Drug Lyrics, the FCC and the First Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Every now and then I am introduced to someone who knows, kind of, who I am and what I do and they instinctively ask, ‘‘How are things at Saga?’’ (they pronounce it ‘‘say-gah’’). I am polite and correct their pronunciation (‘‘sah-gah’’) as I am proud of the word and its history. This is usually followed by, ‘‘What is a ‘‘sah-gah?’’ My response is that there are several definitions — a common one from 1857 deems a ‘‘Saga’’ as ‘‘a long, convoluted story.’’ The second one that we prefer is ‘‘an ongoing adventure.’’ That’s what we are. Next they ask, ‘‘What do you do there?’’ (pause, pause). I, too, pause, as by saying my title doesn’t really tell what I do or what Saga does. In essence, I tell them that I am in charge of the wellness of the Company and overseer and polisher of the multiple brands of radio stations that we have. Then comes the question, ‘‘Radio stations are brands?’’ ‘‘Yes,’’ I respond. ‘‘A consistent allusion can become a brand. Each and every one of our radio stations has a created personality that requires ongoing care. That is one of the things that differentiates us from other radio companies.’’ We really care about the identity, ambiance, and mission of each and every station that belongs to Saga. We have radio stations that have been on the air for close to 100 years and we have radio stations that have been created just months ago. -

The Comment, March 1, 1979

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University The ommeC nt Campus Journals and Publications 1979 The ommeC nt, March 1, 1979 Bridgewater State College Volume 52 Number 5 Recommended Citation Bridgewater State College. (1979). The Comment, March 1, 1979. 52(5). Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/comment/461 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Vol. LII No.5 Bridgewater State College March 1,1979 Students to Receive Minimum by Karen Tobin The Comment attempted to students are getting 1t. Minimum On Tuesday, February 27, contact Dr. Richard Veno, the wage is low enough in these days of President Rondileau announced his Director of the Student Union, Dr. inflation." decision on the campus minimum -Owen McGowan, the Head David Morwick, Financial Aid wage question. Beginning on March Librarian, and David Morwick, the Officer, said that the new minimum 1, all students employed by Financial Aid Officer to find out their wage should not adversely effect the Bridgewater State College will' reactions to Dr. Rondileau's, College Work-Study Program. receive the federal minimum wage announcement. Dr. Vena was out people will simply eaam their money, of $2.90 per hour. (on business) and therefore could more quickly. He noted there is the i. Dr. Rondileau explained the not comment. Dr. McGowen. Head possibility that some of this year's decision, 'We studied the'situation Librarian, saId that the raise in awards may be increased but this is very carefully. We came to the best minimum. -

VAB Member Stations

2018 VAB Member Stations Call Letters Company City WABN-AM Appalachian Radio Group Bristol WACL-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WAEZ-FM Bristol Broadcasting Company Inc. Bristol WAFX-FM Saga Communications Chesapeake WAHU-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WAKG-FM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WAVA-FM Salem Communications Arlington WAVY-TV LIN Television Portsmouth WAXM-FM Valley Broadcasting & Communications Inc. Norton WAZR-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WBBC-FM Denbar Communications Inc. Blackstone WBNN-FM WKGM, Inc. Dillwyn WBOP-FM VOX Communications Group LLC Harrisonburg WBRA-TV Blue Ridge PBS Roanoke WBRG-AM/FM Tri-County Broadcasting Inc. Lynchburg WBRW-FM Cumulus Media Inc. Radford WBTJ-FM iHeart Media Richmond WBTK-AM Mount Rich Media, LLC Henrico WBTM-AM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WCAV-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WCDX-FM Urban 1 Inc. Richmond WCHV-AM Monticello Media Charlottesville WCNR-FM Charlottesville Radio Group (Saga Comm.) Charlottesville WCVA-AM Piedmont Communications Orange WCVE-FM Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVE-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVW-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCYB-TV / CW4 Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WCYK-FM Monticello Media Charlottesville WDBJ-TV WDBJ Television Inc. Roanoke WDIC-AM/FM Dickenson Country Broadcasting Corp. Clintwood WEHC-FM Emory & Henry College Emory WEMC-FM WMRA-FM Harrisonburg WEMT-TV Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WEQP-FM Equip FM Lynchburg WESR-AM/FM Eastern Shore Radio Inc. Onley 1 WFAX-AM Newcomb Broadcasting Corporation Falls Church WFIR-AM Wheeler Broadcasting Roanoke WFLO-AM/FM Colonial Broadcasting Company Inc. Farmville WFLS-FM Alpha Media Fredericksburg WFNR-AM/FM Cumulus Media Inc. -

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2016 Annual Report 2016 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Well…. here we go. This letter is supposed to be my turn to tell you about Saga, but this year is a little different because it involves other people telling you about Saga. The following is a letter sent to the staff at WNOR FM 99 in Norfolk, Virginia. Directly or indirectly, I have been a part of this station for 35+ years. Let me continue this train of thought for a moment or two longer. Saga, through its stockholders, owns WHMP AM and WRSI FM in Northampton, Massachusetts. Let me share an experience that recently occurred there. Our General Manager, Dave Musante, learned about a local grocery/deli called Serio’s that has operated in Northampton for over 70 years. The 3rd generation matriarch had passed over a year ago and her son and daughter were having some difficulties with the store. Dave’s staff came up with the idea of a ‘‘cash mob’’ and went on the air asking people in the community to go to Serio’s from 3 to 5PM on Wednesday and ‘‘buy something.’’ That’s it. Zero dollars to our station. It wasn’t for our benefit. Community outpouring was ‘‘just overwhelming and inspiring’’ and the owner was emotionally overwhelmed by the community outreach. As Dave Musante said in his letter to me, ‘‘It was the right thing to do.’’ Even the local newspaper (and local newspapers never recognize radio) made the story front page above the fold. Permit me to do one or two more examples and then we will get down to business. -

Request for Proposal: Charlottesville Radio Group 2015 Community Awareness Grant

Request for Proposal: Charlottesville Radio Group 2015 Community Awareness Grant Our commitment: the number one priority is our clients; serving the businesses and listeners of Charlottesville with quality programming and superior services. Charlottesville Radio Group Community Awareness Grant Background The Charlottesville Radio Group is a locally operated broadcast group that runs five radio stations in Charlottesville (WCNR, WINA, WQMZ, WVAX, and WWWV). Our radio stations have a long history of supporting and working with area nonprofit organizations in the realm of marketing and public relation campaigns. While there are a number of barriers that hinder nonprofits in the Charlottesville/Albemarle area, one frequently cited is the inability to adequately convey the organization’s message to the community. It is our desire to assist four area nonprofit organizations in launching and implementing a consistent, long-term marketing campaign via a Charlottesville Radio Group Community Awareness Grant (CRGCAG). This grant (established in 2001) is issued to promote an organization and their mission or message through the use of our five radio stations. Process Overview The review process will have two rounds. A panel comprised of a cross section of Charlottesville Radio Group employees will initially review all submissions. This panel will forward up to seven submissions to the final selection committee for review. The final selection committee will be comprised of key community leaders. Recipients will be chosen based on the organization’s history of community service, connection to the community, mission within the community, demonstration of need, population served and geographic region served. Each recipient of a Charlottesville Radio Group Community Awareness Grant will receive a yearlong series of sixty-second radio announcements on-air (valued at $59,488.00) and bonus commercials that will air on the online streams of WCNR, WWWV, WQMZ and WINA (valued at $10,290). -

How Far Is Too Far? the Line Between "Offensive" and "Indecent" Speech

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 49 Issue 2 Article 4 2-1997 How Far Is Too Far? The Line Between "Offensive" and "Indecent" Speech Milagros Rivera-Sanchez University of Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Rivera-Sanchez, Milagros (1997) "How Far Is Too Far? The Line Between "Offensive" and "Indecent" Speech," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 49 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol49/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How Far Is Too Far? The Line Between "Offensive" and "Indecent" Speech Milagros Rivera-Sanchez* I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 327 II. SCOPE AND METHOD .............................. 329 m. INDECENCY AND THE FCC's COMPLAINT INVESTIGATION PROCESS ........................... 332 A. Definition of Indecency ..................... 332 B. Context ................................ 333 C. The Complaint InvestigationProcess ............ 336 IV. DISMISSED COMPLAINTS ........................... 337 A. Expletives or Vulgar Words ................... 337 B. Descriptionsof Sexual or Excretory Activites or Organs ....................... -

FM16 Radio.Pdf

63 Pleasant Hill Road • Scarborough P: 885.1499 • F: 885.9410 [email protected] “Clean Up Cancer” For well over a year now many of us have seen the pink van yearly donation is signifi cant and the proceeds all go to the cure of Eastern Carpet and Upholstery Cleaning driving around York for women’s cancer. and Cumberland counties, and we may have asked what’s it all about. To clear up this question I spent some time with Diane Diane was introduced to breast cancer early in life when her Gadbois at her home and asked her some very personal questions mother had a radical mastectomy. She remembers her mother’s that I am sure were diffi cult to answer. You see, George and Diane doctor telling her sister and her “one of you will have cancer.” Gadbois are private people who give more than their share back Not a pleasant thought at the time, but it stuck with Diane and to the community, and the last thing they want is to be noticed saved her life. Twice, after the normal tests and screenings for for their generosity. They started Eastern Carpet and Upholstery cancer, Diane received a clean bill of health and relatively soon Cleaning 40 years ago on a wish and a prayer and now have the after, while doing a self-examination, found a lump. Not once but largest family-run carpet cleaning and water damage restoration twice! Fortunately they were found in time, and Diane is doing company in the area. fi ne, but she wants to get the message out that as important as it is to get regular screenings, it is equally as important to be your own Back to the pink van! If you notice on the rear side panels are advocate and make double sure with a self-examination. -

For Immediate Release August 2014

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUGUST 2014 CONTACT: Lexie Boris | 434-971-7515 | [email protected] | pcasa.org Charlottesville Radio Group Gives Piedmont CASA Kids a Big Voice Piedmont CASA is thrilled to announce that the Charlottesville Radio Group has awarded us a Community Awareness Grant consisting of over $65,000 worth of advertising on five radio stations: Newsradio 1070 (WINA), Lite Rock Z95.1 (WQMZ), ESPN Radio 1450 (WVAX), 106.1 The Corner (WCNR), and 97.5 3WV (WWWV). This generous grant means that Piedmont CASA can reach tens of thousands of Charlottesville area radio listeners every day for an entire year. That on-air presence will enable us to recruit more Volunteers, enhance public awareness of child abuse and neglect as well as its impact on our community, and keep the public informed about important new initiatives to help these young victims. A campaign using this grant to recruit volunteers for Piedmont CASA began this month, and has already made a big difference. Because the grant gives Piedmont CASA air time through July 31st, 2015, we will be able to do a second volunteer recruitment campaign in the spring, and several public awareness campaigns between now and then, such as Fostering Futures. Fostering Futures is a new training program that is being implemented this year. It will enable Volunteers to advocate more effectively for older youth in foster care so they develop the connections, resources, and supports they need to make a safer and more effective transition out of the system, and into independent living. “This grant provides an incredible opportunity for us to reach an enormous audience,” said Piedmont CASA President Alicia Lenahan, “People who may ultimately decide to become CASA Volunteers.” Founded in 1995, Piedmont CASA trains community Volunteers to advocate for over 200 abused and neglected children each year before the courts of the 16th Judicial District of Virginia. -

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 34 • NUMBER 1 Wednesday, January 1, 1969 • Washington, D.C

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 34 • NUMBER 1 Wednesday, January 1, 1969 • Washington, D.C. Pages 1-30 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Agriculture Department Atomic Energy Commission Civil Aeronautics Board Commodity Credit Corporation Consumer and Marketing Service Federal Aviation Administration Federal Communications Com mission Federal Highway Administration Indian Affairs Bureau Interagency Textile Administrative Committee Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau Maritime Administration Public Health Service Reclamation Bureau Securities and Exchange Commission Social and Rehabilitation Service Treasury Department Detailed list of Contents appears inside. MICROFILM EDITION FEDERAL REGISTER 35mm MICROFILM Complete Set 1936-87,167 Rolls $1,162 Vol. Year Price Vol. Year Price Vol. Year Price 1 1936 $8 12 1947 $26 23 1958 $36 2 1937 10 13 1948 27 24 1959 40 3 1938 9 14 1949 22 25 1960 49 4 1939 14 15 1950 26 26 1961 46 5 1940 15 16 1951 43 27 1962 50 6 1941 20 17 1952 35 28 1963 49 7 1942 35 18 1953 32 29 1964 57 8 1943 52 19 1954 39 30 1965 58 9 1944 42 20 1955 36 31 1966 61 10 1945 43 21 1956 38 32 1967 64 11 1946 42 22 1957 38 Order Microfilm Edition from Publications Sales Branch National Archives and Records Service Washington, D.C. 20408 Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on Sundays, Mondays, or FEDERALWREGISTER on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the. Office of the Federal Register, National a. g Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail address National Area Code 202 «34 Phone 962-8626 * (Junto ’ Archives Building, Washington, D.C. -

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Letter to Our Fellow Shareholders

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Although another year has zoomed by, 2015 seems like it was 2014 all over again. The good news is that we are still here and we have used some of our excess cash for significant and cogent acquisitions. We will get into that shortly, but first a small commercial about broadcasting. I have always, since childhood, been fascinated by magic and magicians. I even remember, very early in my life, reading the magazine PARADE that came with the Sunday newspaper. Inside the back page were small ads that promoted everything from the ‘‘best new rug shampooer’’ to one that seemed to run each week. It was about a three inch ad and the headline always stopped me -- ‘‘MYSTERIES OF THE UNIVERSE REVEALED!’’...Wow... All I had to do was write away and some organization called the Rosicrucian’s would send me a pamphlet and correspondent courses revealing all to me. Well, my mother nixed that idea really fast. It didn’t stop my interest in magic and mysticism. I read all I could about Harry Houdini and, especially, Howard Thurston. Orson Welles called Howard Thurston ‘‘The Master’’ and, though today he is mostly forgotten except among magicians, he was truly a gifted magician and a magical performer. His competitor was Harry Houdini, whose name survived though his magic had a tragic end. If you are interested, you should take some time and research these two performers. In many ways, their magic and their shows tie into what we do today in both radio and TV. -

1982-07-17 Kerrville Folk Festival and JJW Birthday Bash Page 48

BB049GREENLYMONT3O MARLk3 MONTY GREENLY 0 3 I! uc Y NEWSPAPER 374 0 E: L. M LONG RE ACH CA 9 0807 ewh m $3 A Billboard PublicationDilisoar The International Newsweekly Of Music & Home Entertainment July 17, 1982 (U.S.) AFTER `GOOD' JUNE AC Formats Hurting On AM Dial Holiday Sales Give Latest Arbitron Ratings Underscore FM Penetration By DOUGLAS E. HALL Billboard in the analysis of Arbitron AM cannot get off the ground, stuck o Retailers A Boost data, characterizes KXOK as "being with a 1.1, down from 1.6 in the win- in ter and 1.3 a year ago. ABC has suc- By IRV LICHTMAN NEW YORK -Adult contempo- battered" by its FM competitors formats are becoming as vul- AC. He notes that with each passing cessfully propped up its adult con- NEW YORK -Retailers were while prerecorded cassettes contin- rary on the AM dial as were top book, the age point at which listen - temporary WLS -AM by giving the generally encouraged by July 4 ued to gain a greater share of sales, nerable the same waveband a ership breaks from AM to FM is ris- FM like call letters and simulcasting weekend business, many declaring it according to dealers surveyed. 40 stations on few years ago, judging by the latest ing. As this once hit stations with the maximum the FCC allows. The maintained an upward sales trend Business was up a modest 2% or spring Arbitrons for Chicago, De- teen listeners, it's now hurting those result: WLS -AM is up to 4.8 from evident over the past month or so. -

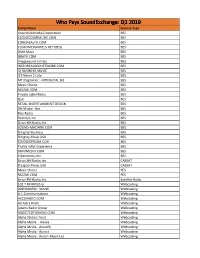

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media