Memory Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of California at Berkeley College of Engineering Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

University of California at Berkeley College of Engineering Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science EECS 61C, Fall 2003 Lab 2: Strings and pointers; the GDB debugger PRELIMINARY VERSION Goals To learn to use the gdb debugger to debug string and pointer programs in C. Reading Sections 5.1-5.5, in K&R GDB Reference Card (linked to class page under “resources.”) Optional: Complete GDB documentation (http://www.gnu.org/manual/gdb-5.1.1/gdb.html) Note: GDB currently only works on the following machines: • torus.cs.berkeley.edu • rhombus.cs.berkeley.edu • pentagon.cs.berkeley.edu Please ssh into one of these machines before starting the lab. Basic tasks in GDB There are two ways to start the debugger: 1. In EMACS, type M-x gdb, then type gdb <filename> 2. Run gdb <filename> from the command line The following are fundamental operations in gdb. Please make sure you know the gdb commands for the following operations before you proceed. 1. How do you run a program in gdb? 2. How do you pass arguments to a program when using gdb? 3. How do you set a breakpoint in a program? 4. How do you set a breakpoint which which only occurs when a set of conditions is true (eg when certain variables are a certain value)? 5. How do you execute the next line of C code in the program after a break? 1 6. If the next line is a function call, you'll execute the call in one step. How do you execute the C code, line by line, inside the function call? 7. -

Memory Layout and Access Chapter Four

Memory Layout and Access Chapter Four Chapter One discussed the basic format for data in memory. Chapter Three covered how a computer system physically organizes that data. This chapter discusses how the 80x86 CPUs access data in memory. 4.0 Chapter Overview This chapter forms an important bridge between sections one and two (Machine Organization and Basic Assembly Language, respectively). From the point of view of machine organization, this chapter discusses memory addressing, memory organization, CPU addressing modes, and data representation in memory. From the assembly language programming point of view, this chapter discusses the 80x86 register sets, the 80x86 mem- ory addressing modes, and composite data types. This is a pivotal chapter. If you do not understand the material in this chapter, you will have difficulty understanding the chap- ters that follow. Therefore, you should study this chapter carefully before proceeding. This chapter begins by discussing the registers on the 80x86 processors. These proces- sors provide a set of general purpose registers, segment registers, and some special pur- pose registers. Certain members of the family provide additional registers, although typical application do not use them. After presenting the registers, this chapter describes memory organization and seg- mentation on the 80x86. Segmentation is a difficult concept to many beginning 80x86 assembly language programmers. Indeed, this text tends to avoid using segmented addressing throughout the introductory chapters. Nevertheless, segmentation is a power- ful concept that you must become comfortable with if you intend to write non-trivial 80x86 programs. 80x86 memory addressing modes are, perhaps, the most important topic in this chap- ter. -

Advanced Practical Programming for Scientists

Advanced practical Programming for Scientists Thorsten Koch Zuse Institute Berlin TU Berlin SS2017 The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters (part 1) ▶︎ Beautiful is better than ugly. ▶︎ Explicit is better than implicit. ▶︎ Simple is better than complex. ▶︎ Complex is better than complicated. ▶︎ Flat is better than nested. ▶︎ Sparse is better than dense. ▶︎ Readability counts. ▶︎ Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules. ▶︎ Although practicality beats purity. ▶︎ Errors should never pass silently. ▶︎ Unless explicitly silenced. ▶︎ In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess. Advanced Programming 78 Ex1 again • Remember: store the data and compute the geometric mean on this stored data. • If it is not obvious how to compile your program, add a REAME file or a comment at the beginning • It should run as ex1 filenname • If you need to start something (python, python3, ...) provide an executable script named ex1 which calls your program, e.g. #/bin/bash python3 ex1.py $1 • Compare the number of valid values. If you have a lower number, you are missing something. If you have a higher number, send me the wrong line I am missing. File: ex1-100.dat with 100001235 lines Valid values Loc0: 50004466 with GeoMean: 36.781736 Valid values Loc1: 49994581 with GeoMean: 36.782583 Advanced Programming 79 Exercise 1: File Format (more detail) Each line should consists of • a sequence-number, • a location (1 or 2), and • a floating point value > 0. Empty lines are allowed. Comments can start a ”#”. Anything including and after “#” on a line should be ignored. -

Virtual Memory Basics

Operating Systems Virtual Memory Basics Peter Lipp, Daniel Gruss 2021-03-04 Table of contents 1. Address Translation First Idea: Base and Bound Segmentation Simple Paging Multi-level Paging 2. Address Translation on x86 processors Address Translation pointers point to objects etc. transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data enables number of advanced features programmers perspective: Address Translation OS in control of address translation pointers point to objects etc. transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data programmers perspective: Address Translation OS in control of address translation enables number of advanced features pointers point to objects etc. transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data Address Translation OS in control of address translation enables number of advanced features programmers perspective: transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data Address Translation OS in control of address translation enables number of advanced features programmers perspective: pointers point to objects etc. Address Translation OS in control of address translation enables number of advanced features programmers perspective: pointers point to objects etc. transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data Address Translation - Idea / Overview Shared libraries, interprocess communication Multiple regions for dynamic allocation -

Compiling and Debugging Basics

Compiling and Debugging Basics Service CoSiNus IMFT P. Elyakime H. Neau A. Pedrono A. Stoukov Avril 2015 Outline ● Compilers available at IMFT? (Fortran, C and C++) ● Good practices ● Debugging Why? Compilation errors and warning Run time errors and wrong results Fortran specificities C/C++ specificities ● Basic introduction to gdb, valgrind and TotalView IMFT - CoSiNus 2 Compilers on linux platforms ● Gnu compilers: gcc, g++, gfortran ● Intel compilers ( 2 licenses INPT): icc, icpc, ifort ● PGI compiler fortran only (2 licenses INPT): pgf77, pgf90 ● Wrappers mpich2 for MPI codes: mpicc, mpicxx, mpif90 IMFT - CoSiNus 3 Installation ● Gnu compilers: included in linux package (Ubuntu 12.04 LTS, gcc/gfortran version 4.6.3) ● Intel and PGI compilers installed on a centralized server (/PRODCOM), to use it: source /PRODCOM/bin/config.sh # in bash source /PRODCOM/bin/config.csh # in csh/tcsh ● Wrappers mpich2 installed on PRODCOM: FORTRAN : mympi intel # (or pgi or gnu) C/C++ : mympi intel # (or gnu) IMFT - CoSiNus 4 Good practices • Avoid too long source files! • Use a makefile if you have more than one file to compile • In Fortran : ” implicit none” mandatory at the beginning of each program, module and subroutine! • Use compiler’s check options IMFT - CoSiNus 5 Why talk about debugging ? Yesterday, my program was running well: % gfortran myprog.f90 % ./a.out % vmax= 3.3e-2 And today: % gfortran myprog.f90 % ./a.out % Segmentation fault Yet I have not changed anything… Because black magic is not the reason most often, debugging could be helpful! (If you really think that the cause of your problem is evil, no need to apply to CoSiNus, we are not God!) IMFT - CoSiNus 6 Debugging Methodical process to find and fix flows in a code. -

Lecture 15 15.1 Paging

CMPSCI 377 Operating Systems Fall 2009 Lecture 15 Lecturer: Emery Berger Scribe: Bruno Silva,Jim Partan 15.1 Paging In recent lectures, we have been discussing virtual memory. The valid addresses in a process' virtual address space correspond to actual data or code somewhere in the system, either in physical memory or on the disk. Since physical memory is fast and is a limited resource, we use the physical memory as a cache for the disk (another way of saying this is that the physical memory is \backed by" the disk, just as the L1 cache is \backed by" the L2 cache). Just as with any cache, we need to specify our policies for when to read a page into physical memory, when to evict a page from physical memory, and when to write a page from physical memory back to the disk. 15.1.1 Reading Pages into Physical Memory For reading, most operating systems use demand paging. This means that pages are only read from the disk into physical memory when they are needed. In the page table, there is a resident status bit, which says whether or not a valid page resides in physical memory. If the MMU tries to get a physical page number for a valid page which is not resident in physical memory, it issues a pagefault to the operating system. The OS then loads that page from disk, and then returns to the MMU to finish the translation.1 In addition, many operating systems make some use of pre-fetching, which is called pre-paging when used for pages. -

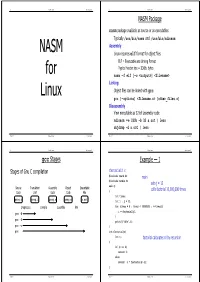

NASM for Linux

1 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II 2 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II NASM Package nasm package available as source or as executables Typically /usr/bin/nasm and /usr/bin/ndisasm Assembly NASM Linux requires elf format for object files ELF = Executable and Linking Format Typical header size = 330h bytes for nasm −f elf [−o <output>] <filename> Linking Linux Object files can be linked with gcc gcc [−options] <filename.o> [other_files.o] Disassembly View executable as 32-bit assembly code ndisasm −e 330h –b 32 a.out | less objdump –d a.out | less Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. Martin Land Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. Martin Land 3 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II 4 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II gcc Stages Example — 1 Stages of Gnu C compilation factorial2.c #include <math.h> main #include <stdio.h> sets j = 12 main() Source Translation Assembly Object Executable calls factorial 10,000,000 times Code Unit Code Code File { int times; prog.c prog.i prog.s prog.o a.out int i , j = 12; preprocess compile assemble link for (times = 0 ; times < 10000000 ; ++times){ i = factorial(j); gcc -E } gcc -S printf("%d\n",i); gcc -c } gcc int factorial(n) int n; factorial calculates n! by recursion { if (n == 0) return 1; else return n * factorial(n-1); } Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. Martin Land Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. Martin Land 5 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II 6 NASM for Linux Microprocessors II Example — 2 Example — 3 ~/gcc$ gcc factorial2.c Compile program as separate files produces executable a.out factorial2a.c ~/gcc$ time a.out main() { 479001600 int times; int i,j=12; for (times = 0 ; times < 10000000 ; ++times){ real 0m9.281s i = factorial(j); factorial2b.c } #include <math.h> printf("%d\n",i); user 0m8.339s #include <stdio.h> } sys 0m0.008s int factorial(n) int n; { Program a.out runs in 8.339 seconds on 300 MHz if (n == 0) Pentium II return 1; else return n * factorial(n-1); } Fall 2007 Hadassah College Dr. -

ENCM 335 Fall 2018 Lab 3 for the Week of October 1

page 1 of 11 ENCM 335 Fall 2018 Lab 3 for the Week of October 1 Steve Norman Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering University of Calgary September 2018 Lab instructions and other documents for ENCM 335 can be found at https://people.ucalgary.ca/~norman/encm335fall2018/ Administrative details Each student must hand in their own assignment Later in the course, you may be allowed to work in pairs on some assignments. Due Dates The Due Date for this assignment is 3:30pm Friday, October 5. The Late Due Date is 3:30pm Tuesday, October 9 (not Monday the 8th, because that is a holiday). The penalty for handing in an assignment after the Due Date but before the Late Due Date is 3 marks. In other words, X/Y becomes (X{3)/Y if the assignment is late. There will be no credit for assignments turned in after the Late Due Date; they will be returned unmarked. Marking scheme A 4 marks B 8 marks C unmarked D 2 marks E 8 marks F 2 marks G 4 marks total 28 marks How to package and hand in your assignments Please see the information in the Lab 1 instructions. Function interface comments, continued For Lab 2, you were asked to read a document called \Function Interface Com- ments". ENCM 335 Fall 2018 Lab 3 page 2 of 11 Figure 1: Sketch of a program with a function to find the average element value of an array of ints. The function can be given only one argument, and the function is supposed to work correctly for whatever number of elements the array has. -

Theory of Operating Systems

Exam Review ● booting ● I/O hardware, DMA, I/O software ● device drivers ● virtual memory 1 booting ● hardware is configured to execute a program in Read-Only Memory (ROM) or flash memory: – the BIOS, basic I/O system – UEFI is the current equivalent ● BIOS knows how to access all the disk drives, chooses one to boot (perhaps with user assistance), loads the first sector (512 bytes) into memory, and starts to execute it (jmp) – first sector often includes a partition table 2 I/O hardware and DMA ● electronics, and sometimes moving parts, e.g. for disks or printers ● status registers and control registers read and set by CPU software – registers can directly control hardware, or be read and set by the device controller ● device controller can be instructed to do Direct Memory Access to transfer data to and from the CPU's memory – DMA typically uses physical addresses 3 Structure of I/O software ● user programs request I/O: read/write, send/recv, etc – daemons and servers work autonomously ● device-independent software converts the request to a device-dependent operation, and also handles requests from device drivers – e.g file systems and protocol stacks – e.g. servers in Minix ● one device driver may manage multiple devices – and handles interrupts ● buffer management required! 4 Device Drivers ● configure the device or device controller – i.e. must know specifics about the hardware ● respond to I/O requests from higher-level software: read, write, ioctl ● respond to interrupts, usually by reading status registers, writing to control registers, and transferring data (either via DMA, or by reading and writing data registers) 5 Memory Management ● linear array of memory locations ● memory is either divided into fixed-sized units (e.g. -

Theory of Operating Systems

Exam Review ● booting ● I/O hardware, DMA, I/O software ● device drivers ● memory (i.e. address space) management ● virtual memory 1 booting ● hardware is configured to execute a program in Read-Only Memory (ROM) or flash memory: – the BIOS, basic I/O system – UEFI is the current equivalent ● BIOS knows how to access all the disk drives, chooses one to boot (perhaps with user assistance), loads the first sector (512 bytes) into memory, and starts to execute it (jmp) – first sector often includes a partition table 2 I/O hardware and DMA ● electronics, and sometimes (disks, printers) moving parts ● status registers and control registers read and set by CPU software – registers can directly control hardware, or be read and set by the device controller ● device controller can be instructed to do Direct Memory Access to transfer data to and from the CPU's memory – DMA typically uses physical addresses 3 Structure of I/O software ● user programs request I/O: read/write, send/recv, etc – daemons and servers work autonomously ● device-independent software converts the request to a device-dependent operation, and also handles requests from device drivers – e.g file systems and protocol stacks – e.g. servers in Minix ● one device driver may manage multiple devices – and handles interrupts ● buffer management required! 4 Device Drivers ● configure the device or device controller – i.e. must know specifics about the hardware ● respond to I/O requests from higher-level software: read, write, ioctl ● respond to interrupts, usually by reading status registers, writing to control registers, and transferring data (either via DMA, or by reading and writing data registers) 5 Memory Management ● linear array of memory locations ● memory is either divided into fixed-sized units (e.g. -

Smashing the Stack in 2011 | My

my 20% hacking, breaking things, malware, free time, etc. Home About Me Undergraduate Thesis (TRECC) Type text to search here... Home > Uncategorized > Smashing the Stack in 2011 Smashing the Stack in 2011 January 25, 2011 Recently, as part of Professor Brumley‘s Vulnerability, Defense Systems, and Malware Analysis class at Carnegie Mellon, I took another look at Aleph One (Elias Levy)’s Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit article which had originally appeared in Phrack and on Bugtraq in November of 1996. Newcomers to exploit development are often still referred (and rightly so) to Aleph’s paper. Smashing the Stack was the first lucid tutorial on the topic of exploiting stack based buffer overflow vulnerabilities. Perhaps even more important was Smashing the Stack‘s ability to force the reader to think like an attacker. While the specifics mentioned in the paper apply only to stack based buffer overflows, the thought process that Aleph suggested to the reader is one that will yield success in any type of exploit development. (Un)fortunately for today’s would be exploit developer, much has changed since 1996, and unless Aleph’s tutorial is carried out with additional instructions or on a particularly old machine, some of the exercises presented in Smashing the Stack will no longer work. There are a number of reasons for this, some incidental, some intentional. I attempt to enumerate the intentional hurdles here and provide instruction for overcoming some of the challenges that fifteen years of exploit defense research has presented to the attacker. An effort is made to maintain the tutorial feel of Aleph’s article. -

UNIVERSITY of CAMBRIDGE Computer Laboratory

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Computer Laboratory Computer Science Tripos Part Ib Compiler Construction http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/Teaching/1112/CompConstr/ David J Greaves [email protected] 2011–2012 (Lent Term) Notes and slides: thanks due to Prof Alan Mycroft and his predecessors. Summary The first part of this course covers the design of the various parts of a fairly basic compiler for a pretty minimal language. The second part of the course considers various language features and concepts common to many programming languages, together with an outline of the kind of run-time data structures and operations they require. The course is intended to study compilation of a range of languages and accordingly syntax for example constructs will be taken from various languages (with the intention that the particular choice of syntax is reasonably clear). The target language of a compiler is generally machine code for some processor; this course will only use instructions common (modulo spelling) to x86, ARM and MIPS—with MIPS being favoured because of its use in the Part Ib course “Computer Design”. In terms of programming languages in which parts of compilers themselves are to be written, the preference varies between pseudo-code (as per the ‘Data Structures and Algorithms’ course) and language features (essentially) common to C/C++/Java/ML. The following books contain material relevant to the course. Compilers—Principles, Techniques, and Tools A.V.Aho, R.Sethi and J.D.Ullman Addison-Wesley (1986) Ellis Horwood (1982) Compiler Design in Java/C/ML (3