Has Akira Always Been a Cyberpunk Comic?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB issue 27: November -December 2001 FILM FESTIVAL OF CATALUNYA AT SITGES Fresh from Japan: Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin The International Film Festival of Catalunya (October 4 - 13) held at Sitges - the charming seaside village just south of Barcelona, infused with life from the international gay community - this year again presented a mix of mainstream and fantastic film. (The festival's original title was Festival of Fantastic Cinema.) The more mainstream section (called Gran Angular ) showed 12 films only as opposed to the large offering of 27 films in the Fantastic section, evidence that this genre still predominates even though it is no longer exclusive. Japan made a big showing this year in both categories. Two feature-length animated films caught the attention of Sara Martin , an English literature teacher at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and anime fan, who reports here on the latest offerings by two of Japan's most outstanding anime film makers, and gives us both a wee history and future glimpse of the anime genre - it's sure not kids' stuff and it's not always pretty. Japanese animated feature films are known as anime. This should not be confused with manga , the name given to the popular printed comics on which anime films are often based. Western spectators raised in a culture that identifies animation with cartoon films and TV series made predominately for children, may be surprised to learn that animation enjoys a far higher regard in Japan. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

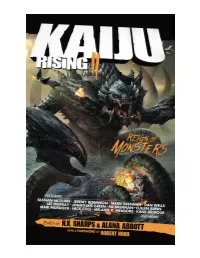

Kaiju-Rising-II-Reign-Of-Monsters Preview.Pdf

KAIJU RISING II: Reign of Monsters Outland Entertainment | www.outlandentertainment.com Founder/Creative Director: Jeremy D. Mohler Editor-in-Chief: Alana Joli Abbott Publisher: Melanie R. Meadors Senior Editor: Gwendolyn Nix “Te Ghost in the Machine” © 2018 Jonathan Green “Winter Moon and the Sun Bringer” © 2018 Kane Gilmour “Rancho Nido” © 2018 Guadalupe Garcia McCall “Te Dive” © 2018 Mari Murdock “What Everyone Knows” © 2018 Seanan McGuire “Te Kaiju Counters” © 2018 ML Brennan “Formula 287-f” © 2018 Dan Wells “Titans and Heroes” © 2018 Nick Cole “Te Hunt, Concluded” © 2018 Cullen Bunn “Te Devil in the Details” © 2018 Sabrina Vourvoulias “Morituri” © 2018 Melanie R. Meadors “Maui’s Hook” © 2018 Lee Murray “Soledad” © 2018 Steve Diamond “When a Kaiju Falls in Love” © 2018 Zin E. Rocklyn “ROGUE 57: Home Sweet Home” © 2018 Jeremy Robinson “Te Genius Prize” © 2018 Marie Brennan Te characters and events portrayed in this book are fctitious or fctitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors unless otherwise specifed. Tis book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Published by Outland Entertainment 5601 NW 25th Street Topeka KS, 66618 Paperback: 978-1-947659-30-8 EPUB: 978-1-947659-31-5 MOBI: 978-1-947659-32-2 PDF-Merchant: 978-1-947659-33-9 Worldwide Rights Created in the United States of America Editor: N.X. Sharps & Alana Abbott Cover Illustration: Tan Ho Sim Interior Illustrations: Frankie B. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira Shannon Victoria Stevens University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Repository Citation Stevens, Shannon Victoria, "The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 371. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1606942 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RHETORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF GOJIRA by Shannon Victoria Stevens Bachelor of Arts Moravian College and Theological Seminary 1993 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication Studies Department of Communication Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2010 Copyright by Shannon Victoria Stevens 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Shannon Victoria Stevens entitled The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies David Henry, Committee Chair Tara Emmers-Sommer, Committee Co-chair Donovan Conley, Committee Member David Schmoeller, Graduate Faculty Representative Ronald Smith, Ph. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Katsuhiro Otomo Grand Prix D’Angoulême 2015

KATSUHIRO OTOMO Grand Prix d’ANGOULÊME 2015 En choisissant d’attribuer le Grand Prix de la 42e édition du Festival international de la bande dessinée à Katsuhiro Otomo, la communauté des auteur(e)s qui a exprimé ses suffrages lors des deux tours du vote organisé par voie électronique en décembre 2014 puis janvier 2015 a accompli un geste historique. C’est la première fois en effet que cette récompense, la plus prestigieuse du palmarès du Festival, est attribuée à un auteur japonais, soulignant ainsi la place prise par le manga dans l’histoire du 9e art. Katsuhiro Otomo couronné, c’est le meilleur du manga qui se voit ainsi légitimement célébré en Europe. Né au Japon en 1954, Katsuhiro Otomo se met à dessiner professionnellement très tôt, au sortir de l’adolescence, et signe dès les années 70 ses premiers récits courts, souvent d’inspiration SF ou fantastique. Ainsi Domu - Rêves d’enfant (1981), traduit bien plus tard en langue française, qui se signale déjà par une maîtrise narrative, des innovations formelles et une science du cadrage remarquables chez un si jeune auteur. Le travail d’Otomo, d’emblée, exprime son goût de toujours pour le cinéma, qu’il aura par la suite de multiples occasions de satisfaire en devenant également cinéaste. Mais c’est à partir de 1982, alors que le jeune mangaka a déjà derrière lui près d’une décennie d’expérience, que le phénomène Otomo se déploie véritablement. Dans les pages du magazine Young, alors qu’il n’a que 28 ans, il entreprend un long récit post-apocalyptique d’une intensité et d’une ampleur visionnaire saisissantes : Akira. -

Bornoftrauma.Pdf

Born of Trauma: Akira and Capitalist Modes of Destruction Thomas Lamarre Images of atomic destruction and nuclear apocalypse abound in popular culture, familiar mushroom clouds that leave in their wake the whole- sale destruction of cities, towns, and lands. Mass culture seems to thrive on repeating the threat of world annihilation, and the scope of destruction seems continually to escalate: planets, even solar systems, disintegrate in the blink of an eye; entire populations vanish. We confront in such images a compulsion to repeat what terrifies us, but repetition of the terror of world annihilation also numbs us to it, and larger doses of destruction become necessary: increases in magnitude and intensity, in the scale and the quality of destruction and its imaging. Ultimately, the repetition and escalation promise to inure us to mass destruction, producing a desire to get ever closer to it and at the same time making anything less positions 16:1 doi 10.1215/10679847-2007-014 Copyright 2008 by Duke University Press positions 16:1 Spring 2008 132 than mass destruction feel a relief, a “victory.” Images of global annihilation imply a mixture of habituation, fascination, and addiction. Trauma, and in particular psychoanalytic questions about traumatic rep- etition, provides a way to grapple with these different dimensions of our engagement with images of large-scale destruction. Dominick LaCapra, for instance, returns to Freud’s discussion of “working-through” (mourning) and “acting out” (melancholia) to think about different ways of repeating trauma. “In acting-out,” he writes, “one has a mimetic relation to the past which is regenerated or relived as if it were fully present rather than repre- sented in memory and inscription.”1 In other words, we repeat the traumatic event without any sense of historical or critical distance from it, precisely because the event remains incomprehensible. -

The Terminator by John Wills

The Terminator By John Wills “The Terminator” is a cult time-travel story pitting hu- mans against machines. Authored and directed by James Cameron, the movie features Arnold Schwarzenegger, Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn in leading roles. It launched Cameron as a major film di- rector, and, along with “Conan the Barbarian” (1982), established Schwarzenegger as a box office star. James Cameron directed his first movie “Xenogenesis” in 1978. A 12-minute long, $20,000 picture, “Xenogenesis” depicted a young man and woman trapped in a spaceship dominated by power- ful and hostile robots. It introduced what would be- come enduring Cameron themes: space exploration, machine sentience and epic scale. In the early 1980s, Cameron worked with Roger Corman on a number of film projects, assisting with special effects and the design of sets, before directing “Piranha II” (1981) as his debut feature. Cameron then turned to writing a science fiction movie script based around a cyborg from 2029AD travelling through time to con- Artwork from the cover of the film’s DVD release by MGM temporary Los Angeles to kill a waitress whose as Home Entertainment. The Library of Congress Collection. yet unborn son is destined to lead a resistance movement against a future cyborg army. With the input of friend Bill Wisher along with producer Gale weeks. However, critical reception hinted at longer- Anne Hurd (Hurd and Cameron had both worked for lasting appeal. “Variety” enthused over the picture: Roger Corman), Cameron finished a draft script in “a blazing, cinematic comic book, full of virtuoso May 1982. After some trouble finding industry back- moviemaking, terrific momentum, solid performances ers, Orion agreed to distribute the picture with and a compelling story.” Janet Maslin for the “New Hemdale Pictures financing it. -

What Is Anime?

1 Fall 2013 565:333 Anime: Introduction to Japanese Animation M 5: 3:55pm-5:15pm (RAB-204) W 2, 3: 10:55am-1:55pm (RAB-206) Instructor: Satoru Saito Office: Scott Hall, Room 338 Office Hours: M 11:30am-1:30pm E-mail: [email protected] Course Description This course examines anime or Japanese animation as a distinctly Japanese media form that began its development in the immediate postwar period and reached maturity in the 1980s. Although some precedents will be discussed, the course’s primary emphasis is the examination of the major examples of Japanese animation from 1980s onward. To do so, we will approach this media form through two broad frameworks. First, we will consider anime from the position of media studies, considering its unique formal characteristics. Second, we will consider anime within the historical and cultural context of postwar and contemporary Japan by tracing its specific themes and characteristics, both on the level of content and consumption. The course will be taught in English, and there are no prerequisites for this course. To allow for screenings of films, one of two class meetings (Wednesdays) will be a double- period, which will combine screenings with introductory lectures. The other meeting (Mondays), by which students should have completed all the reading assignments of the week, will provide post-screening lectures and class discussions. Requirements Weekly questions, class attendance and performance 10% Four short papers (3 pages each) 40% Test 15% Final paper (8-10 pages double-spaced) 35% Weekly questions, class attendance and performance Students are expected to attend all classes and participate in class discussions. -

Read Book the Ghost in the Shell Deluxe Complete Box

THE GHOST IN THE SHELL DELUXE COMPLETE BOX SET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Shirow Masamune | 864 pages | 06 Feb 2020 | Kodansha America, Inc | 9781632366429 | English | New York, United States The Ghost In The Shell Deluxe Complete Box Set PDF Book Haha…okay as sad as this is…. Similar threads. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. And that is saying something. Greg rated it it was amazing Dec 23, Trailer TV Spots Textless opening. This is the first English-language Shirow series that will be produced in the authentic right-to- left reading format, as originally published in Japan. Hardcover, 9-in. Jungle Cruise You are commenting using your Facebook account. Now he has only his job and his beloved Basset hound, Gabriel. The only biological component left is her brain. There's just one catch: it's back-ordered and will ship in one to three months. Ghost in the Shell 7 books. Blu-ray Night Watch. Most books of this nature are mostly art with a bit of text, but this one saves its gallery and production sketches for the last 36 pages. Anime a. Interview with art director Yusuke Takeda and conceptual artist Hiroshi Kato Kodansha International. This third volume however… The focus was truly there. You can have light and frothy Tachikoma silliness, and that you have the utter bleakness of something like Jungle Cruise. Candice Snow rated it it was amazing Dec 01, With that being said, I still see the light at the end of this tunnel with the chance to finally check out the anime adaptations that have clearly been the source of all the praise garnered for The Ghost in the Shell name. -

Monster Musume, Vol. 10 Story & Art by OKAYADO

Seven Seas December 2016 Masamune-kun’s Revenge, vol. 3 Story by Takeoka Hazuki Art by Tiv A deliciously funny revenge tale for fans of Skip Beat and Toradora! Masamune-kun’s Revenge is an ongoing romantic comedy about a young man seeking vengence against his greatest bully by confronting her years after a complete physical and social transformation. This tale of vanity, vegeance, and rediscovery is full of comedy and heart, along with great artwork that will appeal to fans of series such as Haganai: I Don’t Have Many Friends and Toradora!. Masamune-kun’s Revenge will be published by Seven Seas as single volumes, each containing a full-color insert. s an overweight child, Makabe Masamune was mercilessly Ateased and bullied by one particular girl, Adagaki Aki. (cover not final) Determined to one day exact his revenge upon her, Makabe begins a rigorous regimen of self-improvement and personal transformation. MANGA Trade Paperback Years later, Masamune reemerges as a new man. Handsome, ISBN: 978-1-626923-66-9 popular, with perfect grades, and good at sports, Masamune- $12.99/US | $14.99/CAN kun transfers to Aki’s school and is unrecognizable to her. Now, 5” x 7.125”/ 180 pages Masamune-kun is ready to confront the girl who bullied him so many Age: Older Teen (16+) years ago and humiliate her at last. Revenge is sweet! On Sale: December 6, 2016 Takeoka Hazuki is a Japanese author best known for Masamune- MARKETING PLANS: • Promotion at gomanga.com kun’s Revenge. • Promotion on Twitter, Tumblr, and Facebook Tiv is a Japanese artist best known for Masamune-kun’s Revenge.