An Even Chance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

Sensesational Storytime Manual

SENSESATIONAL STORYTIME MANUAL A handbook containing storytime planning cards including songs, rhymes, group activities, sensory exploration, and crafts appropriate for children with sensory/special needs. SENSORY STORYTIME MANUAL AUTHORS Carolyn Brooks Branch Manager, El Dorado Hills Library Debbie Arenas Early Childhood Literacy Specialist, El Dorado Hills Library Geneva Paulson Early Childhood Literacy Specialist, Placerville Library Robyn Chu MOT, OTR/L Growing Healthy Children Therapy Services TYPING & LAYOUT Kathryn McGinness El Dorado County Library SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to acknowledge and thank Betsy Diamant-Cohen and her storytime program, Mother Goose on the Loose, for inspiring us to provide excellent service to the youngest members of our community. A tremendous thank you to Kathi Guerrero and First 5 of El Dorado for all of their support for our community’s children. PRINTING Copyright© 2014 by the El Dorado County Library. Permission is granted to print and reproduce the contents of this manual for personal, educational, and non-commercial use. This project was funded, in part or whole, by a federal IMLS grant, administered by the California State Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA). ii To the families of El Dorado County who read to their children each and every day TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Carolyn Brooks…………………........................…...5 Chapter 1: Background & Research Introduction.............................................................................................7 What is Sensory -

Raising Children with Roots, Rights & Responsibilities

Raising Children With Roots, Rights & Responsibilities: Celebrating the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Written by Lori DuPont, Joanne Foley, and Annette Gagliardi Founders of the Circle for the Child Project Edited and designed by Julie Penshorn, Co-Director, Growing Communities for Peace Published by University of Minnesota Human Rights Resource Center and the Stanley Foundation Copyright © 1999 Human Rights Resource Center, University of Minnesota The Human Rights Education Series is published by the Human Rights Resource Center at the University of Minnesota and the Stanley Foundation. The series provides resources for the ever-growing body of educators and activists working to build a culture of human rights in the United States and throughout the world. Raising Children with Roots, Rights, & Responsibilities: Celebrating the Convention on the Rights of the Child may be reproduced without permission for educational use only. No reproductions may be sold for profit. Excerpted or adapted material from this publication must include full citation of the source. To reproduce for any other purposes, a written request must be submitted to the Human Rights Resource Center. The Human Rights Education Series is edited by Nancy Flowers. Edited and designed by Julie Penshorn, Co-Director of Growing Communities for Peace. Illustrations by eleven-year-old Margaret Anne Gagliardi. Cover design donated by Nancy Hope. ISBN 0-9675334-1-3 To order further copies of Raising Children With Roots, Rights, & Responsibilities: Celebrating the Conven- tion on the Rights of the Child, contact: Human Rights Resource Center University of Minnesota 229 - 19th Avenue South, Room 439 Minneapolis, MN 55455 Tel: 1-888-HREDUC8 Fax: 612-625-2011 email: [email protected] http://www.hrusa.org and http://www.umn.edu/humanrts A contribution to the United Nations Decade for Human Rights Education, 1995-2004 Dedication This book is lovingly dedicated to our children: Jesse, Jacob, Rachel, Erica, Marian, Maggie, and Maria and to the children of the world. -

Dealing with Death

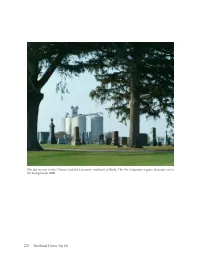

The old section of the Clinton-Garfield Cemetery southeast of Rolfe. The Pro Cooperative grain elevators are in the background. 2000. 270 The Road I Grew Up On DEALING WITH DEATH A Day of Mourning Don Grant died on September 29, 2001. I had visited him on Thursday, September 13, two days after the World Trade Center and Pentagon were attacked on September 11. Then on the national day of mourning on Friday, September 14, I wrote an essay in response to the events of the week. It included the following portion that begins with reference to a photo excursion I had taken with a friend, Janis Pyle. She wanted me to bring my camera and help her document farms and other places of her rural heritage in central Iowa. It was on that outing that I saw Don for the last time. Janis and I talked about the attacks on New York and Washington and how people would be quick to retaliate rather than understand that the best form of national defense is to share power and resources more equitably in the world. Janis and I also talked at length about rural and small-town life and how the agricultural economy is in really bad shape. It is hard for some people to realize how bad things are because the tragedy of the farm scene doesn’t have the kind of visual impact for television as airliners hitting the Twin Towers and the subsequent collapse of those icons of American prosperity. The farms we visited were like so many around the Rolfe area, vastly different than when they thrived with activity in past decades. -

Summerhill Is the Most Unusual School in the World. Here's a Place Where

Summerhill is the most unusual school in the world. Here’s a place where children are not compelled to go to class – they can stay away from lessons for years, if they want to. Yet, strangely enough, the boys and girls in this school LEARN! In fact, being deprived of lessons turns out to be a severe punishment. Summerhill has been run by A. S . Neill for almost forty years. This is the world’s greatest experiment in bestowing unstinted love and approval on children. This is the place, where one courageous man, backed by courageous parents, has had the fortitude to actually apply – without reservation – the principles of freedom and non- repression. The school runs under a true children’s government where the “bosses” are the children themselves. Despite the common belief that such an atmosphere would create a gang of unbridled brats, visitors to Summerhill are struck by the self-imposed discipline of the pupils, by their joyousness, the good manners. These kids exhibit a warmth and lack of suspicion toward adults, which is the wonder, and delight of even official British school investigators. In this book A. S. Neill candidly expresses his unique - and radical – opinions on the important aspects of parenthood and child rearing. These strong commendations of authors and educators attest that every parent who reads this book will find in it many examples of how Neill’s philosophy may be applied to daily life situations. Educators will find Neill’s refreshing viewpoints practical and inspiring. Reading this book is an exceptionally gratifying experience, for it puts into words the deepest feelings of all who care about children, and wish to help them lead happy, fruitful lives. -

A Film by FRANÇOIS TROUKENS & JEAN-FRANÇOIS HENSGENS

VERSUS PRODUCTION PRESENTS ABOVE THE LAW A film by FRANÇOIS TROUKENS & JEAN-FRANÇOIS HENSGENS SYNOPSIS A film by François Troukens & Jean-François Hensgens ABOVE THE LAW TUEURS With OLIVIER GOURMET - LUBNA AZABAL - KEVIN JANSSENS - BOULI LANNERS TIBO VANDENBORRE - BÉRÉNICE BAOO - KARIM BARRAS & with the participation of NATACHA RÉGNIER - ANNE COESENS - JOHAN LEYSEN 86’ – IMAGE: SCOPE 2.39 – SOUND: 5.1 BELGIUM / FRANCE – FRENCH LANGUAGE – 2017 INTERNATIONAL PR hile Frank Valken is carrying out a daring but non-violent hold-up, a commando force steps in and kills an examining magistrate BARBARA VAN LOMBEEK - [email protected] +32 486 54 64 80 investigating a political case. Charged thanks to rigged evidence, Frank is arrested. In the face of the media pressure, the INTERNATIONAL SALES gangster has no other choice but to escape and attempt to prove his innocence. TF1 INTERNATIONAL STUDIO - [email protected] +33 1 41 41 21 68 W As a child, I lived a couple hundred meters away from a supermarket Destiny has brought me to run into a series of people who’ve been in the suburbs of Brussels. My brother and I used to like to dress up as linked in different ways to these cases. While in prison, a part from beggars and play music near the store entrance. gangsters, I met ex-policemen, magistrates, and even a few ministers. On a September day in 1985, three masked killers shot and killed Characters that I could draw my inspiration from and that led me to FRANCOIS TROUKENS’ anyone the came across. Women, children, elderly people… A dozen bring them to life in this contemporary fiction. -

UGC Présente

UGC presents a Page 114 and Why Not Productions production Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND BONE A film by Jacques Audiard Armand Verdure Céline Sallette Corinne Masiero Bouli Lanners Jean-Michel Correia Winner, Best Film BFI London Festival, 2012 Official Selection Cannes Film Festival 2012 Toronto International Film Festival 2012 Telluride Film Festival 2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Jeff Hill Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics [email protected] Alexandra Glazer Carmelo Pirrone +1 917-575-8808 Ziggy Kozlowski Alison Farber 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 1 SYNOPSIS ALI (Matthias Schoenaerts) finds himself with a five-year-old child on his hands. SAM (Armand Verdure) is his son, but he hardly knows him. Homeless, penniless and friendless, Ali takes refuge with his sister ANNA (Corinne Masiero) in Antibes, in the south of France. There things improve immediately. She puts them up in her garage, she takes the child under her wing and the weather is glorious. Ali, a man of formidable size and strength, gets a job as a bouncer in a nightclub. He comes to the aid of STEPHANIE (Marion Cotillard) during a nightclub brawl. Aloof and beautiful, Stéphanie seems unattainable, but in his frank manner Ali leaves her his phone number anyway. Stephanie trains orca whales at Marineland. When a performance ends in tragedy, a call in the night again brings them togtether. When Ali sees her next, Stephanie is confined to a wheel chair : she has lost her legs and quite a few illusions. -

Youth Activities Guidebullhead City's 2017 Spr Ing & Summer Edition

youth activities Guide Bullhead City’s 2017 Spring & Summer Edition MOHAVE ACCELERATED SCHOOLS EMPOWERING FUTURE LEADERS FOR SUCCESS As the top-rated schools in our community*, we offer a quality education and so much more... With sports, clubs, music programs and other great extracurricular activities, our students enjoy a diverse and well-rounded school experience. But its not just what’s happening after school... Our certiÞed, highly qualiÞed teachers are helping students earn the best state test scores in the area! CHARTER IS CHOICE! 625 Marina Blvd. (928) 758-MALC PATRIOTS www.mohavelearning.org Is a charter school right for you? Don’t be fooled by our size... We offer the same opportunities found in much larger schools with the ßexibility and creativity that can’t be matched by anyone! Class sizes are limited and tuition is free. The decision is yours! * According to the annual rankings provided by the AZ Dept. of Education 2 www.bullheadcity.com 2017 Youth Activities Guide Spring & Summer Edition Youth Guide Page Index Art & Music . 5-6 Youth Clubs . 12-15 Entertainment . 20-21 Community Pool . .26-27 Local Events . 28-33 Shout Outs! . 36-37 Family Resources . 40-43 Youth Sports . 45-47 2017 Youth Activities Guide Spring & Summer Edition www.bullheadcity.com | 3 YOUTH ACTIVITIES guIDE 2017 SPRING & SUMMER EDITION PRODUCED BY: CITY OF BULLHEAD CITY PARKS & RECREATION DEPARTMENT LOCATED AT 2355 TRANE ROAD BULLHEAD CITY, AZ 86442 Dave HEath Recreation Manager PHONE NUMBER (928) 763-9400 EXT.148 WEBSITE WWW.BULLHEADCITY.COM EMAIL [email protected] -

Books (ON) Reports Research/Technical (143)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 387 236 PS 023 578 AUTHOR Modigliani, Kathy TITLE Child Care as an Occupation in a Culture of Indifference. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 189p. PUB TYPE Books (ON) Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Caregiver Role; *Child Caregivers; *Child Care Occupations; *Day Care; Early Childhood Education; Employment Practices; Family Day Care; Fringe Benefits; *Job Satisfaction; Professional Recognition; *Social Attitudes; Wages; Work Attitudes; *Work Environment; Work Experience IDENTIFIERS *Caregiver Attitudes; Cultural Values; Work Commitment ABSTRACT The study presented in this book explores the causes of the problems in child care as an occupation and points to important social and political solutions. Chapter 1 describes work conditions, benefits, and problems related to child care workers. Chapter 2 gives specific information on the nature of the study, its goals, and the methods used. Chapters 3 and 4 analyze the study's interviews of 28 child care workers interviewed during the fall of 1987 and spring of 1988, exploring their feelings about their week and what they expect of their working life in the future. Chapter 4 concludes that the problems with child care as an occupation are largely financial in origin, and chapter 5 presents an analysis of the economics of traditional women's work. This in turn points to consumerism of our culture, which lures the richest nation in the world into treating its children with indifference, as discussed in chapter 6. Chapter 7 analyzes parental and governmental spending on child care, revealing the conflicted relationships between mothers and caregivers analyzed in chapter 8. -

Our Children: Questions and Answers for Families of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Gender-Expansive and Queer Youth and Adults Is Copyrighted

OUR CHILDREN: QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS FOR FAMILIES OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANSGENDER, GENDER-EXPANSIVE AND QUEER YOUTH AND ADULTS If you or a loved one needs immediate assistance, please turn to the inside back cover for a list of crisis helplines, contact us at [email protected], visit our website at pflag.org, or call (202) 467-8180 to find the PFLAG chapter nearest you. ABOUT PFLAG Founded in 1972 with the simple act of a mother publicly supporting her gay son, PFLAG is the extended family of the LGBTQ community. Made up of families and allies united with people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ), PFLAG is committed to advancing equality through its mission of support, education, and advocacy. PFLAG has more than 400 chapters and 200,000 members and supporters crossing multiple generations of American families in major urban centers, small cities, and rural areas in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. This vast grassroots network is cultivated, resourced, and supported by the PFLAG National office (located in Washington, DC), the National Board of Directors, the Regional Directors Council, and our many advisory councils and boards. PFLAG is a nonprofit organization not affiliated with any political or religious institution. Our Vision. PFLAG envisions a world where diversity is celebrated and all people are respected, valued, and affirmed inclusive of their sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. Our Mission. By meeting people where they are and collaborating with -

CIEN - Cienega High School Feb 4, 2020 at 12:06 Pm 1Page Title List - 1 Line (160) by Title Call Number Alexandria 6.22.8 Selected:All Titles

CIEN - Cienega High School Feb 4, 2020 at 12:06 pm 1Page Title List - 1 Line (160) by Title Call Number Alexandria 6.22.8 Selected:All Titles Call # Title Author Copies Avail. American law yearbook 2011 1 1 Encyclopedia of education 1 1 Encyclopedia of religion 1 1 History behind the headlines : the origins of c... 1 1 Schirmer encyclopedia of film 1 1 Scholarships, fellowships, and loans : a guide... 1 1 UXL encyclopedia of drugs & addictive substa... 1 1 It's Not About the Bike Armstrong, Lance 3 3 It's Not About the Bike Armstrong, Lance 1 1 Time to let go McDaniel, Lurlene 2 2 001.4 FEL The Nobel prize : a history of genius, controve... Feldman, Burton. 2 2 001.4 MAC Information management Mackall, Joe. 2 2 001.9 BLA Extraordinary events and oddball occurrences Blackwood, Gary L. 2 2 001.9 FIT Cosmic test tube : extraterrestrial contact, the... Fitzgerald, Randall. 2 2 001.9 PED True fright : buried alive! and other true storie... Pedersen, Ted. 2 2 001.9 RAN The UFOs that never were Randles, Jenny. 2 2 001.94 AAS The Bermuda Triangle Aaseng, Nathan. 2 2 001.94 CAS Atlantis destroyed Castleden, Rodney. 2 2 001.94 CLA Unexplained! : strange sightings, incredible oc... Clark, Jerome. 2 2 001.94 INN The Bermuda Triangle Innes, Brian. 2 2 001.94 INN The cosmic joker Innes, Brian. 2 2 001.94 INN Where was Atlantis? Innes, Brian. 2 2 001.94 WIL The mammoth encyclopedia of the unsolved Wilson, Colin, 2 2 001.942 BIR Unsolved UFO mysteries : the world's most co.. -

Healing Through Ancestral Knowledge and Letters to Our Children: Mothering Infants During a Global Pandemic

genealogy Article Healing through Ancestral Knowledge and Letters to Our Children: Mothering Infants during a Global Pandemic Miriam G. Valdovinos 1,* , Noralis Rodríguez-Coss 2 and Rupal Parekh 3 1 Graduate School of Social Work, University of Denver, Denver, CO 80208, USA 2 Women’s and Gender Studies, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA 99258, USA; [email protected] 3 School of Social Work, University of Connecticut, Hartford, CT 06103, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 September 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020; Published: 21 December 2020 Abstract: The struggle for work–life balance amongst women in academia who are both mothers and scholars continues to be apparent during a global pandemic highlighting the systemic fissures and social inequalities ingrained in our society, including systems of higher learning. Women of color professors on the tenure track are vulnerable to the intersecting ways capitalism, sexism, and racism exacerbate the challenges faced by motherscholars, making it imperative to explore these nuances. While motherscholars may share advice about navigating family leave policies or strategizing scholarship goals, no one could have prepared us for our motherscholar roles during a pandemic. We were, in some ways, unprepared for giving birth with a heightened level of social isolation and feelings of loneliness, while racial unrest and loud exigencies to protect the lives of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) persist. Through three testimonios, we explore how ancestral/indigenous knowledge provides us with ways to persist, transform, and heal during these moments. We share letters written to each of our babies to encapsulate our praxis with ancestral knowledge on mothering.