Prehistory and Early History of the Malpai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interpretation of the Structural Geology of the Franklin Mountains, Texas Earl M

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/26 An interpretation of the structural geology of the Franklin Mountains, Texas Earl M. P. Lovejoy, 1975, pp. 261-268 in: Las Cruces Country, Seager, W. R.; Clemons, R. E.; Callender, J. F.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 26th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 376 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1975 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

I GEOSPATIAL SYNTHESIS of GRASSLANDS CONSERVATION

GEOSPATIAL SYNTHESIS OF GRASSLANDS CONSERVATION INFORMATION Final Report – Sept 30, 2016 Prepared for: Desert Landscape Conservation Cooperative c/o Matthew Grabau Science Coordinator Prepared by: Bird Conservancy of the Rockies Maureen D. Correll Allison Shaw Adrián Quero Arvind Panjabi Greg Levandoski Primary Contact: Maureen Correll 14500 Lark Bunting Lane Brighton, Colorado 80603 [email protected] Suggested citation: Correll, M.D., Shaw, A., Quero, A., Panjabi, A.O., and Levandoski, G. 2016. Geospatial synthesis of grasslands conservation information. Final report. Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, Brighton, Colorado, USA. i BIRD CONSERVANCY OF THE ROCKIES Mission: conserving birds and their habitats through science, education and land stewardship Bird Conservancy of the Rockies conserves birds and their habitats through an integrated approach of science, education and land stewardship. Our work radiates from the Rockies to the Great Plains, Mexico and beyond. Our mission is advanced through sound science, achieved through empowering people, realized through stewardship and sustained through partnerships. Together, we are improving native bird populations, the land and the lives of people. Goals 1. Guide conservation action where it is needed most by conducting scientifically rigorous monitoring and research on birds and their habitats within the context of their full annual cycle 2. Inspire conservation action in people by developing relationships through community outreach and science-based, experiential education -

By Douglas P. Klein with Plates by G.A. Abrams and P.L. Hill U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado

U.S DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY STRUCTURE OF THE BASINS AND RANGES, SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO, AN INTERPRETATION OF SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTIONS by Douglas P. Klein with plates by G.A. Abrams and P.L. Hill U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado Open-file Report 95-506 1995 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. The use of trade, product, or firm names in this papers is for descriptive purposes only, and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. STRUCTURE OF THE BASINS AND RANGES, SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO, AN INTERPRETATION OF SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTIONS by Douglas P. Klein CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................. 1 DEEP SEISMIC CRUSTAL STUDIES .................................. 4 SEISMIC REFRACTION DATA ....................................... 7 RELIABILITY OF VELOCITY STRUCTURE ............................. 9 CHARACTER OF THE SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTION ..................... 13 DRILL HOLE DATA ............................................... 16 BASIN DEPOSITS AND BEDROCK STRUCTURE .......................... 20 Line 1 - Playas Valley ................................... 21 Cowboy Rim caldera .................................. 23 Valley floor ........................................ 24 Line 2 - San Luis Valley through the Alamo Hueco Mountains ....................................... 25 San Luis Valley ..................................... 26 San Luis and Whitewater Mountains ................... 26 Southern -

The Malpai Borderlands Group

Collaboration in the Borderlands: The Malpai Borderlands Group Item Type text; Article Authors Allen, Larry S. Citation Allen, L. S. (2006). Collaboration in the borderlands: the Malpai borderlands group. Rangelands, 28(3), 17-21. DOI 10.2111/1551-501X(2006)28[17:CITBTM]2.0.CO;2 Publisher Society for Range Management Journal Rangelands Rights Copyright © Society for Range Management. Download date 29/09/2021 16:36:54 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/639616 Collaboration in the Borderlands: The Malpai Borderlands Group After 10 years of efforts to preserve the open spaces and way of life of the Borderlands Region, the Malpai Borderlands Group is now internationally recognized as an outstanding example of collaborative planning and management of large landscapes. By Larry S. Allen Roots of Change community in New Mexico to join in the discussions, and several points of agreement were discovered. Strongest agreement was in the areas of preservation of open space and As our society is now increasingly polarized on the issues the need to restore fire as a functioning ecological process. It of natural resource use and protection of the environment, was agreed that livestock grazing requires open space and we endeavor to be at the Radical Center. —Bill McDonald that preservation of the ranching industry is important to prevent habitat fragmentation. The Malpai Planning Area includes 2 valleys at an eleva- arly in the 1990s, several neighbors along the tion of about 4,000 feet, which support semidesert grassland Mexican border in Southeastern Arizona and and Chihuahuan desert scrub; 1 higher grassland valley Southwestern New Mexico began to meet period- (about 5,000 feet) with plains grassland; and 2 mountain ically at Warner and Wendy Glenn’s Malpai ranges. -

Runoff and Sediment Yield from Proxy Records: Upper Animas Creek Basin, New Mexico

United States Department of Agriculture Runoff and Sediment Yield from Forest Service Proxy Records: Rocky Mountain Research Station Research Paper RMRS-RP-18 Upper Animas Creek Basin, New Mexico June 1999 W. R. Osterkamp Abstract Osterkamp, W. R. 1999. Runoff and sediment yield from proxy records: upper Animas Creek Basin, New Mexico. Res. Pap. RMRS-RP-18. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 50 p. Analyses of water- and sediment-yield records from the Walnut Gulch Experimental Watershed, the San Simon Wash Basin, and the Jornada Experimental Range, combined with observations of regional variations in climate, geology and soils, vegetation, topography, fire frequency, and land-use history, allow estimates of present conditions of water and sediment discharges in the upper Animas Creek Basin, New Mexico. Further, the records are used to anticipate fluxes of water and sediment should watershed conditions change. Results, intended principally for hydrologists, geomorpholo- gists, and resource managers, suggest that discharges of water and sediment in the upper Animas Creek Basin approximate those of historic, undisturbed conditions, and that erosion rates may be generally lower than those of comparison watersheds. If conversion of grassland to shrubland occurs, sediment yields, due to accelerated upland gully erosion, may increase by 1 to 3 orders of magnitude. However, much of the released sediment would likely be deposited along Animas Creek, never leaving the upper Animas Creek Basin. Keywords: runoff, sediment yield, erosion, Animas Creek Author W. R. Osterkamp is a research hydrologist with the U. S. Geological Survey, Water Resources Division, Tucson, AZ. -

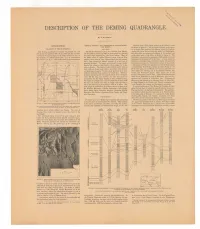

Description of the Deming Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE DEMING QUADRANGLE, By N. H. Darton. INTRODUCTION. GENERAL GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTHWESTERN Paleozoic rocks. The general relations of the Paleozoic rocks NEW MEXICO. are shown in figure 3. 2 All the earlier Paleozoic rocks appear RELATIONS OF THE QUADRANGLE. STRUCTURE. to be absent from northern New Mexico, where the Pennsyl- The Deming quadrangle is bounded by parallels 32° and The Rocky Mountains extend into northern New Mexico, vanian beds lie on the pre-Cambrian rocks, but Mississippian 32° 30' and by meridians 107° 30' and 108° and thus includes but the southern part of the State is characterized by detached and older rocks are extensively developed in the southern and one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's surface, an area, in mountain ridges separated by wide desert bolsons. Many of southwestern parts of the State, as shown in figure 3. The that latitude, of 1,008.69 square miles. It is in southwestern the ridges consist of uplifted Paleozoic strata lying on older Cambrian is represented by sandstone, which appears to extend New Mexico (see fig. 1), a few miles north of the international granites, but in some of them Mesozoic strata also are exposed, throughout the southern half of the State. At some places the and a large amount of volcanic material of several ages is sandstone has yielded Upper Cambrian fossils, and glauconite 109° 108° 107" generally included. The strata are deformed to some extent. in disseminated grains is a characteristic feature in many beds. Some of the ridges are fault blocks; others appear to be due Limestones of Ordovician age outcrop in all the larger ranges solely to flexure. -

Grasslands Ecosystems, Endangered Agriculture Species, and Sustainable Ranching Forest Service in the Mexico-U.S

United States Department of Grasslands Ecosystems, Endangered Agriculture Species, and Sustainable Ranching Forest Service in the Mexico-U.S. Borderlands: Rocky Mountain Research Station Conference Proceedings Proceedings RMRS-P-40 Ecosistemas de Pastizales, Especies en June 2006 Peligro y Ganadería Sostenible en Tierras Fronterizas de México- Estados Unidos: Conferencia Transcripciõnes Basurto, Xavier; Hadley, Diana, eds. 2006. Grasslands ecosystems, endangered species, and sustainable ranching in the Mexico-U.S. borderlands: Conference proceedings. RMRS-P-40. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p. Abstract The semi-arid grasslands in the Mexico-United States border region are relatively intact and provide one of the best opportunities in North America to preserve and nurture an extensive series of grassland ecosystems. The conference was organized to increase appreciation for the importance of the remaining semi-arid grasslands and to create a platform for expanding the integration of natural and social sciences among individuals and organizations. The conference was attended by ranchers, environmentalists, academics, and agency personnel from both nations. Main topics include grassland ecology and biodiversity, management and conservation, and sustainable borderland ranching. Endangered species management, especially of black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus), was an important topic. Oral presentations were in English or Spanish, with simultaneous translations, and the papers have been printed in both languages. The conference revealed the ties between ecological processes and environmental conditions in the Borderland grasslands and the cultural and economic priorities of the human communities who depend on them. This recognition should enable interested people and groups to work together to achieve satisfactory solutions to the challenges of the future. -

Sky Island Grassland Assessment: Identifying and Evaluating Priority Grassland Landscapes for Conservation and Restoration in the Borderlands

Sky Island Grassland Assessment: Identifying and Evaluating Priority Grassland Landscapes for Conservation and Restoration in the Borderlands David Gori, Gitanjali S. Bodner, Karla Sartor, Peter Warren and Steven Bassett September 2012 Animas Valley, New Mexico Photo: TNC Preferred Citation: Gori, D., G. S. Bodner, K. Sartor, P. Warren, and S. Bassett. 2012. Sky Island Grassland Assessment: Identifying and Evaluating Priority Grassland Landscapes for Conservation and Restoration in the Borderlands. Report prepared by The Nature Conservancy in New Mexico and Arizona. 85 p. i Executive Summary Sky Island grasslands of central and southern Arizona, southern New Mexico and northern Mexico form the “grassland seas” that surround small forested mountain ranges in the borderlands. Their unique biogeographical setting and the ecological gradients associated with “Sky Island mountains” add tremendous floral and faunal diversity to these grasslands and the region as a whole. Sky Island grasslands have undergone dramatic vegetation changes over the last 130 years including encroachment by shrubs, loss of perennial grass cover and spread of non-native species. Changes in grassland composition and structure have not occurred uniformly across the region and they are dynamic and ongoing. In 2009, The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) launched its Sky Island Grassland Initiative, a 10-year plan to protect and restore grasslands and embedded wetland and riparian habitats in the Sky Island region. The objective of this assessment is to identify a network of priority grassland landscapes where investment by the Foundation and others will yield the greatest returns in terms of restoring grassland health and recovering target wildlife species across the region. -

Southwest NM Publication List

Southwest New Mexico Publication Inventory Draft Source of Document/Search Purchase Topic Category Keywords County Title Author Date Publication/Journal/Publisher Type of Document Method Price Geology 1 Geology geology, seismic Southwestern NM Six regionally extensive upper-crustal Ackermann, H.D., L.W. 1994 U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 94- Electronic file USGS publication search refraction profiles, seismic refraction profiles in Southwest New Pankratz, D.P. Klein 695 (DJVU) http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/usgspubs/ southwestern New Mexico ofr/ofr94695 Mexico, 2 Geology Geology, Southwestern NM Magmatism and metamorphism at 1.46 Ga in Amato, J.M., A.O. 2008 In New Mexico Geological Society Fall Field Paper in Book http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/g $45.00 magmatism, the Burro Mountains, southwestern New Boullion, and A.E. Conference Guidebook - 59, Geology of the Gila uidebooks/59/ metamorphism, Mexico Sanders Wilderness-Silver City area, 107-116. Burro Mountains, southwestern New Mexico 3 Geology Geology, mineral Catron County Geology and mineral resources of York Anderson, O.J. 1986 New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Electronic file (PDF) NMBGMR search $10.00 for resources, York Ranch SE quadrangle, Cibola and Catron Resources Open File Report 220A, 22 pages. <http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publicatio CD Ranch, Fence Counties, New Mexico ns/openfile/details.cfml?Volume=2 Lake, Catron, 20A> Cibola 4 Geology Geology, Zuni Salt Catron County Geology of the Zuni Salt Lake 7 1/2 Minute Anderson, O.J. 1994 New Mexico Bureau of Mines and -

A Preliminary Assessment of the Geologic Setting, Hydrology, and Geochemistry of the Hueco Tanks Geothermal Area, Texas and New Mexico

Geological Circular 81-1 APreliminaryAssessmentoftheGeologicSetting,Hydrology,andGeochemistyoftheHuecoTanksGeothermalArea,TexasandNewMexico Christopher D.Henry and James K.Gluck jointly published by Bureau of Economic Geology The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712 W. L.Fisher,Director and Texas Energy and Natural Resources Advisory Council Executive Office Building 411 West 13th Street, Suite 800 Austin, Texas 78701 Milton L. Holloway, Executive Director prime funding provided by Texas Energy and Natural Resources Advisory Council throughInteragency Cooperation Contract No.IAC(80-81)-0899 1981 Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Regional geologic setting 2 Origin and locationof geothermal waters 5 Hot wells 5 Source of heat and ground-water flow paths 5 Faults in geothermal area 9 Implications of geophysical data 15 Hydrology 16 Data availability 16 Water-table elevation 17 Substrate permeability 19 Geochemistry 22 Geothermometry 27 Summary 32 Acknowledgments 32 References 33 Appendix A. Well data 35 Appendix B. Chemical analyses Wl Appendix C. Well designations WJ Figures 1. Tectonic map of Hueco Bolson near El Paso, Texas 3 2. Wells in Hueco Tanks geothermal area 6 3. Measured andreported temperatures ( C) of thermal and nonthermal wells 7 4. Depth to bedrock, absolute elevation of bedrock, and inferred normal faults . 10 5. Generalized west-east cross sections in Hueco Tanks geothermal area . .11 6. Depth to water table, absolute elevation of water table, and water- table elevation contours 18 111 7. Percentages of gravel, sand, clay, and bedrock from driller's logs 21 8. Trilinear diagram of thermal and nonthermal waters 24 9. Total dissolved solids and chloride concentrations 25 Tables 1. Saturation indices 28 2. -

Wilderness Study Areas

I ___- .-ll..l .“..l..““l.--..- I. _.^.___” _^.__.._._ - ._____.-.-.. ------ FEDERAL LAND M.ANAGEMENT Status and Uses of Wilderness Study Areas I 150156 RESTRICTED--Not to be released outside the General Accounting Wice unless specifically approved by the Office of Congressional Relations. ssBO4’8 RELEASED ---- ---. - (;Ao/li:( ‘I:I)-!L~-l~~lL - United States General Accounting OfTice GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division B-262989 September 23,1993 The Honorable Bruce F. Vento Chairman, Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands Committee on Natural Resources House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: Concerned about alleged degradation of areas being considered for possible inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System (wilderness study areas), you requested that we provide you with information on the types and effects of activities in these study areas. As agreed with your office, we gathered information on areas managed by two agencies: the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLN) and the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service. Specifically, this report provides information on (1) legislative guidance and the agency policies governing wilderness study area management, (2) the various activities and uses occurring in the agencies’ study areas, (3) the ways these activities and uses affect the areas, and (4) agency actions to monitor and restrict these uses and to repair damage resulting from them. Appendixes I and II provide data on the number, acreage, and locations of wilderness study areas managed by BLM and the Forest Service, as well as data on the types of uses occurring in the areas.