A Case Study of the Torres Strait Regional Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACA Qld 2019 National Conference

➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ • • • • • • • • • • • • • Equal Remuneration Order (and Work Value Case) • 4 yearly review of Modern Awards • Family friendly working conditions (ACA Qld significant involvement) • Casual clauses added to Modern Awards • Minimum wage increase – 3.5% • Employment walk offs, strikes • ACA is pursuing two substantive claims, • To provide employers with greater flexibility to change rosters other than with 7 days notice. • To allow ordinary hours to be worked before 6.00am or after 6.30pm. • • • • • Electorate Sitting Member Opposition Capricornia Michelle Landry [email protected] Russell Robertson Russell.Robertson@quee nslandlabor.org Forde Bert Van Manen [email protected] Des Hardman Des.Hardman@queenslan dlabor.org Petrie Luke Howarth [email protected] Corinne Mulholland Corinne.Mulholland@que enslandlabor.org Dickson Peter Dutton [email protected] Ali France Ali.France@queenslandla bor.org Dawson George Christensen [email protected] Belinda Hassan Belinda.Hassan@queensl .au andlabor.org Bonner Ross Vasta [email protected] Jo Briskey Jo.Briskey@queenslandla bor.org Leichhardt Warren Entsch [email protected] Elida Faith Elida.Faith@queenslandla bor.org Brisbane Trevor Evans [email protected] Paul Newbury paul.newbury@queenslan dlabor.org Bowman Andrew Laming [email protected] Tom Baster tom.Baster@queenslandla bor.org Wide Bay Llew O’Brien [email protected] Ryan Jane Prentice [email protected] Peter Cossar peter.cossar@queensland -

Here Our Heart Jiggled with Joy: Celebrating One Year Since Historic Nuclear Dump Decision 38 Material Has Been Reprinted from Another Source

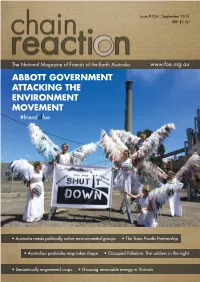

Issue #124 | September 2015 RRP $5.50 The National Magazine of Friends of the Earth Australia www.foe.org.au ABBOTT GOVERNMENT ATTACKING THE ENVIRONMENT MOVEMENT #friendoffoe • Australia needs politically active environmental groups • The Trans Pacific Partnership • Australian pesticides map takes shape • Occupied Palestine: The soldiers in the night • Semantically engineered crops • Growing renewable energy in Victoria Edition #124 − September 2015 REGULAR ITEMS Publisher - Friends of the Earth, Australia Chain Reaction ABN 81600610421 Join Friends of the Earth 4 FoE Australia ABN 18110769501 FoE Australia News 5 www.foe.org.au FoE Australia Contacts inside back cover youtube.com/user/FriendsOfTheEarthAUS CONTENTS twitter.com/FoEAustralia facebook.com/pages/Friends-of-the-Earth- Australia/16744315982 flickr.com/photos/foeaustralia GOVERNMENT ATTACKS ON ENVIRONMENTAL GROUPS Threats against environment groups, threats against democracy 10 Chain Reaction website – Ben Courtice www.foe.org.au/chain-reaction Australia needs politically active environmental groups – Susan Laurance and Bill Laurance 11 Silence on the agenda for enviro-charity inquiry – Andrew Leigh 13 Chain Reaction contact details PO Box 222,Fitzroy, Victoria, 3065. email: [email protected] phone: (03) 9419 8700 ARTICLES Chain Reaction team Australian pesticides map takes shape – Anthony Amis 15 Jim Green, Tessa Sellar, Franklin Bruinstroop, Some reflections on Friends of the Earth: 1974−76– Neil Barrett 16 Michaela Stubbs, Claire Nettle River Country Campaign – Morgana -

List of Senators

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 19.1 – 20 September 2021 No. Name Electorate & Party Electorate office details & email address Parliament House State/Territory telephone & fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7860 Minister for Home Affairs QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4023 VIC 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road, Fax: (02) 6277 4074 Doncaster VIC 3108 (PO Box 124, Doncaster VIC 3108) Tel: (03) 9848 9900, Fax: (03) 9848 2741 7. -

Marginal Seat Analysis – 2019 Federal Election

Australian Landscape Architects Vote 2019 Marginal Seat Analysis – 2019 Federal Election Prepared by Daniel Bennett, Fellow, AILA The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) classifies seats based on the percentage margin won on a ‘two candidate preferred’ basis, which creates a calculation for the swing to change hands. Further, the AEC classify seats based on the following terms: • Marginal (less than 6% swing or 56% of the vote) • Fairly safe (between 6-10% swing or 56-60% of the vote) • Safe (more than 10% swing required and more than 60% of the vote) As an ardent follower of all elections, I offer the following analysis to assist AILA in preparing pre- election materials and perhaps where to focus efforts. As the current Government is a Coalition of the Liberal and National Party, my focus is on the fairly reliable (yet not completely correct) assumption that they have the most to lose and will find it hard to retain the treasury benches. Polls consistently show the Coalition on track to lose from 8 up to 24 seats, which is in plain terms a landslide to the ALP. However polls are just that and have been wrong so many times. So lets focus on what we know. The Marginals. According to the latest analysis by the AEC and the ABC’s Antony Green, the Coalition has 22 marginal seats, there are now 8 cross bench seats, of which 3 are marginal and the ALP have 24 marginal seats. This is a total of 49 marginal seats – a third of all seats! With a new parliament of 151 seats, a new government requires 76 seats to win a majority. -

Email Addresses – Qld

Email Addresses for Queensland MPs as at 18 Sept 2019 ALP Ms Terri Butler MP [email protected] Dr Jim Chalmers MP [email protected] Mr Milton Dick MP [email protected] Hon Shayne Neumann MP [email protected] Mr Graham Perrett MP [email protected] Ms Anika Wells MP [email protected] LIBERAL NATIONAL Hon Karen Andrews MP [email protected] Ms Angie Bell MP [email protected] Hon Scott Buchholz MP [email protected] Mr George Christensen MP [email protected] Hon Peter Dutton MP [email protected] Hon Warren Entsch MP [email protected] Hon Trevor Evans MP [email protected] Hon Luke Howarth MP [email protected] Mr Andrew Laming MP [email protected] Hon Michelle Landry MP [email protected] Hon David Littleproud MP [email protected] Hon Dr John McVeigh MP [email protected] Mr Ted O'Brien MP [email protected] Mr Llew O'Brien MP [email protected] Mr Ken O'Dowd MP [email protected] Hon Keith Pitt MP [email protected] Hon Stuart Robert MP [email protected] Mr Julian Simmonds MP [email protected] Mr Phillip Thompson OAM, MP [email protected] Mr Bert van Manen MP [email protected] Mr Ross Vasta MP [email protected] Mr Andrew Wallace MP [email protected] Mr Terry Young MP [email protected] INDEPENDENT Hon Bob Katter MP [email protected] And to save you even more time, here they are ready to paste into “TO” and send your message. -

Cairns Regional Council (Council) Pre-Submission

ENQUIRIES: Nick Masasso PHONE: 07 4044 3522 OUR REF: #6575380 27 January 2021 The Hon Josh Frydenberg Treasurer Dear Treasurer 2021-22 Federal Budget Cairns Regional Council (Council) Pre-Submission Table 1: Recommendations In formulating the 2021-22 Budget, Treasury should: 1. Consider the recommended actions contained in the COVID-19 Cairns Local Recovery Plan and develop and implement initiatives that will support the Plan’s implementation. 2. Establish a dedicated funding stream to support investment in urban water supply infrastructure projects such as the Cairns Water Security – Stage 1 project. This initiative is consistent with the Town and City Water Security High Priority Infrastructure Initiative identified by Infrastructure Australia. Provision for this funding stream should be made within the 2021-22 Budget and across the forward estimates. 3. Establish a dedicated funding stream to support investment in new iconic tourism infrastructure and experiences such as the Cairns Gallery Precinct project to support the medium to long term economic recovery of tourism destinations whose economies have been severely impacted by COVID-19. Provision for this funding stream should be made within the 2021-22 Budget and across the forward estimates and be in addition to the recently announced Building Better Regions Fund Round 5. 4. Implement the recommendations made in the JobKeeper Payment Scheme – Cairns Submission made on 17 December 2020. Specifically: a. That the expiry date for the JobKeeper Payment Scheme be extended from 28 March 2021 to 30 June 2021 with the fortnightly payment for this period retained at 100% of the level applied from 4 January to 28 March 2021 (i.e. -

List of Members 46Th Parliament Volume 6.4 – 03 June 2020

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 6.4 – 03 June 2020 No. Name Electorate, Party Electorate office details, E-mail address Parliament House State/Territory telephone, fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422, Fax: N/A 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517, Fax: (08) 9409 9361 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7070 Minister for Industry, Science and QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Technology Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. -

Consensus Report of the Parliamentary Energy Committee

House of Representatives Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy Inquiry into modernising Australia’s electricity grid Issue date: 5 February 2018 Consensus report of the parliamentary energy committee The House of Representatives Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy today released the report of its inquiry into modernising Australia’s electricity grid, which is a consensus, cross-party report on a highly contested policy area. Like many countries around the world, the electricity system in Australia is in a period of rapid transition, driven by changes in the generation mix, new technologies, the development of government policies aimed at reducing emissions, and changes in how consumers interact with the system. This period of transition presents both challenges and opportunities, from improving the security, reliability, and affordability of the electricity supply, to contributing to Australia’s emission reduction commitments. The Committee consisted of: Andrew Broad MP (The Nationals, Member for Mallee) Pat Conroy MP (ALP, Member for Shortlandand, Shadow Assistant Minister for Climate Change and Energy) the Hon. Warren Entsch MP (Liberal Party of Australia, Member for Leichhardt) Trevor Evans MP (Liberal Party of Australia, Member for Brisbane) Luke Howarth MP (Liberal Party of Australia, Member for Petrie) Craig Kelly MP (Liberal Party of Australia, Member for Hughes and Chair of the backbench environment and energy committee) Peter Khalil MP (ALP, Member for Wills) Anne Stanley MP (ALP, Member for Werriwa) Adam Bandt MP (Australian Greens, Member for Melbourne). The Committee Chair, Andrew Broad MP (The Nationals, Member for Mallee), said that “modernising the electricity grid is a big project for a big country. -

Press Release the Hon

PRESS RELEASE THE HON. TONY ABBOTT MP, LEADER OF THE FEDERAL COALITION A TEAM TO BUILD A STRONGER AUSTRALIA The incoming Coalition Government will restore strong, stable and accountable government to build a more prosperous Australia. This is the team that will scrap the carbon tax, end the waste, stop the boats, build the roads of the twenty first century and deliver the strong and dynamic economy that we need. First term governments are best served by Cabinets with extensive ministerial experience. Fifteen members of the incoming Cabinet have previous ministerial experience. The four members of Cabinet without ministerial experience have made significant contributions to the Shadow Ministry. The simplification of ministerial and departmental titles reflects my determination to run a “back to basics” government. The Australian people expect a government that is upfront, speaks plainly and does the essentials well. The Cabinet will be assisted by a strong team of ministers with proven capacity to implement the Government’s policies. Parliamentary secretaries will assist senior ministers and be under their direction. Good government requires a strong Coalition. As Deputy Prime Minister and as Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development, the Hon Warren Truss MP will be responsible for ensuring the Government delivers on its major infrastructure commitments across Australia. Mr Jamie Briggs MP will be the Assistant Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development with specific responsibility for roads and delivery of our election commitments across metropolitan and regional Australia. The Hon Julie Bishop MP will serve as Minister for Foreign Affairs and will be a strong voice for Australia during a time when Australia is a member of the United Nations Security Council. -

Annual Report 2015-2016

TORRES SHIRE COUNCIL TORRES SHIRE COUNCIL - SHIRE COUNCIL TORRES Annual Report 2015 to 2016 2015 to Annual Report ANNUAL REPORT | 2015 to 2016 To lead, provide & facilitate Disclaimer: Torres Shire Council advises that this publication may contain images of information of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. TORRES SHIRE COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2015 - 2016 INDEX 04. Introduction 05. The Torres Strait 06. History 08. Torres Shire in Brief 09. Torres Shire 11. Strategic Direction 12. Partnerships 13. Contacting the Council 14. Report from the Mayor 16. Message from the CEO 18. Our Councillors 21. Advisory Committees 22. Councillors’ Remuneration 24. Council Meetings & Attendances 25. Executive Management Team 26. Organisation Chart 27. Corporate Governance 30. Statistics & Other Information 31. Community Snapshots APPENDICES 43. Appendix 1 - Financial Statements 86. Appendix 2 - Independent Auditor’s Report 88. Appendix 3 - Current Year Financial Sustainability Report 90. Appendix 4 - Current Year Financial Audit Report 92. Appendix 5 - Long Term Financial Sustainability Statement INTRODUCTION This Torres Shire Council Annual Report provides after the end of the financial year to which the an account of the organisation’s performance, report relates. activities and other information for the financial year from 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016 The Annual Report shows transparency in COPIES accountability for all financial and operational Objectives and strategies addressed in this performances throughout the year and contains Annual Report are contained in the Torres Shire important information for Residents and Council 2014 -2018 Corporate Plan. Ratepayers, Councillors and Staff, community groups, government, developers / investors Copies of both the Corporate Plan and this and other interested parties, on operations, Annual Report are available from: achievements, challenges, culture, purposes and plans for the future. -

The Australian Capital Territory New South Wales

Names and electoral office addresses of Federal Members of Parliament The Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................................................... 1 New South Wales ............................................................................................................................... 1 Northern Territory .............................................................................................................................. 4 Queensland ........................................................................................................................................ 4 South Australia .................................................................................................................................. 6 Tasmania ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Victoria ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Western Australia .............................................................................................................................. 9 How to address Members of Parliament ........................................................................... 10 The Australian Capital Territory Ms Gai Brodtmann, MP Hon Dr Andrew Leigh, MP 205 Anketell St, Unit 8/1 Torrens St, Tuggeranong ACT, 2900 Braddon ACT, 2612 New South Wales Hon Anthony Abbott, -

Michael Wilson Thesis

THE POLITICS OF PRIVACY PROTECTION: AN ANALYSIS OF RESISTANCE TO METADATA RETENTION AND ENCRYPTION ACCESS LAWS Michael Peter Wilson Bachelor of Justice (Honours) Bachelor of Behavioural Science A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Justice, Faculty of Law Queensland University of Technology 2020 Abstract The politics of privacy protection are contested. In recent years, the Australian Government has justified the expansion of surveillance powers, under the Data Retention Act (2015) and Encryption Access Act (2018), by invoking the ‘problem of going dark’ – a claim that the investigative capabilities of law enforcement agencies are being undermined by the use of privacy-enhancing technologies. As such, the ‘problem of going dark’ draws a moral equivalence between privacy protection and methods of evading criminal investigations. This thesis examines the politics of privacy protection within the context of Australia’s national debates about digital surveillance powers, focusing on how privacy advocates contest this moral equivalence embedded within the ‘problem of going dark’. Specifically, this research involves a political discourse analysis (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985) of twenty-one (n=21) semi-structured interviews with Australian privacy advocates involved in campaigns opposing data retention and encryption access laws. Using the analytical constructs of signification, subjectivation, and identification, the research examines how privacy advocates challenge the ‘problem of going dark’, discursively position the subjects of surveillance laws, and mobilise through the construction of shared identities. This thesis argues that Australian privacy advocates contest the moral equivalence embedded within the ‘problem of going dark’ via the articulation of a civic duty to disrupt the relations of domination that enable ‘morally arbitrary’ surveillance under the Data Retention Act (2015) and Encryption Access Act (2018).