DOMESTIC RATS, FLEAS and NATIVE RODENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fleas and Flea-Borne Diseases

International Journal of Infectious Diseases 14 (2010) e667–e676 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Infectious Diseases journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijid Review Fleas and flea-borne diseases Idir Bitam a, Katharina Dittmar b, Philippe Parola a, Michael F. Whiting c, Didier Raoult a,* a Unite´ de Recherche en Maladies Infectieuses Tropicales Emergentes, CNRS-IRD UMR 6236, Faculte´ de Me´decine, Universite´ de la Me´diterrane´e, 27 Bd Jean Moulin, 13385 Marseille Cedex 5, France b Department of Biological Sciences, SUNY at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA c Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA ARTICLE INFO SUMMARY Article history: Flea-borne infections are emerging or re-emerging throughout the world, and their incidence is on the Received 3 February 2009 rise. Furthermore, their distribution and that of their vectors is shifting and expanding. This publication Received in revised form 2 June 2009 reviews general flea biology and the distribution of the flea-borne diseases of public health importance Accepted 4 November 2009 throughout the world, their principal flea vectors, and the extent of their public health burden. Such an Corresponding Editor: William Cameron, overall review is necessary to understand the importance of this group of infections and the resources Ottawa, Canada that must be allocated to their control by public health authorities to ensure their timely diagnosis and treatment. Keywords: ß 2010 International Society for Infectious Diseases. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Flea Siphonaptera Plague Yersinia pestis Rickettsia Bartonella Introduction to 16 families and 238 genera have been described, but only a minority is synanthropic, that is they live in close association with The past decades have seen a dramatic change in the geographic humans (Table 1).4,5 and host ranges of many vector-borne pathogens, and their diseases. -

Alma's Good Trip Mikko Joensuu in Holy Water Hippie Queen of Design Frank Ocean of Love Secret Ingredients T H Is Is T H E M

FLOW MAGAZINE THIS IS THE MAGAZINE OF FLOW FESTIVAL. FESTIVAL. FLOW OF IS THE MAGAZINE THIS ALMA'S GOOD TRIP MIKKO JOENSUU IN HOLY WATER HIPPIE QUEEN OF DESIGN FRANK OCEAN OF LOVE SECRET INGREDIENTS F entrance L 7 OW F L O W the new This is 1 to 0 2 2 0 1 7 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 6–9 12–13 18–21 36–37 Editor 7 7 W Tero Kartastenpää POOL OF ALMA Alma: ”We never really traveled when we were Art Director little. Our parents are both on disability Double Happiness pension and we didn’t IN SHORT have loads of money. Swimming with a Whenever our classmates Designers singer-songwriter. traveled to Thailand Featuring Mikko MINT MYSTERY SOLVED or Tenerife for winter Viivi Prokofjev SHH Joensuu. holidays we took a cruise AIGHT, LOOK to Tallinn. When me and Antti Grundstén 22–27 Anna turned eighteen we Frank Ocean sings about Robynne Redgrave traveled to London with love and God and God and our friends. We stayed for love. Here's what you didn’t five days, drunk.” 40–41 Subeditor know about alt-country star Ryan Adams. Aurora Rämö Alma went to L.A. and 14–15 met everybody. Publisher 34–37 O The design hippie Laura Flow Festival Ltd. 1 1 Väinölä creates a flower ALWAYS altar for yoga people. Lana Del Rey’s American Contributors nightmares, plant cutting 30–33 Hanna Anonen craze, the smallest talk etc. The most quiet places OCEAN OF TWO LOVES Maija Astikainen from abandoned villas to Pauliina Holma Balloon stage finds new UNKNOWN forgotten museums. -

Men's Soccer Page 1/1 Combined Statistics As of Apr 12, 2021 All Games

MEN’S SOCCER 2020-21 GAME NOTES » 2001 & 2011 NCAA Champions » Eight NCAA College Cups ‘20-’21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS THE MATCHUP 7-4-3 overall, 7-2-3 ACC North Carolina (7-4-3) 4-3-1 home, 3-1-2 away Head Coach: Carlos Somoano (Eckerd College, ‘92) Career Record: 135-41-29 (10th season) Fall Record at North Carolina: same Oct. 2 at Duke* (ACCNX) W, 2-0 United Soccer Coaches Rank: No. 16 Oct. 9 Clemson* (ESPNU) W, 1-0 Oct. 18 at Wake Forest* (ACCNX) L, 0-1 ot Charlotte (6-3-1) Oct. 27 at Clemson* (ACCN) T, 3-3 2ot Head Coach: Kevin Langan Nov. 1 NC State* (ACCNX) T, 0-0 2ot United Soccer Coaches Rank: No. 14 Nov. 6 Duke* (ACCN) W, 2-0 2020 ACC Tournament (Chapel Hill) Nov. 15 Clemson (ACCN) L, 0-1 ot THE KICKOFF TAR HEEL RUNDOWN Spring Feb. 25 Liberty (ACCNX) L, 0-1 Matchup: North Carolina (7-4-3) vs. Home 4-3-1 March 5 #4 Pitt* (ACCNX) W, 3-0 Charlotte (6-3-1) Away 3-1-2 March 13 #24 Virginia* (ACCNX) W, 2-0 Rankings: UNC No. 16, Charlotte No. 14 Neutral 0-0-0 March 20 at Syracuse* (ACCNX) T, 0-0 2ot (United Soccer Coaches) vs. United Soccer Coaches ranked foes 3-1-1 March 27 at Notre Dame* (ACCNX) W, 2-1 ot vs. Unranked opponents 4-3-2 Date: Sunday May 2, 2021 April 2 Virginia Tech* (ACCNX) L, 0-1 vs. ACC teams (incl. ACC Tournament) 7-3-3 April 9 at Duke* (ACCNX) W, 1-0 Site: Cary, N.C. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic. -

Biological Observations on the Oriental Rat Flea, Xenopsylla Cheopsis

BIOLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS ON THE ORIENTAL RAT FLEA, Xenopsylla cheopis (ROTHSCHILD), WITH SPECIAL STUDIES ON THE EFFECTS OF THE CHEMOSTERILANT TRIS (1-AZIRIDINYL) PHOSPHINE OXIDE By ROBERT LOOMIS LINKFIELD A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA December, 1966 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to the Chairman of his Supervisory Committee, Dr. J. T. Creighton, Department of Entomology, University of Florida, and the Co-Chairman, Dr. P. B. Morgan, United States Department of Agriculture, for their advice and assistance. For their criticism of the manuscript, appreciation is also expressed to committee members Dr. F. S. Blanton and Mr. W. T. Calaway, and to Dr. A. M. Laessle who read for Dr. Archie Carr. Special thanks are due to Dr. C. N. Smith for the use of facilities at the U.S.D.A. Entomology Research Division Laboratory; to Dr. G. C. LaBrecque for his suggestions and encouragement; and to all the U.S.D.A. staff who assisted. Dr. William Mendenhall, Chairman of the Department of Statistics, assigned Mr. Marcello Pagano to aid in.certain statistical analyses; the Computer Center allotted 15 minutes of computer time. Their cooperation is gratefully acknowledged. Last, but not least, appreciation goes to my wife, Ethel, who typed the preliminary copies of this manuscript and who gave affectionate encouragement throughout the course of this study. ii . TABLE OF CONTENTS . Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. ii LIST OF TABLES V "' LIST OF FIGURES . vii INTRODUCTION . 1 REVIEW OF LITERATURE 5 Chemosterilants 1 . -

2308-0922 (Online)

Bangl. J. Vet. Med. (2015). 13 (2): 1-14 ISSN: 1729-7893 (Print), 2308-0922 (Online) IMPORTANT VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES WITH THEIR ZOONOTIC POTENTIAL: PRESENT SITUATION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVE M. A. H. N. A. Khan Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Science Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh SUMMARY Vector-borne diseases (VBDs) of zoonotic importance are the global threat in the human life and on animal welfare as well. Many vector-borne pathogens (VBPs) have appeared in new regions in the past two decades, while many endemic diseases have increased in incidence. Although introductions and emergence of endemic pathogens are often considered to be distinct processes, many endemic pathogens are actually spreading at a local scale coincident with habitat change. Key differences between dynamics and diseases burden result from increased pathogen transmission following habitat change, deforestation and introduction life into new regions. Local emergence of VBPs are commonly driven by changing in ecology (deforestation, massive natural calamities, civil wares etc.), altered human behavior, enhanced enzootic cycles, pathogen invasion from anthropogenic trade and travel, genomic changes of pathogens to coup up with the new hosts, vectors, and climatic conditions and adaptability in wildlife reservoirs. Once a pathogen is established, ecological factors related to vector and host characteristics can shape the evolutionary selective pressure and result in increased use of people as transmission hosts. West Nile virus (WNV), Nipah virus and Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) are among the best-understood zoonotic vector-borne pathogens (VBPs) to have emerged in the last two decades and showed just how explosive epidemics can be in new regions. -

Delta County Naturalization Name Index

Last Name First Name Middle Name Declaration Second Paper Kahkonen Peter Victor V16,P239 Kahllo Louis V24,P102 Kahlstrom John V7,P436 Kahra Reino V35,P36 V35,P36 Kahra Segred Mrs. V35,P36 V35,P36 Kain Francis V5,P9 1/2 Kain John V8,P101 Kain Mary V19,P165 Kainulainen Eventius B1,F4,P2930 Kainulainen Eventius (Daniel) B5,F2,P2635 B5,F1,P2635 Kaiser John V7,P434 Kaivosoja Saimi Johanna B2,F1,P3144 Kajfasz Teodozya B5,F1,P2584 Kalies John Michael V17,P63 Kalkala Matt V15,P336 Kallarson Johanna Katrina B3,F1,P2101 Kallarson Karl Sigvald V18,P83 Kallarson Karl Sigwald V36,P87 V36,P87 Kallarsson Karl Sigvald V14,P178 Kallem Goreg V7,P7 Kallen George V7,P7 Kallen John V13,P329 Kallerson August Thorwald V31,P37 V31,P37 Kallerson August Thouvald V15,P474 Kallerson Jennie Evelyn B6,F1,P6 Kallerson Karl V18,P51 Kallerson Ragnar Oswald V35,P100 V35,P100 Kallerson Ragnar Oswald V18,P52 Monday, April 01, 2002 Page 236 of 536 Last Name First Name Middle Name Declaration Second Paper Kallersson Karl V38,P6 V38,P6 Kallin John V30,P78 V30,P78 Kallin Peter V26,P55 V26,P55 Kallin Peter V12,P480 Kallio Elma Wilhelmina B1,F4,P2987 Kallio Elma Wilhemiina B4,F4,P2509 B4,F4,P2509 Kallio Johan Victor B1,F3,P2876 Kallio Johan Vihtori B4,F4,P2448 B4,F4,P2448 Kallman And V12,P168 Kallman John V12,P167 Kallman John V7,P267 Kallman John V24,P110 Kallman John V20,P185 Kallman Lars E. V12,P79 Kallorssen Johanna B3,F1,P2101 Kalorssen Karl V38,P6 V38,P6 Kalsen Johannes V11,P171 Kamarainen Seth V15,P420 Kamarainen Seth V19,P92 Kamb Andre V8,P419 kAmerson Andrew V8,P426 Kaminen Oskar V31,P93 V31,P93 Kaminen Oskar V15,P167 Kamovich Mark V17,P284 Kampe Herman V5,P31 Kampe John E. -

Last Name First Name Date of Death Date of Birth Vol.-Page

A B C D E 1 Last name First name Date of death Date of birth Vol.-Page # 2 Laajala Albert "Abbie" 1/12/1980 4/27/1933 L-421, L-535 3 Laajala Esther K 10/27/1997 2/28/1909 L-399, L-553 4 Laakaniemi Catherine V 10/21/2009 10/30/1922 L2-679 5 Laakaniemi Waino J 3/24/1992 2/22/1919 L-427, L-546 6 Laakko Emil 7/13/1983 7/11/1908 L2-178 7 Laakko Hilda 12/1/1969 11/5/1873 L-383, L-534 8 Laakko Samuel Michael 8/28/1980 8/28/1980 L-421, L-535 9 Laakko Vera M 7/6/2002 6/4/1912 L-214, L-215, L-232, L2-382 10 Laakkonen Bernice W (Stolpe) 5/23/2010 8/8/1925 L2-547 11 Laakkonen June (Kallio) 8/22/2003 1930 L-157 12 Laakonen Clarence 7/25/2014 4/26/1929 L2-474 13 Laakso Arvo Oliver 11/14/1998 9/22/1916 L-404, L-527 14 Laakso Bruce 5/6/2014 7/23/1934 L2-494 15 Laakso Edward Erik 4/24/1994 1944 L-342, L-479 16 Laakso Elvira E 6/30/1997 L-387, L-531 17 Laakso Florence 9/10/1977 8/15/1919 L-421 18 Laakso Helen Mildred 9/10/2006 2/26/1923 L2-432 19 Laakso Herbert G 6/12/2004 5/30/1917 L-85 20 Laakso Hilda 7/8/1988 4/17/1907 L-254 21 Laakso Hilma (Manninen) 4/17/2000 7/4/1900 L-273 22 Laakso Jack W 5/24/2002 2/14/1937 L-233 23 Laakso Joel 4/28/1958 2//1887 L-421, L-535 24 Laakso Kustaava 10/12/1955 10/21/1882 L-421, L-535 25 Laakso Rupert "Sam" 7//1987 5/6/1905 L-222, L-254 26 Laakso Tri William A 4/11/1995 L-328 27 Laakso Roger A 2/28/2008 10/8/1935 L-624 28 Laakso Rudolph A 6/9/1905 8/7/1914 L-648 29 Laakso Eva (Tissary) 1/7/1996 L2-84 30 Laakso Toini Perko 7/19/2004 3/12/1918 L-49 31 Laaksonen Bertha H (Nisula) 4/1/2005 1/6/1917 L-2, L-619 32 Laaksonen -

Annual Conference Journals Index to Memoirs

Annual Conference Journals Index to Memoirs Surname First Name Spouse/Father Death/Funeral Date Journal Page Abbott Cleon Frederick Carol 10/6/1994 DC1995 308 Abbott William B. Olive 12/27/1969DC1970 957 Ackerman C.A. UB1946 31 Ackerman Mildred Earl 11/23/1976 DC1977 931 Adams Carl G. Emma Ruth Luzzader 10/2/1981DC1982 1567 Adams Carlos L. Emma Louise Cooper; Flora 8/20/1941 DC1942 550 Kempf Adams Emma Louise Cooper Carlos L. 11/12/1913DC1914 326 Adams Flora Kempf Carlos 8/15/1962DC1963 1135 Adams Robert 12/20/1931 EV1932 55 Ainge Clement Margaret Kershaw 1/30/1948 DC1948 182 Ainge Margaret Kershaw Clement 11/12/1934 DC1935 130 Ainsworth Miriam Ada H. William P 5/28/1954 DC1954 736 Ainsworth William P. Ada; Ethel May Carefoot 10/30/1965DC1966 1046 Alabaster Harriet Ann Bemish J. 10/17/1881 DC1882 37 Albery Paul Franklin Alice Nutting; Mary Barber 11/16/2006 DC2007 219 Willoughby Albig Hattie Loose Orville M. 8/26/1938 EV1939 52 Albig Orville M. Hattie Loose; Ella 2/8/1965 EUB1965 138 Albro Addis Mary Alice Scribner 10/15/1911 DC1912 44 Albro Mary Alice Scribner Addis 8/12/1905 DC1905 184 Allen Adelaide A. Andrews C.B. 11/3/1948 DC1949 448 Allen Alfred Louisa J. Hartwell 1/29/1903 DC1903 40 Allen Bertram E. Ida E. Hunt 5/28/1925DC1925 322 Allen Charlena Letts Eugene 10/9/1947 DC1948 186 Allen Charles Bronson Blanche 3/31/1953 DC1953 462 Allen Charles Thompson Elnora Root 10/12/1904DC1905 162 Allen Eugene Minnie M. -

Business Finland Neogames Fivr Mixed Reality Report 2017

MIXED REALITY REPORT 2017 BUSINESS FINLAND NEOGAMES FIVR 2 3 BUSINESS FINLAND | NEOGAMES BUSINESS FINLAND | NEOGAMES MIXED REALITY 2017 MIXED REALITY 2017 Content 1. Introduction 1. Introduction 3 lready from the 1990’s there has been a strong will and hope towards a virtual- and augmented reality based gaming experience. For a couple of 2. Terminology of VR, AR, MR and XR 3 decades, the development of technology was quite slow, but after HTC 3. Current Status of the VR/AR field 5 AVive, and the first Oculus consumer version release in March 2016 it seemed that 3.1 Available VR & AR devices and platforms for consumers 6 the technology is finally advanced enough, and the market for B2C VR applications, 3.1.1 High-end tethered VR headsets 6 including games, is ready to open. 3.1.2 Smartphone-based mobile VR headsets 7 The Oculus and Vive releases together with available VC funding and the 3.2 Technological demands in general 7 saturation of the mobile market (resulting in some mobile developers fleeing to 3.3 User expectations 8 VR/AR development) created high hopes towards VR. Basically everything required 4. Future - Towards casual VR 8 was coming together, funding, technology, skills and companies. However, after a 4.1 Four tiers of future VR devices 9 good start and excessive hype the VR games’ B2C market didn’t develop as expected. 4.2 High-end consumer VR devices 10 One clear indicator of that was that some existing VR studios have closed and even 5. AR Devices 10 Icelandic CCP, a big advocate of VR games since 2013, announced in the end of 6. -

Carlson V Summary Minus Report D

8/31/2009 STATE OF ALASKA Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission Carlson Summary Only those with a Negative Balance as of 31 March 2009 Page 1 of 139 Non-Resident Over/Under Balance Fee Differential Interest as of Name Paid Allowance Amount 31Mar2009 Obs —————————————————————————————— —————————————— —————————————— —————————————— —————————————— 1 AABERG, RACHEL M. $355.00 $-110.00 $-87.49 $-197.49 2 AADSEN, KENNETH $480.00 $-713.09 $-4,954.05 $-5,667.14 3 AADSEN, VALERIE S. $3,750.00 $-24.78 $-553.53 $-578.31 4 AAKER, KRIS L. $2,310.00 $10.83 $-1,594.05 $-1,583.22 5 ABAD, JOSE L. $150.00 $-115.97 $-974.02 $-1,089.99 6 ABALAMA, VERA E. $297.00 $-341.76 $-226.50 $-568.26 7 ABART, LEONARD L. (ESTATE) $1,200.00 $-916.84 $-6,935.25 $-7,852.09 8 ABBOTT, STEVE $150.00 $-143.39 $-1,091.22 $-1,234.61 9 ABE, YASUO $540.00 $-213.72 $-1,343.55 $-1,557.27 10 ABELLA, DAREN M. $5,755.00 $311.28 $-5,043.11 $-4,731.83 11 ABERNATHY, STEVEN L. $1,410.00 $-721.26 $-2,914.79 $-3,636.05 12 ABFALTER, BEATRICE $2,100.00 $-77.42 $-961.33 $-1,038.75 13 ABFALTER, FRANCIS K. $240.00 $-232.55 $-2,037.60 $-2,270.15 14 ABFALTER, WILLIAM F. $1,710.00 $-548.66 $-1,151.06 $-1,699.72 15 ABRAMSON, MARKUS W. $1,615.00 $-1,446.22 $-7,296.06 $-8,742.28 16 ACKARET, JOHN $240.00 $-300.79 $-1,744.89 $-2,045.68 17 ACKER, N.MICHAEL $150.00 $-149.66 $-751.56 $-901.22 18 ACKERMAN, JIMMIE G. -

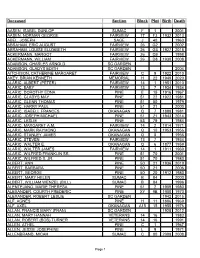

Deceased Section Block Plot Birth Death AASEN, ISABEL DUNLOP SUMAC F 1 2001 AASEN, NORMAN GEORGE FAIRVIEW 17 F3 1932 2013 ABEL

Deceased Section Block Plot Birth Death AASEN, ISABEL DUNLOP SUMAC F 1 2001 AASEN, NORMAN GEORGE FAIRVIEW 17 F3 1932 2013 ABEL, JOSEPH SAGE J 40 1963 ABRAHAM, ERIC AUGUST FAIRVIEW 26 G2 2002 ABRAHAM, LOUISE ELIZABETH FAIRVIEW 26 G3 1927 2018 ACKERMANN, MARGOT FAIRVIEW 26 D9 1998 ACKERMANN, WILLIAM FAIRVIEW 26 D8 1930 2008 ADAMSON, CHARLES ARNOLD SC GARDEN ADAMSON, GLADYS EDITH SC GARDEN 2004 AITCHISON, CATHERINE MARGARET FAIRVIEW C 9 1922 2010 AKEY, BRIAN KENNETH MEMORIAL H 22 1949 2020 ALARIC, ALBERT (PETER) FAIRVIEW 14 1 1951 2010 ALARIC, BABY FAIRVIEW 13 7 1934 1934 ALARIC, DOROTHY EDNA PINE E 15 1916 1967 ALARIC, GLADYS MAY PINE 51 22 1922 1981 ALARIC, GLENN THOMAS PINE 51 80 1979 ALARIC, HARRY PAUL PINE 51 21 2000 ALARIC, ISABELL FRANCES OKANAGAN Q 7 1888 1981 ALARIC, JOSEPH MICHAEL PINE 51 21 1943 2014 ALARIC, LESLIE PINE 53 79 1984 ALARIC, MARGARET A.M. FAIRVIEW 14 2 1914 1971 ALARIC, MARK RAYMOND OKANAGAN Q 10 1953 1956 ALARIC, STANLEY JAMES OKANAGAN Q 8 1956 ALARIC, STEVEN FAIRVIEW 13 7 1934 ALARIC, WALTER E. OKANAGAN Q 6 1877 1959 ALARIC, WALTER JAMES FAIRVIEW 14 1 1911 1969 ALARIC, WILFRED FRANKLIN SR. PINE 51 70 2001 ALARIC, WILFRED X. JR. PINE 51 70 1980 ALBERT, ANN PINE 50 21 1936 2019 ALBERT, BARBARA PINE 50 21 2006 ALBERT, GEORGE PINE 50 20 1912 1980 ALBERT, MARY HELEN SUMAC B 84 2000 ALBERT, WILLIAM WENZEL (BILL) SUMAC B 84 1996 ALENTEJANO, MARIE THERESA PINE 51 2 1909 1980 ALEXANDER, COURTH FREDERIC PINE XY 9B 1900 1970 ALEXANDER, ROBERT LESLIE SC GARDEN 1942 2015 ALF, AGNES PINE H 11 1886 1969 ALF, AXEL OKANAGAN A15