Arab and European Satellites Over the Maghreb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As It Sides with Qatar, Turkey Tries to Pre-Empt Own Isolation

Roufan Nahhas, Rashmee Roshan Lall, Iman Zayat, Gareth Smyth, Jareer Elass, Stephen Quillen, Mamoon Alabbasi , Yavuz Baydar, Rami Rayess Issue 111, Year 3 www.thearabweekly.com UK £2/ EU €2.50 June 18, 2017 The Middle Saif al-Islam’s East’s smoking release and the problem future of Libya P4 P22 P10 Facing radical Islam P18 As it sides with Qatar, Turkey tries to pre-empt own isolation Mohammed Alkhereiji Saud — “the elder statesman of the 150 additional Turkish troops in Gulf” — should resolve the matter. Doha. There was also a pledge by He needed to maintain a margin of members of the Qatari royal family London manoeuvre to keep his meditation for more investments in Turkey. posture and forestall the risk of An- Galip Dalay, research director at Al s it makes statements kara’s own isolation. Sharq Forum, a Turkish research or- that give the impression Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut ganisation, told the New York Times of a position of mediation Cavusoglu, who met with King Sal- that Turkey was “transitioning from in the Gulf crisis, Turkey man in Mecca on June 16, spoke in neutral mediator to the role of firm- is working to make sure it similarly vague terms. ly supporting the side of Qatar” by isA not the next Muslim Brotherhood- “Although the kingdom is a party voting to send troops to Qatar. affiliated country to face regional in this crisis, we know that King Sal- The Turkish position was in line isolation. man is a party in resolving it,” Cavu- with Ankara’s common affinities A lot has happened since 2015 soglu said at a Doha stopover prior with Doha as another country fac- when Turkish President Recep to his Mecca meeting. -

Les Bouquets De La Tv D'orange Disponibles Sur Tous Vos Écrans

LES BOUQUETS DE LA TV D'ORANGE DISPONIBLES SUR TOUS VOS ÉCRANS LÉGENDE 19 AOÛT AU 06 OCTOBRE 2021 F BOUQUET FAMILLE CS BOUQUET CINE SERIES MC BOUQUET MUSIQUE CLASSIQUE I4 BOUQUET ITALIEN CHAINES INCLUSES [FF] BOUQUET FAMILLE FIBRE(7) (8) FD+ PACK FAMILLE ET DISNEY+ CSM BOUQUET CINE SERIES MAX INT BOUQUET INTENSE I6 BOUQUET ARABE CHAINES ET BOUQUETS EN OPTION [PKL] PICKLE TV BIS BEIN SPORTS O+N PACK OCS + NETFLIX I1 BOUQUET ANGLOPHONE I7 BOUQUET ARABE MAX SPM BOUQUET SPORTS MAX I3 BOUQUET LUSOPHONE I10 BOUQUET AFRICAIN R CHAINES DISPONIBLES EN REPLAY I11 BOUQUET AFRICAIN MAX PC/ MOBILE CLÉ MOBILE MOBILE CLÉ XBOX(5) PC/MAC XBOX(4) CLÉ TV PC /MAC XBOX(4) MAC TABLETTE TV TABLETTE TABLETTE TV CHAÎNES GRATUITES DE LA TNT R TELETOON+ [FF] w w w w AFRICA 24 w w w w R TF1 HD(5) w w w w R TELETOON+1 [FF] w w w w FRANCE 24 ARABE w w w w R FRANCE 2 HD(5) w w w w AL JAZEERA w w w w R FRANCE 3 HD(5) w w w w DECOUVERTE & ART DE VIVRE MEDI1TV w w w w R CANAL+ (EN CLAIR) w w w w MUSEUM w w w w I24 NEWS w w w w (5) R FRANCE 5 HD w w w w ANIMAUX(3) F, FD+, INT w w w w NHK WORLD w w w w (5) R M6 HD w w w w R CRIME DISTRICT F, FD+, INT HD(4) w w w w TRT WORLD w w w w (5) R ARTE HD w w w w CHASSE ET PÊCHE(3) SPM, F, FD+, INT w w w w (5) C8 HD w w w w R TOUTE L'HISTOIRE(3) F, FD+, INT, [FF] w w w w CHAÎNES LOCALES & REGIONALES (5) R W9 HD w w w w R HISTOIRE TV F, FD+, INT, [FF] HD(4) w w w w CHAINES France 3 NATIONALE w w w w (5) TMC HD w w w w R USHUAÏA TV F, FD+, INT, [FF] HD(4) w w w w TAHITI NUI TELEVISION w w w w TFX HD(5) w w w w R MYZEN TV F, FD+, INT w w w w TELE ANTILLES w w w w (5) R NRJ12 HD w w w w SCIENCE&VIE TV(3) F, FD+, INT, [FF] w w w w MADRAS FM TELEVISION w w w w (5) R LCP/PS HD w w w w R NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC [FF] HD(4) w w w w (5) FRANCE4 HD w w w w R NAT. -

TV-Sat Magazyn Maj 2021.Pdf

01_new.qxd 21-04-25 11:50 Page 1 02_Eutelsat.qxd 21-04-25 11:50 Page 2 C M Y B strona 2 03_04_stopka.qxd 21-04-25 12:03 Page 3 NASZE SPRAWY Nowa stacja naziemna w ofercie TVP ANTENA HD (dawniej SILVER TV), nowa stacja naziemna z portfolio MWE Networks, w ofercie Biura Reklamy TVP. Nadawca wybra³ TVP do sprze- da¿y czasu reklamowego, sponsoringu i akcji niestandardowych. Start stacji planowany jest na 1 maja. ANTENA HD jest now¹ stacj¹, powsta³¹ w wyniku konkursu na zagospo- darowanie wygas³ej koncesji stacji ATM Rozrywka. Dziêki otrzymanej koncesji na nadawanie na MUX-1 stacja bêdzie mieæ ogólnopolski zasiêg. ANTENA HD, znana wczeœniej pod robocz¹ nazw¹ SILVER TV, jest od- Najnowocześniejszy powiedzi¹ na rosn¹c¹ si³ê zakupow¹ osób po 50. roku ¿ycia. Jest to stacja filmo- wo-rozrywkowa z licznymi elementami lifestylowymi i edukacyjnymi. wóz transmisyjny Sony „Wybór Biura Reklamy TVP jako brokera dla kana³u ANTENA HD by³ dla nas oczywisty – to jedyne biuro reklamy telewizyjnej w Polsce, które przy w Polsacie ka¿dej kampanii reklamowej bierze pod uwagê widowniê 50+. Jestem bardzo Polsat rozwija nowoczesne technologie produkcyjne i transmisyjne. Dziêki zadowolony ze wspó³pracy z Biurem Reklamy TVP i cieszê siê, ¿e dziêki sta- temu bêdzie mo¿na przygotowaæ jeszcze wiêcej najlepszych i najatrakcyjniej- bilnym przychodom reklamowym mo¿emy rozwijaæ prawdziwie polsk¹ i nieza- szych treœci i programów dla widzów w Polsce, które mo¿na bêdzie ogl¹daæ le¿n¹ grupê medialn¹, która ju¿ nied³ugo bêdzie te¿ nadawa³a ogólnopolski ka- w dowolnie wybrany przez siebie sposób – czy to w telewizji, czy przez Internet. -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

LES CHAÎNES TV by Dans Votre Offre Box Très Haut Débit Ou Box 4K De SFR

LES CHAÎNES TV BY Dans votre offre box Très Haut Débit ou box 4K de SFR TNT NATIONALE INFORMATION MUSIQUE EN LANGUE FRANÇAISE NOTRE SÉLÉCTION POUR VOUS TÉLÉ-ACHAT SPORT INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE MULTIPLEX SPORT & ÉCONOMIQUE EN VF CINÉMA ADULTE SÉRIES ET DIVERTISSEMENT DÉCOUVERTE & STYLE DE VIE RÉGIONALES ET LOCALES SERVICE JEUNESSE INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE CHAÎNES GÉNÉRALISTES NOUVELLE GÉNÉRATION MONDE 0 Mosaïque 34 SFR Sport 3 73 TV Breizh 1 TF1 35 SFR Sport 4K 74 TV5 Monde 2 France 2 36 SFR Sport 5 89 Canal info 3 France 3 37 BFM Sport 95 BFM TV 4 Canal+ en clair 38 BFM Paris 96 BFM Sport 5 France 5 39 Discovery Channel 97 BFM Business 6 M6 40 Discovery Science 98 BFM Paris 7 Arte 42 Discovery ID 99 CNews 8 C8 43 My Cuisine 100 LCI 9 W9 46 BFM Business 101 Franceinfo: 10 TMC 47 Euronews 102 LCP-AN 11 NT1 48 France 24 103 LCP- AN 24/24 12 NRJ12 49 i24 News 104 Public Senat 24/24 13 LCP-AN 50 13ème RUE 105 La chaîne météo 14 France 4 51 Syfy 110 SFR Sport 1 15 BFM TV 52 E! Entertainment 111 SFR Sport 2 16 CNews 53 Discovery ID 112 SFR Sport 3 17 CStar 55 My Cuisine 113 SFR Sport 4K 18 Gulli 56 MTV 114 SFR Sport 5 19 France Ô 57 MCM 115 beIN SPORTS 1 20 HD1 58 AB 1 116 beIN SPORTS 2 21 La chaîne L’Équipe 59 Série Club 117 beIN SPORTS 3 22 6ter 60 Game One 118 Canal+ Sport 23 Numéro 23 61 Game One +1 119 Equidia Live 24 RMC Découverte 62 Vivolta 120 Equidia Life 25 Chérie 25 63 J-One 121 OM TV 26 LCI 64 BET 122 OL TV 27 Franceinfo: 66 Netflix 123 Girondins TV 31 Altice Studio 70 Paris Première 124 Motorsport TV 32 SFR Sport 1 71 Téva 125 AB Moteurs 33 SFR Sport 2 72 RTL 9 126 Golf Channel 127 La chaîne L’Équipe 190 Luxe TV 264 TRACE TOCA 129 BFM Sport 191 Fashion TV 265 TRACE TROPICAL 130 Trace Sport Stars 192 Men’s Up 266 TRACE GOSPEL 139 Barker SFR Play VOD illim. -

Chaines De La France

Chaines de la France CORONAVIRUS TF1 TF1 HEURE LOCALE -6 M6 M6 HEURE LOCALE -6 FRANCE O FRANCE 0 -6 FRANCE 1 ST-PIERRE ET MIQUELON FRANCE 2 FRANCE 2-6 FRANCE 3 FRANCE 3 HEURE LOCALE -6 FRANCE 4 FRANCE 4-6 FRANCE 5 FRANCE 5-6 BFM LCI EURONEWS TV5 CNEWS FRANCE 24 LCP PARI C8 C8 -6 W9 W9 HEURE LOCALE -6 FILM DE LA SÉRIE TF1 6TER PREMIÈRE DE PARIS 13E RUE TFX COMÉDIE PLUS DISTRICT DU CRIME SYFY FR ALTICE STUDIO POLAIRE + CANAL PARAMOUNT DÉCALE PARAMOUNT CLUB DE SÉRIE WARNER BREIZH NOVELAS NOLLYWOOD FR ÉPIQUE DE NOLLYWOOD A + TCM CINÉMA TMC TEVA HISTOIRE DE LA RCM AB1 CSTAR ACTION E! CHERIE 25 NRJ 12 OCS GEANTS OCS CHOC OCS MAX CANAL + CANAL + DECALE SÉRIE CANAL + CANEL + FAMILLE CINÉ + PREMIER CINÉ + FRISSON CINÉ + ÉMOTION CINÉ + CLASSIQUE CINÉ + FAMIZ CINÉ + CLUB ARTE USHUAIA VOYAGE GÉOGRAPHIQUE NATIONALE NATIONAL WILD CHAÎNE DE DÉCOUVERTE ID DE DÉCOUVERTE FAMILLE DE DÉCOUVERTE DÉCOUVERTE SC MUSÉE SAISONS CHASSE ET PECHE ANIMAUX PLANETE + PLANETE + CL PLANÈTE A ET E RMC DECOUVERTE TOUTE LHISTOIRE HISTOIRE MON TÉLÉVISEUR ZEN CSTAR HITS BELGIQUE PERSONNES NON STOP CLIQUE TV VICE TV RANDONNÉE RFM FR MTV DJAZZ MCM TRACE NRJ HITS MTV HITS MUSIQUE M6 Voici la liste des postes en français Québec inclus dans le forfait Diablo Liste des canaux FRENCH Québec TVA MONTRÉAL TVA MONTRÉAL WEB TVA SHERBROOKE TVA QUÉBEC TVA GATINEAU TVA TROIS RIVIERE WEB TVA HULL WEB TVA OUEST NOOVO NOOVO SHERBROOKE WEB NOOVO TROIS RIVIERE WEB RADIO CANADA MONTRÉAL ICI TELE WEB RADIO CANADA OUEST RADIO CANADA VANCOUVER RADIO CANADA SHERBROOKE RADIO CANADA QUÉBEC RADIO CANADA -

Introduction

RAPPORT 12ème Salon Professionnel International de l’Industrie « Alger Industries » Du 07 au 10 Octobre 2018. INTRODUCTION : La douzième édition du Salon Professionnel International « Alger industries », s’est tenue du dimanche 07 au mercredi 10 Octobre 2018, au pavillon AHAGGAR « A »sur le site du Palais des Expositions SAFEX au Pins Maritimes à El Mohammadia, Alger. « Alger industries», organisé par Batimatec Expo, en partenariat avec la Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie de la Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur (CCI PACA) et le Club d’Affaires pour le Développement des Entreprises Françaises en Algérie (CADEFA), est une manifestation économique et commerciale dédiée aux secteurs de l’industrie et aux nouveautés technologiques, pour appuyer la nouvelle stratégie industrielle nationale édictée en 2007 par les pouvoirs publics. Des entreprises publiques & privées, des organismes de financement, bureau de consulting et d’engineering en provenance de plusieurs régions d’Algérie et de pays étrangers, se sont donnés rendez-vous pour quatre jours d’exposition, une véritable opportunité pour un dia- logue direct avec les industriels leaders dans leurs domaines, cela fut aussi une occasion d’échange d’expériences et d’expertises entre les professionnels de ce segment en plein essor. Grâce à ce rendez-vous incontournable, des groupes industriels ont pu se réunir dans un lieu unique, tels que les groupes : SONATRACH, SONELGAZ, GICA, CONDOR,GETEX, AGM, DIVINDUS, MANAL, CEVITAL, KHERBOUCHE, ENCC, CBMI, et bien d’autres, ayants tous les mêmes attentes stratégiques ; conclure des partenariats, développer l’activité, s’étendre sur de nouvelles plateformes et de nouveaux marchés, dans le but d’accroitre le chiffre d’affaires, et contribuer ainsi à développer l’économie en Algérie. -

Liste Des Chaînes Diablo DIABLO CHANNELS LISTS ALL HD (4000)

Maintenent disponible sur Diablo Pro Liste des chaînes Diablo DIABLO CHANNELS LISTS ALL HD (4000) – The only One Iptv you can rewind on your Favorite Channels 12H – 96H – Le Seul Iptv que vous pouvez faire marche arrière sur vos Canaux Préférés 12H – 96H – Video on demand – Movies – Series – Show (Espanol, English, Français) – Possibility of Recording MAG – DIABLO BOX – T2 – BUZZ – FORMULER *** – Possibilité d’enregistrer MAG- DIABLO BOX – T2 – BUZZ – FORMULER *** – VOD -VIDEOCLUB- FILM/MOVIES ARABIC(300+) – FILM/MOVIES ENGLISH (2000+) – FILM/MOVIES FRANCAIS (2000+) – VOD -VIDEOCLUB- PELICULA ESPANOL(20+) – KIDS ENGLISH (80+) – KIDS FRANCAIS (300+) – VOD -VIDEOCLUB- TV SHOWS ENGLISH (150+) – SERIES FRANCAIS (150+) – VOD -VIDEOCLUB- SPORTS – DOCUMENTARY/DOCUMENTAIRE – RAMADAN – SPECTACLES HUMOUR – COFFRET Diablo Channel List § Canaux FRENCH (212) § Canaux FRENCH QUEBEC § Canaux UTC FRENCH (17) § Canaux ARABIC (449) § Canaux UTC ARABIC (50) § Canaux CANADA ENGLISH (166) § Canaux USA ENGLISH (229) § Canaux SPORTS (178) § Canaux UNITED KINGDOM (113) § Canaux KIDS (52) § Canaux AFRICA (260) § Canaux HAITI (8) § Canaux TURKISH & ARMANIA (34) § Canaux ROMANIA (97) § Canaux PORTUGUESE (120) § Canaux BRAZIL (114) § Canaux ESPANA (163) § Canaux NEDERLAND (86) § Canaux ITALIAN (279) § Canaux CZECH REPUBLIC (90) § Canaux LATINO (644) § Canaux IRAN (52) § Canaux BELGIUM (30) § Canaux FILIPINO (18) § Canaux SPORTS ON DEMAND (145) § Canaux SPECIAL EVENTS (8) § Canaux MAJIK FILM / MOVIES (21) § Canaux GREEK (73) § Canaux CARAIBE (86) § Canaux XXX (88) -

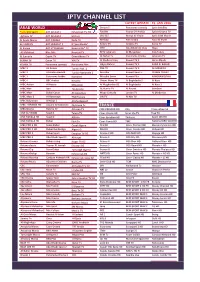

Iptv Channel List Latest Update : 15

IPTV CHANNEL LIST LATEST UPDATE : 15. JAN 2016 ARAB WORLD Dream 2 Panorama comedy Syria Satellite *new Nile Sport ART AFLAM 1 Echourouk TV HD Fatafet France 24 Arabia Syrian Drama TV Aghapy TV ART AFLAM 2 Elsharq LBC SAT Rusiya Al-Yaum Syria 18th March Al Aoula Maroc ART CINEMA Kaifa TV Melody FOX arabia Nour El Sham AL HANEEN ART HEKAYAT 2 N*geo Abuda* Future TV Arabica TV Sama TV Al Karma ART H*ZAMANE Noorsat Sh* TV OTV Abu Dhabi AL Oula Heya Al Malakoot Blue Nile Noorsat TV MTV Lebanon Al Mayadeen Iraq Today Al Sumaria Coptic TV Orient News TV Al Nahar Tv Panorama Drama Lebanon TV BENNA TV Coran TV VIN TV Al Rasheed Iraq Kuwait TV 1 Hona Alquds YEMEN TV Panorama comedy Panorama Film Libya Alahrar Kuwait TV 2 SADA EL BALAD MBC 1 AL Arabia Tunisie Nat. 1 DW-TV Kuwait TV 3 AL MASRIYA MBC 2 Al Arabia Hadath Tunisie Nationale 2 Mazzika Kuwait Sport + YEMEN TODAY MBC 3 Euronews Arabia Hannibal Mazzika Zoom Kuwait Plus KAHERAWELNAS MBC 4 BBC Arabia Nessma Orient News TV Al Baghdadia 2 Al Kass MBC Action Al Resala Ettounisia Al Magharibia DZ Al Baghdadia Al Kass 2 MBC Max Iqra Tounessna AL Hurria TV Al Fourat SemSem MBC Masr Dubai Coran Al Janoubiya Moga Comedy Jordan TV Al Ekhbariya MBC Masr 2 Al Haramayn TNN Tunisia ON TV Al Nas TV MBC Bolywood Al Majd 3 Al Moutawasit MBC + DRAMA HD Assuna Annabaouia Zaytouna Tv FRANCE MBC Drama Rahma TV Al Insen TV CINE PREMIER HD City Trace urban hd OSN AL YAWM Saudi 1 Telvza TV Cine+ Classic HD Sci et Vie TV Trek TV OSN YAHALA HD Saudi 2 Attasia Cine+ Emotion HD Thalassa Sport 365 HD OSN YAHALA HD Dubai -

Le Guide Des Chaînes

Le guide des chaînes Retrouvez toutes les chaînes disponibles dans vos bouquets et options TV 27/10/2020 BOUQUET STARTER L’essentiel des chaînes généralistes, information, cinéma et monde ! L'ENORME TV FRANCE 3 non contractuel. 1 TF1 27 FRANCE INFO : 237 452 POITOU-CHARENTES 519 D!Ci TV ALPES 01TV FRANCE 3 2 FRANCE 2 32 56 MTV 453 PROVENCE-ALPES 520 MARITIMA TV FRANCE 3 BFM PARIS BET FRANCE 3 D!Ci TV PROVENCE 3 39 64 454 RHÔNE-ALPES 521 FRANCE 3 4 CANAL+ EN CLAIR 47 FRANCE 24 250 MTV HITS 455 NOUVELLE AQUITAINE 523 ANGERS TV 5 FRANCE 5 48 EURONEWS 254 M6 MUSIC HD 457 CANAL 21 524 TELE NANTES 6 M6 74 TV5 MONDE 255 RFM TV 461 IDF1 525 TV VENDÉE 7 ARTE 103 LCP-AN 24/24 256 NRJ HITS 464 TELE BOCAL 527 LA CHAINE NORMANDE 8 C8 104 PUBLIC SENAT 24/24 98 BFM LYON 465 TELE PLAISANCE 533 TV TOURS KTO TELIF - VIA 9 W9 179 431 FRANCE 3 ALPES 468 GRAND PARIS 537 TELE PAESE 10 TMC 21 L'EQUIPE 432 FRANCE 3 ALSACE 469 TV78 538 VIÀ31 11 TFX 129 SPORT EN FRANCE 433 FRANCE 3 AQUITAINE 477 TELE GRENOBLE 539 VIÀ66 12 NRJ12 89 SFR ACTU 434 FRANCE 3 AUVERGNE 478 TL7 SAINT ETIENNE 541 CNN INTERNATIONAL FRANCE 4 PORTAIL C+ FRANCE 3 8 MONT BLANC BBC WORLD NEWS 14 157 435 480 542 - TVA intracommunautaire FR 935 252 547 36 - Réalisation : Idéographic (19285) - Document À LA DEMANDE BASSE-NORMANDIE 6 17 CSTAR 158 À LA UNE CANAL 436 FRANCE 3 BOURGOGNE 481 ILTV 543 FRANCE 24 ENG 20 TF1 SÉRIES-FILMS 160 PARAMOUNT CHANNEL 437 FRANCE 3 BRETAGNE 482 ASTV 544 CNBC EUROPE 6TER PARAMOUNT DECALE FRANCE 3 CENTRE BFM GRAND LILLE BLOOMBERG 22 161 438 483 545 FRANCE 3 23 RMC STORY -

Generalistes 1. TF1 HD 2. M6 HD 3. Canal+ HD 4. Canal+ Decale

01 – FR – Generalistes 19. Serie Club HD 8. Nickelodeon Junior 1. TF1 HD 20. RTL9 9. Piwi+ HD 2. M6 HD 21. 13 Eme Rue HD 10. Nick4Teens 3. Canal+ HD 22. SyFy HD 11. Boing HD 4. Canal+ Decale HD 23. NT1 12. Canal J HD 5. France 2 HD 03 – FR – Sport 13. Boomerang HD 6. France 3 HD 1. Canal+ Sport HD 14. Manga 7. France 4 2. BEIN Sport 1 FR HD 15. GameOne 8. France 5 HD 3. BEIN Sport 2 FR HD 16. Cartoon Network HD 9. France O HD 4. BEIN Sport 3 FR HD 17. Disney Cinema 10. 6ter HD 5. SFR Sport 1 HD TEST 06 – FR – Infos - News 11. HD1 6. SFR Sport 2 HD 1. Euro News FR 12. Numero 23 HD 7. SFR Sport 3 HD 2. iTele HD 13. Cherie 25 HD 8. Foot+ 24h 3. FRANCE 24 FR 14. ARTE HD 9. GOLF+ HD 4. BFM TV 15. TV5 Monde 10. Infosport+ HD 5. LCI HD 16. W9 HD 11. Eurosport+ HD 06-1 – FR – Decalage +6 TS 17. D8 HD 12. Eurosport HD 1. TF1 HD +6 18. D17 HD 13. Eurosport 2 HD 2. M6 HD +6 19. Paris Premiere HD 14. Ma Chaine Sport HD 3. Canal+ HD +6 20. Comedie+ HD 15. OM TV HD 4. France 2 HD +6 21. E! Entertainment 16. BEIN Sport Max 5 HD 5. France 3 HD +6 22. June HD 17. BEIN Sport Max 6 HD 6. France 4 +6 23. Teva HD 18. BEIN Sport Max 7 HD 7. -

Red-Ftth-Dsl-Guidetv.Pdf

Chaînes disponibles avec l'option TV RED ou disponibles dans l'offre RED Box JUSQU'A 35 CHAINES DISPONIBLES 1 TF1 HD 14 France 4 28 et 46 i24 News 2 France 2 HD 15 BFM TV 31 et 96 BFM Business 3 France 3 Régions HD 16 Cnews 39 et 280 BFM Paris 4 CANAL + en clair HD* 17 Cstar 75 TF1+1 5 France 5 HD 18 Gulli 76 TMC+1 6 M6 HD 20 TF1 Séries-Films 281 et 479 BFM Lyon 7 Arte HD 21 L'equipe 282 et 483 BFM Grand Lille 8 C8 HD 22 6ter 284 et 516 BFM Marseille Provence 9 W9 HD 23 RMC Story 285 et 518 BFM Nice Cote d'Azur 10 TMC 24 et 172 RMC Decouverte 286 et 517 BFM Toulon Var 11 TFX 25 Cherie 25 547 i24 News Anglais 12 NRJ12 26 LCI 555 i24 News Arabe 13 LCP 27 France Info Ceci est un message du Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel et du Ministère de la Santé : Regarder la télévision, y compris les chaînes présentées comme spécifiquement conçues pour les enfants de moins de trois ans, peut entraîner chez certains des troubles du développement tels que passivité, retard du langage, agitation, troubles du sommeil, troubles de la concentration et dépendance aux écrans. * Disponible uniquement avec l'option TV RED. Non disponible dans les chaînes incluses à l'offre RED Box. Chaines disponibles avec l'option TV RED PLUS ou le bouquet TV RED Plus JUSQU’À 100 CHAINES - CHAINES SUPPLEMENTAIRES AUX 35 CHAINES CI-DESSUS 32 01TV 212 Nickelodeon Teen HD 713 Armenia 1 47 France 24 234 Lucky Jack 731 RTR Planeta 48 Euronews 235 Ginx 738 TV Romania International 56 MTV HD 250 MTV Hits HD 742 Canal Algerie 60 Game One 254 M6 Music 746 Beur TV 61 Game One +1 HD