How Far Is Too Far? the Line Between "Offensive" and "Indecent" Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Comment, March 1, 1979

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University The ommeC nt Campus Journals and Publications 1979 The ommeC nt, March 1, 1979 Bridgewater State College Volume 52 Number 5 Recommended Citation Bridgewater State College. (1979). The Comment, March 1, 1979. 52(5). Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/comment/461 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Vol. LII No.5 Bridgewater State College March 1,1979 Students to Receive Minimum by Karen Tobin The Comment attempted to students are getting 1t. Minimum On Tuesday, February 27, contact Dr. Richard Veno, the wage is low enough in these days of President Rondileau announced his Director of the Student Union, Dr. inflation." decision on the campus minimum -Owen McGowan, the Head David Morwick, Financial Aid wage question. Beginning on March Librarian, and David Morwick, the Officer, said that the new minimum 1, all students employed by Financial Aid Officer to find out their wage should not adversely effect the Bridgewater State College will' reactions to Dr. Rondileau's, College Work-Study Program. receive the federal minimum wage announcement. Dr. Vena was out people will simply eaam their money, of $2.90 per hour. (on business) and therefore could more quickly. He noted there is the i. Dr. Rondileau explained the not comment. Dr. McGowen. Head possibility that some of this year's decision, 'We studied the'situation Librarian, saId that the raise in awards may be increased but this is very carefully. We came to the best minimum. -

Education and the Brain: a Bridge Too Far

Education and the Brain: A Bridge Too Far j OHN T. BRUE R Educational Researcher, Vol . 26, No . 8, pp. 4-16 place, that indirectly link brain function with educational practice. There is a well-established bridge, now nearly 50 years old, between education and cognitive psychology. rain science fascinates teachers and educators, just as There is a second bridge, only around 10 years old, between it fascinates all of us. When I speak to teachers about cognitive psychology and neuroscience. This newer bridge Bapplications of cognitive science in the classroom, is allowing us to see how mental functions map onto brain there is always a question or two about the right brain ver structures. When neuroscience does begin to provide use sus the left brain and the educational promise of brain ful insights for educators about instruction and educational based curricula. I answer that these ideas have been practice, those insights will be the result of extensive traffic around for a decade, are often based on misconceptions and over this second bridge. Cognitive psychology provides the overgeneralizations of what we know about the brain, and only firm ground we have to anchor these bridges. It is the have little to offer to educators (Chipman, 1986). Educa only way to go if we eventually want to move between ed tional applications of brain science may come eventually, ucation and the brain. but as of now neuroscience has little to offer teachers in terms of informing classroom practice. There is, however, a The Neuroscience and Education Argument science of mind, cognitive science, that can serve as a basic The neuroscience and education argument relies on and science for the development of an applied science of learn embellishes three important and reasonably well-estab ing and instruction. -

Where Do All the Lovers Go?”–The Cultural Politics of Public Kissing in Mumbai, India (1950–2005)

DOI: 10.1111/johs.12205 ORIGINAL ARTICLE “Where do all the lovers go?”–The Cultural Politics of Public Kissing in Mumbai, India (1950–2005) Sneha Annavarapu Doctoral Candidate, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA Abstract Correspondence Public expressions of sexual intimacy have often been sub- Sneha Annavarapu, Doctoral Candidate, ject to moral censure and legal regulation in modern India. Department of Sociology, University of Chicago, USA. While there is literature that analyzes the cultural‐political Email: [email protected] logics of censorship and sexual illiberalism in India, the dis- courses of sympathy towards public displays of intimacy has not received as much critical attention. In this paper, I take the case of one representative discursive space offered by a popular English newspaper and show how the figure of the ‘kissing couple’ became an important entity in larger discussions about the state of urban development, the role of pleasure in the city, and the imagination of a “modern” Mumbai. “Public kissing is just not Indian”–Pramod Navalkar, Indian politician1 1 | INTRODUCTION In most Indian cities and towns, kissing in public places has been considered culturally inappropriate. The argument against men and women kissing, holding hands, and hugging in public is that it is culturally inappropriate, disrespectful to community standards, and downright ‘obscene’. Although recent protests and campaigns by urban youth2 have begun to offer a sense of organized resistance to traditional norms governing behavior in public spaces, it is common knowledge that couples engaging in ‘public displays of affection’ are often subject to moral policing by local police, political parties, and private citizens. -

HUG Holiday Songbook a Collection of Christmas Songs Used by the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

STRUM YULETIDE EDITION The HUG Holiday Songbook A collection of Christmas songs used by the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada All of the songs contained within this book are for research and personal use only. Many of the songs have been simplified for playing at our club meetings. General Notes: ¶ The goal in assembling this songbook was to pull together the bits and pieces of music used at the monthy gatherings of the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) ¶ Efforts have been made to make this document as accurate as possible. If you notice any errors, please contact us at http://halifaxukulelegang.wordpress.com/ ¶ The layout of these pages was approached with the goal to make the text as large as possible while still fitting the entire song on one page ¶ Songs have been formatted using the ChordPro Format: The Chordpro-Format is used for the notation of Chords in plain ASCII-Text format. The chords are written in square brackets [ ] at the position in the song-text where they are played: [Em] Hello, [Dm] why not try the [Em] ChordPro for [Am] mat ¶ Many websites and music collections were used in assembling this songbook. In particular, many songs in this volume were used from the Christmas collections of the Seattle Ukulele Players Association (SUPA), the Bytown Ukulele Group (BUG), Richard G’s Ukulele Songbook, Alligator Boogaloo and Ukulele Hunt ¶ Ukilizer (http://www.ukulizer.com/) was used to transpose many songs into ChordPro format. ¶ Arial font was used for the song text. Chord diagrams were created using the chordette fonts from Uke Farm (http://www.ukefarm.com/chordette/) HUG Holiday Songbook - Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) 2015 (http://halifaxukulelegang.wordpress.com) Page 2 Table of Contents All I Want for Christmas is My Two Front Teeth............................................................. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Refashioning the Sociopolitical in Spanish Modernist Literature (1902-1914)

Refashioning the Sociopolitical in Spanish Modernist Literature (1902-1914) By Ricardo Lopez A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dru Dougherty, Chair Professor Ivonne del Valle Professor Robert Kaufman Fall 2015 Abstract Refashioning the Sociopolitical in Spanish Modernist Literature (1902-1914) by Ricardo Lopez Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures with a Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Dru Dougherty, Chair In this dissertation I argue that the modernist breakthroughs achieved by José Martínez Ruiz’s La voluntad (1902), Ramón del Valle-Inclán’s Sonata de otoño (1902), and Miguel de Unamuno’s Niebla (1914) emerged as a response to the shortsightedness of the revolutionary politics that had taken root in Restoration Spain. I examine how these writers take the historical materials of their sociopolitical world—its tropes and uses of language—and reconstellate them as artworks in which the familiar becomes estranged and reveals truths that have been obscured by the ideological myopia of Spain’s radicalized intellectuals. Accordingly, I demonstrate that the tropes, language, and images that constitute La voluntad, Niebla, and Sonata de otoño have within them a historical sediment that turns these seemingly apolitical works into an “afterimage” of Spain’s sociopolitical reality. Thus I show how sociopolitical critiques materialize out of the dialectic between historical materials and their artistic handling. Although La voluntad, Sonata de otoño, and Niebla seem to eschew political themes, I contend that they are the product of their authors’ keen understanding of the politics of their moment. -

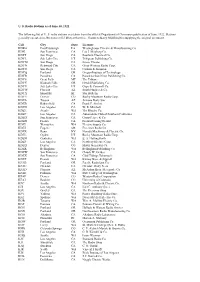

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

Tesi Doct Oral

TESI DOCTORAL UPF/ DOCTORAL TESI 2020 Mapping press’s political ideology Jucinara Schena A content analysis of editorial articles from the most read Brazilian online newspapers TESI DOCTORAL UPF/2020 newspapers the online from mostBrazilian read ofeditorialA content articles analysis politicalideology Mapping press’s Jucinara Schena Mapping press’s political ideology A content analysis of editorial articles from the most read Brazilian online newspapers Jucinara Schena DOCTORAL THESIS UPF / 2020 THESIS DIRECTOR Dra. Núria Almiron DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA ii memento mori ∞ iv We will need writers who can remember freedom. The realists of a larger reality. ― Ursula Le Guin to my mother Gessi Neusa Gnoatto Schena & in memory of my father, Jorge Schena. v vi Acknowledgements Writing the acknowledgements is the last part to be completed in this work, although it is the first to appear. The order is justified now after the research work is accomplished, and it comes the singular moment to look back at these years of the PhD program. With no spare, I must express my gratitude to the ones walking with me this tortuous, nonetheless valuable and fruitful route. Without them, absolutely none of this would have been possible. My mother may have no idea about the research as I wrote in all these pages, but she is present in every letter. She was prohibited from pursuing her studies when her dream was to be a teacher – she was able to go only until the 3rd year of primary school. And always said she would not make enough to leave me an inheritance, but she would make her best to help me to study whatever I decided for as long as I wanted. -

C L Fl S: FCC 8L ,8 FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

C L fl s: FCC 8L_,8 FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 34 329 In the Matter of ) Amendment of Part 73 of the ) Commission's Rules and Regulations ) BC Docket No. 79-265 1V Concerning the Nighttime Power ) Limitations for Class IV AM ) Broadcast Stations ) RERT AND ORDER (Proceeding Terminated) Adopted: March 15, i98+ ; Released: March 23, 198Lf By the Commission: INTRODUCTION 1. The Commission has before it the Notice of Proposed Rule Making in this proceeding adopted October 19, 1983, 48 FR 50571; November 2, 1983, and the comments and reply comments filed in response to the Notice. In order to place the Notice proposal to increase the nighttime power of Class IV AN stations in context, some background information is necessary. By Report and Order, FCC 58-573, Power Limitations of Class IV Stations, 17 RR 1541 (1958), released June 2, 1958, the Commission increased the maximum permissible daytime power for Class IV AM broadcast stations from 250 watts to 1 kilowatt. This action was taken in response to a petition for rule making filed April 3, 1956 by Community Broadcasters Association, Inc. ("CBA"), an organization representing Class IV AN stations. The across-the-board approach to the power increase was chosen to improve reception of these stations while maintaining their existing coverage areas. CBA also had petitioned for a power increase at night as well, but this could not then be pursued because of international treaty constraints. Recent international developments have suggested that these international restrictions against increasing nighttime power will likely be removed at an early date. -

FM16 Radio.Pdf

63 Pleasant Hill Road • Scarborough P: 885.1499 • F: 885.9410 [email protected] “Clean Up Cancer” For well over a year now many of us have seen the pink van yearly donation is signifi cant and the proceeds all go to the cure of Eastern Carpet and Upholstery Cleaning driving around York for women’s cancer. and Cumberland counties, and we may have asked what’s it all about. To clear up this question I spent some time with Diane Diane was introduced to breast cancer early in life when her Gadbois at her home and asked her some very personal questions mother had a radical mastectomy. She remembers her mother’s that I am sure were diffi cult to answer. You see, George and Diane doctor telling her sister and her “one of you will have cancer.” Gadbois are private people who give more than their share back Not a pleasant thought at the time, but it stuck with Diane and to the community, and the last thing they want is to be noticed saved her life. Twice, after the normal tests and screenings for for their generosity. They started Eastern Carpet and Upholstery cancer, Diane received a clean bill of health and relatively soon Cleaning 40 years ago on a wish and a prayer and now have the after, while doing a self-examination, found a lump. Not once but largest family-run carpet cleaning and water damage restoration twice! Fortunately they were found in time, and Diane is doing company in the area. fi ne, but she wants to get the message out that as important as it is to get regular screenings, it is equally as important to be your own Back to the pink van! If you notice on the rear side panels are advocate and make double sure with a self-examination. -

Songs of the Classical Age

Cedille Records CDR 90000 049 SONGS OF THE CLASSICAL AGE Patrice Michaels Bedi soprano David Schrader fortepiano 2 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 049 S ONGS OF THE C LASSICAL A GE FRANZ JOSEF HAYDN MARIA THERESIA VON PARADIES 1 She Never Told Her Love.................. (3:10) br Morgenlied eines armen Mannes...........(2:47) 2 Fidelity.................................................... (4:04) WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART 3 Pleasing Pain......................................... (2:18) bs Cantata, K. 619 4 Piercing Eyes......................................... (1:44) “Die ihr des unermesslichen Weltalls”....... (7:32) 5 Sailor’s Song.......................................... (2:25) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN VINCENZO RIGHINI bt Wonne der Wehmut, Op. 83, No. 1...... (2:11) 6 Placido zeffiretto.................................. (2:26) 7 SOPHIE WESTENHOLZ T’intendo, si, mio cor......................... (1:59) ck Morgenlied............................................. (3:24) 8 Mi lagnerò tacendo..............................(1:37) 9 Or che il cielo a me ti rende............... (3:07) FRANZ SCHUBERT bk Vorrei di te fidarmi.............................. (1:27) cl Frülingssehnsucht from Schwanengesang, D. 957..................... (4:06) CHEVALIER DE SAINT-GEORGES bl L’autre jour à l’ombrage..................... (2:46) PAULINE DUCHAMBGE cm La jalouse................................................ (2:22) NICOLA DALAYRAC FELICE BLANGINI bm Quand le bien-aimé reviendra............ (2:50) cn Il est parti!.............................................. (2:57) -

1982-07-17 Kerrville Folk Festival and JJW Birthday Bash Page 48

BB049GREENLYMONT3O MARLk3 MONTY GREENLY 0 3 I! uc Y NEWSPAPER 374 0 E: L. M LONG RE ACH CA 9 0807 ewh m $3 A Billboard PublicationDilisoar The International Newsweekly Of Music & Home Entertainment July 17, 1982 (U.S.) AFTER `GOOD' JUNE AC Formats Hurting On AM Dial Holiday Sales Give Latest Arbitron Ratings Underscore FM Penetration By DOUGLAS E. HALL Billboard in the analysis of Arbitron AM cannot get off the ground, stuck o Retailers A Boost data, characterizes KXOK as "being with a 1.1, down from 1.6 in the win- in ter and 1.3 a year ago. ABC has suc- By IRV LICHTMAN NEW YORK -Adult contempo- battered" by its FM competitors formats are becoming as vul- AC. He notes that with each passing cessfully propped up its adult con- NEW YORK -Retailers were while prerecorded cassettes contin- rary on the AM dial as were top book, the age point at which listen - temporary WLS -AM by giving the generally encouraged by July 4 ued to gain a greater share of sales, nerable the same waveband a ership breaks from AM to FM is ris- FM like call letters and simulcasting weekend business, many declaring it according to dealers surveyed. 40 stations on few years ago, judging by the latest ing. As this once hit stations with the maximum the FCC allows. The maintained an upward sales trend Business was up a modest 2% or spring Arbitrons for Chicago, De- teen listeners, it's now hurting those result: WLS -AM is up to 4.8 from evident over the past month or so.