Download (3504Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal and Regulatory Approaches to Rehabilitation Planning

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Legal and Regulatory Approaches to Rehabilitation Planning: A Concise Overview of Current Laws and Policies Addressing Access to Rehabilitation in Five European Countries Aditi Garg 1,*, Dimitrios Skempes 1,2 and Jerome Bickenbach 1,2 1 Department of Health Sciences and Medicine, University of Lucerne, Frohburgstrasse 3, 6002 Luzern, Switzerland; [email protected] (D.S.); [email protected] (J.B.) 2 Swiss Paraplegic Research, Guido A. Zäch Str. 4, 6207 Nottwil, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-519-239-5295 Received: 6 May 2020; Accepted: 5 June 2020; Published: 18 June 2020 Abstract: Background: The rising prevalence of disability due to noncommunicable diseases and the aging process in tandem with under-prioritization and underdevelopment of rehabilitation services remains a significant concern for European public health. Over recent years, health system responses to population health needs, including rehabilitation needs, have been increasingly acknowledging the power of law and formal written policies as strategic governance tools to improve population health outcomes. However, the contents and scope of enacted legislation and adopted policies concerning rehabilitation services in Europe has not been synthesized. This paper presents a concise overview of laws and policies addressing rehabilitation in five European countries. Methods: Publicly available laws, policies, and national action plans addressing rehabilitation issues of Sweden, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom were reviewed and descriptive documents analyzed. Actions found in national health policies were also evaluated for compliance with the key recommendations specified in the World Health Organization’s Rehabilitation 2030: Call for Action. -

Embedded Generation Connection Incentives for Distribution Network Operators

EMBEDDED GENERATION CONNECTION INCENTIVES FOR DISTRIBUTION NETWORK OPERATORS Report Number: K/EL/00286/REP URN 02/1148 Contractor Ilex Energy Consulting Prepared by Peter Williams Stephen Andrews The work described in this report was carried out under contract as part of the DTI Sustainable Energy Programmes. The views and judgements expressed in this report are those of the contractor and do not necessarily reflect those of the DTI. First Published 2002 © Crown copyright Disclaimer While ILEX considers that the information and opinions given in this work are sound, all parties must rely upon their own skill and judgement when making use of it. ILEX does not make any representation or warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this report and assumes no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. ILEX will not assume any liability to anyone for any loss or damage arising out of the provision of this report. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I 1. REVIEW OF THE EXISTING OBLIGATIONS ON DISTRIBUTION NETWORK OPERATORS 1 2. REVIEW OF DNO PRACTICE 9 3. INTRODUCTION OF THE UTILITIES ACT 2000 21 4. DNO INCENTIVES - PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS 36 ANNEX A: DNO QUESTIONNAIRE 60 [This page is intentionally blank] INTRODUCTION This is a final report on the work undertaken by ILEX on the ‘Connection Incentives for Distribution Network Operators’ project - commissioned by the DTI as part of the New and Renewable Energy Programme. This work covers the tasks of the project as described in the original proposal and subsequently formalised under contract between ILEX and ETSU1. -

Health Service Commissioners Act 1993

Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Health Service Commissioners Act 1993. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) ELIZABETH II c. 46 Health Service Commissioners Act 1993 1993 CHAPTER 46 An Act to consolidate the enactments relating to the Health Service Commissioners for England, for Wales and for Scotland with amendments to give effect to recommendations of the Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission. [5th November 1993] F1Be it enacted by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— Annotations: Amendments (Textual) F1 Act repealed (S.) (23.10.2002) by 2002 asp 11, s. 25(1), Sch. 6 para. 14 (with savings in Sch. 7); S.S.I. 2002/467, art. 2 Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act applied (1.4.1999) by S.I. 1999/686, art. 5(1), Sch. Pt. II Act applied (with modifications)(1.4.1999) by S.I. 1999/726, art. 5(1)(2), Sch. Pt. II Act applied (6.4.2001) by S.I. 2001/137, art. 5, Sch. Pt. II Act applied (S.) (31.3.2002) by S.S.I. 2002/103, art. 6, Sch. Pt. II (with art. 4(4)) Act applied (S.) (27.6.2002) by S.S.I. 2002/305, art. -

Scotland Act 2016 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 22 July 2021

Status: Point in time view as at 01/12/2017. This version of this Act contains provisions that are not valid for this point in time. Changes to legislation: Scotland Act 2016 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 22 July 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) Scotland Act 2016 2016 CHAPTER 11 An Act to amend the Scotland Act 1998 and make provision about the functions of the Scottish Ministers; and for connected purposes. [23rd March 2016] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— PART 1 CONSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS The Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government 1 Permanence of the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government In the Scotland Act 1998 after Part 2 (the Scottish Administration) insert— “PART 2A PERMANENCE OF THE SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT AND SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT 63A Permanence of the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government (1) The Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government are a permanent part of the United Kingdom's constitutional arrangements. (2) The purpose of this section is, with due regard to the other provisions of this Act, to signify the commitment of the Parliament and Government of the United Kingdom to the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government. -

Utilities Act 2000 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 25 September 2021

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: Utilities Act 2000 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 25 September 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Utilities Act 2000 2000 CHAPTER 27 PART I NEW REGULATORY ARRANGEMENTS 1 Gas and Electricity Markets Authority. (1) There shall be a body corporate to be known as the Gas and Electricity Markets Authority (in this Act referred to as “the Authority”) for the purpose of carrying out— (a) functions transferred to the Authority from the Director General of Gas Supply and the Director General of Electricity Supply; and (b) the other functions of the Authority under this Act. (2) The functions of the Authority are performed on behalf of the Crown. (3) The offices of Director General of Gas Supply and Director General of Electricity Supply are abolished. (4) Schedule 1 has effect with respect to the Authority. Commencement Information I1 S. 1 wholly in force at 1.10.2001; s. 1 not in force at Royal Assent see s. 110(2); s. 1(1)(2)(4) in force at 1.11.2000 by S.I. 2000/2917, art. 2; s. 1(3) in force at 1.10.2001 by S.I. 2001/3266, art. 2, Sch. (subject to transitional provisions in arts. 3-20) F12 Gas and Electricity Consumer Council. -

How Can the Lens of Human Rights Provide a New Perspective on Drug Control and Point to Different Ways of Regulating Drug Consumption?

How can the lens of human rights provide a new perspective on drug control and point to different ways of regulating drug consumption? A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Melissa L. Bone School of Law Table of Contents Index of Tables……………………………………………………………………..….5 Table of Cases………………………………………….………………………………6 Table of Statutes, Treaties and Legislative Instruments……………………………....10 List of Abbreviations…………………………………………………………………15 Abstract………………………………………………...…………………………….18 Candidate’s Declaration and Copyright Statement…………………………………...19 Acknowledgements…………………………………...……………………………...20 Introduction………………………………………………………………..…………22 Chapter 1: Understanding the origin and value of human rights and psychoactive consumption………………………………………………………………………….32 1.1 What are human rights and where have they come from?………..……………….33 1.2 Human right foundations and the question of importance…………...……………36 1.3 The grounds for human rights…………………………………………….………42 1.3.1 ‘The universalist challenge’…………………………………………..46 1.4 The origin and value of human psychoactive consumption……………………….49 1.5 Conclusion……………………………………………………………..…………54 Chapter 2: Understanding how human rights can address the drug policy binary: the conflict between the interests of the State and the interests of the individual………….55 2.1 Defining ‘the State’……………………………………………………...………..56 2.2 Identifying four ‘typical philosophical positions and the binary which underpins them……………………………………………………………….………………….62 -

Key Dates in Tobacco Regulation 1962 — 2020

Key dates in tobacco regulation 1962 — 2020 16 Further information about the early history of tobacco is available at: www.tobacco.org/History/history.html 1962 The first Royal College of Physicians (RCP) report, "Smoking and Health", was published. It received massive publicity. The main recommendations were: restriction of tobacco advertising; increased taxation on cigarettes; more restrictions on the sales of cigarettes to children, and smoking in public places; and more information on the tar/nicotine content of cigarettes. For the first time in a decade, cigarette sales fell. The Tobacco Advisory Committee (subsequently Council, and now known as the Tobacco Manufacturers’ Association) - which represents the interests of the tobacco industry - agreed to implement a code of advertising practice for cigarettes which was intended to take some of the glamour out of cigarette advertisements. The code was based on the former ITA code governing cigarette advertisements on TV (before they were removed in 1964, with the co-operation of the ITA) 1964 The US Surgeon General produced his first report on "Smoking and Health". Its conclusions corroborated those of the RCP and the US Surgeon General has produced annual reports since 1967 on the health consequences on smoking. Doll and Hill published the results of a nationwide prospective survey on "mortality in relation to smoking: 10 years' observations in British Doctors". Between 1951 and 1964 about half the UK's doctors who smoked gave up and there was a dramatic fall in lung cancer incidence among those who gave up as opposed to those who continued to smoke. 1965 After considerable debate, the government used the powers vested in it under the terms of the 1964 Television Act to ban cigarette advertisements on television. -

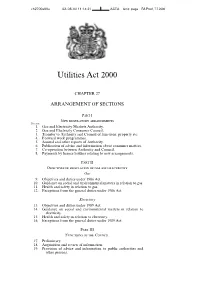

Utilities Act 2000

ch2700a00a02-08-00 11:14:31 ACTA Unit: paga RA Proof, 7.7.2000 Utilities Act 2000 CHAPTER 27 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Part I New regulatory arrangements Section 1. Gas and Electricity Markets Authority. 2. Gas and Electricity Consumer Council. 3. Transfer to Authority and Council of functions, property etc. 4. Forward work programmes. 5. Annual and other reports of Authority. 6. Publication of advice and information about consumer matters. 7. Co-operation between Authority and Council. 8. Payments by licence holders relating to new arrangements. Part II Objectives of regulation of gas and electricity Gas 9. Objectives and duties under 1986 Act. 10. Guidance on social and environmental matters in relation to gas. 11. Health and safety in relation to gas. 12. Exceptions from the general duties under 1986 Act. Electricity 13. Objectives and duties under 1989 Act. 14. Guidance on social and environmental matters in relation to electricity. 15. Health and safety in relation to electricity. 16. Exceptions from the general duties under 1989 Act. Part III Functions of the Council 17. Preliminary. 18. Acquisition and review of information. 19. Provision of advice and information to public authorities and other persons. ch2700a01a02-08-00 11:14:31 ACTA Unit: paga RA Proof, 7.7.2000 ii c. 27 Utilities Act 2000 Section 20. Provision of information to consumers. 21. Power to publish advice and information about consumer matters. 22. Complaints. 23. Investigations. 24. Provision of information to Council. 25. Publication of notice of reasons. 26. Provision of information by Council to Authority. 27. Sections 24 to 26: supplementary. -

![The Energy Bill [HL] 6 MAY 2004 Bill 93 of 2003-2004](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4573/the-energy-bill-hl-6-may-2004-bill-93-of-2003-2004-1204573.webp)

The Energy Bill [HL] 6 MAY 2004 Bill 93 of 2003-2004

RESEARCH PAPER 04/36 The Energy Bill [HL] 6 MAY 2004 Bill 93 of 2003-2004 The Energy Bill is in Five Parts. Provisions in Part 2 of the Bill relating to the Civil Nuclear Industry and the Nuclear Decommissioning Agency (NDA) are dealt with in a separate paper (RP 04/37) Part 1 introduces a duty to ensure security and integrity of supply and to make annual reports to Parliament on new energy sources under the Sustainable Energy Act 2003, and on energy efficiency. Part 3 of the Energy Bill relates to the development of offshore renewable energy resources and the establishment of a mutually recognisable system of Renewable Obligation Certificates in Northern Ireland. It also includes a strategy for microgeneration and provision for a Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation. Part 4 of the Bill relates to energy regulation issues, principally the introduction of Great Britain wide electricity trading and transmission arrangements, known as BETTA. Part 5 relates to miscellaneous and supplemental provisions. Most of the Bill’s content relates to reserved matters, and with exceptions, applies to the whole of the United Kingdom. Brenda Brevitt SCIENCE AND ENVIRONMENT SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY RESEARCH PAPER 04/36 Recent Library Research Papers include: 04/21 Promotion of Volunteering Bill [Bill 18 of 2003-04] 03.03.04 04/22 The Justice (Northern Ireland) Bill [HL] [Bill 55 of 2003-04] 04.03.04 04/23 Poverty: Measures and Targets 04.03.04 04/24 The Cardiac Risk in the Young (Screening) Bill [Bill 19 of 2003-04] 10.03.04 04/25 The Christmas Day -

Health and Care Bill Explanatory Notes

HEALTH AND CARE BILL EXPLANATORY NOTES What these notes do These Explanatory Notes relate to the Health and Care Bill as introduced in the House of Commons on 6 July 2021 (Bill 140). • These Explanatory Notes have been prepared by the Department of Health and Social Care in order to assist the reader of the Health and Care Bill and to help inform debate on it. They do not form part of the Health and Care Bill and have not been endorsed by Parliament. • These Explanatory Notes explain what each part of the Health and Care Bill will mean in practice; provide background information on the development of policy; and provide additional information on how the Health and Care Bill will affect existing legislation in this area. • These Explanatory Notes might best be read alongside the Health and Care Bill. They are not, and are not intended to be, a comprehensive description of the Health and Care Bill. Bill 140–EN 58/2 Table of Contents Subject Page of these Notes Overview of the Health and Care Bill 10 Policy Background 11 Merging NHS England, Monitor and NHS Trust Development Authority 11 Mandate and financial directions to NHS England 12 Funding for service integration 14 The NHS Payment Scheme 14 Capital spending limits over Foundation Trusts 15 New NHS Trusts 16 Integrated Care Boards and Integrated Care Partnerships 17 Triple Aim 17 Duty to Cooperate 18 Joint Appointments 18 Joint Committees 18 Collaborative Commissioning 18 Secretary of State’s duty to report on workforce systems 19 Abolition of LETBs 20 Information 20 Secretary of State -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 760 Monday No. 110 2 March 2015 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Questions Parliament: Conventions ...........................................................................................................................................1 Defence: Strategic Defence and Security Review.................................................................................................5 Tehran: British Embassy..........................................................................................................................................7 Astute-class Submarines............................................................................................................................................9 Health Service Commissioner for England (Complaint Handling) Bill First Reading ...........................................................................................................................................................12 Warm Home Discount (Miscellaneous Amendments) Regulations 2015 Motion to Approve..................................................................................................................................................12 Social Security Benefits Up-rating Order 2015.......................................................................................................12 Mesothelioma Lump Sum Payments (Conditions and Amounts) (Amendment) Regulations 2015..........................................................................................................................................................12 -

Chapter I About the Judiciary

William Michael Ramsden Student ID: UM2743HLS6759 Ascertaining the Boundary of Legitimate Judicial Intervention A Final Dissertation Presented to The Academic Department of School of Social and Human Studies In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Ph.D Link to the University: hhp://www.aiu.edu A I U Ascertaining the Boundary of Legitimate Judicial Intervention ‘Sections 3 and 4 of the Human Rights Act: ascertaining the boundary of legitimate judicial intervention’ Index Chapter 1 Introduction and Overview 3-12 Chapter 2 Human Rights background and Context 13-54 Chapter 3 Freedom and liberty 55-67 Chapter 4 Public Authority uncertainty and Section 6(1) 68-150 Chapter 5 Enforcement under the Human Rights Act. 151-183 Chapter 6 Changing Constitutional Mores. 184-199 Chapter 7 Human Rights Uncertainty 200-239 Chapter 8 Anti-Terrorism Policies and the Open Society 238-353 Chapter 9 SIAT A Case Study 356-385 Chapter 10 The Dialogue Model 386-430 Chapter 11 Descriptive, analytical & normative arguments 431-433 Chapter 12 Conclusion 434-433 Bibliography 434-460 A Dissertation by William Michael Ramsden 1 ‘Sections 3 and 4 of the Human Rights Act: ascertaining the boundary of legitimate judicial intervention’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A special thanks to my son Michael Philip Ramsden LL.B (Hons), LL.M, who relentlessly read and re-read my thesis to which I am eternally grateful for his thoughts and comments. -and- Equally a special thanks to my younger son Matthew whose patience was beyond compare, as he allowed me time to complete my works at a cost of our extended time together.