New Work: Georg Herold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sigmar Polke

© Kenny Schachter / ROVE Projects LLP Published by ROVE Projects LLP, 2011 First Edition of 1000 copies ISBN 978-0-9549605-3-7 All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted Curated by Adrian, Kai and Kenny Schachter in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise without prior permission from the publisher and artist. The artist retains copyright on all photographs, drawings, notes and text reproduced in this catalogue, except where otherwise noted. All photography except cover and pages 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 39, 40, 48, 54, 57, 60, 75 - 79 by Caspar Stracke and Gabriela Monroy Graphic Design by Gabriela Monroy. Printed in the United Kingdom by Colourset Litho Ltd. Kenny Schachter ROVE Projects LLP Lincoln House 33-34 Hoxton Square London N1 6NN United Kingdom For all enquiries please contact: [email protected] +44 (0)7979 408 914 www.rovetv.net Kenny Schachter ROVE 2012 Stuart Gurr, Rachel Harrison, Ricci Albenda, Rob Pruitt, Brian Clarke, Zaha Hadid, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, Keith Tyson, Barry Reigate, Robert Chambers, Maria Pergay, Arik Levy, Martin Usborne, Tom Dixon, Vito Acconci, Franz West, George Condo, Josh Smith, Joe Bradley, Paul Thek, Sigmar Polke, William Pope.L, Marc Newson, Richard Artschwager, Peter Hujar, Misaki Kawai, Brendan Cass, Richard Woods, Donald Baechler, Keith Coventry, Lars Whelan, Hester Finch, Cain Caser, Muir Vidler, Jasper Joffe & Harry Pye, John Isaacs, Keith Coventry, Marianne Vitale, Simon English, Rod Clark, Mary Heilmann, and Adrian, Kai, Gabriel, Sage and Kenny Schachter, Ilona Rich, Kevbe Otobo, Tom Gould, Harry Rüdham, Alfie Caine, George Morony, Eleni Khouri, Tom Harwood, Ollie Wink, Antonia Osgood, Louis Norman, Matilda Wyman, Jessy Wyman, Katie Wyman, Calum Knight, Eugenie Clive-Worms, Emmanuelle Zaoui and Savannah Murphy. -

Sigmar Polke: 'A Queer Journey...'

Frontier Vol. 43, No. 11, Sep 26 –Oct 2, 2010 SIGMAR POLKE ‘A Queer Journey....’ Ritwika Misra Sigmar Polke, the painter-photographer has died of cancer on June 10. A central protagonist in post-war German art, Polke has been instrumental to bring about the laconic 'Modern Kunst' (the modem art movement from 1968) which was a tread away from the banality of genteel art. Born in 1941 at the height of world war in Lower Silesia, Polke at the age of 12 left the communist east with his family for Dusseldorf where he grew up in prosperity of the West Germany. This formative experience of crossing the borders underpinned his story of art. Satiating his initial artistic craving, being an apprentice in a stained glass factory he went on to study at the Dusseldorf Art Academy from 1961 to 1967. These years opened up a wider avenue for Polke to test his curious aesthetic intellect. The profound influence of his teacher Joseph Beuys shaped Polke's aptitude. As Robert Hughes wrote in Time, "He seems to have got two big things from Beuys: first, the ides of the artist as clown, shaman and alchemist; second, a healthy reluctance to believe in the final value of categories of style. Hence his early parodies of the sacred modes of Modernism." Even while studying at a conventional art academy Polke knew how to defy the laid out norms, imbibing a languid sarcasm in his creative output. In 1963 Polke and two fellow students, Gerhard Richter and Konrad Fischer-Leug, organized an exhibition entitled "Kapitalistischen Realismus" (Capitalist Realism). -

Fall/Winter 2021/22 Fall/Winter 2021/22 We Love Books

FALL/WINTER 2021/22 FALL/WINTER 2021/22 WE LOVE BOOKS. Dear art book enthusiasts, there is something very familiar to these myriad images. We Art has always led the way in undermining the conventional consume, like, and share them, we produce and manipulate media stereotypes of its time. In the project Boobs—Fe:male our own digital pictures, helping create tomorrow’s flood of Bodies in Pictorial History, we have gathered 80 selected visuals, and sometimes our heads are spinning from all that positions to show how artists’ constructions both of the content. female self and of woman as “the other” keep resituating and renegotiating femininity. The book raises vital questions of the Pictures are enchanting and disturbing, emotional and politics of the body, touching on issues of gender, ethnic sentimental, manipulative, educational, and viral. And the membership, and the vulnerability of the ailing body, while digitally networked world lets us experience events around also delving into the history of art and visual culture. the globe as though we were there only seconds after they happen: think only of the storming of the US Capitol, of the Abstraction in art opens up spaces of resonance in which new assailants’ Viking masks and the trophy pictures with which visions can be outlined and existing representations recon- they boasted of their exploits on social media. We have long sidered. Take Birgir Andrésson’s humorously laconic color lived with the awareness that we cannot trust our eyes and panels based on Icelandic nature myths, Je! Sonhouse’s that the pictures that circulate, far from merely representing Black harlequins championing a new consciousness of skin the real world, shape a new reality—to control the flow of color and identity, or, then again, Michael Müller’s so-called images is to hold power. -

Press Kit Sigmar Polke 17/04/2016

PRESS KIT SIGMAR POLKE 17/04/2016 – 06/11/2016 CURATED BY ELENA GEUNA AND GUY TOSATTO 1 About the “Sigmar Polke” exhibition 2 Excerpts from the catalogue 3 Sigmar Polke’s films at the Teatrino di Palazzo Grassi 4 List of works 5 Chronology of Sigmar Polke 6 Exhibition catalogue 7 Biography of the curators PRESS CONTACTS France and international Italy Claudine Colin Communication PCM Studio Thomas Lozinski Via Goldoni 38 28 rue de Sévigné 20129 Milan 75004 Paris Tel : +39 02 8728 6582 Tel : +33 (0) 1 42 72 60 01 [email protected] Fax : +33 (0) 1 42 72 50 23 Paola C. Manfredi [email protected] Cell : +39 335 545 5539 www.claudinecolin.com [email protected] SIGMAR POLKE 1 ABOUT THE “SIGMAR POLKE” EXHIBITION AT PALAZZO GRASSI From April 17 to November 6 2016, Palazzo Grassi will be presenting the first retrospective show in Italy dedicated to Sigmar Polke (1941-2010). Conceived by Elena Geuna and Guy Tosatto, direc- tor of the Musée de Grenoble, in close collaboration with The Estate of Sigmar Polke, the exhibi- tion spans the artist’s entire career from the 1960s to the 2000s and underlines the variety of his artistic practice. It brings together nearly ninety works from the Pinault Collection and numerous other public and private collections. This retrospective is part of Palazzo Grassi’s exhibition programme that alternates thematic exhi- bitions based on the Pinault Collection and personal shows dedicated to major contemporary ar- tists. It marks a double celebration in 2016: the 10th anniversary of the reopening of Palazzo Gras- si by François Pinault and the 30th anniversary of Sigmar Polke’s participation to the 1986 Venice Biennale, when he was awarded the Golden Lion. -

Franz West Born in 1947, in Vienna Biography Died in 2012, Vienna

Franz West Born in 1947, in Vienna Biography Died in 2012, Vienna Education 1970 Commenced artistic activities 1977-82 Studied with Bruno Gironcoli at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna 1992/93 Teaching assignment at the Städelschule, Frankfurt, DE Solo Exhibitions 2019 Tate Modern, London, UK Centre Pompidou, Paris, France Travelling to Tate Modern, London, UK 2018 ‘Franz West’, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. The show will travel to the Tate Modern, London in 2019. 2017 'Artistclub', curated by Harald Krejci, 21er Haus, Vienna Maison des Arts Georges Pompidou, Cajarc, France ‘Les Pommes d’Adam’, Hall Art Foundation, New York Galerie Mezzanin, Geneva, Switzerland ‘Works 1970–2010’, Gagosian Gallery, Geneva, Switzerland 2015 'Franz West: Les Pommes d'Adam', Hall Art Foundation at MASS MoCA, North Adams, US 2014 'Franz West: Where is my eight?', The Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield, UK 2013 Retrospective, Mumok, Vienna 'Franz West: Where is my eight?', Museum fur Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, DE 2012 64 rue de Turenne, 75003 Paris 20/21er Haus, Vienna 18 avenue de Matignon, 75008 Paris Museo Picasso, Malaga, ES [email protected] 'Man with a Ball', Gagosian Gallery, London - 'Zwei Epiphanien', mit Gelatin, Schloss Damtschach, AT Abdijstraat 20 rue de l’Abbaye Brussel 1050 Bruxelles [email protected] 2011 - 'Room in London', ICA, Londres Grosvenor Hill, Broadbent House W1K 3JH London ‘Furniture’, Gagosian Gallery, Athens [email protected] Juana de Aizpuru, Madrid - ‘Der definierte Raum’, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, -

Kerstin Engholm Galerie Schleifmühlgasse 3 A-1040 Wien T +43 1 585 7337 F +43 1 585 7338 [email protected]

kerstin engholm galerie Schleifmühlgasse 3 A-1040 Wien T +43 1 585 7337 F +43 1 585 7338 [email protected] BJÖRN DAHLEM AUA EXTREMA II Opening 14/03/2002 19.00 Duration 15/03 - 04/05/2002 Press Information We are pleased to announce the first solo show of the young German artist Björn Dahlem in Austria. Dahlem, born 1974 in Munich, studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dusseldorf and currently lives in Berlin. "Dahlems spatial installations refer to scientific phenomena and theories, spanning from relativity theory, quantum theory, psychology, philosophy, science fiction to alchemy. Even if his concepts involve quarks and electromagnetic fields, star constellations and rocket constructions, they are playful mechanical settings of an uncertain and unstable parallel world and have not evolved out of high-tech spirit or an unbroken belief in scientific progress. The trash materials Dahlem uses and the virtuosity of his "space/world" settings are beyond anything the viewer might be lead to expect from concepts such as "Black Hole" or "elementary particles". Where Dahlem tries to reach the stars, he constructs - instead of sterile laboratory devices gleaming with chrome - provisory situations and experimental scientific settings which already seem to comprise the failure of the experiment. According to Dahlem, this scepticism is characteristic of his generation. The end of the great utopian theories that have shaped the 20th century has left its mark on young artists. The belief in an "objective" view of the world is shattered. By applying scientific theories to art, Dahlem does not see himself as an "artist who goes into science", but rather perceives his models as parameters for existential questions such as "What am I made of, where do I come from?" etc. -

Sigmar Polke Born 1941 in Oels, Silesia

This document was updated on January 23, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Sigmar Polke Born 1941 in Oels, Silesia. Died 2010 in Cologne, Germany. EDUCATION 1959-1967 Trained as a glass painter 1961-67 Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1966 Sigmar Polke, Galerie René Block, Berlin, May 11 – June 10, 1966 [catalogue] Sigmar Polke on December 10, 1966 in homage to Schmela with Otto Piene, Konrad Lueg, John Latham, Heinz Mack, Gerhard Richter, Galerie Schmela, Düsseldorf, December 9-15, 1966 1967 Sigmar Polke. Zeichnungen und Ölbilder, Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich, January – February 1967 Sigmar Polke: Neue Bilder, Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich, April 4 – 23, 1967 [catalogue] 1968 Sigmar Polke, Galerie René Block, Berlin, as part of Art Cologne, October 1968 Sigmar Polke. Moderne Kunst, Galerie René Block, Berlin, December 14, 1968 – January 16, 1969 1969 Sigmar Polke, Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, Cologne 1970 Sigmar Polke. 24 Hefte, Kabinett für aktuelle Kunst, Bremerhaven, April 25 – May 20, 1970 Sigmar Polke, Konrad Fischer Galerie, Düsseldorf, June 9 – July 2, 1970 Sigmar Polke. Bilder und Zeichnungen, Galerie Toni Gerber, zu Gast im Möbelhaus Teo Jakob, Bern, September – October 1970 Sigmar Polke, Galerie Thomas Borgmann, November – December 1970 Sigmar Polke. Bilder, Galerie Michael Werner, Cologne, November 20, 1970 – January 10, 1971 1971 Sigmar Polke, Galerie Ernst, Hannover, May – June 1971 Sigmar Polke, Konrad Fischer Galerie, -

Wool CV1.Pdf

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955 in Chicago, IL. Lives and works in New York City. Selected Solo Exhibitions 2015 Christopher Wool: Selected Paintings, McCabe Fine Art, Stockholm, Sweden. Inbox: Christopher Wool, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. 2014-2013 Christopher Wool, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY ; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. 2013 Christopher Wool: Works on Paper, 1989-1990, Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. 2012 Christopher Wool, Musée d‘Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France. 2011 Christopher Wool, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. 2010 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. Christopher Wool: Sound on Sound, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL. 2009 Christopher Wool: Editions, Artelier Contemporary, Graz, Austria. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 2009-2008 Christopher Wool: Porto-Köln, Fundação de Serralves: Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. 2008 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY. 2007 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany. Christopher Wool, Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens, Greece. Christopher Wool: Pattern Paintings, 1987–2000, Skarstedt Gallery, New York, NY. 2006 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Christopher Wool, Institut Valencià d‘Arte Modern, Valencia, Spain; Musée d‘Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France. Christopher Wool, Simon Lee Gallery, London, England. Christopher Wool: Artist in Residence, Chianti Foundation, Marfa, TX. Christopher Wool: East Broadway Breakdown, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland. 2005 Christopher Wool, Galleria Christian Stein, Milan, Italy and Gió Marconi, Milan, Italy. 2004 Christopher Wool, Camden Arts Centre, London, England. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 1120 N Ashland Ave., 3rd Floor, Chicago, IL 60622 | Tel. -

Biography Meuser

MEUSER Born 1947 in Essen, Germany Lives and works in Karlsruhe, Germany Since 1992 Professor at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe Education 1968-76 Staatliche Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf (under Joseph Beuys und Erwin Heerich) Studies in Philosophy Solo Exhibitions 2021 Galerie Nordenhake, Mexico City 2020 Skulpturenpark Heidelberg, Heidelberg Dr. Schlau und Dr. Schlauer (together with Jonathan Monk), Meyer Riegger, Karlsruhe Ankaufpräsentation Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe 2019 Galerie Bärbel Grässlin, Frankfurt Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm 2018 Trocknen lassen, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris Meuser – Werke aus den Sammlungen Grässlin und Wiesenauer, Kunstraum Grässlin, St. Georgen Nachspülen, Meyer Riegger, Karlsruhe Abwasser, Galerie Bärbel Grässlin, Frankfurt Kunstraum Grässlin, St. Georgen 2017 Kann ich mich hier auch selbst einweisen?, Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin 2016 Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne Galerie Bärbel Grässlin, Frankfurt 2015 Strubbel die Katz, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Brussels Drei Serien, Drei Skulpturen (with Doris Tsangaris, curated by Cornelius Tittel), Meyer Riegger, Berlin 2014 Herr Ober, zwei Doppelte, Meyer Riegger, Berlin (in collaboration with Galerie Nordenhake) 2013 Sies + Höke Galerie, Dusseldorf Kopfkissen ohne Bettdecke, Meyer Riegger, Karlsruhe 2012 Galerie Bärbel Grässlin, Frankfurt und Erich mittendrin, Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin 2011 Knautsch, Städtische Galerie, Karlsruhe 2009 Wo ist oben?, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2008 Galerie Bärbel Grässlin, Frankfurt Die Frau reitet und das -

Georg Herold and Markus Oehlen

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release January 1993 PROJECTS: GEORG HEROLD AND MARKUS OEHLEN February 6 - March 23, 1993 The Museum of Modern Art opens its next PROJECTS exhibition with the first museum showing in New York of recent work by German artists Georg Herold and Markus Oehlen on February 6, 1993. Organized by Robert Storr, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, PROJECTS: GEORG HEROLD AND MARKUS OEHLEN features strange and inventive objects and images in a variety of mediums. The exhibition remains on view through March 23. Herold and Oehlen are both members of what might be called the third postwar generation of artists in Germany (Joseph Beuys, for example, represents the first, Jbrg Immendorf, Anselm Kiefer, Sigmar Polke, and Gerhard Richter the second). Although their backgrounds differ -- Herold grew up in the East and Oehlen in the West of a divided Germany -- they have in common an appreciation of the absurd that lends their work its disconcerting physicality and its wit. Concentrating on the recent sculpture of both artists and including paintings and wall constructions, the exhibition highlights both the similarities in their basic sensibilities and the vivid differences in their work. The three sculptures that are the centerpiece of this exhibition include Oehlen's two untitled pieces from 1990 and Herold's single work from 1992, titled Pfannkuchentheorie (Cluster Theory). The surrounding paintings and reliefs represent other dimensions of the artists' activities. In his brochure essay, Mr. Storr writes that "...Oehlen and Herold are most at ease 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. -

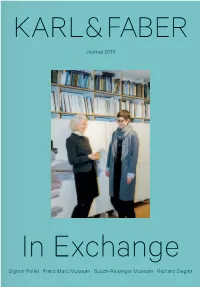

Journal 2019 Sigmar Polke · Franz Marc Museum

KARL&FABER Journal 2019 In Exchange Sigmar Polke · Franz Marc Museum · Busch-Reisinger Museum · Richard Ziegler Dear Reader, The current issue of our journal specifically examines the exchange KARL&FABER maintains with museums and institutions. Ultimately, such insti- tutions thrive because of the people who work in these places and/or those who support them. By focusing on them, it becomes clear once more that col- lectors and institutions, dealers and auction houses all have an extremely sym- biotic relationship that is not always tension-free, but for this, always remains exciting. KARL&FABER keeps close ties with the Franz Marc Museum in Kochel am See and the Busch-Reisinger Museum in Cambridge, near Boston (USA). In our title story, you will learn what strategies their two women museum directors develop in order to achieve distinction alongside the big players. Our column “From KARL&FABER to the Museum” explains to you how a painting by Hein- rich Reinhold and a photograph by Sigmar Polke from our past auctions found their ways to the museum. What is art worth? This question persists as an evergreen: An illustrious discussion round took a stand on this topic last summer in our building. You may well be surprised when you read the summary of the new and astonishing views! We feel privileged to rely on an increasing number of new customers who entrust to us their works of art. This also leads to new sales channels as well as to a further strengthening of our Contemporary Art Department, as you can gather from the various articles in our journal. -

Franz West Born 1947 in Vienna

This document was updated August 5, 2020. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Franz West Born 1947 in Vienna. Died 2012 in Vienna. EDUCATION 1977-1982 Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Dieter Roth and Franz West, Hauser & Wirth, Zurich [two-person exhibition] Franz West, David Zwirner, London Franz West, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Albertusstrasse, Cologne, Germany Franz West: Indoor Sculptures, Omer Tiroche Gallery, London Franz West: Works 1989-2011, Gagosian Gallery, Rome 2018 Franz West, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris [itinerary: Tate Modern, London] [catalogue] Franz West - Parcours hors les murs, Musée Cognacq-Jay, Paris Franz West: Sisyphos Sculptures, Gagosian Gallery, London West World: Thu Van Tran, Franz West, Galerie Natalie Seroussi, Paris [two-person exhibition] 2017 Body Doubles: Hans Josephsohn and Franz West, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, Switzerland [two- person exhibition] Franz West, Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp [catalogue] Franz West: 1970-2010, Gagosian Gallery, Geneva Franz West: The Mathis Esterhazy Collection, Galerie Mezzanin, Geneva 2016 Franz West - ARTISTCLUB, the 21er Haus, Vienna 2015 Franz West, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich 2014-2019 Franz West: Les Pommes d’Adam, Hall Art Foundation at MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts 2014 Franz West, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue] Franz West, Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts 2013 Franz West: Where is My Eight?, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna [itinerary: Museum fur Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt; Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield, England] [catalogue] 2012 Franz West, Philadelphia Museum of Art Man with a Ball, Gagosian Gallery, Britannia Street, London [catalogue] West Reyle / Reyle West: Stolen Fantasy, Kollaboration von Franz West und Anselm Reyle 2010-2012, Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin Zwei Epiphanien.