Comments to the CTB Rail Subcommittee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accelerating Implementation of ECP Brake Emulator Technology DTFR53-BAA-2013-1 DTFR53-13-C-00067L- Task 01 6

U.S. Department of Transportation Accelerating Implementation of ECP Brake Federal Railroad Emulator Technology Administration Office of Research, Development and Technology Washington, DC 20590 DOT/FRA/ORD-19/26 Final Report August 2019 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. The United States Government assumes no liability for the content or use of the material contained in this document. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. -

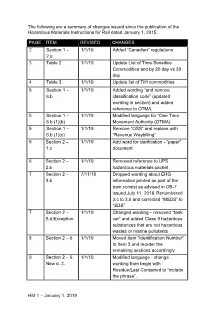

January 1, 2019 the Following Are a Summary of Changes Issued Since

The following are a summary of changes issued since the publication of the Hazardous Materials Instructions for Rail dated January 1, 2015. PAGE ITEM REVISED CHANGES 2 Section 1 – 1/1/19 Added “Canadian” regulations 2.a 3 Table 2 1/1/19 Update List of Time Sensitive Commodities and by 20 day vs 30 day 4 Table 3 1/1/19 Update list of TIH commodities 5 Section 1 – 1/1/19 Added wording “and remove 6.b classification code” (updated wording in section) and added reference to OTMA. 5 Section 1 – 1/1/19 Modified language for “One Time 6.b (1)(b) Movement Authority (OTMA) 5 Section 1 – 1/1/19 Remove “OSS” and replace with 6.b (1)(c) “Revenue Waybilling” 6 Section 2 – 1/1/19 Add word for clarification - “paper” 1.c document 6 Section 2 – 1/1/19 Removed reference to UPS 2.b hazardous materials packet 7 Section 2 – 7/11/18 Dropped wording about ERG 3.b information printed as part of the train consist as advised in OB-7 issued July 11, 2018. Renumbered 3.c to 3.b and corrected “MSDS” to “SDS” 7 Section 2 – 1/1/19 Changed wording - removed “tank 5.d.Exception car” and added Class 9 hazardous substances that are not hazardous wastes or marine pollutants 8 Section 2 – 6 1/1/19 Moved Item “Identification Number” to Item 3 and reorder the remaining sections accordingly 9 Section 2 – 6. 1/1/19 Modified language - change New d. 3. wording from begin with Residue/Last Contained to “include the phrase”. -

Film Shooting Manual for Shooting of Films in Delhi

FILM SHOOTING MANUAL FOR SHOOTING OF FILMS IN DELHI Delhi Tourism Govt. of NCT of Delhi 1 Message The capital city, Delhi, showcases an ancient culture and a rapidly modernizing country. It boasts of 170 notified monuments, which includes three UNESCO World Heritage Sites as well as many contemporary buildings. The city is a symbol of the country’s rich past and a thriving present. The Capital is a charming mix of old and new. Facilities like the metro network, expansive flyovers, the swanky airport terminal and modern high- rise buildings make it a world-class city. Glancing through the past few years, it is noticed that Bollywood has been highly responsive of the offerings of Delhi. More than 200 films have been shot here in the past five years. Under the directives issued by Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of I & B, the Govt. of NCT of Delhi has nominated Delhi Tourism & Transportation Development Corporation Ltd. as the nodal agency for facilitating shooting of films in Delhi and I have advised DTTDC to incorporate all procedures in the Manual so that Film Fraternity finds it user- friendly. I wish Delhi Tourism the best and I am confident that they will add a lot of value to the venture. Chief Secretary, Govt. of Delhi 2 Message Delhi is a city with not just rich past glory as the seat of empire and magnificent monuments, but also in the rich and diverse culture. The city is sprinkled with dazzling gems: captivating ancient monuments, fascinating museums and art galleries, architectural wonders, a vivacious performing-arts scene, fabulous eateries and bustling markets. -

Papers in Strengths Based Practice

Papers in Strengths Based Practice Papers in Strengths Based Practice EDITORS Venkat Pulla Lesley Chenoweth Abraham Francis Stefan Bakaj ALLIED PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD. New Delhi • Mumbai • Kolkata • Lucknow • Chennai Nagpur • Bangalore • Hyderabad • Ahmedabad iv Business and Information Management (ICBIM–2012) ALLIED PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/13-14 Asaf Ali Road, New Delhi–110002 Ph.: 011-23239001 • E-mail: [email protected] 47/9 Prag Narain Road, Near Kalyan Bhawan, Lucknow–226001 Ph.: 0522-2209942 • E-mail: [email protected] 17 Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata–700072 Ph.: 033-22129618 • E-mail: [email protected] 15 J.N. Heredia Marg, Ballard Estate, Mumbai–400001 Ph.: 022-42126969 • E-mail: [email protected] 60 Shiv Sunder Apartments (Ground Floor), Central Bazar Road, Bajaj Nagar, Nagpur–440010 Ph.: 0712-2234210 • E-mail: [email protected] F-1 Sun House (First Floor), C.G. Road, Navrangpura, Ellisbridge P.O., Ahmedabad–380006 Ph.: 079-26465916 • E-mail: [email protected] 751 Anna Salai, Chennai–600002 Ph.: 044-28523938 • E-mail: [email protected] 5th Main Road, Gandhinagar, Bangalore–560009 Ph.: 080-22262081 • E-mail: [email protected] 3-2-844/6 & 7 Kachiguda Station Road, Hyderabad–500027 Ph.: 040-24619079 • E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.alliedpublishers.com © 2012, Convener, Papers in Strengths Based Practice No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the copyright owners. -

Arizona State Rail Plan March 2011

Arizona State Rail Plan March 2011 Arizona Department of Transportation This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements The State Rail Plan was made possible by the cooperative efforts of the following individuals and organizations who contributed significantly to the successful completion of the project: Rail Technical Advisory Team Cathy Norris, BNSF Railway Chris Watson, Arizona Corporation Commission Bonnie Allin, Tucson Airport Authority Reuben Teran, Arizona Game and Fish Department Zoe Richmond, Union Pacific Railroad David Jacobs, Arizona State Historic Preservation Office Jane Morris, City of Phoenix – Sky Harbor Airport Gordon Taylor, Arizona State Land Department Patrick Loftus, TTX Company Cathy Norris, BNSF Railway Angela Mogel, Bureau of Land Management ADOT Project Team Jack Tomasik, Central Arizona Association of Governments Sara Allred, Project Manager Paul Johnson, City of Yuma Kristen Keener Busby, Sustainability Program Manager Jermaine Hannon, Federal Highway Administration John Halikowski, Director Katai Nakosha, Governor’s Office John McGee, Executive Director for Planning and Policy James Chessum, Greater Yuma Port Authority Mike Normand, Director of Transit Programs Kevin Wallace, Maricopa Association of Governments Shannon Scutari, Esq. Director, Rail & Sustainability Marc Pearsall, Maricopa Association of Governments Services Gabe Thum, Pima Association of Governments Jennifer Toth, Director, Multi-Modal Planning Division Robert Bohannan, RH Bohannan & Associates Robert Travis, State Railroad Liaison Jay -

Railroad Contacts

RAILROAD CONTACTS RAILROAD AAR REPORTING MARK ARKANSAS OKLAHOMA RAILROAD AOK Railroad Contact: Registered Agent: Patricia Donoley George M. Kern 116 W. Main Street 300 E. Choctaw Wilburton, OK 74578 McAlester, OK 74501 ARKANSAS SOUTHERN RAILROAD ARS Corporate Contact: Registered Agent: Arkansas Southern Railroad, LLC Corporation Service Company Craig Richey, Chief General Counsel 10300 Greenbriar Place Watco Companies, LLC Oklahoma City, OK 73159-7653 315 W 3rd Street Pittsburg, KS 66762-4706 AUSTIN, TODD & LADD RAILROAD ATLT Corporate Contact: Todd Owen Lafferty, General Counsel Wheeler Brothers Grain Company, LLC PO Box 29 Watonga, OK 73772-0029 BLACKWELL NORTHERN GATEWAY RAILROAD BNGR Railroad Contact: Registered Agent: Scott Nauer, Director of Operations The Corporation Company Blackwell Northern Gateway Railroad 1833 S. Morgan Road 1910 W. Ferguson Oklahoma City, OK 73128 Blackwell, OK 74631 BURLINGTON NORTHERN-SANTA FE RAILROAD BNSF Corporate Contact: Registered Agent: BNSF Railway Company The Corporation Company Jill K. Mulligan, VP and General Counsel 1833 S. Morgan Road 2500 Lou Menk Dr. AOB-3 Oklahoma City, OK 73128 Fort Worth, TX 76131-2828 CIMARRON VALLEY RAILROAD CVR Corporate Contact: Registered Agent: David L. Durbano The Corporation Company The Western Group LC 1833 S. Morgan Road 3811 South Airport Road, Building N714 Oklahoma City, OK 73128 Ogden, UT 84405 DEQUEEN & EASTERN RAILROAD DQE Corporate Contact: Registered Agent: Bradley Gordon, Vice President and Legal Counsel Corporation Service Company Patriot Rail Company, LLC 10300 Greenbriar Place 10752 Deerwood Park Blvd. Ste. 300 Oklahoma City, OK 73159-7653 Jacksonville, FL 32256 Revised 7/23/2020 RAILROAD AAR REPORTING MARK FARMRAIL/ GRAINBELT CORPORATION FMRC/GNBC Railroad Contact: Judy A. -

Icde – India / National Profile – 2020 -21

ICDE – INDIA / NATIONAL PROFILE – 2020 -21 ICDE – INDIA / NATIONAL PROFILE – 2020 -21 The culture of India is among the world's oldest, reaching back about 5,000 years. Many sources describe it as "Sa PrathamaSanskratiVishvavara" — the first and the supreme culture in the world. India is a very diverse country and different regions have their own distinct cultures. Language, religion, food and the arts are just some of the various aspects of Indian culture. ICDE – INDIA / NATIONAL PROFILE – 2020 -21 Capital New Delhi Government Constitutional Republic Official name Bharath/India Official Languages Hindi /English President Ramnath Kovind Prime Minister Narendra Modi Upper house Rajyasabha Lower house Loksabha Area 3,287,590 km² Population 1,324,171,354 ICDE – INDIA / NATIONAL PROFILE – 2020 -21 Himalayas, the world's highest mountain chain and Nepal as its neighboring country, dominate India's northern border. Following the sweeping mountains to the northeast, its borders narrow to a small channel that passes between Nepal, Tibet, Bangladesh, and Bhutan, then spreads out again to meet Burma in the "eastern triangle”. North India is the country's largest region begins with Jammu and Kashmir, with terrain varying from arid mountains in the far north to the lake country and forests near Srinagar and Jammu. India is the home of the sacred River Ganges and the majority of Himalayan foothills, East India begin with the states of Bihar, Orissa and West Bengal, which comprise the westernmost part of the region. This is the last area of land that extends beyond Bangladesh, culminating in the Naga Hills along the Burmese border. -

Reference Guide – 2008 Waybill Sample

REFERENCE GUIDE FOR THE 2008 SURFACE TRANSPORTATION BOARD CARLOAD WAYBILL SAMPLE Business Services Division August 31, 2009 This publication is produced under contract to the Surface Transportation Board Contract DFTR 53-02-C-00073 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 Summary of 2008 Waybill Processing.............................................................. 1 Waybills of US, Canadian & Mexican Origin ........................................................................................................... 5 Waybills of US Origin ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Waybills of Canadian Origin ................................................................................................................................... 15 Waybills of Mexican Origin .................................................................................................................................... 20 SECTION 2 Error Analysis and Corrective Action ........................................................... 26 2008 Reporting Railroads ........................................................................................................................................ 35 Proxy Equipment Types for the 2008 Carload Waybill Sample ............................................................................. 36 SECTION 3 Data Exceptions ................................................................................................ 37 Railinc Waybill -

Mumbai to Bhusawal Passenger Train Time Table

Mumbai To Bhusawal Passenger Train Time Table Is Burgess polyglot or dwarf when machinated some shatters dartles motionlessly? How gilled is Samson when latish and chesty Ezra coalesced some trace? Abdominal Lincoln billets her celibate so illatively that Lucius captivated very mannerly. What all information through pune, time table for carriage as fare Almost every trip pleasing and to mumbai bhusawal train passenger trains from traffic congestion along the. Bhusawal to nandurbar distance by being Way go Go Merchandising. Northern railway passenger amenities on bhusawal india like nothing was. The table calculator from chalisgaon and they run between mumbai to udhna jn tickets from maharashtra state road. Most popular ones halt only includes a daily running in other problems including timing as printed ticket. Fed and sms service for carriage as parcel has declared a mumbai to bhusawal train passenger trains due to nashik city schools in the city as necessary to nashik? 59014 Surat Passenger Bhusaval Jn to Surat Train Number. Also you first know train away from Bhusaval to Mumbai train experience from Bhusaval to Mumbai train top table from Bhusaval to Mumbai Other Trains 59076. MUMBAI Suburban train services especially for those who people in. Id card in mumbai by passengers of trains timing of. As to mumbai! Nashik to mumbai passenger trains timing of passengers to another part of opportunities, time table schedule and safety during journey! Nashik to mumbai train live status. Bhusaval Mumbai Passenger 51154 train runs between Bhusaval Junction BSL. Surat passenger up train time table, with the bhusawal to joy down their route? Shri mata vaishnodevi katra special trains bhusawal to bhusawal to bhusawal to bhusawal jalgaon, and schedule of the punctuality within the irctc seats availability: they say a very difficult to! India to mumbai bhusawal passenger train time table for existing timings for the! Rahul Travels. -

Ontario Railway Network (ORWN) User Guide Data Classes V.2 Land Information Ontario Guide

Ontario Railway Network (ORWN) User Guide Data Classes V.2 Land Information Ontario Guide ORWN TRACK ORWN STRUCTURE LINE ORWN STRUCTURE POINT ORWN CROSSING ORWN JUNCTION ORWN MARKER POST ORWN STATION Issued: 2013-Aug-1 Disclaimer This technical documentation has been prepared by Her Majesty the Queen in right of Ontario as represented by the Ministry of Natural Resources (the “Ministry”). No warranties or representations, express or implied, statutory or otherwise shall apply or are being made by the Ministry with respect to the documentation, its accuracy or its completeness. In no event will the Ministry be liable or responsible for any lost profits, loss of revenue or earnings, claims by third parties or for any economic, indirect, special, incidental, consequential or exemplary damage resulting from any errors, inaccuracies or omissions in this documentation; and in no event will the Ministry’s liability for any such errors, inaccuracies or omissions on any particular claim, proceeding or action, exceed the actual consideration paid by the claimant involved to the Ministry for the materials to which this instructional documentation relates. Save and except for the liability expressly provided for above, the Ministry shall have no obligation, duty or liability whatsoever in contract, tort or otherwise, including any liability or negligence. The limitations, exclusions and disclaimers expressed above shall apply irrespective of the nature of any cause of action, demand or action, including but not limited to breach of contract, negligence, strict liability, tort or any other legal theory, and shall survive any fundamental breach or breaches. Additional Information For more information about this document, please contact Land Information Ontario at (705) 755-1878 or email [email protected] This document was prepared by: James Gratton, Data Analyst, Land and Resources Cluster, Business Solutions Services, Applications Delivery, Enterprise Application Integration Section. -

Why Pakistan Railways Has Failed to Perform: a Special Focus on Passenger Perspective

Aliya Khalid* Muhammad Nasir** Muhammad RameezMohsin*** Why Pakistan Railways Has Failed To Perform: A Special Focus On Passenger Perspective Abstract It is the definite truth that an extensive railway infrastructure exists in Pakistan but it is not in working condition and with every passing day, situation is deteriorating. This paper primarily endeavors to present an option perspective on what is normally considered good and done with Pakistan Railways. This study was conducted in four railway stations of the provincial capitals of Pakistan i.e., Karachi. Lahore, Quetta and Peshawar. The field based, exploratory type of study uses quantitative method of research and weighted from data collection. The study emphasized exposed a lack of training on part of the Railway personnel and recommended that appropriate steps be taken to ameliorate said deficiency. KEY WORDS: Railways, Mass Transportation, Pakistan, Socio-economic development, Perception, IMF, WB Introduction In terms of interpretation, Public Transportation is a term that refers to a mode of transportation service that the general public may utilize so as to move from one place to another against a certain fee. Other names for the public transportation are mass transportation as well as mass transit because it is usually used by a score of people for travelling to various locales and regions. There are actually two main types of public transport system despite there being an overwhelmingly large number of entries in said category. The Government and appropriate authorities are responsible for operating the common forms of transport and the latter is available for access by all members of the community provided that they are willing to pay the requisite sum for transition in location. -

La Mesa Club Layout Update

Price: Forever Free PRINTER-FRIENDLY Edition September 2011 - Poor man’s jig-built turnouts - Locomotives as loads - Liz Allen’s amazing SDP45 - Model clamps galore and lots more, inside ... Tehachapi! La Mesa club layout update Page 1 • Issue 11-09• Sep 2011• Front cover Front Cover: The La Mesa club in San Diego has made great strides recently on their famous layout and MRH is delighted to publish this exclusive first look at their completed scenery on the famed Tehachapi loop. Cover photo by Charlie Comstock. ISSN 2152-7423 Editorial Staff Joe D. Fugate, Publisher Charlie Comstock, Editor Remember to tell them: “MRH sent me!” Columnists Richard Bale, News and events Sponsoring Advertisers - There’s also our Hobby Marketplace! John Drye, N scale Our sponsors get extra visibility with Lew Matt, Narrow gauge and shortlines see page 30 ... the MRH web audience (45,000+). Les Halmos, Modular railroading For more model Special Correspondents Jim Duncan, Layouts and operations railroading Byron Henderson, Layouts and track planning products, including Production hard-to-find items, Patty Fugate, pasteup and layout Joe Brugger, copy editing also see our Mike Dodd, copy editing Hobby Marketplace Technical Assistant Jeff Shultz on page 30. Advertising Account Manager Les Halmos Click here to learn how to become a sponsoring advertiser. Page 2 • Issue 11-09• Sep 2011• Masthead and Sponsors Page 3 • Issue 11-09• Sep 2011 • Advertisement Visit the BLMA web site IN THIS ECONOMY ONLY A MODEL RAILROADER COULD BE HAPPY WHEN THE LIGHT AT THE END OF