tissue grafting, and show that the dental mesenchyme is a much more Available online 20 April 2012 dynamic population then previously suggested. At the bud stage the mesenchymal cells adjacent to the Keywords: tip of the bud form both the dental papilla and dental follicle. At the early cap stage a small population Tooth of highly proliferative mesenchymal cells in close proximity to the inner dental epithelium and primary Mouse enamel knot provide the major contribution to the dental papilla.