How to Study Chess on Your Own

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZUGZWANGS in CHESS STUDIES G.Mcc. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. Van Der

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290629887 Zugzwangs in Chess Studies Article in ICGA journal · June 2011 DOI: 10.3233/ICG-2011-34205 CITATION READS 1 2,142 3 authors: Guy McCrossan Haworth Harold M.J.F. Van der Heijden University of Reading Gezondheidsdienst voor Dieren 119 PUBLICATIONS 354 CITATIONS 49 PUBLICATIONS 1,232 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eiko Bleicher 7 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Chess Endgame Analysis View project The Skilloscopy project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guy McCrossan Haworth on 23 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 82 ICGA Journal June 2011 NOTES ZUGZWANGS IN CHESS STUDIES G.McC. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. van der Heijden and E. Bleicher Reading, U.K., Deventer, the Netherlands and Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Van der Heijden’s ENDGAME STUDY DATABASE IV, HHDBIV, is the definitive collection of 76,132 chess studies. The zugzwang position or zug, one in which the side to move would prefer not to, is a frequent theme in the literature of chess studies. In this third data-mining of HHDBIV, we report on the occurrence of sub-7-man zugs there as discovered by the use of CQL and Nalimov endgame tables (EGTs). We also mine those Zugzwang Studies in which a zug more significantly appears in both its White-to-move (wtm) and Black-to-move (btm) forms. We provide some illustrative and extreme examples of zugzwangs in studies. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

CHESS FEDERATION Newburgh, N.Y

Announcing an important new series of books on CONTEMPORARY CHESS OPENINGS Published by Chess Digest, Inc.-General Editor, R. G. Wade The first book in this current series is a fresh look at 's I IAN by Leonard Borden, William Hartston, and Raymond Keene Two of the most brilliant young ployers pool their talents with one of the world's well-established authorities on openings to produce a modern, definitive study of the King's Indian Defence. An essen tial work of reference which will help master and amateur alike to win more games. The King's Indian Defence has established itself as one of the most lively and populor openings and this book provides 0 systematic description of its strategy, tactics, and variations. Written to provide instruction and under standing, it contains well-chosen illustrative games from octuol ploy, many of them shown to the very lost move, and each with an analysis of its salient features. An excellent cloth-bound book in English Descriptive Notation, with cleor type, good diagrams, and an easy-to-follow format. The highest quality at a very reasonable price. Postpaid, only $4.40 DON'T WAIT-ORDER NOW-THE BOOK YOU MUST HAVE! FLA NINGS by Raymond Keene Raymond Keene, brightest star in the rising galaxy of young British players, was undefeated in the 1968 British Championship and in the 1968 Olympiad at Lugano. In this book, he posses along to you the benefit of his studies of the King's Indian Attack and the Reti, Catalan, English, and Benko Larsen openings. The notation is Algebraic, the notes comprehensive but easily understood and right to the point. -

Chess Endgame News

Chess Endgame News Article Published Version Haworth, G. (2014) Chess Endgame News. ICGA Journal, 37 (3). pp. 166-168. ISSN 1389-6911 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/38987/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 166 ICGA Journal September 2014 CHESS ENDGAME NEWS G.McC. Haworth1 Reading, UK This note investigates the recently revived proposal that the stalemated side should lose, and comments further on the information provided by the FRITZ14 interface to Ronald de Man’s DTZ50 endgame tables (EGTs). Tables 1 and 2 list relevant positions: data files (Haworth, 2014b) provide chess-line sources and annotation. Pos.w-b Endgame FEN Notes g1 3-2 KBPKP 8/5KBk/8/8/p7/P7/8/8 b - - 34 124 Korchnoi - Karpov, WCC.5 (1978) g2 3-3 KPPKPP 8/6p1/5p2/5P1K/4k2P/8/8/8 b - - 2 65 Anand - Kramnik, WCC.5 (2007) 65. … Kxf5 g3 3-2 KRKRB 5r2/8/8/8/8/3kb3/3R4/3K4 b - - 94 109 Carlsen - van Wely, Corus (2007) 109. … Bxd2 == g4 7-7 KQR..KQR.. 2Q5/5Rpk/8/1p2p2p/1P2Pn1P/5Pq1/4r3/7K w Evans - Reshevsky, USC (1963), 49. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Hhdbiv.Nl for Ordering Details

see website www.hhdbiv.nl for ordering details. The world's largest endgame study database - edition 4 (HHdbIV) Introduction The fourth edition of the famous Harold van der Heijden endgame study database (HHdbIV) is available now. The new edition not only has more than eight thousand extra studies, but also the solutions of tens of thousands of studies have been corrected or updated. It is by far the most comprehensive collection of endgame studies available. Chess players can benefit from endgame studies by trying to solve them. This trains both one's calculation ability and tactical performance in the endgame. For the endgame study enthusiast, either admirer, cook hunter, composer or tourney judge HHdbIV is indispensable. Apart from the new studies the new version has many improvements over the previous edition. www.hhdbiv.nl What is an endgame study? An endgame study is a chess position presented as a puzzle with the stipulation White wins, or White draws, and has a unique solution. Although it looks like a game fragment, an endgame study has been composed. A good endgame study should have an entertaining solution with surprising moves or beautiful combinations that baffle chess players. It is also fun to try and solve endgame studies for both beginners and world class grandmasters as difficulty ranges from simple to very difficult. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endgame_study Chess Players "Studies are a very important part of the chess culture. I use a lot of studies for the training of imagination and calculations. The study database of Harold van der Heijden is the best source if you are looking for the less known positions". -

The World's Largest Endgame Study Database - Edition 5 (Hhdbv)

see website www.hhdbv.nl for ordering details. The world's largest endgame study database - edition 5 (HHdbV) Introduction The fifth edition of the famous Harold van der Heijden endgame study database (HHdbV) is available now. The new edition, with 85,619 studies not only has more than 9,000 new studies in comparison with HHdbIV, but also the solutions of tens of thousands of studies have been corrected or updated. It is by far the most comprehensive collection of endgame studies available. Chess players can benefit from endgame studies by trying to solve them. This trains both one's calculation ability and tactical performance in the endgame. For the endgame study enthusiast, either admirer, cook hunter, composer or tourney judge HHdbV is indispensable. Apart from the new studies the new version has many improvements over the previous editions. www.hhdbv.nl What is an endgame study? An endgame study is a chess position presented as a puzzle with the stipulation White wins, or White draws, and has a unique solution. Although it looks like a game fragment, an endgame study has been composed. A good endgame study should have an entertaining solution with surprising moves or beautiful combinations that baffle chess players. It is also fun to try and solve endgame studies for both beginners and world class grandmasters as difficulty ranges from simple to very difficult. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endgame_study Software The database is in PGN-format. This is a standard chess database format and can be accessed by commercial chess database programs (like ChessBase, Chess Assistant), commercial chess playing software (Fritz, Rybka, Shredder, etc.) and many freeware programs (e.g. -

THE PSYCHOLOGY of CHESS: an Interview with Author Fernand Gobet

FM MIKE KLEIN, the Chess Journalists Chess Life of America's (CJA) 2017 Chess Journalist of the Year, stepped OCTOBER to the other side of the camera for this month's cover shoot. COLUMNS For a list of all CJA CHESS TO ENJOY / ENTERTAINMENT 12 award winners, It Takes A Second please visit By GM Andy Soltis chessjournalism.org. 14 BACK TO BASICS / READER ANNOTATIONS The Spirits of Nimzo and Saemisch By GM Lev Alburt 16 IN THE ARENA / PLAYER OF THE MONTH Slugfest at the U.S. Juniors By GM Robert Hess 18 LOOKS AT BOOKS / SHOULD I BUY IT? Training Games By John Hartmann 46 SOLITAIRE CHESS / INSTRUCTION Go Bogo! By Bruce Pandolfini 48 THE PRACTICAL ENDGAME / INSTRUCTION How to Write an Endgame Thriller By GM Daniel Naroditsky DEPARTMENTS 5 OCTOBER PREVIEW / THIS MONTH IN CHESS LIFE AND US CHESS NEWS 20 GRAND PRIX EVENT / WORLD OPEN 6 COUNTERPLAY / READERS RESPOND Luck and Skill at the World Open BY JAMAAL ABDUL-ALIM 7 US CHESS AFFAIRS / GM Illia Nyzhnyk wins clear first at the 2018 World Open after a NEWS FOR OUR MEMBERS lucky break in the penultimate round. 8 FIRST MOVES / CHESS NEWS FROM AROUND THE U.S. 28 COVER STORY / ATTACKING CHESS 9 FACES ACROSS THE BOARD / How Practical Attacking Chess is Really Conducted BY AL LAWRENCE BY IM ERIK KISLIK 51 TOURNAMENT LIFE / OCTOBER The “secret sauce” to good attacking play isn’t what you think it is. 71 CLASSIFIEDS / OCTOBER CHESS PSYCHOLOGY / GOBET SOLUTIONS / OCTOBER 32 71 The Psychology of Chess: An Interview with Author 72 MY BEST MOVE / PERSONALITIES Fernand Gobet THIS MONTH: FM NATHAN RESIKA BY DR. -

April 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 48, Number 2 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION April 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT COLORADO SCHOLASTIC ONLINE CHAMPIONSHIP Volume 48, Number 2 Colorado Chess Informant April 2021 From the Editor With measured steps, the Colorado chess scene may just be com- ing back to life. It has been announced that the Colorado Open has been sched- uled for Labor Day weekend this year - albeit with safety proto- cols in place. Be sure to check out the website as the date nears (www.ColoradoChess.com) because as we are aware, things The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a could change. The Denver Chess Club has also announced a Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- tournament in June of this year - go to their website tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are (www.DenverChess.com) for more information on that one. tax deductible. It is with a heavy heart and profound sadness that a friend and Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) ‘chess bud’ of mine has passed away. Not long after his 70th memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to birthday in January, Michael Wokurka collapsed at his home on additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- the 22nd - and never regained consciousness. No prior warning tic tournament membership is available for $3. or health issues were known. His obituary online is listed here: ● Send address changes to - Attn: Alexander Freeman to the https://tinyurl.com/2rz9zrca. He loved the game of chess, and email address [email protected]. -

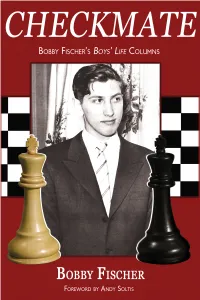

Checkmate Bobby Fischer's Boys' Life Columns

Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns Checkmate Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns by Bobby Fischer Foreword by Andy Soltis 2016 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Checkmate Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns by Bobby Fischer ISBN: 978-1-941270-51-6 (print) ISBN: 978-1-941270-52-3 (eBook) © Copyright 2016 Russell Enterprises, Inc. & Hanon W. Russell All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Chess columns written by Bobby Fischer appeared from December 1966 through January 1970 in the magazine Boys’ Life, published by the Boy Scouts of America. Russell Enterprises, Inc. thanks the Boy Scouts of America for its permission to reprint these columns in this compilation. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Editing and proofreading by Peter Kurzdorfer Cover by Janel Lowrance 2 Table of Contents Foreword 4 April 53 by Andy Soltis May 59 From the Publisher 6 Timeline 60 June 61 July 69 Timeline 7 Timeline 70 August 71 1966 September 77 December 9 October 78 November 84 1967 February 11 1969 March 17 February 85 April 19 March 90 Timeline 22 May 23 April 91 June 24 July 31 May 98 Timeline 32 June 99 August 33 July 107 September 37 August 108 Timeline 38 September 115 October 39 October 116 November 46 November 122 December 123 1968 February 47 1970 March 52 January 128 3 Checkmate Foreword Bobby Fischer’s victory over Emil Nikolic at Vinkovci 1968 is one of his most spectacular, perhaps the last great game he played in which he was the bold, go-for-mate sacrificer of his earlier years. -

A GUIDE to SCHOLASTIC CHESS (11Th Edition Revised June 26, 2021)

A GUIDE TO SCHOLASTIC CHESS (11th Edition Revised June 26, 2021) PREFACE Dear Administrator, Teacher, or Coach This guide was created to help teachers and scholastic chess organizers who wish to begin, improve, or strengthen their school chess program. It covers how to organize a school chess club, run tournaments, keep interest high, and generate administrative, school district, parental and public support. I would like to thank the United States Chess Federation Club Development Committee, especially former Chairman Randy Siebert, for allowing us to use the framework of The Guide to a Successful Chess Club (1985) as a basis for this book. In addition, I want to thank FIDE Master Tom Brownscombe (NV), National Tournament Director, and the United States Chess Federation (US Chess) for their continuing help in the preparation of this publication. Scholastic chess, under the guidance of US Chess, has greatly expanded and made it possible for the wide distribution of this Guide. I look forward to working with them on many projects in the future. The following scholastic organizers reviewed various editions of this work and made many suggestions, which have been included. Thanks go to Jay Blem (CA), Leo Cotter (CA), Stephan Dann (MA), Bob Fischer (IN), Doug Meux (NM), Andy Nowak (NM), Andrew Smith (CA), Brian Bugbee (NY), WIM Beatriz Marinello (NY), WIM Alexey Root (TX), Ernest Schlich (VA), Tim Just (IL), Karis Bellisario and many others too numerous to mention. Finally, a special thanks to my wife, Susan, who has been patient and understanding. Dewain R. Barber Technical Editor: Tim Just (Author of My Opponent is Eating a Doughnut and Just Law; Editor 5th, 6th and 7th editions of the Official Rules of Chess). -

One of the First Things That Strikes the Endgame Study Enthusiast Is the Fact That There Have Been No Great British Composers

EG OCTOBER, 1965 One of the first things that strikes the endgame study enthusiast is the fact that there have been no great British composers. Certainly the British study has had its inspired moments, such as the famous study by Joseph which our first Tourney commemorates, but never has there been a plethora of fine composers, or even one who has really stood out from the rest. On the other hand, British problems have always been amongst the best, which to my mind indicates that chess composition is in our blood; furthermore, there is evidence that there is no lack of future problem talent at the present time. The reason for this lies, I am sure, in the lack of encouragement for composers and general interest among the chess public. It is to be hoped that the Chess Endgame Study Circle and its organ EG will provide the necessary stimulus for the budding composer by (a) keeping him in touch with recent developments (b) providing material for the improvement of his techniques (c) giving him the chance to display his best work prominently and (d) by holding regular meetings to stimulate discussion and allow for lectures by leading composers. More generally, the mere existence of E G should increase interest among chessplayers; by holding tourneys, by acting as a source book, by encouraging discussion, it should cause chess columnists and others to devote more time and space to studies. There is a place for the purely aesthetic in the average chess player's world, provided that it is intelligently presented.