Spatial Shifts in the Location of Slaughterhouses in Mumbai City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Experiences of Low Income Communities in Mumbai Vis-À-Vis

222 223 _Amita Bhide From The Margins: The Experiences of Low Income Communities In Mumbai vis-à-vis Changing patterns of Basic Service Delivery image credit_ Aditi Pinto image credit_ 224 chunk of urban population, which can no longer delivery has been considered a state arena by These are described below: 225 | | Basic service delivery - a be ignored or rendered invisible. As Robert Classical economists on the basis of potential The Phase of Negation AMENITY traditional function of urban local governments McNamara, the former President of the World private market failures. Partnerships through Slums were seen as unfit housing and dens of AMENITY represents one of the most concrete forms Bank said ‘If cities do not deal with the problems outsourcing and contracting attempt to get crime in the initial years of planning and the of governance for urban citizens. Thereby, of the poor in a constructive way, they will deal over these failures, through partial privatisation. concern was to demolish these and replace with changes in forms of local governance through with cities in a destructive way’. Addressing the (RCUES, 2005). Several cities in India have ‘acceptable’ housing. Thus, the Slum Clearance decentralisation and responses to globalisation issues of providing infrastructure to expanding, thus, engaged in partnerships in areas of Programme of 1956 vested the governments with can be expected to be operationalised through big and poor cities is the real challenge of date. service delivery such as electricity and water necessary powers to compulsorily acquire slum new modes of organising service delivery. supply, solid waste collection, transportation areas and redevelop them. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

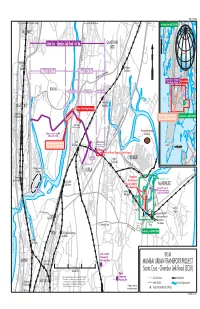

Chembur Link Road (SCLR) Matunga to Mumbai Rail Station This Map Was Produced by the Map Design Unit of the World Bank

IBRD 33539R To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road / Borivali To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road To Thane To Thane For Detail, See IBRD 33538R VILE PARLE ek re GHATKOPAR C i r Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km o n a SATIS M Mumbai THANE (Kurla-Andhai Road) Vile Parle ek re S. Mathuradas Vasanji Marg C Rail alad Station Ghatkopar M Y Rail Station N A Phase II: 3.0 km Phase I: 3.4 km TER SW S ES A E PR X Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg WESTERN EXPRESSWAY E Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km Area of Map KALINA Section 1: 1.25 km Section 2: 1.55 km Section 3: .6 km ARABIAN Swami Vivekananda Marg SEA Vidya Vihar Thane Creek SANTA CRUZ Rail Station Area of Gazi Nagar Request Mahim Bay Santa Cruz Rail Station Area of Shopkeepers' Request For Detail, See IBRD 33540R For Detail, See IBRD 33314R MIG Colony* (Middle Income Group) Central Railway Deonar Dumping 500m west of river and Ground 200m south of SCLR Eastern Expressway R. Chemburkar Marg Area of Shopkeepers' Request Kurla MHADA Colony* CHURCHGATE CST (Maharashtra Housing MUMBAI 012345 For Detail, See IBRD 33314R Rail Station and Area Development Authority) KILOMETERS Western Expressway Area of Bharathi Nagar Association Request S.G. Barve Marg (East) Gha Uran Section 2 Chembur tko CHEMBUR Rail Station parM ankh urdLink Bandra-Kurla R Mithi River oad To Vashi Complex KURLA nar Nala Deo Permanent Bandra Coastal Regulation Zones Rail Station Chuna Batti Resettlement Rail Station Housing Complex MANKHURD at Mankhurd Occupied Permanent MMRDA Resettlement Housing Offices Govandi Complex at Mankhurd Rail Station Deonar Village Road Mandala Deonarpada l anve Village P Integrated Bus Rail Sion Agarwadi Interchange Terminal Rail Station Mankhurd Mankhurd Correction ombay Rail Station R. -

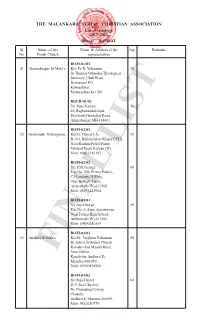

Diocese of Bombay

THE MALANKARA SYRIAN CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION List of Members 2017- 2022 Diocese : BOMBAY Sl. Name of the Name & Address of the Age Remarks No. Parish Church representatives BOM-01/01 01 Ahamednagar St.Mary’s Rev. Fr. K. Yohannan 38 St. Thomas Orthodox Theological Seminary, Ubali Road Brahamani P.O. Kalmeshwar, Maharashtra 441 501 BGLR-01/02 Sri. Peter Kurien 56 #4, Raghunandan Apts., Delvimala Gulmohar Road, Ahmedangar, MH 414001. BOM-02/01 02 Ambernath St.Gregorios Rev.Fr. Daniel T.A. 55 B-101, Ballaleshwar Krupa C.H.S., Near Roshan Petrol Pump, Murbad Road, Kalyan (W). Mob: 09422385193 BOM-02/02 Sri. P.M. George 69 Flat No. 206, Prince Palace, C.H. society, B Wing, Opp. Bethal Church, Ambernath (W) 421505. Mob: 09673223962 BOM-02/03 Sri. Saji George 59 Flat No. 6, Anne Appartment, Near Fatima High School, Ambernath (W) 421505. Mob: 09890240109 BOM-03/01 03 Andheri St.John’s Rev.Fr. Varghese Yohannan 54 St. John’s Orthodox Church Ramakrishna Mandir Road, FINALNear Pidilite, LIST Kondivitta, Andheri (E), Mumbai 400 059. Mob: 09969496900 BOM-03/02 Sri. Raju Daniel 64 D-9, Iree Chs Atd, Dr. Charatsing Colony, Chakala, Andheri E, Mumbai 400093. Mob: 9820230779 2 BOM-03/03 Sri. Joy Thomas 55 Flat No. 202, Bracke Rose CHS Ltd., Mahakali Caves Rd., Andheri E, Mumbai 400093. Mob: 9967642853 BOM-03/04 Sri. Reji Samuel 44 B-208, Kamlesh Apts, Sher E, Punjab Plot No. 287, Andheri E, Mumbai 400093. BOM-04/01 04 Aurangabad St.Mary’s Rev.Fr. Thomaskutty C. 41 Orthodox Church Centre, Dr. -

List of Indian Abattoirs Approved by Apeda

A – APPROVED INDIAN ABATTOIRS-CUM-MEAT PROCESSING PLANTS / STAND ALONE ABATTOIRS S. No. Name of the Exporter and Unit(s) approved by APEDA Registration Products Registration Contact Person No. permitted validity up for export to 1. Cdr. Satish Subberwal M/s Al-Kabeer Exports (P) APEDA/16 Buffalo/ 26/08/2016 Director Ltd. Sheep and Goat M/s. Al Kabeer Exports (P) Ltd. Village : Rudaram meat 53, Jolly Maker Chamber No. 2 Patancheru Mandal Nariman Point, Distt. Medak, Mumbai-400021 Andhra Pradesh Tel: 022-22025768 Fax: 022-22028475 E-Mail: [email protected] 2. Mr. Afzal Latif M/s. Frigorifico Allana Private APEDA/20 Buffalo/ Sheep 30/11/2016 President Limited. and Goat meat M/s. Allanasons Private Limited. P.O. Box –14, Paithan Road, Allana Centre, Gevrai, Aurangabad-431002 113/115, M.G. Road, Fort, Maharashtra Mumbai – 400001 (Plant – I) Tel: 022-56569000, 22628000, 56569056 Fax 022-22641133, 22691133 E-Mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 3. Mr. Afzal Latif M/s. Frigerio Conserva Allana APEDA/21 Buffalo/ Sheep 30/11/2016 President Private Limited. and Goat meat M/s. Allanasons Private Limited. Survey No. 325, Allana Centre, IDA, Algole Road, 113/115, M.G. Road, Fort, Zaheerabad-520220, Distt.: Mumbai – 400001 Medak Tel: 022-56569000, 22628000, Andhra Pradesh 56569056 Fax 022-22641133, 22691133 E-Mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 4. Mr. Afzal Latif b. M/s Frigorifico Allana APEDA/23 Buffalo/ Sheep 30/11/2016 President Private Limited. and Goat meat M/s. Allanasons Private Limited. P.O. Box 564, Paithan Road, Allana Centre, Gevrai 113/115, M.G. -

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 15 Annexure - I 16 – 45 Annexure - II 45 - 48 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District 1. -

Islam As a Lived Tradition

Islam as a Lived Tradition: Ethical Constellations of Muslim Food Practice in Mumbai Een verklaring van Islam als een Levende Traditie: Ethische Constellaties van Moslim Voedsel Praktijken in Mumbai (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 10 mei 2017 des middags te 2.30 uur door Shaheed Tayob geboren op 28 juni 1984 te Kaapstad, Zuid Afrika 1A_BW proefschrift Shaheed Tayob[pr].job Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................... i Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ iv Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. vii Chapter One: Islam as a Lived Tradition: The Ethics of Muslim Food Practices in Mumbai .................................................................................................................. 1 From Bombay to Mumbai: The Shifting Place of Muslims in the City .................................................. 3 The Anthropology of Islam: A Discursive Analysis ............................................................................... 11 Talal -

Total List of MCGM and Private Facilities.Xlsx

MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF GREATER MUMBAI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARIES SR SR WARD NAME OF THE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ADDRESS NO NO 1 1 COLABA MUNICIPALMUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 1ST FLOOR, COLOBA MARKET, LALA NIGAM ROAD, COLABA MUMBAI 400 005 SABOO SIDIQUE RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ( 2 2 SABU SIDDIQ ROAD, MUMBAI (UPGRADED) PALTAN RD.) 3 3 MARUTI LANE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARUTI LANE,MUMBAI A 4 4 S B S ROAD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 308, SHAHID BHAGATSINGH MARG, FORT, MUMBAI - 1. 5 5 HEAD OFFICE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 6 6 HEAD OFFICE AYURVEDIC MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 7 1 SVP RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, QUARTERS, A BLOCK, MAUJI RATHOD RD, NOOR BAUG, DONGRI, MUMBAI 400 8 2 WALPAKHADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 009 9B 3 JAIL RD. UNANI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, 10 4 KOLSA MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI 11 5 JAIL RD MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI CHANDANWADI SCHOOL, GR.FLOOR,CHANDANWADI,76-SHRIKANT PALEKAR 12 1 CHANDAN WADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARG,MARINELINES,MUM-002 13 2 THAKURDWAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY THAKURDWAR NAKA,MARINELINES,MUM-002 C PANJRAPOLE HEALTH POST, RAMA GALLI,2ND CROSS LANE,DUNCAN ROAD 14 3 PANJRAPOLE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MUMBAI - 400004 15 4 DUNCAN RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY DUNCAN ROAD, 2ND CROSS GULLY 16 5 GHOGARI MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HAJI HASAN AHMED BAZAR MARG, GOGRI MOHOLLA 17 1 NANA CHOWK MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY NANA CHOWK, FIRE BRIGADE COMPOUND, BYCULLA 18 2 R. S. NIMKAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY R.S NIMKAR MARG, FORAS ROAD, 19 3 R. -

352 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

352 bus time schedule & line map 352 Trombay - Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion) View In Website Mode The 352 bus line (Trombay - Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion): 12:00 AM - 11:43 PM (2) Trombay: 12:04 AM - 11:48 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 352 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 352 bus arriving. Direction: Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion) 352 bus Time Schedule 27 stops Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion) Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:43 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:43 PM Trombay Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:43 PM Dhobi Ghat (Trombay) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:43 PM Cheeta Camp Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:43 PM Narmadeshwar Mandir Friday 12:00 AM - 11:43 PM Mandala Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:43 PM B.A.R.C School No.6 Mankhurd Station Road (S) 352 bus Info Childrens Home Direction: Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion) Stops: 27 Trip Duration: 27 min Anushakti Nagar Line Summary: Trombay, Dhobi Ghat (Trombay), V.N. Purav Marg, Mumbai Cheeta Camp, Narmadeshwar Mandir, Mandala, B.A.R.C School No.6, Mankhurd Station Road (S), Raj Kapoor Chowk / Bhabha Hospital Childrens Home, Anushakti Nagar, Raj Kapoor Chowk / Bhabha Hospital, Telecom Factory, Telecom Factory Punjabwadi, Deonar Depot, R.K.Studio, Maitri Park, Deonar Govandi Road, Mumbai R.B.I Colony (Chembur), Acharya Garden/ Diamond Garden, Acharya Garden / Diamond Garden, Sandu Punjabwadi Wadi, Chembur Naka / Swami Vivekanand Chowk, Kumbhar Wada, Umarshi Bappa Chowk, Deonar Depot Priyadarshani Chuna -

Standard Bid Document

E-TENDER FOR Subject :- Work of replacement of pumps & blowers with Providing, Installation, Testing & Commissioning of new pump and blowers set for ETP at Deonar Abattoir. STANDARD BID DOCUMENT Website: portal.mcgm.gov.in/tenders Office of: General Manager (Deonar Abattoir), Opp. Govandi Rly Station Govandi,West Mumbai- 400 043 INDEX SECTION DESCRIPTION 1 E-TENDER NOTICE 2 ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA 3 DISCLAIMER 4 INTRODUCTION 5 E-TENDER ONLINE SUBMISSION PROCESS 6 INSTRUCTIONS TO APPLICANTS 7 SCOPE OF WORK 8 BILL OF QUANTITIES 9 GENERAL CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT 10 SPECIFICATIONS 11 FRAUD AND CORRUPT PRACTICES 12 PRE-BID MEETING 13 LIST OF APPROVED BANKS 14 APPENDIX SECTION 1 E-TENDER NOTICE MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF GREATER MUMBAI Deonar Abattoir No. GMDA/ / Exp E-TENDER NOTICE Sub : Work of replacement of pumps & blowers with Providing, Installation, Testing & Commissioning of new pump and blowers set for ETP at Deonar Abattoir. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) invites e-tender to appoint Contractor for the aforementioned work from contractors of repute, multidisciplinary engineering organizations i.e. eminent firm, Proprietary/Partnership Firms/ Private Limited Companies/ Public Limited Companies/Companies registered under the Indian companies’ act 2013 , the contractors registered with the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai, (MCGM) in Class AA (Mech&Elect. category) as per old registration OR Class B (Mech &Elect. category) as per new registration and from the contractors/firms equivalent and superior classes registered in Central or State Government/Semi Govt. Organization/Central or State Public Sector Undertakings, will be allowed subject to condition that, the contractors who are not registered with MCGM will have to apply for registering their firm within three months time period from the award of contract, otherwise their Bid Security i.e. -

Visceral Politics of Food: the Bio-Moral Economy of Work- Lunch in Mumbai, India

Visceral politics of food: the bio-moral economy of work- lunch in Mumbai, India Ken Kuroda London School of Economics and Political Science A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2018 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98896 words. 2 Abstract This Ph.D. examines how commuters in Mumbai, India, negotiate their sense of being and wellbeing through their engagements with food in the city. It focuses on the widespread practice of eating homemade lunches in the workplace, important for commuters to replenish mind and body with foods that embody their specific family backgrounds, in a society where religious, caste, class, and community markers comprise complex dietary regimes. Eating such charged substances in the office canteen was essential in reproducing selfhood and social distinction within Mumbai’s cosmopolitan environment. -

Assessments for Scientific Pre- Closure of Deonar Dumping Site, Mumbai and Development of Project Monitoring Plan”

Expression of Interest (EOI) for “Assessments for Scientific Pre- Closure of Deonar Dumping Site, Mumbai and Development of Project Monitoring Plan” Work Location: Deonar Mumbai CSIR-NEERI, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India invites “EOI” from the experienced and knowledgeable internationally respected/recognized Engineering Consultants in the field of site assessment work for scientific closure of Municipal Solid Waste Dumping site, preparation of plans, drawing and cost estimate including ‘Project Monitoring Plan 1. BACKGROUND The Government of India issued Notification for proper storage, collection, treatment, and disposal of Municipal Solid Waste through Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules, 2016. As per SWM Rules 2016, existing dumpsites need to be closed scientifically. In accordance with these rules, CSIR-NEERI is undertaking the task for suggesting appropriate technology for scientific closure of certain portion of the site, bio-mining / bio remediation and disposal of legacy waste by preparation of appropriate plan by examining all kinds of feasibilities for closure of the site and making available portion of the site for Solid Waste Processing facility by analyzing the site characteristics and overall study by themselves and through also experienced Engineering consultant. It is also necessary to prepare “Project Monitoring Plan” at a later stage. Accordingly, CSIR-NEERI proposed to conduct a detailed study to select the appropriate technology for the closure of the landfill depending on site survey, contour mapping, topographical, geological and hydro-geological studies conducted at the dumpsite. Therefore, in order to carry out precise work, CSIR-NEERI is inviting “Expression of Interest (EOI)” from renowned Engineering consultants having experience in this field and willing to undertake the work as defined in the scope by themselves or in association with other agencies for conducting the work.