Molecular Ecology of Social Behaviour: Analyses of Breeding Systems and Genetic Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sensory and Cognitive Adaptations to Social Living in Insect Societies Tom Wenseleersa,1 and Jelle S

COMMENTARY COMMENTARY Sensory and cognitive adaptations to social living in insect societies Tom Wenseleersa,1 and Jelle S. van Zwedena A key question in evolutionary biology is to explain the solitarily or form small annual colonies, depending upon causes and consequences of the so-called “major their environment (9). And one species, Lasioglossum transitions in evolution,” which resulted in the pro- marginatum, is even known to form large perennial euso- gressive evolution of cells, organisms, and animal so- cial colonies of over 400 workers (9). By comparing data cieties (1–3). Several studies, for example, have now from over 30 Halictine bees with contrasting levels of aimed to determine which suite of adaptive changes sociality, Wittwer et al. (7) now show that, as expected, occurred following the evolution of sociality in insects social sweat bee species invest more in sensorial machin- (4). In this context, a long-standing hypothesis is that ery linked to chemical communication, as measured by the evolution of the spectacular sociality seen in in- the density of their antennal sensillae, compared with sects, such as ants, bees, or wasps, should have gone species that secondarily reverted back to a solitary life- hand in hand with the evolution of more complex style. In fact, the same pattern even held for the socially chemical communication systems, to allow them to polymorphic species L. albipes if different populations coordinate their complex social behavior (5). Indeed, with contrasting levels of sociality were compared (Fig. whereas solitary insects are known to use pheromone 1, Inset). This finding suggests that the increased reliance signals mainly in the context of mate attraction and on chemical communication that comes with a social species-recognition, social insects use chemical sig- lifestyle indeed selects for fast, matching adaptations in nals in a wide variety of contexts: to communicate their sensory systems. -

Thysanoptera, Phlaeothripinae)

Zootaxa 4759 (3): 421–426 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4759.3.8 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F725F128-FCF3-4182-8E88-ECC01F881515 Two new monobasic thrips genera for a gall-inducing species and its kleptoparasite (Thysanoptera, Phlaeothripinae) LAURENCE A. MOUND & ALICE WELLS Australian National Insect Collection CSIRO, PO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601 [email protected] Abstract Drypetothrips korykis gen. et sp.n. is described as inducing leaf-margin galls on a small tree in Australia, Drypetes deplanchei [Putranjivaceae]. This thrips is similar in appearance to the smaller species of the genus Kladothrips that induce galls on Acacia species. The galls are invaded by a phytophagous kleptoparasitic thrips, Pharothrips hynnis gen. et sp.n., females of which have a forked plough-like structure protruding ventrally on the frons that is unique amongst Thysanoptera. Key words: autapomorphy, systematic relationships, leaf-margin galls, Australia Introduction The small tree, Drypetes deplanchei [Putranjivaceae], is widespread across northern Australia as far south as New- castle on the east coast. This tree is sometimes referred to as native holly, because the leaf margins can be sharply dentate, but these margins may also be almost smooth, and a species of thrips has been found inducing rolled margin galls on both leaf forms (Fig. 1). These galls and their thrips have been found at sites near Taree in coastal New South Wales, and also at Mt. Nebo near Brisbane in south-eastern Queensland. -

Early Behavioral and Molecular Events Leading to Caste Switching in the Ant Harpegnathos

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Early behavioral and molecular events leading to caste switching in the ant Harpegnathos Comzit Opachaloemphan,1,5 Giacomo Mancini,2,5 Nikos Konstantinides,2,5 Apurva Parikh,2 Jakub Mlejnek,2 Hua Yan,1,3,4 Danny Reinberg,1,3,6 and Claude Desplan2,6 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York 10016, USA; 2Department of Biology, New York University, New York, New York 10003, USA; 3Howard Hughes Medical Institute, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York 10016, USA Ant societies show a division of labor in which a queen is in charge of reproduction while nonreproductive workers maintain the colony. In Harpegnathos saltator, workers retain reproductive ability, inhibited by the queen phero- mones. Following the queen loss, the colony undergoes social unrest with an antennal dueling tournament. Most workers quickly abandon the tournament while a few workers continue the dueling for months and become gamergates (pseudoqueens). However, the temporal dynamics of the social behavior and molecular mechanisms underlining the caste transition and social dominance remain unclear. By tracking behaviors, we show that the gamergate fate is accurately determined 3 d after initiation of the tournament. To identify genetic factors responsible for this commitment, we compared transcriptomes of different tissues between dueling and nondueling workers. We found that juvenile hormone is globally repressed, whereas ecdysone biosynthesis in the ovary is increased in gamergates. We show that molecular changes in the brain serve as earliest caste predictors compared with other tissues. -

Experienced Individuals Influence the Thermoregulatory Fanning Behaviour

Animal Behaviour 142 (2018) 69e76 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Experienced individuals influence the thermoregulatory fanning behaviour in honey bee colonies * Rachael E. Kaspar a, , Chelsea N. Cook a, b, Michael D. Breed a a Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, The University of Colorado, Boulder, Boulder, CO, U.S.A. b Arizona State University, School of Life Sciences, Tempe, AZ, U.S.A. article info The survival of an animal society depends on how individual interactions influence group coordination. Article history: Interactions within a group determine coordinated responses to environmental changes. Individuals that Received 25 February 2018 are especially influential affect the behavioural responses of other group members. This is exemplified by Initial acceptance 4 April 2018 honey bee worker responses to increasing ambient temperatures by fanning their wings to circulate air Final acceptance 14 May 2018 through the hive. Groups of workers are more likely to fan than isolated workers, suggesting a coordi- Available online 10 July 2018 nated group response. But are some individuals more influential than others in this response? This study MS. number: A18-00153 tests the hypothesis that an individual influences other group members to perform thermoregulatory fanning behaviour in the western honey bee, Apis mellifera L. We show that groups of young nurse bees Keywords: placed with fanners are more likely to initiate fanning compared to groups of nurses without fanners. Apis mellifera L. Furthermore, we find that groups with young nurse bees have lower response thresholds than groups of fanning behaviour just fanners. -

The Risk‐Return Trade‐Off Between Solitary and Eusocial Reproduction

Ecology Letters, (2015) 18: 74–84 doi: 10.1111/ele.12392 LETTER The risk-return trade-off between solitary and eusocial reproduction Abstract Feng Fu,1* Sarah D. Kocher2 and Social insect colonies can be seen as a distinct form of biological organisation because they func- Martin A. Nowak2,3,4 tion as superorganisms. Understanding how natural selection acts on the emergence and mainte- nance of these colonies remains a major question in evolutionary biology and ecology. Here, we explore this by using multi-type branching processes to calculate the basic reproductive ratios and the extinction probabilities for solitary vs. eusocial reproductive strategies. We find that eusociali- ty, albeit being hugely successful once established, is generally less stable than solitary reproduc- tion unless large demographic advantages of eusociality arise for small colony sizes. We also demonstrate how such demographic constraints can be overcome by the presence of ecological niches that strongly favour eusociality. Our results characterise the risk-return trade-offs between solitary and eusocial reproduction, and help to explain why eusociality is taxonomically rare: eusociality is a high-risk, high-reward strategy, whereas solitary reproduction is more conserva- tive. Keywords Ecology and evolution, eusociality, evolutionary dynamics, mathematical biology, social insects, stochastic process. Ecology Letters (2015) 18: 74–84 There have been a number of attempts to identify some of INTRODUCTION the key ecological factors associated with the evolution of Eusocial behaviour occurs when individuals reduce their life- eusociality. Several precursors for the origins of eusociality time reproduction to help raise their siblings (Wilson 1971). have been proposed based on comparative analyses among Eusocial colonies comprise two castes: one or a few reproduc- social insect species – primarily the feeding and defense of off- tive individuals and a (mostly) non-reproductive, worker spring within a nest (Andersson 1984). -

Environmental Assessment of a Low-Energy Marine Geophysical Survey by the R/V Marcus G

Environmental Assessment of a Low-Energy Marine Geophysical Survey by the R/V Marcus G. Langseth in the Central Pacific Ocean, May 2012 Prepared for Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory 61 Route 9W, P.O. Box 1000 Palisades, NY 10964-8000 and National Science Foundation Division of Ocean Sciences 4201 Wilson Blvd., Suite 725 Arlington, VA 22230 by LGL Ltd., environmental research associates 22 Fisher St., POB 280 King City, Ont. L7B 1A6 30 November 2011 Revised 12 December 2011 LGL Report TA8098-1 Environmental Assessment for L-DEO’s Line Islands Seismic Survey, 2012 Page ii Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................... viii I. PURPOSE AND NEED .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. ALTERNATIVES INCLUDING PROPOSED ACTION ..................................................................................... 2 Proposed Action ................................................................................................................................. 2 (1) Project Objectives and Context .......................................................................................... 2 (2) Proposed Activities ............................................................................................................ -

Wedge-Shaped Beetles (Suggested Common Name) Ripiphorus Spp. (Insecta: Coleoptera: Ripiphoridae)1 David Owens, Ashley N

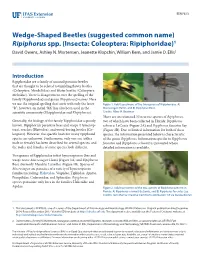

EENY613 Wedge-Shaped Beetles (suggested common name) Ripiphorus spp. (Insecta: Coleoptera: Ripiphoridae)1 David Owens, Ashley N. Mortensen, Jeanette Klopchin, William Kern, and Jamie D. Ellis2 Introduction Ripiphoridae are a family of unusual parasitic beetles that are thought to be related to tumbling flower beetles (Coleoptera: Mordellidae) and blister beetles (Coleoptera: Meloidae). There is disagreement over the spelling of the family (Ripiphoridae) and genus (Ripiphorus) names. Here we use the original spelling that starts with only the letter Figure 1. Adult specimens of the two genera of Ripiphoridae. A) “R”; however, an initial “Rh” has also been used in the Macrosiagon Hentz, and B) Ripiphorus Bosc. scientific community (Rhipiphoridae and Rhipiphorus). Credits: Allen M. Boatman There are an estimated 35 nearctic species of Ripiphorus, Generally, the biology of the family Ripiphoridae is poorly two of which have been collected in Florida: Ripiphorus known. Ripiphorids parasitize bees and wasps (Hymenop- schwarzi LeConte (Figure 2A) and Ripiphorus fasciatus Say tera), roaches (Blattodea), and wood-boring beetles (Co- (Figure 2B). Due to limited information for both of these leoptera). However, the specific hosts for many ripiphorid species, the information presented below is characteristic species are unknown. Furthermore, only one sex (either of the genus Ripiphorus. Information specific to Ripiphorus male or female) has been described for several species, and fasciatus and Ripiphorus schwarzi is presented where the males and females of some species look different. detailed information is available. Two genera of Ripiphoridae infest hymenopteran (bee and wasp) nests: Macrosiagon Hentz (Figure 1A) and Ripiphorus Bosc (formerly Myodites Latreille) (Figure 1B). Species of Macrosiagon are parasites of a variety of hymenopteran families including: Halictidae, Vespidae, Tiphiidae, Apidae, Pompilidae, Crabronidae, and Sphecidae. -

Comparative Methods Offer Powerful Insights Into Social Evolution in Bees Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton

Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton To cite this version: Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton. Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2014, 45 (3), pp.289-305. 10.1007/s13592-014-0268-3. hal- 01234748 HAL Id: hal-01234748 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01234748 Submitted on 27 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2014) 45:289–305 Review article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2014 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-014-0268-3 Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees 1 2 Sarah D. KOCHER , Robert J. PAXTON 1Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA 2Institute for Biology, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany Received 9 September 2013 – Revised 8 December 2013 – Accepted 2 January 2014 Abstract – Bees are excellent models for studying the evolution of sociality. While most species are solitary, many form social groups. The most complex form of social behavior, eusociality, has arisen independently four times within the bees. -

Insemination Controls the Reproductive Division of Labour in a Ponerine

Insemination Controls the Reproductive Division correlation between the occurrence of the two events, since the male data re- of Labour in a Ponerine Ant ported below indicate that the relation- ship is a causal one. Were ovarian ac- Chr. Peeters and R. Crewe tivity to be responsible for changes in Department of Zoology, University of the Witwatersrand, worker behaviour which lead to mat- Johannesburg, 2001, South Africa ing, we would expect to find unmated workers with developed ovaries. None The control of oviposition in insect co- frequent transfer of adults and brood have been found at any time of the lonies is fundamental to the structure between the nests along non-chemical year. Indeed we can state that the hap- of their social systems. In most ant so- trails. Workers are produced for most loid eggs which develop into males are cieties a distinct female caste performs of the year (with a hiatus in egg pro- laid by inseminated gamergates. Insem- the reproductive function, while the duction before winter) and this results ination also produced a change in the worker caste is sterile, or at the most in a nest population with individuals chemical composition of the mandibu- produces trophic or unfertilized (male) of various ages. lar gland pheromone of these ants and eggs. Winged males and virgin queens Single nests and nest complexes of in their behaviour. The mated ants re- are seasonally produced, and leave O. berthoudi were excavated at differ- mained inside their nests for the rest their nests on nuptial flights [1]. Thus ent times of the year, and a large sam- of their lives, except when they were a trend towards reproductive speciali- ple of ants from each unit was dis- carried from one nest to another. -

On the Frequency of Eusociality in Snapping Shrimps (Decapoda: Alpheidae), with Description of a Second Eusocial Species

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 62(3): 387–400, 1998 ON THE FREQUENCY OF EUSOCIALITY IN SNAPPING SHRIMPS (DECAPODA: ALPHEIDAE), WITH DESCRIPTION OF A SECOND EUSOCIAL SPECIES J. Emmett Duffy ABSTRACT Recently, the Caribbean snapping shrimp Synalpheus regalis was shown to be eusocial by the criteria historically used for honeybees, ants, and termites, i.e., colonies contain a single reproducing female and a large number of non-breeding “workers.” This finding prompted a reexamination of several previously puzzling reports of unusual population structures in other Synalpheus species. New collections, and observations made by stu- dents of this genus over the last century, suggest that several sponge-dwelling Synalpheus species similarly exhibit overlapping generations and monopolization of reproduction by a few individuals, and thus that these species may also be eusocial according to classical entomological criteria. The evidence for this conclusion includes reports of several Car- ibbean and Indo-Pacific species occurring in large aggregations of “juvenile” shrimp accompanied by few or no mature females. Here I describe one of these species as Synalpheus chacei. Like other members of the gambarelloides species group within this genus, S. chacei is an obligate inhabitant of living demosponges, and has been collected from at least seven host species in Caribbean Panama, Belize, and the Virgin Islands. Stomach contents comprised primarily detritus and diatoms, suggesting that S. chacei feeds on material inhaled in the host sponge’s feeding current. The new species is mor- phologically similar to S. bousfieldi, and is most reliably distinguished from it (and in- deed, apparently from all other species of Synalpheus) by a unique pair of longitudinal setal combs on the dactyl of the minor first chela. -

Social Dominance and Reproductive Differentiation Mediated By

© 2015. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | The Journal of Experimental Biology (2015) 218, 1091-1098 doi:10.1242/jeb.118414 RESEARCH ARTICLE Social dominance and reproductive differentiation mediated by dopaminergic signaling in a queenless ant Yasukazu Okada1,2,*, Ken Sasaki3, Satoshi Miyazaki2,4, Hiroyuki Shimoji2, Kazuki Tsuji5 and Toru Miura2 ABSTRACT (i.e. the unequal sharing of reproductive opportunity) is widespread In social Hymenoptera with no morphological caste, a dominant female in various animal taxa (Sherman et al., 1995; birds, Emlen and becomes an egg layer, whereas subordinates become sterile helpers. Wrege, 1992; mammals, Jarvis, 1981; Keane et al., 1994; Nievergelt The physiological mechanism that links dominance rank and fecundity et al., 2000). In extreme cases, it can result in the reproductive is an essential part of the emergence of sterile females, which reflects division of labor, such as in social insects and naked mole rats the primitive phase of eusociality. Recent studies suggest that (Wilson, 1971; Sherman et al., 1995; Reeve and Keller, 2001). brain biogenic amines are correlated with the ranks in dominance In highly eusocial insects (honeybees, most ants and termites), hierarchy. However, the actual causality between aminergic systems developmental differentiation of morphological caste is the basis of and phenotype (i.e. fecundity and aggressiveness) is largely unknown social organization (Wilson, 1971). By contrast, there are due to the pleiotropic functions of amines (e.g. age-dependent morphologically casteless social insects (some wasps, bumblebees polyethism) and the scarcity of manipulation experiments. To clarify and queenless ants) in which the dominance hierarchy plays a central the causality among dominance ranks, amine levels and phenotypes, role in division of labor. -

Model Organisms

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Nature Reviews Genetics | Published online 30 Aug 2017; doi:10.1038/nrg.2017.70 P. Morgan/Macmillan Publishers Limited Morgan/Macmillan P. its caste-specific RNA expression is conserved in other insect species with different social systems. In ants undergoing the worker–gamergate transition, high corazonin peptide levels promoted worker-specific behaviour and inhibited behaviours associated with progression to the MODEL ORGANISMS gamergate caste; as expected, short interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of the corazonin receptor (CrzR) gene New tools, new insights — had the opposite phenotypic effect. The researchers went on to identify the vitellogenin gene as a key regula- probing social behaviour in ants tory target of corazonin; its expres- sion is consistently downregulated Eusocial insects display complex strategy of Harpegnathos saltator to in response to increased corazonin social behaviours, but the underlying increase the number of reproducing levels, suggesting that corazonin and Until now, molecular mechanisms are largely ants to enable them to establish orco vitellogenin have opposing effects functional unknown. Now, a trio of papers in mutant lines. In the absence of a on caste identity. Consistent with genetic studies Cell decribe two genes (orco and queen, non-reproductive H. saltator this hypothesis, siRNA knockdown corazonin) that control social behav- workers can become ‘gamergates’, of vitellogenin gene expression pro- have not been iour in ants. Furthermore, two of which lay fertilized eggs. This caste moted worker-specific behaviours. possible in the studies describe the first mutant transition can be replicated in the lab Based on these observations, the ants lines in ants, which were generated by simply by isolating workers.