Michael Wilson Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Political Writings 2009-10

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament BIBLIOGRAPHY www.aph.gov.au/library Selected Australian political writings 2009‐10 Contents Biographies ............................................................................................................................. 2 Elections, electorate boundaries and electoral systems ......................................................... 3 Federalism .............................................................................................................................. 6 Human rights ........................................................................................................................... 6 Liberalism and neoliberalism .................................................................................................. 6 Members of Parliament and their staff .................................................................................... 7 Parliamentary issues ............................................................................................................... 7 Party politics .......................................................................................................................... 13 Party politics- Australian Greens ........................................................................................... 14 Party politics- Australian Labor Party .................................................................................... 14 Party politics- -

ACA Qld 2019 National Conference

➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ • • • • • • • • • • • • • Equal Remuneration Order (and Work Value Case) • 4 yearly review of Modern Awards • Family friendly working conditions (ACA Qld significant involvement) • Casual clauses added to Modern Awards • Minimum wage increase – 3.5% • Employment walk offs, strikes • ACA is pursuing two substantive claims, • To provide employers with greater flexibility to change rosters other than with 7 days notice. • To allow ordinary hours to be worked before 6.00am or after 6.30pm. • • • • • Electorate Sitting Member Opposition Capricornia Michelle Landry [email protected] Russell Robertson Russell.Robertson@quee nslandlabor.org Forde Bert Van Manen [email protected] Des Hardman Des.Hardman@queenslan dlabor.org Petrie Luke Howarth [email protected] Corinne Mulholland Corinne.Mulholland@que enslandlabor.org Dickson Peter Dutton [email protected] Ali France Ali.France@queenslandla bor.org Dawson George Christensen [email protected] Belinda Hassan Belinda.Hassan@queensl .au andlabor.org Bonner Ross Vasta [email protected] Jo Briskey Jo.Briskey@queenslandla bor.org Leichhardt Warren Entsch [email protected] Elida Faith Elida.Faith@queenslandla bor.org Brisbane Trevor Evans [email protected] Paul Newbury paul.newbury@queenslan dlabor.org Bowman Andrew Laming [email protected] Tom Baster tom.Baster@queenslandla bor.org Wide Bay Llew O’Brien [email protected] Ryan Jane Prentice [email protected] Peter Cossar peter.cossar@queensland -

Australia 2019

Australia Free 77 100 A Obstacles to Access 23 25 B Limits on Content 29 35 C Violations of User Rights 25 40 Last Year's Score & Status 79 100 Free Overview Internet freedom in Australia declined during the coverage period. The country’s information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure is well developed, and prices for connections are low, ensuring that much of the population enjoys access to the internet. However, a number of website restrictions, such as those related to online piracy or “abhorrent” content, limit the content available to users. The March 2019 terrorist attack on mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, prompted internet service providers (ISPs) to block certain websites and the government subsequently introduced a new law that criminalized the failure to delete “abhorrent” content. Other legal changes—including court decisions expanding the country’s punitive defamation standards, an injunction silencing digital media coverage of a high-profile trial, and a problematic law that undermines encryption—shrunk the space for free online expression in Australia. Finally, an escalating series of cyberattacks sponsored by China profoundly challenged the security of Australia’s digital sphere. Australia is a democracy with a strong record of advancing and protecting political rights and civil liberties. Recent challenges to these freedoms have included the threat of foreign political influence, harsh policies toward asylum seekers, and ongoing disparities faced by indigenous Australians. Key Developments June 1, 2018 – May 31, 2019 After the March 2019 Christchurch attack, in which an Australian man who had espoused white supremacist views allegedly killed 51 people at two New Zealand mosques, ISPs acted independently to block access to more than 40 websites that hosted the attacker’s live-streamed video of his crimes. -

Privacy and Data Protection in Australia: a Critical Overview (Extended Abstract)

Privacy and Data Protection in Australia: a Critical overview (extended abstract) David Watts1, Pompeu Casanovas2,3 1 La Trobe Law School, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia 2 UAB Institute of Law and Technology, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain Abstract. This extended abstract describes the regulation of privacy under Aus- tralian laws and policies. In the CRC D2D programme, we will develop a strategy to model legal requirements in a situation that is far from clear. Law enforcement agencies are facing big floods of data to be acquired, stored, assessed and used. We will propose in the final paper a linked data regulatory model to organise and set the legal and policy requirements to model privacy in this unstructured con- text. Keywords: Australian privacy law, legal requirements, privacy modelling 1 Introduction Australia has a federal system of government that embodies a number of the structural elements of the US Constitutional system but retains a Constitutional monarchy. It con- sists of a national government (the Commonwealth), six state governments (New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia) as well as two Territories (the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory). Under this system, specific Constitutional powers are conferred on the Common- wealth. Any other powers not specifically conferred on the Commonwealth are retained by the States (and, to a lesser extent, the Territories). There is no general law right to privacy in Australia. Although Australia is a signa- tory to the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights, the international law right to privacy conferred under Article 17 of the ICCPR has not been enacted into Australia’s domestic law. -

Legitimacy in the New Regulatory State

LEGITIMACY IN THE NEW REGULATORY STATE KAREN LEE A THESIS IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF LAW MARCH 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... I PUBLICATIONS AND PRESENTATIONS ARISING FROM THE WRITING OF THE THESIS .. III GLOSSARY AND TABLE OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................. IV CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 I JUSTIFICATION FOR RESEARCH AND ITS APPROACH .......................................... 4 A THE NEED FOR EMPIRICAL STUDY OF INDUSTRY RULE-MAKING ....................... 4 B PART 6 RULE-MAKING ....................................................................................... 7 1 THE COMMUNICATIONS ALLIANCE ................................................................ 8 2 CONSUMER CODES ....................................................................................... 10 C PROCEDURAL AND INSTITUTIONAL LEGITIMACY, RESPONSIVENESS AND THEIR CRITERIA ......................................................................................................... 11 II TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................ 15 A CONSUMER AND PUBLIC INTERESTS................................................................. 15 1 CONSUMER INTEREST ................................................................................. -

Here Our Heart Jiggled with Joy: Celebrating One Year Since Historic Nuclear Dump Decision 38 Material Has Been Reprinted from Another Source

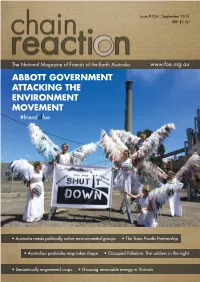

Issue #124 | September 2015 RRP $5.50 The National Magazine of Friends of the Earth Australia www.foe.org.au ABBOTT GOVERNMENT ATTACKING THE ENVIRONMENT MOVEMENT #friendoffoe • Australia needs politically active environmental groups • The Trans Pacific Partnership • Australian pesticides map takes shape • Occupied Palestine: The soldiers in the night • Semantically engineered crops • Growing renewable energy in Victoria Edition #124 − September 2015 REGULAR ITEMS Publisher - Friends of the Earth, Australia Chain Reaction ABN 81600610421 Join Friends of the Earth 4 FoE Australia ABN 18110769501 FoE Australia News 5 www.foe.org.au FoE Australia Contacts inside back cover youtube.com/user/FriendsOfTheEarthAUS CONTENTS twitter.com/FoEAustralia facebook.com/pages/Friends-of-the-Earth- Australia/16744315982 flickr.com/photos/foeaustralia GOVERNMENT ATTACKS ON ENVIRONMENTAL GROUPS Threats against environment groups, threats against democracy 10 Chain Reaction website – Ben Courtice www.foe.org.au/chain-reaction Australia needs politically active environmental groups – Susan Laurance and Bill Laurance 11 Silence on the agenda for enviro-charity inquiry – Andrew Leigh 13 Chain Reaction contact details PO Box 222,Fitzroy, Victoria, 3065. email: [email protected] phone: (03) 9419 8700 ARTICLES Chain Reaction team Australian pesticides map takes shape – Anthony Amis 15 Jim Green, Tessa Sellar, Franklin Bruinstroop, Some reflections on Friends of the Earth: 1974−76– Neil Barrett 16 Michaela Stubbs, Claire Nettle River Country Campaign – Morgana -

List of Senators

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 19.1 – 20 September 2021 No. Name Electorate & Party Electorate office details & email address Parliament House State/Territory telephone & fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7860 Minister for Home Affairs QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4023 VIC 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road, Fax: (02) 6277 4074 Doncaster VIC 3108 (PO Box 124, Doncaster VIC 3108) Tel: (03) 9848 9900, Fax: (03) 9848 2741 7. -

Mark Burdon Thesis

THE CONCEPTUAL AND OPERATIONAL COMPATIBILITY OF DATA BREACH NOTIFICATION AND INFORMATION PRIVACY LAWS Mark Burdon M.Sc. (Econ) Public Policy (Lon), LLB (Hons) (London South Bank University, UK) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD by publications Faculty of Law Queensland University of Technology 2011 Keywords Data Breach Notification Law – Information Privacy Law – Data Protection – Contextualisation - Information Security Law ii Abstract Mandatory data breach notification laws are a novel and potentially important legal instrument regarding organisational protection of personal information. These laws require organisations that have suffered a data breach involving personal information to notify those persons that may be affected, and potentially government authorities, about the breach. The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) has proposed the creation of a mandatory data breach notification scheme, implemented via amendments to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth). However, the conceptual differences between data breach notification law and information privacy law are such that it is questionable whether a data breach notification scheme can be solely implemented via an information privacy law. Accordingly, this thesis by publications investigated, through six journal articles, the extent to which data breach notification law was conceptually and operationally compatible with information privacy law. The assessment of compatibility began with the identification of key issues related to data breach notification law. The first article, Stakeholder Perspectives Regarding the Mandatory Notification of Australian Data Breaches started this stage of the research which concluded in the second article, The Mandatory Notification of Data Breaches: Issues Arising for Australian and EU Legal Developments (‘Mandatory Notification‘). A key issue that emerged was whether data breach notification was itself an information privacy issue. -

Review of Secrecy Laws

Review of Secrecy Laws ISSUES PAPER You are invited to provide a submission or comment on this Issues Paper ISSUES PAPER 34 December 2008 This Issues Paper reflects the law as at 1 November 2008. © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in whole or part, subject to acknowledgement of the source, for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), all other rights are reserved. Requests for further authorisation should be directed by letter to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch, Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or electronically via www.ag.gov.au/cca. ISBN-978-0-9804153-4-6 Commission Reference: IP 34 The Australian Law Reform Commission was established on 1 January 1975 by the Law Reform Commission Act 1973 (Cth) and reconstituted by the Australian Law Reform Commission Act 1996 (Cth). The office of the ALRC is at Level 25, 135 King Street, Sydney, NSW, 2000, Australia. All ALRC publications can be made available in a range of accessible formats for people with disabilities. If you require assistance, please contact the ALRC. Telephone: within Australia (02) 8238 6333 International +61 2 8238 6333 TTY: (02) 8238 6379 Facsimile: within Australia (02) 8238 6363 International +61 2 8238 6363 E-mail: [email protected] ALRC homepage: www.alrc.gov.au Printed by Ligare Making a submission Any public contribution to an inquiry is called a submission and these are actively sought by the ALRC from a broad cross-section of the community, as well as those with a special interest in the particular inquiry. -

Telecommunications Act 1997

Telecommunications Act 1997 Act No. 47 of 1997 as amended This compilation was prepared on 26 November 2008 taking into account amendments up to Act No. 117 of 2008 [Note: Subsections 531F(1) and (2) and paragraphs 531G(2)(e) and (3A)(e) cease to have effect on 27 May 2009, see subsections 531F(3), 531G(3) and (3B)] The text of any of those amendments not in force on that date is appended in the Notes section The operation of amendments that have been incorporated may be affected by application provisions that are set out in the Notes section Prepared by the Office of Legislative Drafting and Publishing, Attorney-General’s Department, Canberra Contents Part 1—Introduction 1 1 Short title [see Note 1].......................................................................1 2 Commencement [see Note 1].............................................................1 3 Objects...............................................................................................1 4 Regulatory policy ..............................................................................3 5 Simplified outline ..............................................................................3 6 Main index.........................................................................................7 7 Definitions.........................................................................................8 8 Crown to be bound ..........................................................................18 9 Extra-territorial application .............................................................18 -

Marginal Seat Analysis – 2019 Federal Election

Australian Landscape Architects Vote 2019 Marginal Seat Analysis – 2019 Federal Election Prepared by Daniel Bennett, Fellow, AILA The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) classifies seats based on the percentage margin won on a ‘two candidate preferred’ basis, which creates a calculation for the swing to change hands. Further, the AEC classify seats based on the following terms: • Marginal (less than 6% swing or 56% of the vote) • Fairly safe (between 6-10% swing or 56-60% of the vote) • Safe (more than 10% swing required and more than 60% of the vote) As an ardent follower of all elections, I offer the following analysis to assist AILA in preparing pre- election materials and perhaps where to focus efforts. As the current Government is a Coalition of the Liberal and National Party, my focus is on the fairly reliable (yet not completely correct) assumption that they have the most to lose and will find it hard to retain the treasury benches. Polls consistently show the Coalition on track to lose from 8 up to 24 seats, which is in plain terms a landslide to the ALP. However polls are just that and have been wrong so many times. So lets focus on what we know. The Marginals. According to the latest analysis by the AEC and the ABC’s Antony Green, the Coalition has 22 marginal seats, there are now 8 cross bench seats, of which 3 are marginal and the ALP have 24 marginal seats. This is a total of 49 marginal seats – a third of all seats! With a new parliament of 151 seats, a new government requires 76 seats to win a majority. -

Download PDF Read More

This Issues Paper reflects the law as at 30 November 2006 © Commonwealth of Australia 2006 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in whole or part, subject to acknowledgement of the source, for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), all other rights are reserved. Requests for further authorisation should be directed by letter to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch, Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or electronically via www.ag.gov.au/cca. ISBN 0-9758213-7-7 Commission Reference: IP 32 The Australian Law Reform Commission was established on 1 January 1975 by the Law Reform Commission Act 1973 (Cth) and reconstituted by the Australian Law Reform Commission Act 1996 (Cth). The office of the ALRC is at Level 25, 135 King Street, Sydney, NSW, 2000, Australia. All ALRC publications can be made available in a range of accessible formats for people with disabilities. If you require assistance, please contact the ALRC. Telephone: within Australia (02) 8238 6333 International +61 2 8238 6333 TTY: (02) 8238 6379 Facsimile: within Australia (02) 8238 6363 International +61 2 8238 6363 E-mail: [email protected] ALRC homepage: www.alrc.gov.au Printed by Canprint Communications Pty Ltd Making a submission Any public contribution to an inquiry is called a submission and these are actively sought by the ALRC from a broad cross-section of the community, as well as those with a special interest in the inquiry.