Virtus 2017 Binnenwerk.Indb 173 13-02-18 12:38 Virtus 24 | 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declining Homogamy of Austrian-German Nobility in the 20Th Century? a Comparison with the Dutch Nobility Dronkers, Jaap

www.ssoar.info Declining homogamy of Austrian-German nobility in the 20th century? A comparison with the Dutch nobility Dronkers, Jaap Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Dronkers, J. (2008). Declining homogamy of Austrian-German nobility in the 20th century? A comparison with the Dutch nobility. Historical Social Research, 33(2), 262-284. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.33.2008.2.262-284 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-191342 Declining Homogamy of Austrian-German Nobility in the 20th Century? A Comparison with the Dutch Nobility Jaap Dronkers ∗ Abstract: Has the Austrian-German nobility had the same high degree of no- ble homogamy during the 20th century as the Dutch nobility? Noble homog- amy among the Dutch nobility was one of the two main reasons for their ‘con- stant noble advantage’ in obtaining elite positions during the 20th century. The Dutch on the one hand and the Austrian-German nobility on the other can be seen as two extreme cases within the European nobility. The Dutch nobility seems to have had a lower degree of noble homogamy during the 20th century than the Austrian-German nobility. -

The Tightrope Walk of the Dutch Nobility

BETWEEN CONFORMING AND CONSERVING: THE TIGHTROPE WALK OF THE DUTCH NOBILITY Nina IJdens A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science July 2017 Department of Sociology University of Amsterdam Supervisor: Dr. Kobe de Keere Second reader: Dr. Alex van Venrooij BETWEEN CONFORMING AND CONSERVING 1 Abstract Research has shown that the Dutch nobility has adapted to modernisation processes and continues to disproportionately occupy elite positions. This thesis builds on these findings by raising the question: (1) How does the Dutch nobility aim to maintain its high status position? Secondly, this thesis builds on a growing concern within studies of social stratification on how elite positions are legitimated in a highly unequal context. It investigates the nobility’s legitimation by raising the further questions (2a) How does the nobility legitimate itself through its organisations?; and (2b) How do members of the nobility justify their manifestation as a separate social group? The dataset consists of two sources: fourteen nobility organisations’ websites and fifty-two newspaper articles from 1990 until today, that contain interviews with members of the nobility. This research conducts a qualitative content analysis of these sources, looking for discursive hints of position maintenance, organisational legitimation, and justification. It shows that nobles maintain exclusive social networks that organise interesting networking opportunities; that the nobility copied modern organisational structures through which it could manifest itself as a social group; and that nobles justify their networks by appealing to a collective identity with a right to self-realisation. Moreover, the interviewees constantly both assert and downplay differences between themselves and the general public. -

Above the Clouds Page 1

Above the Clouds Page 1 Above the Clouds Status Culture of the Modern Japanese Nobility Takie Sugiyama Lebra University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Above the Clouds Page 2 University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1993 by The Regents of the University of California First Paperback Printing 1995 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lebra, Takie Sugiyama, 1930- Above the clouds : status culture of the modern Japanese nobility / Takie Sugiyama Lebra. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-07602-8 1. Japan—Social life and customs—20th century. 2. Nobility— Japan. L Title. DS822.3.L42 1992 306.4’0952—dc20 91-28488 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Above the Clouds Page 3 To the memory of William P. Lebra Above the Clouds Page 4 Contents List of Tables List of Illustrations Orthographic Note on Japanese Words Acknowledgments 1. Studying the Aristocracy: Why, What, and How? 2. Creating the Modern Nobility: The Historical Legacy 3. Ancestors: Constructing Inherited Charisma 4. Successors: Immortalizing the Ancestors 5. Life-Style: Markers of Status and Hierarchy 6. Marriage: Realignment of Women and Men 7. Socialization: Acquisition and Transmission of Status Culture 8. Status Careers: Privilege and Liability 9. Conclusion Epilogue: The End of Showa Notes Glossary References Above the Clouds Page 5 Tables 1. -

The Wealth of the Richest Inequality and the Nobility in Sweden, 1750–1900 Bengtsson, Erik; Missiaia, Anna; Olsson, Mats; Svensson, Patrick

The Wealth of the Richest Inequality and the Nobility in Sweden, 1750–1900 Bengtsson, Erik; Missiaia, Anna; Olsson, Mats; Svensson, Patrick Published: 2017-01-01 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bengtsson, E., Missiaia, A., Olsson, M., & Svensson, P. (2017). The Wealth of the Richest: Inequality and the Nobility in Sweden, 1750–1900. (Lund Papers in Economic History: General Issues; No. 161). Lund: Department of Economic History, Lund University. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private LUND UNIVERSITY study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? PO Box 117 Take down policy 221 00 Lund If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove +46 46-222 00 00 access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Lund Papers in Economic History No. 161, 2017 General Issues The Wealth of the Richest: Inequality and the Nobility in Sweden, 1750–1900 Erik Bengtsson, Anna Missiaia, Mats Olsson & Patrick Svensson DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY, LUND UNIVERSITY Lund Papers in Economic History ISRN LUSADG-SAEH-P--17/161--SE+28 © The author(s), 2017 Orders of printed single back issues (no. -

Microstructures of Global Trade – Porcelain Acquisitions Through

Microstructures of global trade Porcelain acquisitions through private networks for Augustus the Strong U2 | Microstructures of global trade Microstructures of global trade Porcelain acquisitions through private networks for Augustus the Strong Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Porzellansammlung, Ruth Sonja Simonis IMPRESSUM This publication by the Porzellansammlung results from the research project “Microstructures of Global Trade. The East Asian Porcelain in the Collection of August the Strong in the Context of the Inventories from the 18th Century“, sponsored by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Editor Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Porzellansammlung, Ruth Sonja Simonis PSF 120 551, 01006 Dresden, Tel.: (0351) 4914 2000 E-mail: [email protected] www.skd.museum Author Ruth Sonja Simonis Copy editors Mark Poysden, Stefan Osadzinski Transcriptions Sabine Wilde Graphic design, typesetting and repro Yasmin Karim www.yasminkarim.de Published at arthistoricum.net, Heidelberg University Library 2020. Cover illustration: Augustus II the Strong by Louis de Silvestre, 1718. Oil on canvas, H. 252.2 cm, W. 171.7 cm. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Gal.-Nr. 3943, photo: Jürgen Karpinski. Text © 2020, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden and the author. The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic information can be found on the Internet website: http://dnb.dnb.de. This book and its cover are published under the Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. The electronic open access version of this work is permanently available on https://www.arthistoricum.net URN: urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-ahn-artbook-499-0 DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.499 ISBN: 978-3-947449-64-4 (Softcover) ISBN: 978-3-947449-63-7 (PDF) ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ruth Sonja Simonis studied Japanese Studies and East Asian Art History at Freie Universität Berlin. -

Women and Public Life in Early Meiji Japan

Women and Public Life in Early Meiji Japan Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies Number 71 Center for Japanese Studies The University of Michigan Women and Public Life in Early Meiji Japan: The Development of the Feminist Movement MARA PATESSIO Center for Japanese Studies The University of Michigan Ann Arbor 2011 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 2011 by The Regents of the University of Michigan Published by the Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan 1007 E. Huron St. Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1690 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patessio, Mara, 1975- Women and public life in early Meiji Japan : the development of the feminist movement / Mara Patessio. p. cm. — (Michigan monograph series in Japanese studies ; no. 71) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-929280-66-7 (hbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-929280-67-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Women—Japan—History—19th century. 2. Women—Japan—History— 20th century. 3. Feminism—Japan—History—19th century. 4. Feminism— Japan—History—20th century. 5. Japan—History—1868- I. Title. II. Series. HQ1762.P38 2011 305.48-8956009034—dc22 2010050270 This book was set in Times New Roman. Kanji was set in Hiragino Mincho Pro. This publication meets the ANSI/NISO Standards for Permanence of Paper for Publications and Documents in Libraries and Archives (Z39.48-1992). Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-92-928066-7 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-92-928067-4 -

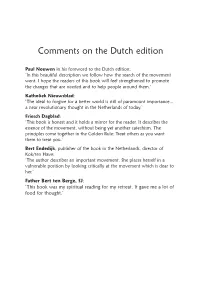

Comments on the Dutch Edition

Comments on the Dutch edition Paul Nouwen in his foreword to the Dutch edition: ‘In this beautiful description we follow how the search of the movement went. I hope the readers of this book will feel strengthened to promote the changes that are needed and to help people around them.’ Katholiek Nieuwsblad: ‘The ideal to forgive for a better world is still of paramount importance... a near revolutionary thought in the Netherlands of today.’ Friesch Dagblad: ‘This book is honest and it holds a mirror for the reader. It describes the essence of the movement, without being yet another catechism. The principles come together in the Golden Rule: Treat others as you want them to treat you.’ Bert Endedijk, publisher of the book in the Netherlands, director of Kok/ten Have: ‘The author describes an important movement. She places herself in a vulnerable position by looking critically at the movement which is dear to her.’ Father Bert ten Berge, SJ: ‘This book was my spiritual reading for my retreat. It gave me a lot of food for thought.’ Reaching for a new world Initiatives of Change seen through a Dutch window Hennie de Pous-de Jonge CAUX BOOKS First published in 2005 as Reiken naar een nieuwe wereld by Uitgeverij Kok – Kampen The Netherlands This English edition published 2009 by Caux Books Caux Books Rue de Panorama 1824 Caux Switzerland © Hennie de Pous-de Jonge 2009 ISBN 978-2-88037-520-1 Designed and typeset in 10.75pt Sabon by Blair Cummock Printed by Imprimerie Pot, 78 Av. des Communes-Réunies, 1212 Grand-Lancy, Switzerland Contents Preface -

The Art of Constitutional Legitimation: a Genealogy of Modern Japanese

Title Page The Art of Constitutional Legitimation: A Genealogy of Modern Japanese Political Thought by Tomonori Teraoka Bachelor of Law (LL.B.), Tohoku University, 2010 Master of International Affairs, The Pennsylvania State University, 2013 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2020 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Tomonori Teraoka It was defended on August 14, 2020 and approved by David L. Marshall, Associate Professor, Department of Communication Paul Elliott Johnson, Associate Professor, Department of Communication Dissertation Directors: Olga Kuchinskaya, Associate Professor, Department of Communication and Ricky Law, Associate Professor, Department of History (Carnegie Mellon University) ii Copyright © by Tomonori Teraoka 2020 iii The Art of Constitutional Legitimation: A Genealogy of Modern Japanese Political Thought Tomonori Teraoka, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2020 This dissertation examines rhetorical and historical issues of the two Japanese constitutions, the Meiji constitution (1889 − 1946) and the postwar constitution (1946 −). It examines a rhetorical issue of how persuasive narratives ground a constitution. It also examines a historical issue of modern Japan, that is to say, the re-emerging issue of whether or not, how, and how much Japan needed to domesticate foreign paradigms, a core of which was a modern constitution. The dissertation’s analysis of the two issues shows how the scholarly discourse in modern Japan (1868-) responded to the re-emerging issue of political/constitutional legitimacy across both the Meiji constitution and the postwar constitution. -

Download Download

30u089 Virtus 2010:30u089 Virtus 2009 08-02-2010 08:34 Pagina 227 KORTE BIJDRAGEN NOBILITY IN EUROPE DURING THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: MEMORIES, LOYALTIES AND ADVANTAGES IN CONTEXT Conference review The international conference on ‘Nobility in Europe during the twentieth Century’ was held at the European University Institute in Florence, 15-16 June 2009. The organizers of this expert meeting were Jaap Dronkers (EUI) and Yme Kuiper (University of Groningen); they profited greatly from the assistance of Nikolaj Bijleveld (University of Groningen) and Maureen Lechleitner (EUI). The attendees from various European universities presented a total of eight- een papers. Presenters offered a variety of approaches, ranging from history and anthropology to sociology, with the aim to thoroughly study and analyse the nobility in contemporary Europe. It is commonly held that the nobility lost its power and vanished from the world scene after bourgeois revolutions. Undoubtedly this belief is partly responsible for the fact that for decades the nobility has failed to arouse interest of social scientists. The present conference sought to fill in this gap, staging the twentieth century as well as the current nobility. Several conference papers dealt with strategies employed by the nobility to access econom- ic and other power resources. Nikolaj Bijleveld first of all presented his work on the renais- sance of the Dutch nobility that took place around 1900. In his paper, Bijleveld demonstrated how Dutch nobles at that point in time started to organise themselves in response to the upcom- ing bourgeoisie and consequently a possible downward mobility. Various anchor points of noble identity in the Netherlands, such as the Dutch Nobility Association, the Adelsboek, the Order of Saint John and the Order of Malta, were all founded within the twelve year period between 1899 and 1911. -

HANS DE VALK Distance and Attraction: Dutch Aristocracy and the Political Right Wing

HANS DE VALK Distance and Attraction: Dutch Aristocracy and the Political Right Wing in KARINA URBACH (ed.), European Aristocracies and the Radical Right 1918-1939 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 73–88 ISBN: 978 0 199 23173 7 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 5 Distance and Attraction: Dutch Aristocracy and the Political Right Wing HANS DE VALK To take as a topic the attitude of the Dutch nobility towards the extreme political right in the interwar period presupposes that this can be treated as a case in its own right. Some preliminary ques- tions, therefore, have to be answered. What was the status of the Dutch nobility in the early twentieth century? Did it possess any special social and political influence? Can it be treated as a sepa- rate part of the country's upper class? Thereafter, a brief survey of the confusing political landscape of the Dutch extreme right will be necessary to provide the background against which to place aristocratic commitment. -

Karatasli-Dissertation-2013

FINANCIAL EXPANSIONS, HEGEMONIC TRANSITIONS AND NATIONALISM: A LONGUE DURÉE ANALYSIS OF STATE-SEEKING NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS by Şahan Savaş KARATAŞLI A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October, 2013 © 2013 Şahan Savaş Karataşlı All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation provides a constructive criticism of theories that predict a decline in state-seeking nationalist movements in the 21st century, including the many theories that claim that the trajectory of nationalist movements is shaped like an inverted U-curve. Through a historical comparative analysis of state-seeking nationalist movements from 1000 AD to 2012, we show that these movements have been characterized by a cyclical pattern in the longue durée. More specifically, the incidence of state-seeking nationalist movements on a world-scale has tended to rise during periods of financial expansion and world-hegemonic crisis and has tended to decline during periods of material expansion and world-hegemonic consolidation. Thus, we expect to see a major resurgence of nationalist movements in the near future, the shape of which is contingent on how the current crisis of US hegemony unfolds. In addition to documenting this cyclical pattern in the prevalence of state-seeking nationalist movements, the study documents the evolution in the forms taken by these movements over time. Class composition and the predominant forms taken by the "nation" have changed from one world hegemony (systemic cycle of accumulation) to the next. The cyclical and evolutionary patterns can in turn be traced to the ways in which state-building strategies fluctuate over time and space between the use of "force" and the use of "consent", on the one hand, and the ways in which state-building strategies themselves have evolved (e.g., from the imposition of religious uniformity to the imposition of linguistic homogenization), on the other hand. -

Why and How Does the Dutch Nobility Retain Its Social Relevance?

133064-4 Virtus 2012_binnenwerk 21-03-13 15:41 Pagina 83 Why and how does the Dutch nobility retain its social relevance? Simon Unger and Jaap Dronkers* Introduction Modernization theory posits that contemporary Western societies are involved in a process of ever-increasing rationalization. This widely accepted theory is based on the assumption that traditional cultures gradually disappear and give way to a rationalized, characteristically bourgeois form of life. For instance, it has often been argued that gender differences and social inequalities have decreased, while social mobility in general has dramatically increased throughout the last two centuries. Similarly, it is regularly argued that class differences are leveled by our present-day capitalist, meritocratic culture. This process is certainly fostered by government-run welfare systems and a strengthening of the tertiary sector economy. The empirical evidence for this develop - ment can be easily discerned in society. For instance, the proletariat as a distinct social class has by and large disappeared, having been absorbed into a more loosely defined middle class. Can a complementary development be observed in so far as the upper classes are concerned? In line with modernization theory, it has been supposed that tradi - tional European elites, that is, the aristocracy and the nobility, have lost their position in the social hierarchy and have been socioeconomically integrated into the bourgeoisie. 1 In earlier studies, the Dutch nobility has been found to possess a strong advantage in achieving elite positions within the Dutch society, even though its legal status is remark - * The first author was a student at the University College of Maastricht University , and he wrote this article as an under - graduate research project.