Version of Record with a CC BY-NC-SA Licence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

A Closer Look at Argus Books' 1930 the Lives of the Twelve Caesars

In the Spirit of Suetonius: A Closer Look at Argus Books’ 1930 The Lives of the Twelve Caesars Gretchen Elise Wright Trinity College of Arts and Sciences Duke University 13 April 2020 An honors thesis submitted to the Duke Classical Studies Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with distinction for a Bachelor of Arts in Classical Civilizations. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 2 Introduction 3 Chapter I. The Publisher and the Book 7 Chapter II. The Translator and Her “Translation” 24 Chapter III. “Mr. Papé’s Masterpiece” 40 Conclusion 60 Illustrations 64 Works Cited 72 Other Consulted Works 76 Wright 1 Acknowledgements First and foremost, this project would never have existed without the vision and brilliance of Professor Boatwright. I would like to say thank you for her unwavering encouragement, advice, answers, and laughter, and for always making me consider: What would Agrippina do? A thousand more thanks to all the other teachers from whom I have had the honor and joy of learning, at Duke and beyond. I am so grateful for your wisdom and kindness over the years and feel lucky to graduate having been taught by all of you. My research would have been incomplete without the assistance of the special collections libraries and librarians I turned to in the past year. Thank you to the librarians at the Beinecke and Vatican Film Libraries, and of course, to everyone in the Duke Libraries. I could not have done this without you! I should note that I am writing these final pages not in Perkins Library or my campus dormitory, but in self-isolation in my childhood bedroom. -

The Loneliest Road

THE BOOKS Sunday, May 3, 2009 Presented by The Empty Bottle with the MCA mcachicago.org THE EmptY BottLE WITH THE MCA PResents THE BooKS All photos of The Books courtesy of the artists Original music composed by Nick Zammuto and Paul de Jong Performed by Nick Zammuto and Paul de Jong For more information about The Empty Bottle and a schedule of upcoming events, visit emptybottle.com. ARTISTS UP CLOSE 5 To increase appreciation of The Books, the MCA, and Third Coast International Audio Festival organized this additional opportunity earlier today for audience mem- bers to engage with the artists. Sunday, May 3, 4–6 pm cast Third Coast Festival Listening Room Karen Lee as Candy Mintz The Loneliest Road Thom Whaley as Terry Trenton Written and directed by Gregory Whitehead Je= Kent as the Post-Mortem Narrator Original music by The Books Cynthia Atwood as Una Jon Swan as Ted Stebbins This 90-minute audio drama, produced by sound Daniel Klein as Stu Berkowitz artist and storyteller Gregory Whitehead with The Gregory Whitehead as Oswald Norris Books, is best experienced as a pirate radio broad- Anne Undeland as Ava Ravenella cast from the obstructed heartland of the American Dream. Haunted by dead poets, Marilyn Monroe, Original music composed by Paul de Jong and and an angel’s solemn whisper, the drama unfolds Nick Zammuto, and performed by Paul de Jong, through layers of Whitehead’s signature humor, Nick Zammuto, Anne Doerner, and sonic playfulness, and astute observations about Gregory Whitehead human triumph and folly. The Loneliest Road was originally commissioned for BBC Radio 3 and won the Sony Gold Award for Radio Drama in 2004. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/222 - Total : 8629 Vinyls Au 05/10/2021 Collection "Artistes Divers Toutes Catã©Gorie

Collection "Artistes divers toutes catégorie. TOUT FORMATS." de yvinyl Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage !!! !!! LP GSL39 Etats Unis Amerique 10cc Windows In The Jungle LP MERL 28 Royaume-Uni 10cc The Original Soundtrack LP 9102 500 France 10cc Ten Out Of 10 LP 6359 048 France 10cc Look Hear? LP 6310 507 Allemagne 10cc Live And Let Live 2LP 6641 698 Royaume-Uni 10cc How Dare You! LP 9102.501 France 10cc Deceptive Bends LP 9102 502 France 10cc Bloody Tourists LP 9102 503 France 12°5 12°5 LP BAL 13015 France 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic Sounds LP LIKP 003 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Live LP LIKP 002 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Easter Everywhere LP IA 5 Etats Unis Amerique 18 Karat Gold All-bumm LP UAS 29 559 1 Allemagne 20/20 20/20 LP 83898 Pays-Bas 20th Century Steel Band Yellow Bird Is Dead LP UAS 29980 France 3 Hur-el Hürel Arsivi LP 002 Inconnu 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys LP 64835 Pays-Bas 38 Special W.w. Rockin' Into The Night LP 64782 Pays-Bas 38 Special Tour De Force LP SP 4971 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Strength In Numbers LP SP 5115 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Special Forces LP 64888 Pays-Bas 38 Special Special Delivery LP SP-3165 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Rock & Roll Strategy LP SP 5218 Etats Unis Amerique 45s (the) 45s CD hag 009 Inconnu A Cid Symphony Ernie Fischbach And Charles Ew...3LP AK 090/3 Italie A Euphonius Wail A Euphonius Wail LP KS-3668 Etats Unis Amerique A Foot In Coldwater Or All Around Us LP 7E-1025 Etats Unis Amerique A's (the A's) The A's LP AB 4238 Etats Unis Amerique A.b. -

Sonification As a Means to Generative Music Ian Baxter

Sonification as a means to generative music By: Ian Baxter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts & Humanities Department of Music January 2020 Abstract This thesis examines the use of sonification (the transformation of non-musical data into sound) as a means of creating generative music (algorithmic music which is evolving in real time and is of potentially infinite length). It consists of a portfolio of ten works where the possibilities of sonification as a strategy for creating generative works is examined. As well as exploring the viability of sonification as a compositional strategy toward infinite work, each work in the portfolio aims to explore the notion of how artistic coherency between data and resulting sound is achieved – rejecting the notion that sonification for artistic means leads to the arbitrary linking of data and sound. In the accompanying written commentary the definitions of sonification and generative music are considered, as both are somewhat contested terms requiring operationalisation to correctly contextualise my own work. Having arrived at these definitions each work in the portfolio is documented. For each work, the genesis of the work is considered, the technical composition and operation of the piece (a series of tutorial videos showing each work in operation supplements this section) and finally its position in the portfolio as a whole and relation to the research question is evaluated. The body of work is considered as a whole in relation to the notion of artistic coherency. This is separated into two main themes: the relationship between the underlying nature of the data and the compositional scheme and the coherency between the data and the soundworld generated by each piece. -

Interview with MO Just Say

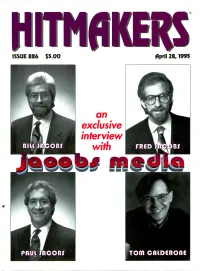

ISSUE 886 $5.00 flpril 28, 1995 an exclusive interview with MO Just Say... VEDA "I Saw You Dancing" GOING FOR AIRPLAY NOW Written and Produced by Jonas Berggren of Ace OF Base 132 BDS DETECTIONS! SPINNING IN THE FIRST WEEK! WJJS 19x KBFM 30x KLRZ 33x WWCK 22x © 1995 Mega Scandinavia, Denmark It means "cheers!" in welsh! ISLAND TOP40 Ra d io Multi -Format Picks Based on this week's EXCLUSIVE HITMEKERS CONFERENCE CELLS and ONE-ON-ONE calls. ALL PICKS ARE LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER. MAINSTREAM 4 P.M. Lay Down Your Love (ISLAND) JULIANA HATFIELD Universal Heartbeat (ATLANTIC) ADAM ANT Wonderful (CAPITOL) MATTHEW SWEET Sick Of Myself (ZOO) ADINA HOWARD Freak Like Me (EASTWEST/EEG) MONTELL JORDAN This Is How...(PMP/RAL/ISLAND) BOYZ II MEN Water Runs Dry (MOTOWN) M -PEOPLE Open Up Your Heart (EPIC) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Secret Garden (COLUMBIA) NICKI FRENCH Total Eclipse Of The Heart (CRITIQUE) COLLECTIVE SOUL December (ATLANTIC) R.E.M. Strange Currencies (WARNER BROS.) CORONA Baby Baby (EASTWEST/EEG) SHAW BLADES I'll Always Be With You (WARNER BROS.) DAVE MATTHEWS What Would You Say (RCA) SIMPLE MINDS Hypnotised (VIRGIN) DAVE STEWART Jealousy (EASTWEST/EEG) TECHNOTRONIC Move It To The Rhythm (EMI RECORDS) DIANA KING Shy Guy (WORK GROUP) ELASTICA Connection (GEFFEN) THE JAYHAWKS Blue (AMERICAN) GENERAL PUBLIC Rainy Days (EPIC) TOM PETTY It's Good To Be King (WARNER BRCS.) JON B. AND BABYFACE Someone To Love (YAB YUM/550) VANESSA WILLIAMS The Way That You Love (MERCURY) STREET SHEET 2PAC Dear Mama INTERSCOPE) METHOD MAN/MARY J. BIJGE I'll Be There -

Common Tape Manipulation Techniques and How They Relate to Modern Electronic Music

Common Tape Manipulation Techniques and How They Relate to Modern Electronic Music Matthew A. Bardin Experimental Music & Digital Media Center for Computation & Technology Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803 [email protected] ABSTRACT the 'play head' was utilized to reverse the process and gen- The purpose of this paper is to provide a historical context erate the output's audio signal [8]. Looking at figure 1, from to some of the common schools of thought in regards to museumofmagneticsoundrecording.org (Accessed: 03/20/2020), tape composition present in the later half of the 20th cen- the locations of the heads can be noticed beneath the rect- tury. Following this, the author then discusses a variety of angular protective cover showing the machine's model in the more common techniques utilized to create these and the middle of the hardware. Previous to the development other styles of music in detail as well as provides examples of the reel-to-reel machine, electronic music was only achiev- of various tracks in order to show each technique in process. able through live performances on instruments such as the In the following sections, the author then discusses some of Theremin and other early predecessors to the modern syn- the limitations of tape composition technologies and prac- thesizer. [11, p. 173] tices. Finally, the author puts the concepts discussed into a modern historical context by comparing the aspects of tape composition of the 20th century discussed previous to the composition done in Digital Audio recording and manipu- lation practices of the 21st century. Author Keywords tape, manipulation, history, hardware, software, music, ex- amples, analog, digital 1. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

Applied Tape Techniques for Use with Electronic Music Synthesizers. Robert Bruce Greenleaf Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1974 Applied Tape Techniques for Use With Electronic Music Synthesizers. Robert Bruce Greenleaf Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Greenleaf, Robert Bruce, "Applied Tape Techniques for Use With Electronic Music Synthesizers." (1974). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8157. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8157 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A p p l ie d tape techniques for use with ELECTRONIC MUSIC SYNTHESIZERS/ A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Doctor of Musical Arts In The School of Music by Robert Bruce Greenleaf M.M., Louisiana State University, 1972 A ugust, 19714- UMI Number: DP69544 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69544 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

PF21-0466F.Pdf

TACOMA VENUES & EVENTS REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL MANAGEMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS VENUES SPECIFICATION NO. PF21-0466F PF21-0466F Page 1 of 101 PF21-0466F Page 2 of 101 City of Tacoma Tacoma Venues and Events REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS PF21-0466F Management of Performing Arts Venues Submittal Deadline: 11:00 a.m., Pacific Time, Tuesday, May 11, 2021 Submittal Delivery: Sealed submittals will be received as follows: By Email: [email protected] Maximum file size: 35 MB. Multiple emails may be sent for each submittal. Bid Opening: Held virtually each Tuesday at 11AM. Attend via this link or call 1 (253) 215 8782. Submittals in response to a RFP will be recorded as received. As soon as possible, after 1:00 PM, on the day of submittal deadline, preliminary results will be posted to www.TacomaPurchasing.org. Solicitation Documents: An electronic copy of the complete solicitation documents may be viewed and obtained by accessing the City of Tacoma Purchasing website at www.TacomaPurchasing.org. • Register for the Bid Holders List to receive notices of addenda, questions and answers and related updates. • Click here to see a list of vendors registered for this solicitation. Pre-Proposal Meeting: A pre-proposal meeting will be held at 9 am on April 16, 2021. See Section 7.2 of the specification for a link to RSVP for this meeting. Project Scope: The City of Tacoma is seeking proposals for the management and operations of its Performing Arts Venues. Paid Sick Leave: The City of Tacoma requires all employers to provide paid sick leave as set forth in Title 18 of the Tacoma Municipal Code. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Book Review with TTU Libraries Cover Page

BOOK REVIEW: BEYOND AND BEFORE: THE FORMATIVE YEARS OF YES BY PETER BANKS The Texas Tech community has made this publication openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters to us. Citation Weiner, R.G. (2008). [Review of the book Beyond and Before: The Formative Years of Yes by Peter Banks]. Popular Music and Society, 31(1), 136-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007769908591748 Citable Link http://hdl.handle.net/2346/1546 Terms of Use CC-BY Title page template design credit to Harvard DASH. 136 Book Reviews Hammond’s myopic vision, his unrelenting determination, and his deep personal sorrows, but to his friends and supporters Hammond was a trying project. Perhaps, as Prial suggests, Hammond’s relationship to the Vanderbilts did him more good in his early years in music than his social skills. There are questions unanswered and undeveloped in this biography related to Hammond the man, such as his falling out with Aretha Franklin or his quick parting with Dylan. Each chapter of this book comes (another assault on your pocketbook) with a wonderful ‘‘discography’’ that should slow down the pace of reading but will contribute to a great start in building a library of American music of the 20th century. It is quite something how much music Hammond had a role in, and this portion of the book is an important reminder of the times and genres Hammond touched. As with all biographies there are problems and limitations. For those of us raised in the second half of the century, The Producer fails to deliver the same magic surrounding the discovery and signing of ‘‘our’’ heroes as it does around the early stars.