Why Jazz Still Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Race in the Age of Obama Making America More Competitive

american academy of arts & sciences summer 2011 www.amacad.org Bulletin vol. lxiv, no. 4 Race in the Age of Obama Gerald Early, Jeffrey B. Ferguson, Korina Jocson, and David A. Hollinger Making America More Competitive, Innovative, and Healthy Harvey V. Fineberg, Cherry A. Murray, and Charles M. Vest ALSO: Social Science and the Alternative Energy Future Philanthropy in Public Education Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences Reflections: John Lithgow Breaking the Code Around the Country Upcoming Events Induction Weekend–Cambridge September 30– Welcome Reception for New Members October 1–Induction Ceremony October 2– Symposium: American Institutions and a Civil Society Partial List of Speakers: David Souter (Supreme Court of the United States), Maj. Gen. Gregg Martin (United States Army War College), and David M. Kennedy (Stanford University) OCTOBER NOVEMBER 25th 12th Stated Meeting–Stanford Stated Meeting–Chicago in collaboration with the Chicago Humanities Perspectives on the Future of Nuclear Power Festival after Fukushima WikiLeaks and the First Amendment Introduction: Scott D. Sagan (Stanford Introduction: John A. Katzenellenbogen University) (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) Speakers: Wael Al Assad (League of Arab Speakers: Geoffrey R. Stone (University of States) and Jayantha Dhanapala (Pugwash Chicago Law School), Richard A. Posner (U.S. Conferences on Science and World Affairs) Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit), 27th Judith Miller (formerly of The New York Times), Stated Meeting–Berkeley and Gabriel Schoenfeld (Hudson Institute; Healing the Troubled American Economy Witherspoon Institute) Introduction: Robert J. Birgeneau (Univer- DECEMBER sity of California, Berkeley) 7th Speakers: Christina Romer (University of Stated Meeting–Stanford California, Berkeley) and David H. -

23Rd Annual Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference Friday, April 6, 2018 23Rd Annual Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference Friday, April 6, 2018

BASEBALL IN LITERATURE & CULTURE CONFERENCE LOGO Option 1 January 25, 2016 23rd Annual Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference Friday, April 6, 2018 23rd Annual Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference Friday, April 6, 2018 7:45 a.m. Registration and Breakfast 8:15 a.m. Welcome Andy Hazucha, Conference Coordinator Terry Haines, Ottawa University Provost 8:30 — Morning Keynote Address 9:15 a.m. Morning Keynote Speaker: Gerald Early 9:30 — Concurrent Sessions A 10:30 a.m. Session A1: Baseball in Popular Culture Location: Hasty Conference Room Chair: Shannon Dyer, Ottawa University • Eric Berg, MacMurray College: “When 1858 and 2018 Meet on the Field: Integrating the Modern Game into Vintage Base Ball” • Melissa Booker, Independent Scholar: “Baseball: The Original Social Network” • Nicholas X. Bush, Motlow State Community College: “Seams and Sestets: A Poetic Examination of Baseball Art and Culture” Session A2: Baseball History Location: Goppert Conference Room Chair: Bill Towns, Ottawa University • Mark Eberle, Fort Hays State University: “Dwight Eisenhower’s Baseball Career” • Jan Johnson, Independent Scholar: “Cartooning the Home Team” • Gerald C. Wood, Carson-Newman University: “The 1926-27 Baseball Scandal: What Happened and Why We Should Care” Session A3: From the Topps: Using Baseball Cards as Creative Inspiration (a round table discussion) Location: Zook Conference Room Chair: George Eshnaur, Ottawa University • Andrew Jones, University of Dubuque • Matt Muilenburg, University of Dubuque • Casey Pycior, University of Southern Indiana 10:45 — Concurrent Sessions B 11:45 a.m. Session B: The State of the Game (a conversation about baseball’s present and future) Location: Hasty Conference Room Chair: Greg Echlin, Kansas Public Radio and KCUR-FM • Gerald Early, Morning Keynote Speaker • Bill James, 2016 Morning Keynote Speaker • Dee Jackson, Sports Reporter for KSHB-TV, Kansas City 12:00 — Luncheon and Afternoon Keynote Speaker 1:30 p.m. -

New Books 8-03

New Books 8-03 New Titles for August 2003 Following is a list of new titles added to the State Library collection during August of 2003. Entries are arranged in classified order, according to the Dewey Decimal Classification's ten main classes, with the addition of a few categories of local interest. This month, for the first time, we are including our new audiovisual titles. As of July, 2003, Louisiana State documents are no longer included. Lists of newly-acquired state publications are posted on the Recorder of Documents site. For information on how you may borrow these and other titles, please consult Borrowing Materials on the Library’s home page. 300 Social Sciences Louisiana Titles 400 Language Large Print 500 Natural Sciences & Mathematics Audiovisuals 600 Technology (Applied Sciences) 000 Generalities/Computing 700 The Arts (Fine & Decorative Arts) 100 Philosophy & Psychology 800 Literature & Rhetoric 200 Religion 900 Geography & History Generalities/Computing Monsters : evil beings, mythical beasts, and all manner of imaginary terrors / David D. Gilmore. Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, c2003. 001.944 Gil 2003 Sams teach yourself C++ in 21 days / Jesse Liberty. Indianapolis, IN : Sams, c2001. DISK 005.133 Lib 2001 Sams teach yourself Red Hat Linux 8 in 24 hours / Aron Hsiao. Indianpolis : Sams, c2003. DISK 005.4469 Hsi 2003 CoursePrep examguide/studyguide MCSE exam 70-270 : installing, configuring, and administering Microsoft Windows XP Professional / [James Michael Stewart]. Boston, Mass. : Course Technology/Thomson Learning, c2002. 005.4469 Ste 2002 Essential blogging / Cory Doctorow ... [et al.]. Sebastopol, Calif. : O'Reilly, c2002. 005.72 Ess 2002 Information architecture for the World Wide Web / Louis Rosenfeld and Peter Morville. -

9781883982386 #Gerald Lyn Early #228 Pages #Missouri History Museum, 2001 #2001 #Miles Davis and American Culture

9781883982386 #Gerald Lyn Early #228 pages #Missouri History Museum, 2001 #2001 #Miles Davis and American Culture Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926 â“ September 28, 1991) was an American jazz musician, trumpeter, bandleader, and composer. Widely considered one of the most influential and innovative musicians of the 20th century,[1] Miles Davis was, together with his musical groups, at the forefront of several major developments in jazz music, including bebop, cool jazz, hard bop, modal jazz, post-bop and jazz fusion. Miles Davis and the 1960s avant-garde Waldo E. Martin Jr. From Kind of blue to Bitches brew Quincy Troupe. "It's about that time": the response to Miles Davis's electric turn Eric Porter. Miles Davis and the double audience Martha Bayless. "Here's God walking around" An interview with Joey DeFrancesco. Ladies sing Miles Farah Jasmine Griffin. Miles Davis and American culture. Web link. Early, Gerald Lyn. Miles Davis and American culture. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2001. WildCat. Another Article I found âœMiles Davis's unfinished electric revolutionâ tells another way Miles Davis was able to change jazz music. His introduction of electric instruments and his popular and new structures to his music. He was able to bring a âœjazz-rock fusionâ to the table which was new to everyone. This changed the way jazzed was played since. Posted by Robbie at 4:30 PM No comments: One article I found was âœA sense of the possible: Miles Davis and the semiotics of improvised performance. (jazz musician)(includes bibliography).â This article really showed me what Miles Davis that did Gerald Lyn Early (born April 21, 1952) is an American essayist and American culture critic. -

Kalamazoo College Academic Catalog

KALAMAZOO COLLEGE 2021-2022 ACADEMIC CATALOG Shared Passages The Shared Passages Program is a curricular thread that integrates features of the K-Plan. Required in the first, sophomore, and senior years, Shared Passages courses provide a developmental, pedagogical, and intellectual arc to the liberal arts experience and create a "backbone" to an effective, flexible liberal arts education in which the whole is greater than the sum of its component parts. First-Year Seminars First-Year Seminars constitute the gateway to the K-Plan and to college life for entering students and serve as the foundation of the Shared Passages Program. Offered in the fall quarter, these Seminars are designed to orient students to college-level learning practices, with particular emphasis on critical thinking, writing, speaking, information literacy, and intercultural engagement. First-Year seminars SEMN 101 FYS: Dissent: Sites of Protest and Resistance Dissent, in its different forms, has shaped history and continues to claim ground for theory and action, in increasingly urgent ways, in the digital age. New technologies of surveillance, discrimination, and oppression emerge and digitally enabled injustices and forms of violence and inequality, (re-) appear often continuing past legacies of colonialism and exploitation. At the same time, new sites and platforms for subversive voices and practices are created and imagined in response. In this course, we will map these forms and spaces of oppression, violence, and inequality, but also the emerging sites of protest, resistance, and disobedience. In doing so we will think about the condition - as both a mode of thinking and praxis- of being a dissident and its new dangers and possibilities in our globalized world. -

ISBN TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER/MMEDIUM AREA SHELF LOCATION QUANT 9780761453482 Born for Adventure Kathleen Karr Two Lions Hardcover

ISBN TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER/MMEDIUM AREA SHELF LOCATION QUANT 9780761453482 Born for Adventure Kathleen Karr Two Lions Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780374371784 Time's Memory Julius Lester Farrar Straus GHardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 At the Crossroads Rachel Isadora Greenwillow Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780517885444 Tar Beach Faith Ringgold Dragonfly BooPaperback Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 Never Forgotten Patricia McKissack Schwartz and Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9781563978227 Madoulina (Story from West Africa) Joe Bognomo Boyds Mills PrPaperback Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780374312893 Circle Unbroken Margot Theis Raven Farrar, Straus Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780688102562 African Beginnings Kathleen Benson; James Haskins Amistad Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780688151782 Storytellers, The Ted Lewin Harpercollins Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780027814903 Abiyoyo Pete Seeger Simon and SchHardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780671882686 Fire on the Mountain Earl B. Lewis Simon & SchuHardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780690013344 Honey, I Love and Other Love Poems Eloise Greenfield HarperCollins Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780545270137 One Hen: How One Small Load Made a Big Difference Katie Smith Milway Scholastic Paperback Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 2 Man of the People: A Novel -

Unveiling Christian Motifs in Select Writers of Harlem Renaissance Literature

UNVEILING CHRISTIAN MOTIFS IN SELECT WRITERS OF HARLEM RENAISSANCE LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Professional Studies by Joycelyn Laverne Collins May 2007 © 2007 Joycelyn Laverne Collins ABSTRACT Prior to the early 1900s, much of the artistic expression of African American writers and artists was strongly steeped in a Christian tradition. With the Harlem Renaissance (roughly 1917-1934), the paradigm shifted to some degree. An examination of several books and articles written during and about the Harlem Renaissance revealed that very few emphasized religion as a major theme of influence on Renaissance artists. This would suggest that African American intelligentsia in the first three decades of the twentieth century were free of the strong ties to church and Christianity that had been a lifeline to so many for so long. However, this writer suggests that, as part of an African American community deeply rooted in Christianity, writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance period must have had some roots in and expression of that same experience. The major focus of this research, therefore, is to discover and document the extent to which Christianity influenced the Harlem Renaissance. The research is intended to answer the following questions concerning the relationship of Christianity to the Harlem Renaissance: 1. What was the historical and religious context of the Harlem Renaissance? 2. To what extent did Christianity influence the writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance? 3. Did the tone of their artistry change greatly from the previous century? If so, what were the catalysts? 4. -

Arturo O'farrill Ron Horton Steve Potts Stan Getz

SEPTEMBER 2015—ISSUE 161 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM GARY BARTZ musical warrior ARTURO RON STEVE STAN O’FARRILL HORTON POTTS GETZ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East SEPTEMBER 2015—ISSUE 161 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Arturo O’Farrill 6 by russ musto [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Ron Horton 7 by sean fitzell General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Gary Bartz 8 by james pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Steve Potts by clifford Allen Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Stan Getz 10 by george kanzler [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : 482 Music by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above or email [email protected] Festival Report 13 Staff Writers David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, CD Reviews 14 Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Katie Bull, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Miscellany 39 Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Event Calendar Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, 40 Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Alto saxophonist Gary Bartz (On The Cover) turns 75 this month and celebrates with two nights at Dizzy’s Club. -

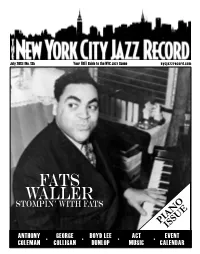

Stompin' with Fats

July 2013 | No. 135 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com FATS WALLER Stompin’ with fats O N E IA U P S IS ANTHONY • GEORGE • BOYD LEE • ACT • EVENT COLEMAN COLLIGAN DUNLOP MUSIC CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK FEATURED ARTISTS / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 RESIDENCIES / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 Mondays July 1, 15, 29 Friday & Saturday July 5 & 6 Wednesday July 3 Jason marshall Big Band Papa John DeFrancesco Buster Williams sextet Mondays July 8, 22 Jean Baylor (vox) • Mark Gross (sax) • Paul Bollenback (g) • George Colligan (p) • Lenny White (dr) Wednesday July 10 Captain Black Big Band Brian Charette sextet Tuesdays July 2, 9, 23, 30 Friday & Saturday July 12 & 13 mike leDonne Groover Quartet Wednesday July 17 Eric Alexander (sax) • Peter Bernstein (g) • Joe Farnsworth (dr) eriC alexaNder QuiNtet Pucho & his latin soul Brothers Jim Rotondi (tp) • Harold Mabern (p) • John Webber (b) Thursdays July 4, 11, 18, 25 Joe Farnsworth (dr) Wednesday July 24 Gregory Generet George Burton Quartet Sundays July 7, 28 Friday & Saturday July 19 & 20 saron Crenshaw Band BruCe Barth Quartet Wednesday July 31 Steve Nelson (vibes) teri roiger Quintet LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES Mon the smoke Jam session Friday & Saturday July 26 & 27 Sunday July 14 JavoN JaCksoN Quartet milton suggs sextet Tue milton suggs Quartet Wed Brianna thomas Quartet Orrin Evans (p) • Santi DeBriano (b) • Jonathan Barber (dr) Sunday July 21 Cynthia holiday Thr Nickel and Dime oPs Friday & Saturday August 2 & 3 Fri Patience higgins Quartet mark Gross QuiNtet Sundays Sat Johnny o’Neal & Friends Jazz Brunch Sun roxy Coss Quartet With vocalist annette st.