Neighbourhoods and the Politics of Scale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zurich on Foot a Walk Through the University District

Universitätsstr. Sonneggstr. Spöndlistrasse 6 Leonhardstrasse 7 Schmelzbergstr. Weinbergstrasse S te r nw a rt st ra ss e Gloriastrasse Tannenstrasse Central 1* 2 Seilergraben Hirschengraben Zähringerstrasse 8 Karl-Schmid-Strasse Schienhutgasse Limmatquai Gloriastrasse 3 14 Künstlergasse Plattenstrasse Rämistrasse Mühlegasse Attenhoferstrasse 5 4 Pestalozzistrasse 13 arkt um e N Florhofgasse 9 U n t e re Z Steinwiesstrasse ä O u b n e e re Z äu n e Plattenstrasse Cäcilienstrasse Heim- platz Freiestrasse 11 Steinwies- 12 platz Hirschengraben Hottingerstrasse 10 Minervastrasse Rämistrasse Aerial photograph, 2013 0 100 200 300 m Zeltweg 1 Polybahn* 5 Bibliothek der Rechtswissenschaf- 9 Rosa Luxemburg 14 Hirschengraben (deer trench) Student express since 1889 ten (Law Library) «Freedom is always the freedom of the Wildlife park at the city walls The very finest in architecture one who thinks differently.» 2 ETH – Swiss Federal Institute of * When the Polybahn is not in operation, Technology 6 focusTerra 10 Johanna Spyri go by foot along Hirschengraben and Students from around 100 countries The secrets of the earth revealed Heidi and Peter the goatherd Schienhutgasse to ETH. Zurich on foot 3 University of Zurich 7 ETH Sternwarte (Astronomical Ob- 11 Schauspielhaus (Theatre) 7 Paving the way for women students servatory) A long tradition of theatre A walk through the A view into space 4 Harald Naegeli 12 Kunsthaus (Museum of Fine Arts) University District Offending citizens with a spray can 8 The hill of villas Plans for an addition Residential «castles» on Mt. Zurich 13 Rechberg Palace A baroque garden for relaxation 1 Polybahn 8 The hill of villas A walk through the University District Duration of the walk: There are four «mountain railways» in the City of Zurich. -

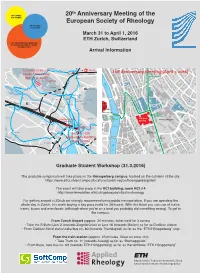

20Th ESR-Meeting Arrival:Layout 1

th 18th SWISS 20 Anniversary Meeting of the SOFT DAYS European Society of Rheology FROM MUD TO BLOOD March 31 to April 1, 2016 ETH Zurich, Switzerland 20th ANNIVERSARY MEETING OF THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF RHEOLOGY Arrival Information Airport Location Graduate 80 Bahnhof Winterthur ESR Anniversary Meeting (April 1, 2016) Student Workshop Oerlikon Bhf. Oerlikon Schaffhausen Tram 10 from Airport (March 31, 2016) Oerlikon ETH Hönggerberg 11 Bolle L i 10/14 m Sonneg ystrasse 69 m S Chäferberg a p 80 t ö n ZH-Milchbuck gstr d l i Meierhofplatz n asse s t S r . t a m p Buchegg- f 69 Milchbuck e platz n b e a 80 Unter- c A1 rück h Wipkingen strass alche-B s W t Universität Zürichberg ra Weinbergstrasse Zürich-Irchel ss Universitätsstrasse Bhf. e Le ZH-Hardturm/ N Altstetten B o City Schaffhauserplatz Oberstrass a e n h u h Bhf. n m a h r Stern ü d Wipkingen o h s f t - le Bhf. Altstetten MAIN r Au war Q a q asse u s u s tstr f d gstr 9/10 a a e STATION i i asse e . elzber Bhf. Hard- r M enstr Schm Tann brücke Bahnhofstr./HB a 31 Bahnhof-Brück Central u Tram Stop: e e r ETH-Zentrum/ Universitätspital Altstetten Tram 6 & 10 Fluntern ETH Main Zurich Main Station from Main Station Universitätsspital (Hauptbahnhof) Building Beatenplatz tquai Aussersihl 6/5 Seiler Limma asse sse Stra R 10 ETH-Zentrum/ graben id- ä Zä m m istr Universitätspital h Karl Sch 6 Central rin asse g Stauffacher erstr Universität Künstler Albisrieden Bhf. -

Kanton Zürich Regionaler Richtplan Stadt Zürich

Kanton Zürich Regionaler Richtplan Stadt Zürich Beschluss des Regierungsrates (RRB Nr. 894 / 2000) INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. ALLGEMEINES ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Einleitung................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Richtplan-Revision .................................................................................................... 1 1.3. Bestandteile/Inhalt ..................................................................................................... 2 1.4. Festsetzung und Verbindlichkeit................................................................................ 2 2. ZIELE DER RÄUMLICHEN ENTWICKLUNG ................................................ 3 2.1. Kantonale Leitlinien................................................................................................... 3 2.2. Die städtischen Ziele der räumlichen Entwicklung ................................................... 4 2.2.1. Zielwandel ................................................................................................................. 4 2.2.2. Wohnen...................................................................................................................... 5 2.2.3. Arbeiten ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.2.4. Verkehr ..................................................................................................................... -

Züri Z'fuess Unterwegs in Aussersihl Und Hard

Hohlstrasse Duttweilerbrücke 19 Hardbrücke Eichbühlstrasse Herdernstrasse18 Bullingerstrasse Bienenstrasse Sihlfeldstrasse Hohlstrasse Ernastrasse 15 17 Bullingerstrasse Sihlhallenstrasse Stüdeli-weg 16 Rolandstr. Lagerstrasse Norastrasse Langstrasse Zinistr. Magnusstrasse Hardstrasse 14 Feldstrasse Zwinglistr. 10 9 Dienerstrasse Herman- Brauerstrasse Stufe Greulich-Str. 12 8 Militärstrasse Agnesstrasse Hohlstrasse Tellstr. Denzler- Albisriederstrasse strasse 11 Erismannstrasse 6 Stauffacherstrasse 7 Badenerstrasse Molken- g strasse e w l e Müllerstrasse s Pflanzschulstrasse r Feldstrasse Kanzleistrasse 5 U Ankerstrasse B ä 13 c k 4 Stauffacherstrassee rs tr a s s e Badenerstrasse Langstrasse Sihlfeldstrasse St. Jakobsstrasse Badenerstrasse 2 denerstra Ba sse 1 Zweierstrasse Ankerstrasse3 e s s a r t rs fe or sd en rm Bi Luftbild 2018 0 100 200 300 400 500m 1 Sihlbrücke 6 Restaurant Sonne 11 Bäckeranlage 16 ABZ-Wohnkolonie und Bullingerplatz Hier wurde geprügelt und gestorben Von der Gewerkschafts- zur Milieubeiz Treffpunkt für stolze Mütter und Väter Der Traum von der ländlichen Idylle 2 Behindertenwerk St. Jakob 7 Kaserne 12 Hotel Greulich 17 Hardau Beste Qualität seit über 100 Jahren Die Soldaten sind schon lange weg Das Architektur-Highlight im Kreis 4 Das «Klein-Manhattan» Zürichs 3 Dreieck 8 Radio LoRa 13 Lochergut 18 Herdernstrasse 56 Züri z’Fuess Modernes Zusammenleben Sendungen in 20 Sprachen Heiss begehrte Wohnungen Rechts wird geschlachtet, links 5 getschuttet Unterwegs in Aussersihl 4 Kanzlei 9 Café Memphis 14 Erismannhof 19 Buslinie 31 Kino, Pétanque und Flohmarkt Wo Gina auf den Heini wartete Hier wird noch mit Holz geheizt und Hard Der Schmelztiegel der Nationen 5 Helvetiaplatz und Volkshaus 10 Missione Cattolica Italiana 15 Güterbahnhof Das linke Zentrum der Stadt Italien für immer im Herzen Einst der modernste in Europa 1 Sihlbrücke 11 Bäckeranlage Zu Fuss in Aussersihl und im Hardquartier Dauer des Spaziergangs: An Stelle der heutigen Sihlbrücke stand zur Zeit der Schlacht von St. -

An Island in Between Two Rivers the Limmat and the Railway Tracks Kreis 5 Kreis 9

FROM AN ISLAND IN BETWEEN INSIDE OUT TWO RIVERS MASTER THESIS THE LIMMAT AND THE THEME A HS19 RAILWAY TRACKS DARCH, ETH Zürich KREIS 5 KREIS 9 Studio Anne Lacaton 5 I INTRODUCTION 7 II CONTEXT Perimeter Presentation Photo essay Morphology and buildings Transformation Historical context Maps of Zürich - public transportation Maps of Zürich - Cadastres 74 III TASK 75 IV INFORMATION Process Cycle Deliverables Schedule 78 V INTEGRATED DISCIPLINES 85 VI APPENDIX I INTRODUCTION AN ISLAND IN BETWEEN TWO RIVERS THE LIMMAT AND THE RAILWAY TRACKS, KREIS 5 KREIS 9 The Master Topic A deals with contemporary urban conditions and challenges of one of Zurich’s most heterogeneous territories, attractive for new development at once. Here, we explore the optimal ways to live in the city while having an optimal use of ground and everything existing. The meaning of overused terms such as “densification” or “transformation” in a context of continuous use and re-use of rare or contested urban soil enter into a critical reflection and position taking. In contrast to a masterplan strategy, the master thesis’ process implies an approach of case by case, from inside out. It is not about defining zoning or rules, but a vision based on the approach of the real situation. It implies an accurate observation in situ, as near as possible to what already exists. Observation, inventory and analysis aim to detect and bring out the existing resources, potentials, opportunities and capacities of each chosen situation. This will constitute a process of transformation based on accumulation and coexistence, with precision and delicacy, far away from a quantified, regular densification or the application of general rules. -

Céline Widmer , Nico Van Der Heiden

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2010 Rescaling and the role of the sub-local scale Widmer, C ; van der Heiden, N Abstract: It is argued that the process of globalisation undermines the nation-state. From the perspective of the rescaling theory, however, the argument would rather be that the spatial dimensions of the state are being reorganized, leading to an upscaling as well as a downscaling of political steering capacities. With global cities becoming more important as nodes of capital accumulation, this results in a greater significance of locational politics for these cities. Although it has been researched how the neoliberal agenda has trickled down from the national level to the scale of the city, literature on rescaling has widely ignored the role of the sub-local scale. We argue that the neighbourhood scale has gained importance in scale politics because city governments increasingly shift neoliberal projects to the sub-local scale. We present empirical evidence on these neighbourhood politics with a detailed case analysis of the city of Zurich. Based on qualitative expert interviews and an in-depth document analysis, we show that the cities’ policy to increase the quality of life in distressed neighbourhoods is closely related to Zurich’s overall economic strategy to promote the attractiveness of the city as a whole. Zurich’s neighbourhood policy primarily focuses on improving the image, rather than the quality of life in these areas by means of physical renewal policy or increasing social service. A negative image of certain areas is seen as hindering the overall competitiveness of the city. -

Langstrasse Road, Neighborhood

LANGSTRASSE ROAD, NEIGHBORHOOD, ETH ZURICH D-ARCH Urban-Think Tank Prof. Alfredo Brillembourg URBAN MODEL? Prof. Hubert Klumpner A Topic Diploma Thesis Spring Semester 2018 ETH ZURICH - DARCH NSL CHAIR OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN DESIGN Urban-Think Tank Prof. Alfredo Brillembourg Prof. Hubert Klumpner ONA Neunbrunnenstrasse 50 8050, Zürich Switzerland CONTACT Melanie Fessel [email protected] +41 (0)44 633 92 20 www.u-tt.arch.ethz.ch LAYOUT Melanie Fessel Julienne Zürn TEXTS Melanie Fessel PHOTOGRAPHY UTT Index Introduction 05 The Context Langstrasse Photo Essay 06 Centtrality 22 District Morphologies 26 Transformations in Langstrasse 30 Learning from Langstrasse 34 Historical Context 46 Cadastres 50 Maps of Zurich (RES Zurich) 58 The Task Introduction 66 Statement 68 The Project Task 71 Information Materials 72 Deliverables Method Evaluation 73 Schedule Tools and References 74 Density 76 Model Perimeter 77 Integrated Disciplines 78 Appendix 82 Langstrasse Langstrasse 4 Introduction Where and what is Langstrasse? This reflects a global phenomenon of cities with exclusive and A road? ‘shrinking’ centers — a transformation that demands critical A quarter within a district? inquiry, and with it, a new form of response by the architecture and design profession. The Quartier of Langstrasse is characterized by different urban morphologies in an area of tension between the Europaallee and Helvetiaplatz. Falling within the district of Kreis 4, the neighbor- THEME hood of Langstrasse showcases a myriad of spatial typologies ranging from existing building stock, new commercial real-estate How can we generate inclusive formats of urban development of the Europaallee, partially dilapidated structures, high-end res- models within the city of Zurich? idential building developments, a variety of commercial activity, as well as the iconic Langstrasse ‘strip’. -

Züri Z'fuess Unterwegs in Oerlikon

Margrit-Rainer-Strasse Fritz-Heeb-Weg 14 Ruedi-Walter-Strasse Otto-Schütz-Weg Brown-Boveri-Str. 12 13 Binzmühlestrasse Birchstrasse 11 E.-Lasker- Schüler-Weg Binzmühlestrasse Therese-Giese- Strasse Regina-Kägi-Str. O b J.-Joyce- e Strasse r w i e 16 s 10 e 15 Affolternsstrasse n s Sophie-Täuber-Str. Bahnhof Zürich t E.-Oprecht- r a Chaletweg Oerlikon sse E.-Canetti- Gertrud-Kurz-Strasse Strasse Platz 9 Ohmstrasse Affolternsstrasse Langwiesstrasse E.-Mann-Weg Edisonstrasse Schulstrasse weg Hofwiesen-strasse Angelika- Wallisellenstrasse Regensbergstrasse Dörflistrasse Franklinstrasse Schwal- benweg 2 Quer- strasse1 Welchog. Tramstrasse Holunderweg S . c r 8 h t s a 3 r f f e h l a a Dorflindenstr. u S s e r s t Schwamendingenstrasse r a H s s e strasse e i d Regensbergstrasse Spielwiesen- e 7 g Saler- Föhrenstrasse Birchsteg ra steig Hofwiesenstrasse b e 5 n 6 Ligusterstr. 4 Birchstrasse B Venusstrasse e Allenmoosstrasse rn Ulmenweg in as tra sse Oerlikonerstrasse Ringstrasse Luftbild 2015 0 100 200 300 400m 1 Colosseum 6 Wäldli 11 Octavo 16 Bahnhof Oerlikon-Nord Revolverküche Eine öffentliche Anlage seit über Wohnungen, Arbeits- und Nistplätze Max-Frisch-Platz und Quartier- 100 Jahren verbindung 2 Grossstadt 12 Toro Sport und Musik 7 Birchsteg Von der Sumpf- zur Bürolandschaft Dank Bahnhof zur Boomtown 3 Dorflinde 13 Aussichtsturm Artilleriebeschuss vor 200 Jahren 8 Kantonsschulen «Hochkamin» mit Überblick überlebt Wo die «Anbauschlacht» begann Züri z’Fuess 14 Wahlenpark 4 Schulhaus Liguster 9 Gustav-Ammann-Park Rot Grün Blau 14 Unterwegs in Oerlikon Sekundarschule mit Schlosspark Wohlfahrtsgarten 15 MFO-Park 5 Geher 10 Regina-Kägi-Hof «Parkhaus» statt Maschinenhalle Kunstskandal und Weltausstellung ABZ und 222 1 Colosseum 9 Gustav-Ammann-Park Zu Fuss in Oerlikon Dauer des Spaziergangs: Das «Kino-Theater Colosseum» war das erste als Kino gebaute Gebäude des Kantons Mitten im Zweiten Weltkrieg, als sein Betrieb Oerli- Dieser Rundgang zeigt Ihnen den historischen und den neu- ca.