Toward Transformative Learning During Short-Term International Study Tours: Implications for Instructional Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Around the Sea of Galilee (5) the Mystery of Bethsaida

136 The Testimony, April 2003 to shake at the presence of the Lord. Ezekiel that I am the LORD” (v. 23). May this time soon concludes by saying: “Thus will I magnify My- come when the earth will be filled with the self, and sanctify Myself; and I will be known in knowledge of the glory of the Lord and when all the eyes of many nations, and they shall know nations go to worship the King in Jerusalem. Around the Sea of Galilee 5. The mystery of Bethsaida Tony Benson FTER CAPERNAUM, Bethsaida is men- according to Josephus it was built by the tetrarch tioned more times in the Gospels than Philip, son of Herod the Great, and brother of A any other of the towns which lined the Herod Antipas the tetrarch of Galilee. Philip ruled Sea of Galilee. Yet there are difficulties involved. territories known as Iturea and Trachonitis (Lk. From secular history it is known that in New 3:1). Testament times there was a city called Bethsaida Luke’s account of the feeding of the five thou- Julias on the north side of the Sea of Galilee, but sand begins: “And he [Jesus] took them [the apos- is this the Bethsaida of the Gospels? Some of the tles], and went aside privately into a desert place references to Bethsaida seem to refer to a town belonging to the city called Bethsaida” (9:10). on the west side of the lake. A tel called et-Tell 1 The twelve disciples had just come back from is currently being excavated over a mile north of their preaching mission and Jesus wanted to the Sea of Galilee, and is claimed to be the site of be able to have a quiet talk with them. -

Jesus Teaches and Heals

January 31, 2021 4th Sunday in Ordinary Time Jesus Teaches and Heals In this Sunday’s Gospel, Jesus heals a man whom others reject. Through this miracle, Jesus also teaches a powerful lesson about God’s love. What can you tell others about the healing power of the Holy Spirit? Complete the project, and then share how you teach others about Jesus. In the blank space, create a sticker that teaches about something important to you. Examples: taking care of the earth and its creatures, respect for life, being a good friend, choosing joy. You may draw a symbol or share a quote or a verse from the Bible—whatever best expresses your important teaching. Take a picture of your sticker and post it. PFLAUM GOSPEL WEEKLIES Faith Formation Program driver told all the Black riders to stand up so the white riders could sit. While other Black passengers gave up their seats for white riders, Claudette refused. The bus driver drove straight into town and called a The policeman to board the bus and arrest her. Women The police took her, kicking and screaming, Who and kept her in jail until her pastor bailed her out. Later Claudette was found Who started the famous guilty of breaking the Montgomery, Alabama, STOPPED segregation law and placed bus boycott? Was it Rosa the on probation. Parks, who refused to give her seat to a white bus rider? Dr. Mary Fair Burks, chair Buses of the English department Was it the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., who preached at Alabama State College every night to the boycotters? Or and founder of the WPC, was was it women whose names no members repeated the news to disgusted and angry. -

ISRAEL: Faith, Friction and firm Foundations

>> This is the January 2015 issue containing the February Bible Study Lessons BETHLEHEM: Not so little town of great challenges 30 baptiststoday.org ISRAEL: Faith, friction and firm foundations SEE ROCK CITIES: Indeed, these stones can talk 5 WHERE WAS JESUS? Historical evidence vs. holy hype 28 NARRATIVES: Voices from both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian divide 34 MODERN ISRAEL: Politics, peoples and prophesies 36 PILGRIMAGE: Images and reflections from Israel and the West Bank 38 FA TH™ BIBLE STUDIES for adults and youth 17 John D. Pierce Executive Editor [email protected] Julie Steele Chief Operations Officer [email protected] Jackie B. Riley Managing Editor [email protected] PILGRIMAGE: Tony W. Cartledge Contributing Editor IMAGES AND [email protected] REFLECTIONS Bruce T. Gourley Online Editor FROM ISRAEL [email protected] AND THE WEST David Cassady Church Resources Editor BANK [email protected] Terri Byrd Contributing Writer Vickie Frayne Art Director 38 Jannie Lister Customer Service Manager [email protected] Kimberly L. Hovis PERSPECTIVES Marketing Associate [email protected] For good or bad: the witnessing dilemma 9 Gifts to Baptists Today Lex Horton John Pierce Nurturing Faith Resources Manager [email protected] Remembering Isaac Backus and the IN HONOR OF Walker Knight, Publisher Emeritus importance of religious liberty 16 BETTIE CHITTY CHAPPELL Jack U. Harwell, Editor Emeritus Leroy Seat From Catherine Chitty DIRECTORS EMERITI Thomas E. Boland IN HONOR OF R. Kirby Godsey IN THE NEWS Mary Etta Sanders CHARLES AND TONI Nearly one-fourth of American families Winnie V. Williams CLEVENGER turn to church food pantries 10 BOARD OF DIRECTORS From Barry and Amanda Howard Donald L. -

Simon Peter Sample

Contents Introduction .........................................9 1. The Call of the Fisherman ..........................13 2. Walking with Jesus in the Storms ....................41 3. Bedrock or Stumbling Block?........................59 4. “I Will Not Deny You” ..............................89 5. From Cowardice to Courage........................109 6. The Rest of the Story..............................127 Epilogue: The Silent Years ...........................163 Notes .............................................171 Acknowledgments ..................................173 9781501845987_INT_BookLayout.indd 7 10/18/18 12:00 PM 1 The Call of the Fisherman One day Jesus was standing beside Lake Gen- nesaret when the crowd pressed in around him to hear God’s word. Jesus saw two boats sitting by the lake. The fishermen had gone ashore and were washing their nets. Jesus boarded one of the boats, the one that belonged to Simon, then asked him to row out a little distance from the shore. Jesus sat down and taught the crowds from the boat. When he finished speaking to the crowds, he said to Simon, “Row out farther, into the deep water, and drop your nets for a catch.” Simon replied, “Master, we’ve worked hard all night and caught nothing. But because you say so, I’ll drop the nets.” 13 9781501845987_INT_BookLayout.indd 13 10/18/18 12:00 PM SIMON PETER So they dropped the nets and their catch was so huge that their nets were splitting. They signaled for their partners in the other boat to come and help them. They filled both boats so full that they were about to sink. When Simon Peter saw the catch, he fell at Jesus’ knees and said, “Leave me, Lord, for I’m a sinner!” Peter and those with him were overcome with amazement because of the number of fish they caught. -

Foxe's Book of Martyrs

FOXE'S BOOK OF MARTYRS CHAPTER I - History of Christian Martyrs to the First General Persecutions Under Nero Christ our Savior, in the Gospel of St. Matthew, hearing the confession of Simon Peter, who, first of all other, openly acknowledged Him to be the Son of God, and perceiving the secret hand of His Father therein, called him (alluding to his name) a rock, upon which rock He would build His Church so strong that the gates of hell should not prevail against it. In which words three things are to be noted: First, that Christ will have a Church in this world. Secondly, that the same Church should mightily be impugned, not only by the world, but also by the uttermost strength and powers of all hell. And, thirdly, that the same Church, notwithstanding the uttermost of the devil and all his malice, should continue. Which prophecy of Christ we see wonderfully to be verified, insomuch that the whole course of the Church to this day may seem nothing else but a verifying of the said prophecy. First, that Christ hath set up a Church, needeth no declaration. Secondly, what force of princes, kings, monarchs, governors, and rulers of this world, with their subjects, publicly and privately, with all their strength and cunning, have bent themselves against this Church! And, thirdly, how the said Church, all this notwithstanding, hath yet endured and holden its own! What storms and tempests it hath overpast, wondrous it is to behold: for the more evident declaration whereof, I have addressed this present history, to the end, first, that the wonderful works of God in His Church might appear to His glory; also that, the continuance and proceedings of the Church, from time to time, being set forth, more knowledge and experience may redound thereby, to the profit of the reader and edification of Christian faith. -

BETHSAIDA in Hebrew Means “House of Fishermen”

BETHSAIDA in Hebrew means “House of fishermen” Location and Description Long ago, Bethsaida was thought to be located near the present day shore of the Sea of Galilee; however, not all biblical archae- ologists believed that to be true. In 1987, Dr. Rami Arav, an Israeli archaeologist, spent ten days examining what he thought was the real location. He found a large mound called et-Tell, about 1.5 miles north of the Lake. His intense investigation of the site since then has revealed that et-Tell is most likely the ancient site of Bethsaida. Sea of Galilee near Bethsaida There are several possible reasons for the ab- normal distance between the site being excavated as Bethsaida and the location of the Sea of Galilee today. The water level could have dropped because of irrigation or population usage. The delta might have been filled in by sediment over the centuries, or there might have been an earthquake or tec- tonic rift that lifted the city above the Sea. Excavations on the newer site are still underway and several archaeologists have joined together in the Consortium of the Bethsaida Excavations Project, which is part of the department of Interna- tional Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha to work on this project. Old Testament The site of Bethsaida at et-Tell was founded in the tenth century BCE. This area was the capital of the Kingdom of Geshur, whose dynasties ruled for generations. King David of Israel married a daughter of the King of Geshur, named Ma’acha. She bore David a son, Absalom, who at one time found refuge in the Land of Geshur (II Sam. -

Your Healing June 2018

Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture references are from The New King James Version, Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1982. All rights reserved A Publication of: Kingdom Expansion Ministries International 1501 Partin Dr. N. Apt 251 Niceville, FL 32578 USA For Orders Contact: Kevin Martin [email protected] Telephone 1 850 279-3489 Copyright 2018, Kingdom Expansion Ministries International, Inc. Printed in USA ii CONTENTS Preface…….……………........................................................................................................ iv Your Healing is Fully Paid For............................................................................................... 1 Importance of the Blood…................................................................................................. 2 Salvation Includes Healing................................................................................................. 4 Jesus Links Forgiveness of Sin With Healing of Bodies…..….………………………… 6 Sozo Salvation……………………………………………….………………………….. 8 Study Assignment 1……………………………………………………………………... 9 Healing is God’s Will……………......................................................................................... 11 How We Know Healing Is His Will……………………………………………………… 13 The Prayer of Faith………………………………………………………………………. 16 Study Assignment 2……………………………………………………………………… 18 Authority to Heal………........................................................................................................ 19 Condemnation Separates You From God......................................................................... -

Sessions 5 and 6: Important Touchpoints in Jesus' Life • This

Sessions 5 and 6: Important touchpoints in Jesus’ life • This week we continue to explore introductory and background issues related to the four Gospels, beginning with information about Capernaum, Jesus Galilean headquarters. • Capernaum, the home of some of Jesus’ disciples, served as the Lord’s headquarters during a sizable portion of His public ministry. It was a fishing village built on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee. • Capernaum hosted a Roman garrison that maintained peace in the region. Major highways crisscrossed at Capernaum, making it militarily strategic. • Because of its fishing and trading industries, the city was something of a melting pot of Greek, Roman, and Jewish cultures. • Visitors to the site today can see the remains of an early Christian church believed to have been constructed on the site of Peter’s home. • We next consider the Sea of Galilee. This body of water is located in what was northern Palestine during the first century. • The Sea of Galilee was known by at least three other names: the Sea of Kinnereth (Josh. 11:2), the Lake of Gennesaret (Luke 5:1), and the Sea of Tiberias (John 6:1). • At its farthest distances, the lake is 13 miles long and 7.5 miles wide. In places it reaches a depth of 160 feet. The lowness of the lake surface, 685 feet below sea level, contributes to the almost tropical character of the weather. • The lake’s setting is beautiful. The lake itself abounds with freshwater fish. • Beyond the shoreline of pebbles and shells, wildflowers grow. High green hills ring most of the lake, and the surrounding land is exceptionally fertile for growing crops. -

Jason Piland – “Mark 8:22-26: Jesus the Parable Worker”

Mark 8:22–26: Jesus the Parable-Worker or The Healing of the Blind Man at Bethsaida as a Parable of the Disciples’ Faith Jason Piland NT 508: Gospels, Dr. Kruger Reformed Theological Seminary, Charlotte December 8, 2016 I. Introduction Upon an initial reading, there is something quite striking about the account of Jesus healing the blind man at Bethsaida in Mark 8:22–26. A cursory glance reveals that Jesus healed the blind man in two phases, almost as if he was not able to heal him on the first attempt. No doubt this passage has left many Christian Bible readers puzzled, wondering why Jesus did not heal the man all at once, as was his custom. The pericope reads, according to the ESV, in full: 22 And they came to Bethsaida. And some people brought to him a blind man and begged him to touch him. 23 And he took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the village, and when he had spit on his eyes and laid his hands on him, he asked him, “Do you see anything?” 24 And he looked up and said, “I see people, but they look like trees, walking.” 25 Then Jesus laid his hands on his eyes again; and he opened his eyes, his sight was restored, and he saw everything clearly. 26 And he sent him to his home, saying, “Do not even enter the village.” The questions surrounding the two-staged healing are legion: Why did Jesus do it this way? What was the physical state of the man’s eyes “between” the healings? Did the disciples think there was anything unusual about Jesus acting this way? Why did Jesus tell the man not to go to the village when presumably that is where he lived? It could even be asked if Jesus was able to heal the man in one stage. -

Has Bethsaida-Julias Been Found?

Has Bethsaida-Julias Been Found? Mordechai Aviam and R. Steven Notley In the nineteenth century, European and American explorers visited the Holy Land in exerted attempts to identify historical sites (biblical and extra-biblical), whose locations had long been forgotten. Many of these cities, towns and villages were destroyed or abandoned, and the only traces of their existence are to be found in passing references in the ancient historical records. The task to identify these lost sites requires a complex application of multiple disciplines, including history, toponomy, topography, and archaeology (Rainey and Notley 2006:9-24; Rainey 1984:8-11). Absent actual inscriptional evidence, archaeology serves as the best means to confirm whether the material remains from a site correspond to the physical descriptions and events (e.g. settlement, destruction, etc.) found in the historical records. Of course, archaeological data was not available to these early explorers until the beginning of the twentieth century. So, it should come as no surprise that some of the earlier suggested site identifications were later found to be mistaken. One of the lost places that interested the early explorers was a small Jewish fishing village called Bethsaida, first mentioned in the New Testament. Edward Robinson proposed its location at et-Tell on a hill overlooking the Sea of Galilee (Robinson and Smith 1867:2:413-14). Gottlieb Schumacher countered that et-Tell’s significant distance from the lake prevented it from being a fishing village. Instead, he proposed el-Araj, which was situated on the lakeshore, as the preferred location for Bethsaida (Schumacher 1888:93). -

Pioneering in Modern City Missions

PIONEERING IN MODERN CITY MISSIONS By r^i.^iAR JAMES HELMS z Q 3 03 < O z o to as O Q O o <-J o z METHODIST OS CENTER O BY1616.3 H481P ^ p \ ^^ s 5lon_onJ4Rc+^lv'e5 ^nice D mec+^ODl SC C4AVV- Presented by i^ JBOSi, " ^oiiirj;^ Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2011 witli funding from Drew University witli a grant from the American Theological Library Association http://www.archive.org/details/pioneeringinmode01helm REV. HENRY MORGAN 1825— 1884 Founder of Morgan Chapel. PIONEERING IN MODERN CITY MISSIONS BY EDGAR JAMES HELMS WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY BISHOP FREDERICK B. FISHER OF CALCUTTA. INDIA. BOSTON. MASS. MORGAN MEMORIAL PRINTING DEPARTMENT 1927 B tS=;agacggg=3)-Jy:4j:-a-j)-j)-4V-g^^ A»e THCDIST ^:tea=lfcar^^^^t^^Q^^r:tt-tt-^r<t^^<^^t^^ ain iMg Mifr . THE LITTLE MOTHER WHO HAS UNCOMPLAININGLY CARRIED ON THE MOST IMPORTANT AND MOST DIFFICULT AND DELIGHTFUL TASK IN THE WORLD — THE CARE OF A BIG FAMILY OF GIRLS AND BOYS. Page Seven PAGE PREFACE 13 INTRODUCTION BY BISHOP FREDERICK B. FISHER .... 15 PREPARATION AND PRE-PREPARATION 17 II. THE REVOLT OF YOUTH 21 III. MEETING YOUTH'S REVOLT 25 IV. TWELVE YEARS OF STRUGGLE 29 V. GETTING INTO CITY MISSIONARY V/ORK 33 VI. A UNIQUE MISSION 39 VII. RESCUING THE LOST 43 (FRED H. SEAVEY SEMINARY SETTLEMENT) VIII. THE CHILDREN'S SETTLEMENT 49 IX. A COUNTRY PLANTATION 57 X. THE CHURCH OF ALL NATIONS 65 XI. THE GOODWILL INDUSTRIES 69 XII. ELIZA A. HENRY WORKING WOMEN'S SETTLEMENT 77 THE COMFORTS OF HOME 81 GOODWILL INDUSTRIES AROUND THE WORLD 87 A SUMMARY OF ACHIEVEMENT 99 APPENDIX 103 >:^=!^=?>=?>=>=>=r>!fr>rr>—^—>—"(—>—I—"*—J—>^»!^ Page Nine \'rsct=ifc=tt=g=ir-<^-f^'<^'ir-trt^-fr-ff-<^^^ ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE HENRY MORGAN 4 STAGES THROUGH THE SEAVEY 42 SHERIFF FRED H. -

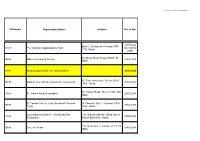

Organisation Name Address the Voluntary Organisations Fund Block

Commissioner for Voluntary Organisations VO Number Organisation Name Address Date of App. 03/07/2009 Block C, Beltissebh, Floriana, FRN 001/09 The Voluntary Organisations Fund (Act XXII of 1700, Malta 2007) 21, Mosta Road, Naxxar NXR1154 - 002/08 Maltese Mentoring Society 22/02/2008 Malta 003/08 Assocjazzjoni Kunsilli ta' l-Iskejjel (AKS) 22/02/2008 65, Triq l-Annunzjata, Sliema, SLM 004/08 Marana Tha' Catholic Charismatic Community 25/02/2008 1465 - Malta 51, Tarxien Road, Tarxien TXN 1090, 005/08 St. Jeanne Antide Foundation 26/02/2008 Malta St. Edward College (Lady Strickland Charitable St. Edward's Street, Vittoriosa, BRG 006/08 29/02/2008 Trust) 9039 - Malta Good Shepherd Sisters - Dar Merhba Bik 130, "Dar Merhba Bik", Birbal Street, 007/08 03/03/2008 Foundation Balzan BZN 9014 - Malta 133, Melita Street, Valletta, VLT 1123 - 008/08 Din L-Art Helwa 03/03/2008 Malta Commissioner for Voluntary Organisations 16, Misrah Dicembru Tlettax, Zejtun 009/08 Paulo Freire Institute Foundation 07/03/2008 ZTN 1021 - Malta 7, Saint Adeotato Lane, Zejtun, ZTN 010/08 Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice Foundation 07/03/2008 3072, Malta 61, Saint Lazarus Street, Cospicua 011/08 Centru Tbexbix 14/03/2008 BML 1140 - Malta Orange Grove, Block B, Birbal Street, 012/08 Malta Institute of Management 17/03/2008 Balzan BZN 9013 - Malta YWCA (MALTA) - Young Women's Christian Centru Nazzjonali, 178 Valley Road, 013/08 20/03/2008 Association Msida MSD 9029 - Malta c/o 35, Censu Bugeja Street, Hamrun 014/08 Grupp Missjunarju Kull Bniedem Hija 20/03/2008 HMR 1057 - Malta Eureeka Court, Block A Flat 6, Main 015/08 Mission Fund 28/03/2008 Road, Mosta MST 1018 – Malta 016/08 Socjeta' Filarmonika Lourdes AD 1977 01/04/2008 424, St.