University of California at Berkeley College of Engineering Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M32R Debugger and Trace

M32R Debugger and Trace TRACE32 Online Help TRACE32 Directory TRACE32 Index TRACE32 Documents ...................................................................................................................... ICD In-Circuit Debugger ................................................................................................................ Processor Architecture Manuals .............................................................................................. M32R ......................................................................................................................................... M32R Debugger and Trace .................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 4 Brief Overview of Documents for New Users 4 Warning .............................................................................................................................. 5 Quick Start ......................................................................................................................... 6 Troubleshooting ................................................................................................................ 9 SYStem.Up Errors 9 Memory Access Errors 9 FAQ ..................................................................................................................................... 9 CPU specific SYStem Settings and Restrictions .......................................................... -

Mac OS 8 Update

K Service Source Mac OS 8 Update Known problems, Internet Access, and Installation Mac OS 8 Update Document Contents - 1 Document Contents • Introduction • About Mac OS 8 • About Internet Access What To Do First Additional Software Auto-Dial and Auto-Disconnect Settings TCP/IP Connection Options and Internet Access Length of Configuration Names Modem Scripts & Password Length Proxies and Other Internet Config Settings Web Browser Issues Troubleshooting • About Mac OS Runtime for Java Version 1.0.2 • About Mac OS Personal Web Sharing • Installing Mac OS 8 • Upgrading Workgroup Server 9650 & 7350 Software Mac OS 8 Update Introduction - 2 Introduction Mac OS 8 is the most significant update to the Macintosh operating system since 1984. The updated system gives users PowerPC-native multitasking, an efficient desktop with new pop-up windows and spring-loaded folders, and a fully integrated suite of Internet services. This document provides information about Mac OS 8 that supplements the information in the Mac OS installation manual. For a detailed description of Mac OS 8, useful tips for using the system, troubleshooting, late-breaking news, and links for online technical support, visit the Mac OS Info Center at http://ip.apple.com/infocenter. Or browse the Mac OS 8 topic in the Apple Technical Library at http:// tilsp1.info.apple.com. Mac OS 8 Update About Mac OS 8 - 3 About Mac OS 8 Read this section for information about known problems with the Mac OS 8 update and possible solutions. Known Problems and Compatibility Issues Apple Language Kits and Mac OS 8 Apple's Language Kits require an updater for full functionality with this version of the Mac OS. -

PRE LIM INARY KDII-D Processor Manual (PDP-Ll/04)

PRE LIM I N A R Y KDII-D Processor Manual (PDP-ll/04) The information in this document is subject to change without notice and should not be construed as a commitment by Digital Equipment Corporation. Digital Equipment Corporation assumes no responsibility for any errors that may appear in this manual. Copyright C 1975 by Digital Equipment Corporation Written by PDP-II Engineering PREFACE OVE~ALt DESCRIPTION 3 8 0 INsT~UCTION SET 3~1 Introduction 1~2 Addressing ModIs 3.3 Instruction Timing l@4 In~truet1on Dtlcriptlonl le!5 Dlffer~ncei a,tween KOlle and KOllS ]0 6 Programming Diftereneel B~twlen pepita ).7 SUI L~tency Tim@1 CPu OPERlTING 5PECIFICATID~S 5 e 0 DETAILED HARDWARE DESC~ltTION 5.1 IntrOduction 5 m2 Data path Circuitry 5.2g1 General D~serlpt1on 5.2,,2 ALU 5,2 .. 3 Scratch Pad Mtmory 5.2,.3.1 Scratch P~d Circuitry 5.2.3.2 SCrateh P~d Addr~11 MUltlplex.r 5.2.3.3 SCrateh Pad Regilter 5 0 2 .. 4 B J:H'!qilil ter 5.2 .. 4.1 B ReQister CircuItry 5.2 .. 4.2 8 L~G MUltl~lex@r 5,2.5 AMUX 5.2.6 Pfoeellof statuI Word (PSW) 5.3 Con<Htion COd@i 5.3.1 G~neral De~erl~tlon 5.3.2 Carry and overflow Decode 5.3.3 Ayte Multiplexing 5.4 UNIBUS Addf@$5 and Data Interfaces S.4 g 1 U~IBUS Dr1v~rl and ~lee1Vtrl 5.4@2 Bus Addr~s~ Generation 5 8 4111 Internal Addrf$$ D@coder 5 0 4,.4 Bus Data Line Interface S.5 Instruet10n DeCoding 5.5,,1 General De~er1pt1nn 5;5.2 Instruction Re91lt~r 5.5,,3 Instruetlon Decoder 5.5.3 0 1 Doubl~ O~erand InltrYetions 5.5.3.2 Single Operand Inltruetlons 5,5.3.3 Branch In$truetionl 5 8 5.3 6 4 Op~rate rn~truet1ons 5.6 Auil11ary ALU Control 5.6.1 G~ntral Delcrlptlon 5.6.2 COntrol Circuitry 5.6.2.1 Double Op@rand Instructions 5.6.2.2 Singl@ nDef~nd Instruet10ns PaQe 3 5.7 Data Transfer Control 5,7,1 General Descr1ption 5,7,2 Control CIrcuItry 5,7,2,1 Procelsor Cloek Inhibit 5,7,2.2 UNIBUS Synchronization 5,7.2,3 BUs Control 5.7,2.4 MSyN/SSYN Timeout 5,7.2.5 Bus Error. -

Processes, System Calls and More

Processes • A process is an instance of a program running • Modern OSes run multiple processes simultaneously • Very early OSes only ran one process at a time • Examples (can all run simultaneously): - emacs – text editor - firefox – web browser • Non-examples (implemented as one process): - Multiple firefox windows or emacs frames (still one process) • Why processes? - Simplicity of programming - Speed: Higher throughput, lower latency 1 / 43 A process’s view of the world • Each process has own view of machine - Its own address space - Its own open files - Its own virtual CPU (through preemptive multitasking) • *(char *)0xc000 dierent in P1 & P2 • Simplifies programming model - gcc does not care that firefox is running • Sometimes want interaction between processes - Simplest is through files: emacs edits file, gcc compiles it - More complicated: Shell/command, Window manager/app. 2 / 43 Outline 1 Application/Kernel Interface 2 User view of processes 3 Kernel view of processes 3 / 43 System Calls • Systems calls are the interface between processes and the kernel • A process invokes a system call to request operating system services • fork(), waitpid(), open(), close() • Note: Signals are another common mechanism to allow the kernel to notify the application of an important event (e.g., Ctrl-C) - Signals are like interrupts/exceptions for application code 4 / 43 System Call Soware Stack Application 1 5 Syscall Library unprivileged code 4 2 privileged 3 code Kernel 5 / 43 Kernel Privilege • Hardware provides two or more privilege levels (or protection rings) • Kernel code runs at a higher privilege level than applications • Typically called Kernel Mode vs. User Mode • Code running in kernel mode gains access to certain CPU features - Accessing restricted features (e.g. -

NI Vxipc-486 500 Series Lynxos Manual

Full-service, independent repair center -~ ARTISAN® with experienced engineers and technicians on staff. TECHNOLOGY GROUP ~I We buy your excess, underutilized, and idle equipment along with credit for buybacks and trade-ins. Custom engineering Your definitive source so your equipment works exactly as you specify. for quality pre-owned • Critical and expedited services • Leasing / Rentals/ Demos equipment. • In stock/ Ready-to-ship • !TAR-certified secure asset solutions Expert team I Trust guarantee I 100% satisfaction Artisan Technology Group (217) 352-9330 | [email protected] | artisantg.com All trademarks, brand names, and brands appearing herein are the property o f their respective owners. Find the National Instruments VXIpc-486 Model 566 at our website: Click HERE Getting Started with Your NI-VXI™ Software for the VXIpc™-486 Model 500 Series and LynxOS bus September 1995 Edition Part Number 321006A-01 © Copyright 1995 National Instruments Corporation. All Rights Reserved. National Instruments Corporate Headquarters 6504 Bridge Point Parkway Austin, TX 78730-5039 (512) 794-0100 Technical support fax: (800) 328-2203 (512) 794-5678 Branch Offices: Australia 03 9 879 9422, Austria 0662 45 79 90 0, Belgium 02 757 00 20, Canada (Ontario) 519 622 9310, Canada (Québec) 514 694 8521, Denmark 45 76 26 00, Finland 90 527 2321, France 1 48 14 24 24, Germany 089 741 31 30, Hong Kong 2645 3186, Italy 02 48301892, Japan 03 5472 2970, Korea 02 596 7456, Mexico 95 800 010 0793, Netherlands 0348 433466, Norway 32 84 84 00, Singapore 2265886, Spain 91 640 0085, Sweden 08 730 49 70, Switzerland 056 200 51 51, Taiwan 02 377 1200, U.K. -

Compiling and Debugging Basics

Compiling and Debugging Basics Service CoSiNus IMFT P. Elyakime H. Neau A. Pedrono A. Stoukov Avril 2015 Outline ● Compilers available at IMFT? (Fortran, C and C++) ● Good practices ● Debugging Why? Compilation errors and warning Run time errors and wrong results Fortran specificities C/C++ specificities ● Basic introduction to gdb, valgrind and TotalView IMFT - CoSiNus 2 Compilers on linux platforms ● Gnu compilers: gcc, g++, gfortran ● Intel compilers ( 2 licenses INPT): icc, icpc, ifort ● PGI compiler fortran only (2 licenses INPT): pgf77, pgf90 ● Wrappers mpich2 for MPI codes: mpicc, mpicxx, mpif90 IMFT - CoSiNus 3 Installation ● Gnu compilers: included in linux package (Ubuntu 12.04 LTS, gcc/gfortran version 4.6.3) ● Intel and PGI compilers installed on a centralized server (/PRODCOM), to use it: source /PRODCOM/bin/config.sh # in bash source /PRODCOM/bin/config.csh # in csh/tcsh ● Wrappers mpich2 installed on PRODCOM: FORTRAN : mympi intel # (or pgi or gnu) C/C++ : mympi intel # (or gnu) IMFT - CoSiNus 4 Good practices • Avoid too long source files! • Use a makefile if you have more than one file to compile • In Fortran : ” implicit none” mandatory at the beginning of each program, module and subroutine! • Use compiler’s check options IMFT - CoSiNus 5 Why talk about debugging ? Yesterday, my program was running well: % gfortran myprog.f90 % ./a.out % vmax= 3.3e-2 And today: % gfortran myprog.f90 % ./a.out % Segmentation fault Yet I have not changed anything… Because black magic is not the reason most often, debugging could be helpful! (If you really think that the cause of your problem is evil, no need to apply to CoSiNus, we are not God!) IMFT - CoSiNus 6 Debugging Methodical process to find and fix flows in a code. -

Lecture 15 15.1 Paging

CMPSCI 377 Operating Systems Fall 2009 Lecture 15 Lecturer: Emery Berger Scribe: Bruno Silva,Jim Partan 15.1 Paging In recent lectures, we have been discussing virtual memory. The valid addresses in a process' virtual address space correspond to actual data or code somewhere in the system, either in physical memory or on the disk. Since physical memory is fast and is a limited resource, we use the physical memory as a cache for the disk (another way of saying this is that the physical memory is \backed by" the disk, just as the L1 cache is \backed by" the L2 cache). Just as with any cache, we need to specify our policies for when to read a page into physical memory, when to evict a page from physical memory, and when to write a page from physical memory back to the disk. 15.1.1 Reading Pages into Physical Memory For reading, most operating systems use demand paging. This means that pages are only read from the disk into physical memory when they are needed. In the page table, there is a resident status bit, which says whether or not a valid page resides in physical memory. If the MMU tries to get a physical page number for a valid page which is not resident in physical memory, it issues a pagefault to the operating system. The OS then loads that page from disk, and then returns to the MMU to finish the translation.1 In addition, many operating systems make some use of pre-fetching, which is called pre-paging when used for pages. -

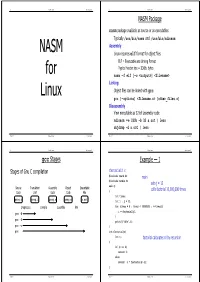

NASM for Linux

1 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II 2 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II NASM Package nasm package available as source or as executables Typically /usr/bin/nasm and /usr/bin/ndisasm Assembly NASM Linux requires elf format for object files ELF = Executable and Linking Format Typical header size = 330h bytes for nasm −f elf [−o <output>] <filename> Linking Linux Object files can be linked with gcc gcc [−options] <filename.o> [other_files.o] Disassembly View executable as 32-bit assembly code ndisasm −e 330h –b 32 a.out | less objdump –d a.out | less Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. Martin Land Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. Martin Land 3 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II 4 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II gcc Stages Example — 1 Stages of Gnu C compilation factorial2.c #include <math.h> main #include <stdio.h> sets j = 12 main() Source Translation Assembly Object Executable calls factorial 10,000,000 times Code Unit Code Code File { int times; prog.c prog.i prog.s prog.o a.out int i , j = 12; preprocess compile assemble link for (times = 0 ; times < 10000000 ; ++times){ i = factorial(j); gcc -E } gcc -S printf("%d\n",i); gcc -c } gcc int factorial(n) int n; factorial calculates n! by recursion { if (n == 0) return 1; else return n * factorial(n-1); } Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. Martin Land Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. Martin Land 5 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II 6 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II Example — 2 Example — 3 ~/gcc$ gcc factorial2.c Compile program as separate files produces executable a.out factorial2a.c ~/gcc$ time a.out main() { 479001600 int times; int i,j=12; for (times = 0 ; times < 10000000 ; ++times){ real 0m9.281s i = factorial(j); factorial2b.c } #include <math.h> printf("%d\n",i); user 0m8.339s #include <stdio.h> } sys 0m0.008s int factorial(n) int n; { Program a.out runs in 8.339 seconds on 300 MHz if (n == 0) Pentium II return 1; else return n * factorial(n-1); } Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. -

Memory Management

Memory management Virtual address space ● Each process in a multi-tasking OS runs in its own memory sandbox called the virtual address space. ● In 32-bit mode this is a 4GB block of memory addresses. ● These virtual addresses are mapped to physical memory by page tables, which are maintained by the operating system kernel and consulted by the processor. ● Each process has its own set of page tables. ● Once virtual addresses are enabled, they apply to all software running in the machine, including the kernel itself. ● Thus a portion of the virtual address space must be reserved to the kernel Kernel and user space ● Kernel might not use 1 GB much physical memory. ● It has that portion of address space available to map whatever physical memory it wishes. ● Kernel space is flagged in the page tables as exclusive to privileged code (ring 2 or lower), hence a page fault is triggered if user-mode programs try to touch it. ● In Linux, kernel space is constantly present and maps the same physical memory in all processes. ● Kernel code and data are always addressable, ready to handle interrupts or system calls at any time. ● By contrast, the mapping for the user-mode portion of the address space changes whenever a process switch happens Kernel virtual address space ● Kernel address space is the area above CONFIG_PAGE_OFFSET. ● For 32-bit, this is configurable at kernel build time. The kernel can be given a different amount of address space as desired. ● Two kinds of addresses in kernel virtual address space – Kernel logical address – Kernel virtual address Kernel logical address ● Allocated with kmalloc() ● Holds all the kernel data structures ● Can never be swapped out ● Virtual addresses are a fixed offset from their physical addresses. -

Memory Management

Memory Management • Peter Rounce - room G06 [email protected] Memory Protection Restrict addresses that an application can access:- • Limits application to its own code and data • Prevents access to other programs and OS • Prevents access to I/O addresses This address restriction is done by Memory Management hardware:- Memory Memory & CPU Address Bus Address Bus Management I/O Interfaces This Memory Management hardware does address translation as well. Memory Protection + Address Translation: Creation of illusion that program has all the memory to itself Logical Memory e.g. for Program X Physical Memory of system Stack Actual memory Unused by mapped by Program X used by Program Program X address translation O/S Data Program Y Code Program, users & CPU’s Physical memory is shared view of memory with other programs/processes used by Program X and with Operating System Solution: have logical addresses used by program and CPU ; have physical addresses to access memory Use Address translation to turn logical address into physical address. Address Translation: basis of Memory Protection and Memory Management MMU Logical address Physical address translation CPU Logical Address Bus MMU Physical Address Bus Memory Bus Error Data bus Logical address Address programmed into code and used by CPU CPU outputs Logical address on to CPU address Bus CPU only knows about Logical addresses Logical address where CPU considers data/instruction to be stored Physical address address where data/instruction is really stored Note:Physical addresses are never stored in the program, only appear on address bus not data bus. MMU = Memory Management Unit Pentium MMU is on same chip as CPU Base-Limit Registers - Memory Protection + Address Translation Several processes J,B,X…. -

RTI Connext DDS Core Libraries Release Notes Version 5.2.0 © 2015 Real-Time Innovations, Inc

RTI Connext DDS Core Libraries Release Notes Version 5.2.0 © 2015 Real-Time Innovations, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. First printing. June 2015. Trademarks Real-Time Innovations, RTI, NDDS, RTI Data Distribution Service, DataBus, Connext, Micro DDS, the RTI logo, 1RTI and the phrase, “Your Systems. Working as one,” are registered trade- marks, trademarks or service marks of Real-Time Innovations, Inc. All other trademarks belong to their respective owners. Copy and Use Restrictions No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form (including electronic, mechanical, photocopy, and facsimile) without the prior written per- mission of Real-Time Innovations, Inc. The software described in this document is furnished under and subject to the RTI software license agreement. The software may be used or copied only under the terms of the license agreement. Technical Support Real-Time Innovations, Inc. 232 E. Java Drive Sunnyvale, CA 94089 Phone: (408) 990-7444 Email: [email protected] Website: https://support.rti.com/ Chapter 1 Introduction 14 Chapter 2 System Requirements 2.1 Supported Operating Systems 1 2.2 Requirements when Using Microsoft Visual Studio 3 2.3 Disk and Memory Usage 4 2.4 Networking Support 4 Chapter 2 Transitioning from 5.1 to 5.2 6 Chapter 3 Compatibility 3.1 Wire Protocol Compatibility 7 3.1.1 General Information on RTPS (All Releases) 7 3.1.2 Release-Specific Information for Connext DDS 5.x 7 3.1.2.1 Large Data with Endpoint Discovery 7 3.1.3 Release-Specific -

ENCM 335 Fall 2018 Lab 3 for the Week of October 1

page 1 of 11 ENCM 335 Fall 2018 Lab 3 for the Week of October 1 Steve Norman Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering University of Calgary September 2018 Lab instructions and other documents for ENCM 335 can be found at https://people.ucalgary.ca/~norman/encm335fall2018/ Administrative details Each student must hand in their own assignment Later in the course, you may be allowed to work in pairs on some assignments. Due Dates The Due Date for this assignment is 3:30pm Friday, October 5. The Late Due Date is 3:30pm Tuesday, October 9 (not Monday the 8th, because that is a holiday). The penalty for handing in an assignment after the Due Date but before the Late Due Date is 3 marks. In other words, X/Y becomes (X{3)/Y if the assignment is late. There will be no credit for assignments turned in after the Late Due Date; they will be returned unmarked. Marking scheme A 4 marks B 8 marks C unmarked D 2 marks E 8 marks F 2 marks G 4 marks total 28 marks How to package and hand in your assignments Please see the information in the Lab 1 instructions. Function interface comments, continued For Lab 2, you were asked to read a document called \Function Interface Com- ments". ENCM 335 Fall 2018 Lab 3 page 2 of 11 Figure 1: Sketch of a program with a function to find the average element value of an array of ints. The function can be given only one argument, and the function is supposed to work correctly for whatever number of elements the array has.