9780718894641 Text EH.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Income & Funding Manager

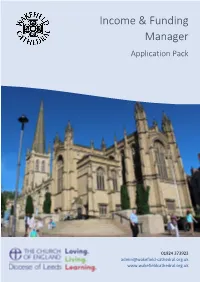

Income & Funding Manager Application Pack 01924 373923 [email protected] www.wakefieldcathedral.org.uk Application Pack – Income & Funding Manager Contents • Introduction 2 • The Cathedral 3 • The Role 3 • The Postholder 4 • Hours 4 • Annual Leave 4 • Pension 5 • Salary 5 • Probationary period 5 • Application process 5 • Job description 6 • Person specification 7 Introduction Thank you for your interest in the post of Income & Funding Manager at Wakefield Cathedral. We see this new senior role as vital to building up the capacity and sustainability of the cathedral’s ministry, and even more so as we emerge from some of the most challenging months the nation has known in peacetime for several generations. Wakefield Cathedral is not wealthy. In common with its sister cathedrals, it receives no statutory funding and is dependent on generating its own income to support its work. We are fortunate to receive discretionary funding from the Church Commissioners which covers around 30% of our current annual expenditure; the remainder is drawn from voluntary congregational giving, donations, grant applications, fundraising and income generated from events. The person appointed will undoubtedly need resilience and persistence as well as experience. They will also be joining a team of people fully committed to the flourishing of the cathedral’s ministry at the heart of the city and the wider Diocese of Leeds. I hope that the pack stimulates you to consider applying, and we look forward to hearing from you. The Very Revd Simon Cowling Dean of Wakefield Joyful – Generous – Inclusive 2 Application Pack – Income & Funding Manager The Cathedral The Cathedral stands on the site of a Saxon church in the centre of Wakefield. -

Leeds Diocesan News

Diocesan News December 2019 www.leeds.anglican.org Christmas calls Diocesan Bishop Nick Baines Secretary Advent is here and Christmas beckons. It doesn’t seem announces so long ago that we were working out how to tell the retirement Christmas story afresh, and now we have to do it again. Debbie Child, Diocesan Is there anything new to so do we today long for a Secretary for the Diocese of say? I guess the answer is resolution of our problems Leeds, is to retire from her post ‘no’ – even if we might find and struggles. But, in a funny on 31 March 2020. new ways to say the same old sort of way, Christmas offers thing. Christmas opens up for an answer that the question us, after a month of waiting of Advent did not expect. and preparing to be surprised, God did not come among us to wonder again about God, on a war horse. God didn’t the world and ourselves. If wipe out the contradictions the story has become stale, and sufferings in a single it is not the fault of the sweep of power. Rather, story, but a problem with God finds himself born in a our imagination. The birth feeding trough at the back of Jesus sees God entering of the house – subject to all Debbie has served the Diocese the real human experiences the diseases, violence and of Bradford and, latterly, Leeds and dilemmas that we face dangers any baby faced in that since 1991. as we seek to live faithfully place and at that time. -

REACHING out a Celebration of the Work of the Choir Schools’ Association

REACHING OUT A celebration of the work of the Choir Schools’ Association The Choir Schools’ Association represents 46 schools attached to cathedrals, churches and college chapels educating some 25,000 children. A further 13 cathedral foundations, who draw their choristers from local schools, hold associate membership. In total CSA members look after nearly 1700 boy and girl choristers. Some schools cater for children up to 13. Others are junior schools attached to senior schools through to 18. Many are Church of England but the Roman Catholic, Scottish and Welsh churches are all represented. Most choir schools are independent but five of the country’s finest maintained schools are CSA members. Being a chorister is a huge commitment for children and parents alike. In exchange for their singing they receive an excellent musical training and first-class academic and all-round education. They acquire self- discipline and a passion for music which stay with them for the rest of their lives. CONTENTS Introduction by Katharine, Duchess of Kent ..................................................................... 1 Opportunity for All ................................................................................................................. 2 The Scholarship Scheme ....................................................................................................... 4 CSA’s Chorister Fund ............................................................................................................. 6 Finding Choristers ................................................................................................................. -

K Eeping in T Ouch

Keeping in Touch | November 2019 | November Touch in Keeping THE CENTENARY ARRIVES Celebrating 100 years this November Keeping in Touch Contents Dean Jerry: Centenary Year Top Five 04 Bradford Cathedral Mission 06 1 Stott Hill, Cathedral Services 09 Bradford, Centenary Prayer 10 West Yorkshire, New Readers licensed 11 Mothers’ Union 12 BD1 4EH Keep on Stitching in 2020 13 Diocese of Leeds news 13 (01274) 77 77 20 EcoExtravaganza 14 [email protected] We Are The Future 16 Augustiner-Kantorei Erfurt Tour 17 Church of England News 22 Find us online: Messy Advent | Lantern Parade 23 bradfordcathedral.org Photo Gallery 24 Christmas Cards 28 StPeterBradford Singing School 35 Coffee Concert: Robert Sudall 39 BfdCathedral Bishop Nick Baines Lecture 44 Tree Planting Day 46 Mixcloud mixcloud.com/ In the Media 50 BfdCathedral What’s On: November 2019 51 Regular Events 52 Erlang bradfordcathedral. Who’s Who 54 eventbrite.com Front page photo: Philip Lickley Deadline for the December issue: Wed 27th Nov 2019. Send your content to [email protected] View an online copy at issuu.com/bfdcathedral Autumn: The seasons change here at Bradford Cathedral as Autumn makes itself known in the Close. Front Page: Scraptastic mark our Centenary with a special 100 made from recycled bottle-tops. Dean Jerry: My Top Five Centenary Events What have been your top five Well, of course, there were lots of Centenary events? I was recently other things as well: Rowan Williams, reflecting on this year and there have Bishop Nick, the Archbishop of York, been so many great moments. For Icons, The Sixteen, Bradford On what it’s worth, here are my top five, Film, John Rutter, the Conversation in no particular order. -

Music in Wells Cathedral 2016

Music in Wells Cathedral 2016 wellscathedral.org.uk Saturday 17 September 7.00pm (in the Quire) EARLY MUSIC WELLS: BACH CELLO SUITES BY CANDLELIGHT Some of the most beautiful music ever written for the cello, in the candlelit surroundings ofWells Cathedral, with one of Europe’s leading baroque cellists, Luise Buchberger (Co-Principal Cello of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment): Suites No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007; No. 4 in E-flat major, BWV 1010; and No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011 Tickets: £12.00; available from Wells Cathedral Shop Box Office and at the door Thursday 22 September 1.05 – 1.40pm (in the Quire) BACH COMPLETE ORGAN WORKS: RECITAL 11 The eleventh in the bi-monthly series of organ recitals surveying the complete organ works of J.S. Bach over six years – this year featuring the miscellaneous chorale preludes, alongside the ‘free’ organ works – played by Matthew Owens (Organist and Master of the Choristers,Wells Cathedral): Prelude in A minor, BWV 569; Kleines harmonisches Labyrinth, BWV 591; Chorale Preludes – Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier, BWV 706; Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend, BWVs 709, 726; Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 720; BWV 726; Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh’ darein, BWV 741; Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543 Admission: free Retiring collection in aid of Wells Cathedral Music Saturday 24 September 7.00pm WELLS CATHEDRAL CHOIR IN CONCERT: FAURÉ REQUIEM Wells Cathedral Choir, Jonathan Vaughn (organ),Matthew Owens (conductor) In a fundraising concert forWells Cathedral, the world-famous choir sings one of the -

Bradford Cathedral's Dean Jerry Lepine Is Setting Out

Date: 29th May 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS RELEASE BRADFORD CATHEDRAL’S DEAN JERRY LEPINE IS SETTING OUT ON A PILGRIMAGE OF PRAYER TO SISTER CATHEDRALS IN WAKEFIELD AND RIPON. The Very Revd. Jerry Lepine, Dean of Bradford, will be marking this year’s ‘Thy Kingdom Come’ by visiting and praying at the three Cathedrals in the Diocese of Leeds as part of Bradford Cathedral’s Centenary celebrations. Dean Jerry will be visiting and praying at Wakefield Cathedral on Thursday 30th May, Bradford Cathedral on Monday 3rd June and Ripon Cathedral on Wednesday 5th June, at 3pm on each day. Dean Jerry is also inviting people from the Diocese of Leeds to come and join him during this pilgrimage of prayer. The period of ‘Thy Kingdom Come’ is a global prayer movement that invites Christians around the world to pray for more people to come to know Jesus. What started in 2016 as an invitation from the Archbishops of Canterbury and York to the Church of England has grown into an international and ecumenical call to prayer. Dean Jerry says: "As part of Bradford Cathedral's Centenary I am looking forward to praying in each of the three Cathedrals in this Diocese during Thy Kingdom Come. The Archbishops have invited us to make this period of time a focus for prayer, particularly praying that people will come to faith and I look 1 HOSPITALITY. FAITHFULNESS. WHOLENESS. [email protected] Bradford Cathedral, Stott Hill, Bradford, BD1 4EH www.bradfordcathedral.org T: 01274 777720 F: 01274 777730 forward to joining with Dean John in Ripon and Dean Simon in Wakefield, and would like to invite anyone from the Diocese to join us on these occasions. -

Wakefield Cathedral: Nave and Quire Roof Repairs (1 of 3 Projects Funded) Awarded £220,000 in November 2014

Wakefield Cathedral: Nave and Quire Roof Repairs (1 of 3 projects funded) Awarded £220,000 in November 2014 The need The lead roofs of the nave and quire, installed around 1933, were leaking. The 2013 Quinquennial Inspection had highlighted a significant number of splits in the leadwork. Their condition worsened significantly over the winter of 2013-2014. Very cold weather before Christmas meant the leadwork became even more brittle and cracked further. This was then followed by the wettest period of weather over a 6- to 8-week period anybody could remember. The result was significant water penetration through the roof coverings, particularly the nave roof, necessitating buckets to collect drips within the nave, where new Work in progress on the nave roof. Photo credit: Wakefield lighting, floor and redecoration had recently been Cathedral. carried out as part of a £3 million project supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund. Emergency patching works with flashband were undertaken, during which far more splits in the lead were discovered than had been identified only a few months previously. The roof coverings needed urgent replacement if the mediaeval timber ceilings in the quire and roof bosses in the nave were not to be put at immediate risk of damage and loss. The failure of the roof coverings over such a short period of time was assessed as the most significant risk to the Cathedral’s historic fabric at the time of application. Outcomes The mediaeval timber ceilings in the quire and roof bosses in the nave are no longer at risk. Water can no longer penetrate so the new lighting, flooring and decoration are no longer threatened. -

Diocesan E-News

Diocesan e-news Events Areas Resources Welcome to the e -news for December 22 A very Happy Christmas to all our readers. This is the final E-news of the year - we will be having a short break and coming back on 12 January . Meanwhile please send your news and events to [email protected] . Spreading the news with free monthly bulletin From Easter, all churches will be able to receive free copies of the four-page printed Diocesan News Bulletin, previously only available in some areas. Fifty pick-up points are being set up and every parish can order up to 500 copies each month for no cost - but December 22 Journey of the Magi we need to hear from you soon. Find out how Springs Dance Company. 7.30pm your church can receive the bulletin here. Emmanuel Methodist, Barnsley. More. Bishop Nick responds to attack in Berlin December 22 Carols in the Pub Bishop Nick writes here in the Yorkshire Post 7pm Bay Horse, Catterick Villlage. More. in response to the attack in Berlin. Over the Christmas period you can hear December 23 Carols by Bishop Nick on Radio 4's Thought for the Day Candlelight 7.30pm, Wakefield (27 December), The Infinite Monkey Cage Cathedral. More. (9am, 27 December), Radio Leeds carol service from Leeds Minster (Dec 24 & 25, times here ) and on December 23-27 Christmas Radio York on New Year's Day (Breakfast show). Houseparty & Retreat Parcevall Hall. More. Bishop Toby sleeps out for Advent Challenge December 24 Christmas Family During Advent, young people across the Nativity 11am, Ripon Cathedral. -

Englishchurchman0422.Pdf

English Churchman Fridays, 15th & 22nd April 2005 A PROTESTANT FAMILY NEWSPAPER No.7660 Fridays, 15th &22nd April 2005 40p “PRECIOUS IN THE SIGHT OF THE LORD IS THE DEATH OF HIS SAINTS” Psalm 116:15 Italy. He understood something of the should go home rather than lecture to Ely, now in Cambridgeshire. I well self, but this Bible says "Remember "Render therefore to awfulness of war. the few that were there, but he seemed remember when the first such meeting them… who have spoken unto you the all their dues: tribute reluctant to do that. However, he ulti- at Brentwood in Essex in memory of Word of God: whose faith follow, con- to whom tribute is At the end of the war, in 1945, he felt mately agreed and I took him to the the boy martyr, William Hunter, was sidering the end of their conversation." the call to Christian ministry and railway station - he had no car in those arranged. It was in 1953, 52 years ago. due ... honour to became the pastor at the High Street days. The return fare to London at that My father was extremely interested in I described him at the start of this trib- whom honour." Baptist Church in Isleham, time was six shillings and sixpence, so I this meeting and organised for a party ute as a very dear, a very good, and a Romans 13.7 Cambridgeshire. He had some happy gave him a £1 note in the hope that of people to walk to Brentwood from very great friend. I believe he was a years there, and he particularly liked would cover his expenses. -

The Rodolfus Foundation Christmas Celebration

1 The Rodolfus Foundation Christmas Celebration THURSDAY 17th DECEMBER 2020, 6pm ORDER OF SERVICE ORGAN - ‘Es ist ein Ros’, Op. 122, No. 8 by Brahms (1833-1897) William Fairbairn is playing a virtual organ set-up (Hauptwerk) using a Dutch Schnitker organ, put through the acoustic of King’s College, Cambridge CAROL - Once in Royal David City by H J Gauntlett (1805-76) Arr. A H Mann (vs 1-3); descant David Willcocks Soloist – Charlie Trueman Rodolfus Choir Organist – Robert Scamardella at Bede’s School, Sussex. [SOLO] Once in Royal David City Stood a lowly cattle shed, Where a mother laid her baby In a manger for his bed: Mary was that mother mild, Jesus Christ her little child. PLEASE JOIN IN AT HOME! He came down to earth from heaven Who is God and Lord of all, And His shelter was a stable And His cradle was a stall; With the poor and mean and lowly Lived on earth our Saviour holy. And our eyes at last shall see Him, Through His own redeeming love; For that child so dear and gentle Is our Lord in heaven above, And He leads His children on To the place where He is gone. Not in that poor lowly stable, With the oxen standing by, We shall see Him; but in heaven, Set at God’s right hand on high; Where like stars His children crowned All in white shall wait around. 2 The Rodolfus Foundation Christmas Celebration INTRODUCTION Alexander Armstrong CAROL – God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen (Trad. arr. Willcocks) Rodolfus Choir and Friends and Family Organist – Tom Winpenny playing the organ at St Albans Cathedral. -

Diocesan E-News

Diocesan e-news Events Areas Resources Welcome to the e -news for July 6 Welcome to the latest update of news, events & resources. Click the links (picture, headline or highlighted words) for more. Contact [email protected] with your information. Our next edition is July 20. We are the Diocese - reaching out to rural communities God cares for farming communities is the message of this week's short film telling the story of life across the diocese. The focus is July 6 -30 September This is what we the Craven district of North Yorkshire where made Summer exhibition produced by St Andrew's Church, Gargrave and St Peter's Holy Trinity, Holmfirth. More. Church, Coniston Cold have been reaching out to farmers and July 7-13 A Verger's View Photo those working the land. Read more and see the film here exhibition by Jon Howard in & around Bradford Cathedral. More . Double deacon day as 20 new curates ordained Twenty men and women have been ordained July 7-10 An Ecology of Health Summer School at Holy Rood House, as deacons at services in Bradford Cathedral Thirsk. More. and will now begin their ministry as curates across the diocese. 'Welcome to life in the July 7 Sing Joyfully Madrigals to Borderlands' was the message from the Rt musicals with Aire Valley Singers. Revd John Pritchard. Read the report of the 7.30pm, St Paul's, Shipley. More. day here. July 8-9 Church of Ceylon Day Joy as 24 deacons are ordained as priests Celebrate & pray with and for our overseas link, Sri Lanka. -

![Bulletin for the Week Beginning Sunday 10 July the Seventh Sunday After Trinity [Proper 10]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3964/bulletin-for-the-week-beginning-sunday-10-july-the-seventh-sunday-after-trinity-proper-10-2903964.webp)

Bulletin for the Week Beginning Sunday 10 July the Seventh Sunday After Trinity [Proper 10]

Bulletin for the week beginning Sunday 10 July The Seventh Sunday after Trinity [Proper 10] 9.15 am Holy Communion [1662] [BCP page 167] Leeds Minster BCP Collect/Readings: Trinity VII [BCP page 167] 10.30 am The Eucharist with Hymns Leeds Minster Preacher: The Reverend Canon Sam Corley, Rector-designate 10.30 am Café Church at St Mary’s St Peter’s School LS9 7SG Family-friendly worship with Craft Activities and Prayer 6.30 pm Congregational Evensong Leeds Minster Preacher: The Reverend Canon Sam Corley, Rector-designate Leeds Minster is a Registered Charity No 1135593 Leeds Minster Office: Telephone: 0113 245 2036 Email: [email protected] Special Notice: Sunday morning Discussion Groups in St Katherine’s Chapel after 10.30 services 10.30 – THE EUCHARIST WITH HYMNS Introit Hymn: 473 [Verses 1, 6, 7 and 8] The Collect of the Day Lord of all power and might, the author and giver of all good things: graft in our hearts the love of your name, increase in us true religion, nourish us with all goodness, and of your great mercy keep us in the same; through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord, who is alive and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen. The First Reading Deuteronomy 30, 9-14 And the LORD your God will make you abundantly prosperous in all your undertakings, in the fruit of your body, in the fruit of your livestock, and in the fruit of your soil. For the LORD will again take delight in prospering you, just as he delighted in prospering your ancestors, when you obey the LORD your God by observing his commandments and decrees that are written in this book of the law, because you turn to the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul.