Reformation History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of the Roman Rite by Michael Davies

The Development of the Roman Rite By Michael Davies The Universe is the Catholic newspaper with the largest circulation in Britain. On 18 May 1979 its principal feature article was by one Hugh Lindsay, Bishop of Hexam and Newcastle. The Bishop's article was entitled "What Can the Church Change?" It was a petulant, petty, and singularly ill-informed attack upon Archbishop Lefebvre and Catholic traditionalists in general. It is not hard to understand why the Archbishop is far from popular with the English hierarchy, and with most hierarchies in the world for that matter. The Archbishop is behaving as a true shepherd, defending the flock from who would destroy it. He is a living reproach to the thousands of bishops who have behaved as hirelings since Vatican II. They not only allow enemies to enter the sheepfold but enjoy nothing more than a "meaningful dialogue" with them. The English Bishops are typical of hierarchies throughout the world. They allow catechetical programs in their schools which leave Catholic children ignorant of the basis of their faith or even teach a distorted version of that faith. When parents complain the Bishops spring to the defense of the heterodox catechists responsible for undermining the faith of the children. The English Bishops remain indifferent to liturgical abuse providing that it is initiated by Liberals. Pope Paul VI appealed to hierarchies throughout the world to uphold the practice of Communion on the tongue. Liberal clerics in England defied the Holy See and the reaction of the Bishops was to legalize the practice. The same process is now taking place with the practice of distributing Communion under both kinds at Sunday Masses. -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

Low Requiem Mass

REQUIEM LOW MASS FOR TWO SERVERS The Requiem Mass is very ancient in its origin, being the predecessor of the current Roman Rite (i.e., the so- called “Tridentine Rite”) of Mass before the majority of the gallicanizations1 of the Mass were introduced. And so, many ancient features, in the form of omissions from the normal customs of Low Mass, are observed2. A. Interwoven into the beautiful and spiritually consoling Requiem Rite is the liturgical principle, that all blessings are reserved for the deceased soul(s) for whose repose the Mass is being celebrated. This principle is put into action through the omission of these blessings: 1. Holy water is not taken before processing into the Sanctuary. 2. The sign of the Cross is not made at the beginning of the Introit3. 3. C does not kiss the praeconium4 of the Gospel after reading it5. 4. During the Offertory, the water is not blessed before being mixed with the wine in the chalice6. 5. The Last Blessing is not given. B. All solita oscula that the servers usually perform are omitted, namely: . When giving and receiving the biretta. When presenting and receiving the cruets at the Offertory. C. Also absent from the Requiem Mass are all Gloria Patris, namely during the Introit and the Lavabo. D. The Preparatory Prayers are said in an abbreviated form: . The entire of Psalm 42 (Judica me) is omitted; consequently the prayers begin with the sign of the Cross and then “Adjutorium nostrum…” is immediately said. After this, the remainder of the Preparatory Prayers are said as usual. -

Immaculate Conception Catholic Church † Mission of the Sacred Heart 865 Hatchell Lane (70726); P

Immaculate Conception Catholic Church † Mission of the Sacred Heart 865 Hatchell Lane (70726); P. O. Box 1609 Denham Springs, LA 70727 Phone (225) 665-5359 ◦ Fax (225) 665-4422 www.icc-msh.org ◦ [email protected] November 22, 2015 Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe Volume 38 ● Number 46 PASTORAL STAFF: Rev. Frank M. Uter. Pastor The Alpha The Rev. Amal Raj, I.M.S. Associate Pastor Paul Barnett. Parish Administrator and Beginning and Tammy Jackson. Assistant Parish Administrator Mike Chiappetta . Permanent Deacon The Omega The End Peter Schlette. .Permanent Deacon Rudy Stahl. Permanent Deacon MASS SCHEDULE Saturday Vigil. .4:00 p.m. Sundays . 7 a.m., 9 a.m., 9a.m. (MSH), 11 a.m. & 6 p.m. Monday-Wednesday-Thursday-Friday-8:30 a.m. Tuesday . .6:00 pm followed by Novena/Benediction Holy Days. As announced SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION Tuesday . 5:30-5:45 p.m. Friday . .8:00-8:20 a.m. Saturday . .2:45-3:45 p.m. Other times as announced or by appointment. BAPTISMS: Notify Parish Office during pregnancy. Instruction for parents and godparents is required. MARRIAGE: Contact the Parish Office at least six months before desired date. Come Join Us as We Give Thanks to God PRAYER LINE: (confidential ministry) Contact Ms. Pat Pastor at 664-1097. Thanksgiving Mass CelebraƟons CARE OF THE SICK: Emergency calls Wednesday, November 25 at 6 p.m. answered immediately. Home visitation for the (No 8:30 a.m. Mass) sick and shut-in weekly and upon request. Hospital visits weekly and upon request. -

13 September 2020 the True Cross in the Following Manner

13 September 2020 The True Cross in the following manner. He caused a lady of rank, who Roodmas (from Old English rood “rod” or “cross,” had been long suffering from disease, to be touched by and mas, Mass; similar to the etymology of each of the crosses, with earnest prayer, and thus Christmas) was the celebration of the Feast of the discerned the virtue residing in that of the Saviour. Cross observed on May 3 in some Christian churches For the instant this cross was brought near the lady, it and rites, particularly the historical Gallican Rite of expelled the sore disease, and made her whole. the Catholic Church. It commemorated the finding Helena took a portion of the cross back to Rome, by Saint Helena of the True Cross in Jerusalem in 355. where she had it enshrined in the chapel of her palace A separate feast of the Triumph of the Cross was (now the Basilica of the “Holy Cross in Jerusalem”). celebrated on September 14, the anniversary of the The rest of the True Cross remained in Jerusalem, in a dedication of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. After chapel attached to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. the Gallican and Latin Rites were combined, the Over the centuries pieces of the Cross were distributed western Church observed individually the Finding of the as relics in both the East and the West. Many were Holy Cross on May 3 and the Triumph of the Cross on captured and lost amidst the wars of possession fought September 14. -

The Liturgical Year

22 The Liturgical Year Holy Church celebrates the saving work of Christ on prescribed days in the course of the year with sacred remembrance. Each week, on the day called the Lord’s Day, she commemorates the Resurrection of the Lord, which she also celebrates once a year in the great Paschal Solemnity, together with his blessed Passion. In fact, throughout the course of the year the Church unfolds the entire mystery of Christ and observes the birthdays of the Saints. Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year and the General Roman Calendar [UNLYC], no. 1 LITURGICAL DAYS 1. Each day is made holy through the celebration of the Liturgy by the People of God. 2. This happens especially through the Eucharistic Sacrifice and the Divine Office. 3. The observance of Sunday and Solemnities begins with the evening of the preceding day. 4. All other liturgical days run from midnight to midnight. 5. Sunday is ranked the first holy day of all, the primordial feast day. 6. Solemnities are principal days in the calendar. Each begins with Evening Prayer I on the preceding day. Some have their own vigil Mass for use on the preceding evening: • The Nativity of the Lord (Christmas), 25 December; • The Epiphany of the Lord, Sunday between January 2 and 8 (USA); • The Ascension of the Lord, moved to Sunday in the Province of Chicago; • Nativity of St. John the Baptist, 24 June; • Sts. Peter and Paul, Apostles, 29 June; • Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, 15 August; • and Pentecost Sunday, Extended form and Simple form. • The Easter Vigil in the Holy Night follows its own rules. -

The Resurrection of Jesus in Eastern Christian Iconography.” Please Join Me in Welcoming John Dominic Crossan

Presidential Address by John DoMinic Crossan President of the Society of Biblical Literature 2012 Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature November 17, 2012 Chicago, Illinois Introduction given by Carol L. Meyers Vice President, Society of Biblical Literature If you’ve read the announcement of this session in the SBL program book—and I suspect many of you have, or else you wouldn’t have decided to come to this lecture room at this time—you’ve read the biographical summary providing the basic facts about SBL president John Dominic Crossan. And even if you haven’t read that summary, you still probably know many of those basic facts. You are well aware that he is arguably the world’s foremost historical-Jesus scholar. (In fact, a local taxi driver, in finding out that the John Dominic Crossan was a passenger in his cab, exclaimed that he wanted to put a plaque there to show where the famous Crossan had sat during the cab ride!) You probably also know that he is a native of Ireland, that he was educated in both Ireland (where he earned his doctorate of divinity at the theological seminary of the national University of Ireland in Kildare) and in the United States, and that he also did postdoctoral work in Rome at the Pontifical Biblical Institute and in Jerusalem at the l’École biblique et archéologique française. You may also know that he was an ordained priest for many years, that he left the priesthood in 1969, and that he was on the faculty of DePaul University here in Chicago until he became professor emeritus in 1995. -

LITURGICAL DEVELOPMENT of the MASS-Ill

LITURGICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE MASS-Ill ALEXIUS SIMONES, O.P. FTER the Credo, the catechumens having been dismissed, the root of the service-the repetition of what Our Lord did at the Last Supper-begins. Our Lord took bread and · wine. So bread and wine must first be brought to the cele brant and placed before him on the altar. St. Justin says that "bread and a cup of wine are brought to the president of the brethren." Originally at this point the people brought up bread and wine which were received by the deacon and placed on the credence table. How ever, in the Eastern rites and in the Gallican rite a later practice of preparing the bread and wine before the beginning of the Mass grew up. Rome alone kept the original practice of offering them at this point, when they are about to be consecrated. In the Middle Ages, as the public presentation of the gifts by the people had disappeared, there seemed to be a void. This interval was fi lled up by our present offertory prayers. But even before the disappearance of this public presentation, the choir sang merely to fill up the time while the sil ent action of offering the gifts proceeded. The offertory chant is of great antiquity. Like the Introit and Communion chants, this chant was always an entire psalm in the early ages. By the time of the first Roman Ordo, the psalm was re duced to an antiphon with one or two verses of the psalm. In the Gregorian Antiphonary it is still the same. -

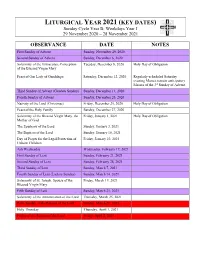

LITURGICAL YEAR 2021 (KEY DATES) Sunday Cycle Year B; Weekdays Year I 29 November 2020 – 28 November 2021

LITURGICAL YEAR 2021 (KEY DATES) Sunday Cycle Year B; Weekdays Year I 29 November 2020 – 28 November 2021 OBSERVANCE DATE NOTES First Sunday of Advent Sunday, November 29, 2020 Second Sunday of Advent Sunday, December 6, 2020 Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception Tuesday, December 8, 2020 Holy Day of Obligation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe Saturday, December 12, 2020 Regularly-scheduled Saturday evening Masses remain anticipatory Masses of the 3rd Sunday of Advent. Third Sunday of Advent (Gaudete Sunday) Sunday, December 13, 2020 Fourth Sunday of Advent Sunday, December 20, 2020 Nativity of the Lord (Christmas) Friday, December 25, 2020 Holy Day of Obligation Feast of the Holy Family Sunday, December 27, 2020 Solemnity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Friday, January 1, 2021 Holy Day of Obligation Mother of God The Epiphany of the Lord Sunday, January 3, 2021 The Baptism of the Lord Sunday, January 10, 2021 Day of Prayer for the Legal Protection of Friday, January 22, 2021 Unborn Children Ash Wednesday Wednesday, February 17, 2021 First Sunday of Lent Sunday, February 21, 2021 Second Sunday of Lent Sunday, February 28, 2021 Third Sunday of Lent Sunday, March 7, 2021 Fourth Sunday of Lent (Laetare Sunday) Sunday, March 14, 2021 Solemnity of St. Joseph, Spouse of the Friday, March 19, 2021 Blessed Virgin Mary Fifth Sunday of Lent Sunday, March 21, 2021 Solemnity of the Annunciation of the Lord Thursday, March 25, 2021 Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord Sunday, March 28, 2021 Holy Thursday Thursday, April 1, 2021 Friday of the Passion of the Lord Friday, April 2, 2021 Holy Saturday Saturday, April 3, 2021 Sunset is 8:08 p.m. -

Issue 24 - September 2019

ARCHDIOCESE OF PORTLAND IN OREGON Divine Worship Newsletter Polish Chapel, National Shrine, DC ISSUE 24 - SEPTEMBER 2019 Welcome to the twenty fourth Monthly Newsletter of the Office of Divine Worship of the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon. We hope to provide news with regard to liturgical topics and events of interest to those in the Archdiocese who have a pastoral role that involves the Sacred Liturgy. The hope is that the priests of the Archdiocese will take a glance at this newsletter and share it with those in their parishes that are involved or interested in the Sacred Liturgy. This Newsletter is now available through Apple Books and always available in pdf format on the Archdiocesan website. It will also be included in the weekly priests’ mailing. If you would like to be emailed a copy of this newsletter as soon as it is published please send your email address to Anne Marie Van Dyke at [email protected]. Just put DWNL in the subject field and we will add you to the mailing list. All past issues of the DWNL are available on the Divine Worship Webpage and from Apple Books. An index of all the articles in past issues is also available on our webpage. The answer to last month’s competition was: The Church of the Gesu, Rome - the first correct answer was submitted by John Miller of Our Lady of Loreto Parish in Foxfield, CO. If you have a topic that you would like to see explained or addressed in this newsletter please feel free to email this office and we will try to answer your questions and address topics that interest you and others who are concerned with Sacred Liturgy in the Archdiocese. -

SHORT HISTORY of the ROMAN MASS by Michael Davies

SHORT HISTORY OF THE ROMAN MASS by Michael Davies Table of Contents: Gradual Development of Ceremonies The End of Persecutions The Gallican Rite The Origins of the Roman Rite and its Liturgical Books The Canon of the Mass Dates from the 4th Century The Reform of St. Gregory the Great Eastern and Gallican Additions to the Roman Rite A Sacred Heritage Since the 6th Century The Reform of Pope St. Pius V Not a New Mass Revisions after 1570 Our Ancient Liturgical Heritage GRADUAL DEVELOPMENT OF CEREMONIES Although there was considerable liturgical uniformity in the first two centuries there was not absolute uniformity. Liturgical books were certainly being used by the middle of the 4th century, and possibly before the end of the third, but the earliest surviving texts date from the seventh century, and musical notation was not used in the west until the ninth century when the melodies of Gregorian chant were codified. The only book known with certainty to have been used until the fourth century was the Bible from which the lessons were read. Psalms and the Lord's Prayer were known by heart, otherwise the prayers were extempore. There was little that could be described as ceremonial in the sense that we use the term today. Things were done as they were done for some practical purpose. The lessons were read in a loud voice from a convenient place where they could be heard, and bread and wine were brought to the altar at the appropriate moment. Everything would evidently have been done with the greatest possible reverence, and gradually and naturally signs of respect emerged, and became established customs, in other words liturgical actions became ritualized. -

St. Ambrose and the Architecture of the Churches of Northern Italy : Ecclesiastical Architecture As a Function of Liturgy

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2008 St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy. Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider 1948- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Schneider, Sylvia Crenshaw 1948-, "St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1275. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1275 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B.A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2008 Copyright 2008 by Sylvia A. Schneider All rights reserved ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B. A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Approved on November 22, 2008 By the following Thesis Committee: ____________________________________________ Dr.