Garlet: Rediscovery of a Laird's House in Clackmannanshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotlight Central and Tayside Residential Market Summer 2016

Savills World Research UK Residential Spotlight Central and Tayside Residential Market Summer 2016 Drumfada (Offers Over £540,000) in Dundee, where overall transactional activity increased annually by 13%. SUMMARY Growing confidence in lower price brackets fuels prime activity across Central and Tayside ■ The market below £400,000 across FIGURE 1 Central and Tayside has outperformed Residential values annual change forecast Scotland and continues to attract second home owners and downsizers Area 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 from outside the region. Prime GB regional 2.5% 3.5% 6.0% 4.5% 4.0% ■ Strong growth across lower price bands is now leading to improved Prime Scotland 2.0% 3.5% 4.0% 4.0% 4.0% prime activity in the city and town locations of Angus, Dundee, Fife, Prime Central & Tayside 1.0% 2.5% 3.5% 3.5% 3.5% Stirling, and Perth. Mainstream UK 5.0% 3.0% 3.0% 2.5% 2.5% ■ The prime market has adjusted to Mainstream Scotland 3.0% 3.0% 2.5% 2.5% 2.5% taxation changes in the city hotspots of Edinburgh and Glasgow, with Mainstream Central & Tayside 2.5% 2.5% 2.0% 2.0% 2.0% growth spreading into traditional suburbs and commuter areas. Source: Savills Research savills.co.uk/research 01 Spotlight | Central and Tayside Residential Market CENTRAL AND to the city hubs of Edinburgh and Stirling city and the hotspots of Glasgow. As a consequence, there Dollar, Dunblane and Killearn. Tayside MARKET will be opportunities for buyers to take advantage of relative The Fife market was in line with affordability (Figure 1). -

Tayside, Angus and Perthshire Fibromyalgia Support Group Scotland

Tayside, Angus and Perthshire Angus Long Term Conditions Support Fibromyalgia Support Group Scotland Groups Offer help and support to people suffering from fibromyalgia. This help and support also extends to Have 4 groups of friendly people who meet monthly at family and friends of sufferers and people who various locations within Angus and offer support to people would like more information on fibromyalgia. who suffer from any form of Long Term Condition or for ANGUS Directory They meet every first Saturday of every month at carers of someone with a Long Term Condition as well as Ninewells Hospital, Dundee. These meetings are each other, light refreshments are provided. to Local held on Level 7, Promenade Area starting at 11am For more information visit www.altcsg.org.uk or e-mail: Self Help Groups and finish at 1pm. [email protected] For more information contact TAP FM Support Group, PO Box 10183, Dundee DD4 8WT, visit www.tapfm.co.uk or e-mail - [email protected] . Multiple Sclerosis Society Angus Branch For information about, or assistance about the Angus Gatepost Branch please call 0845 900 57 60 between 9am - 8pm or e-mail Brian Robson at mailto:[email protected] GATEPOST is run by Scottish farming charity RSABI and offers a helpline service to anyone who works on the land in Scotland, and also their families. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic They offer a friendly, listening ear and a sounding post for Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) you at difficult times, whatever the reason. If you’re The aims of the support group are to give support to worried, stressed, or feeling isolated, they can help. -

Examining the Test: an Evaluation of the Police Standard Entrance Test. INSTITUTION Scottish Council for Research in Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 249 TM 027 914 AUTHOR Wilson, Valerie; Glissov, Peter; Somekh, Bridget TITLE Examining the Test: An Evaluation of the Police Standard Entrance Test. INSTITUTION Scottish Council for Research in Education. SPONS AGENCY Scottish Office Education and Industry Dept., Edinburgh. ISBN ISBN-0-7480-5554-1 ISSN ISSN-0950-2254 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 104p. AVAILABLE FROM HMSO Bookshop, 71 Lothian Road, Edinburgh, EH3 9AZ; Scotland, United Kingdom (5 British pounds). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Employment Qualifications; Foreign Countries; Job Skills; Minority Groups; *Occupational Tests; *Police; Test Bias; *Test Interpretation; Test Use; *Testing Problems IDENTIFIERS *Scotland ABSTRACT In June 1995, the Scottish Council for Research in Education began a 5-month study of the Standard Entrance Examination (SET) to the police in Scotland. The first phase was an analysis of existing recruitment and selection statistics from the eight Scottish police forces. Phase Two was a study of two police forces using a case study methodology: Identified issues were then circulated using the Delphi approach to all eight forces. There was a consensus that both society and the police are changing, and that disparate functional maps of a police officer's job have been developed. It was generally recognized that recruitment and selection are important, but time-consuming, aspects of police activity. Wide variations were found in practices across the eight forces, including the use of differential pass marks for the SET. Independent assessors have identified anomalies in the test indicating that it is both ambiguous and outdated in part, with differences in the readability of different versions that compromises comparability. -

A Short History of the Temperance Movement in the Hillfoots, by Ian

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE TEMPERANCE MOVEMENT IN THE HILLFOOTS Ian Middleton CONTENTS 2 Introduction: temperance and the Hillfoots 9 Temperance societies in the Hillfoots 9 Total Abstinence Societies 11 Children and the temperance movement: The Band of Hope 12 Young Abstainers’ Unions 13 Working Men’s Yearly Temperance Society 13 The Independent Order of Good Templars 15 British Women’s Temperance Association 17 The Independent Order of Rechabites 17 Gospel temperance 18 Temperance Unions 18 Counter attractions to the public house 21 Appendix: known temperance societies in the Hillfoots 25 Bibliography 2 INTRODUCTION: TEMPERANCE AND THE HILLFOOTS The question whether alcohol is a good or a bad thing has long divided opinion. At the beginning of the 19th century widespread criticism of alcohol gained ground in Britain and elsewhere. Those who advocated abstinence from drink, as well as some who campaigned for prohibition (banning the production, sale and consumption of alcohol) started to band together from the late 1820s onwards. This formal organisation of those opposed to alcohol was new. It was in response to a significant increase in consumption, which in Scotland almost trebled between 1822 and 1829. There were several reasons for this increase. Duty on spirits was lowered in 1822 from 7/- to 2/10d per gallon1 and a new flat tax and license fee system for distillers was introduced in 1823 in an effort to deal with illegal distilling. 2 Considerable numbers of private distillers went legal soon after. Production capacity for spirits was further increased by the introduction of a new, continuous distillation process. -

160420 Attainment and Improvement Sub Committee Agenda

Appendix 1 Appendices Appendix 1: Map of Clackmannanshire & Schools Appendix 2: Areas of Deprivation Appendix 3: Public Health Data Appendix 4: Positive Destinations Appendix 5: School Information Appendix 6: School Data 46 28 AppendixAppendix 11 Map of Clackmannanshire Schools Learning Establishment Geographical Learning Establishment Geographical Community Community Community Community Alloa Academy ABC Nursery Alloa Alva Academy Alva PS Alva Park PS Alloa Coalsnaughton PS Coalsnaughton Redwell PS Alloa Menstrie PS Menstrie St Mungo’s PS Alloa Muckhart PS Muckhart Sunnyside PS Alloa Strathdevon PS Dollar CSSS Alloa Tillicoultry PS Tillicoultry Lochies Sauchie Lornshill Sauchie Nursery Sauchie Academy Abercromby PS Tullibody Banchory PS Tullibody Clackmannan Clackmannan PS Craigbank PS Sauchie Deerpark PS Sauchie Fishcross PS Fishcross St Bernadette’s Tullibody St Serf’s PS Tullibody Improving Life Through Learning 47 AppendixAppendix 21 Areas of Deprivation Employment and Income by Datazone Catchment Data Zone Name % Employment % Income Deprived Deprived Alloa North 15 19 Alloa Alloa South and East 30 38 Academy Alloa West 11 11 Sauchie 19 21 Clackmannan, Kennet and Forestmill 15 16 Lornshill Academy Tullibody South 15 20 Tullibody North and Glenochil 15 19 Menstrie 9 9 Dollar and Muckhart 6 6 Alva Alva 13 16 Academy Tillicoultry 14 17 Fishcross, Devon Village and Coalsnaughton 18 19 Improving Life Through Learning48 AppendixAppendix 31 Public Health Data Improving Life Through Learning 49 AppendixAppendix 41 Positive Destinations Year on Year Positive Destination Trend Analysis Improving Life Through Learning 50 AppendixAppendix 51 School Information Learning Establishment Roll Nursery Class Leadership Community Team Alloa Academy Park 215 48/48 HT, DHT, 1 PT Redwell 432 70/70 HT, 2 DHT, 4 PT St. -

Tillicoultry Estate and the Influence of The

WHO WAS LADY ANNE? A study of the ownership of the Tillicoultry Estate, Clackmannanshire, and the role and influence of the Wardlaw Ramsay Family By Elizabeth Passe Written July 2011 Edited for the Ochils Landscape Partnership, January 2013 Page 1 of 24 CONTENTS Page 2 Contents Page 3 Acknowledgements, introduction, literature review Page 5 Ownership of the estate Page 7 The owners of Tillicoultry House and Estate and their wives Page 10 The owners in the 19th century - Robert Wardlaw - Robert Balfour Wardlaw Ramsay - Robert George Wardlaw Ramsay - Arthur Balcarres Wardlaw Ramsay Page 15 Tenants of Tillicoultry House - Andrew Wauchope - Alexander Mitchell - Daniel Gardner Page 17 Conclusion Page 18 Nomenclature and bibliography Page 21 Appendix: map history showing the estate Figures: Page 5 Fig. 1 Lady Ann’s Wood Page 6 Fig. 2 Ordnance Survey map 1:25000 showing Lady Ann Wood and well marked with a W. Page 12 Fig. 3 Tillicoultry House built in the early 1800s Page 2 of 24 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My grateful thanks are due to: • Margaret Cunningham, my course tutor at the University of Strathclyde, for advice and support • The staff of Clackmannanshire Libraries • Susan Mills, Clackmannanshire Museum and Heritage Officer, for a very useful telephone conversation about Tillicoultry House in the 1930s • Elma Lindsay, a course survivor, for weekly doses of morale boosting INTRODUCTION Who was Lady Anne? This project was originally undertaken to fulfil the requirements for the final project of the University of Strathclyde’s Post-graduate Certificate in Family History and Genealogy in July 2011. My interest in the subject was sparked by living in Lady Anne Grove for many years and by walking in Lady Anne’s Wood and to Lady Anne’s Well near the Kirk Burn at the east end of Tillicoultry. -

Tayside November 2014

Regional Skills Assessment Tayside November 2014 Angus Perth and Kinross Dundee City Acknowledgement The Regional Skills Assessment Steering Group (Skills Development Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, the Scottish Funding Council and the Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group) would like to thank SQW for their highly professional support in the analysis and collation of the data that forms the basis of this Regional Skills Assessment. Regional Skills Assessment Tayside Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Context 5 3 Economic Performance 7 4 Profile of the Workforce 20 5 People and Skills Supply 29 6 Education and Training Provision 43 7 Skills Mismatches 63 8 Economic and Skills Outlook 73 9 Questions Arising 80 sds.co.uk 1 Regional Skills Assessment Section 1 Tayside Introduction 1 Introduction 1.1 The purpose of Regional Skills Assessments This document is one of a series of Regional Skills Assessments (RSAs), which have been produced to provide a high quality and consistent source of evidence about economic and skills performance and delivery at a regional level. The RSAs are intended as a resource that can be used to identify regional strengths and any issues or mismatches arising, and so inform thinking about future planning and investment at a regional level. 1.2 The development and coverage of RSAs The content and geographical coverage of the RSAs was decided by a steering group comprising Skills Development Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, the Scottish Funding Council and extended to include the Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group during the development process. It was influenced by a series of discussions with local authorities and colleges, primarily about the most appropriate geographic breakdown. -

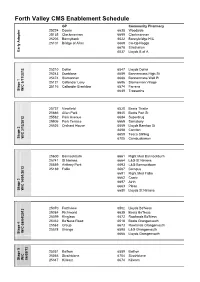

Forth Valley CMS Enablement Schedule

Forth Valley CMS Enablement Schedule GP Community Pharmacy 25224 Doune 6638 Woodside 25135 Clackmannan 6699 Clackmannan 25205 Bonnybank 6522 Bonnybridge H/C 25101 Bridge of Allan 6669 Co-Op Haggs 6678 Strathallan Early Adopter 6537 Lloyds B of A 25210 Dollar 6547 Lloyds Dollar 25243 Dunblane 6689 Bannermans High St 25474 Slamannan 6688 Bannermans Well Pl 25121 Callendar Leny 6696 Slamannan Village 25116 Callander Bracklinn 6574 Farrens Stage 1 W/C 5/11/2012 6649 Trossachs 25737 Viewfield 6520 Boots Thistle 25686 Allan Park 6645 Boots Port St 25582 Park Avenue 6684 Superdrug 25506 Park Terrace 6665 Sainsbury 25525 Orchard House 6559 Lloyds Barnton St 6698 Cornton 6659 Tesco Stirling Stage 2 W/C 3/12/2012 6705 Cambusbarron 25600 Bannockburn 6661 Right Med Bannockburn 25741 St Ninians 6664 L&G St Ninians 25559 Airthrey Park 6693 L&G Bannockburn 25169 Fallin 6687 Campus 6691 Right Med Fallin 6662 Cowie 6697 Airth 6663 Plean Stage 3 W/C 14/01/2013 6680 Lloyds St Ninians 25070 Forthview 6502 Lloyds Bo'Ness 25084 Richmond 6635 Boots Bo'Ness 25099 Kinglass 6672 Rowlands Bo'Ness 25332 Bo'Ness Road 6518 Boots Grangemouth 25563 Group 6673 Rowlands Grangemouth 25578 Grange 6598 L&G Grangemouth Stage 4 W/C 08/04/2013 6668 Lloyds Grangemouth 25051 Balfron 6589 Balfron 25065 Strathblane 6704 Strathblane Stage 5 W/C 06/05/13 25347 Killearn 6674 Killearn 25262 Wallace Falkirk 6516 Boots Falkirk 25277 Booth Pl Dr Ark 6548 Lloyds Thornhill Rd 25281 Meeks Road 6681 Lloyds Grahams Rd 25309 Graeme 6585 Tesco Retail park 25296 Park St 6692 Hallglen Stage 6 W/C -

Numerical Microfiche Listing Fiche No

Numerical Microfiche Listing Fiche No. Description 6000001 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort A 6000002 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort AS 6000003 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort BER-BEU 6000004 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort BEU-CHA 6000005 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort CHA_DON 6000006 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort DON-ELL 6000007 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort ELL-FRA 6000008 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort FRA-GOS 6000009 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort GOS-HAF 6000010 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort HAF-HEL 6000012 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort HUP-KES 6000013 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort KES-KON 6000014 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort KON-LEI 6000015 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort LEI-LUT 6000016 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort LUT-MOI 6000017 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort MOI-NEU 6000018 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort NEU-OBE 6000019 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort OBE-PEL 6000020 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort PEL-RAP 6000021 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort RAP-RUD 6000022 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort RUD-SEN 6000023 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort SCHO-SPA 6000024 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort SPA-SYD 6000025 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort SYD-UTT 6000026 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort UTT-WEN 6000027 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort WEN-WZY 6000028 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort XAN-Z 6000029 Germany-Gazeteers Meyers Ort ANHANG 6000034 Hamburg-Passenger Lists 6000035 Germany-Genealogical Research 6000198 Austro-Hungarian Empire- Military Detail & Topographic Maps-Map Keys 6000199 Austro-Hungarian Empire- Military Detail & Topographic Maps-Block 1 6000200 Austro-Hungarian Empire- Military -

TAYSIDE VALUATION APPEAL PANEL LIST of APPEALS for CONSIDERATION by the VALUATION APPEAL COMMITTEE at Robertson House, Whitefriars Crescent, PERTH on 24 June 2021

TAYSIDE VALUATION APPEAL PANEL LIST OF APPEALS FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE VALUATION APPEAL COMMITTEE At Robertson House, Whitefriars Crescent, PERTH on 24 June 2021 Assessor's Appellant's Case No Details & Contact Description & Situation Appellant NAV RV NAV RV Remarks 001 08SKB2786000 SORTING OFFICE ROYAL MAIL GROUP LIMITED £11,900 £11,900 757371 0002 87-93 HIGH STREET 100 VICTORIA EMBANKMENT Update 2019 KINROSS LONDON 31 March 2020 KY13 8AA EC4Y 0HQ 002 12PTR0127000 WAREHOUSE DMS PARTNERS LTD £35,100 £35,100 £17,550 £17,550 719396 0005 UNIT 1A PER ANDREW REILLY ASSOC. LTD Update 2020 ARRAN ROAD 31 RUTLAND SQUARE 12 June 2020 PERTH EDINBURGH PH1 3DZ EH1 2BW 003 12PTR0127125 WAREHOUSE DMS PARTNERS LTD £17,200 £17,200 £8,600 £8,600 524162 0002 UNIT 1B PER ANDREW REILLY ASSOC. LTD Update 2020 ARRAN ROAD 31 RUTLAND SQUARE 12 June 2020 PERTH EDINBURGH PH1 3DZ EH1 2BW 004 12PTR0095000 WAREHOUSE & OFFICE REMBRAND TIMBER LTD £36,900 £36,900 £18,450 £18,450 772904 0003 ARRAN ROAD PER ANDREW REILLY ASSOC. LTD Update 2020 PERTH 31 RUTLAND SQUARE 19 June 2020 PH1 3DZ EDINBURGH EH1 2BW 005 12PTR0127250 WAREHOUSE BELLA & DUKE LTD £30,100 £30,100 522012 0002 UNIT 2 PER ANDREW REILLY ASSOCIATES LTD Update 2020 ARRAN ROAD 31 RUTLAND SQUARE 23 June 2020 PERTH EDINBURGH PH1 3DZ EH1 2BW 006 09SUC0144000 YARD SUEZ RECYCLING & RECOVERY UK LTD £49,800 £49,800 766760 0002 WOOD CHIP PROCESSING PLANT PER AVISON YOUNG Update 2019 BINN HILL 1ST FLOOR, SUTHERLAND HOUSE 29 March 2020 GLENFARG 149 ST VINCENT STREET PERTH GLASGOW PH2 9PX G2 5NW Page 1 Assessor's Appellant's -

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY. C J^-'Chceq ~Ojud Capita 6Jxs$ of Yecurrd§> Ylt £93 J

tw mm* w • •• «•* m«! Bin • \: . v ;#, / (SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY. C J^-'ChceQ ~oJud Capita 6jXS$ Of Yecurrd§> Ylt £93 J SrwlmCj fcomininanotj THE Commissariot IRecorfc of Stirling, REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS 1 607- 1 800. EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S., ROTHESAY HERALD AND LYON CLERK. EDINBURGH : PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY. 1904. EDINBURGH : PRINTED BY JAMES SKINNER AND COMPANY. HfoO PREFACE. The Commissariot of Stirling included the following Parishes in Stirling- shire, viz. : —Airth, Bothkennar, Denny, Dunipace, Falkirk, Gargunnock, Kilsyth, Larbert, part of Lecropt, part of Logie, Muiravonside, Polmont, St. Ninian's, Slamannan, and Stirling; in Clackmannanshire, Alloa, Alva, and Dollar in Muckhart in Clackmannan, ; Kinross-shire, j Fifeshire, Carnock, Saline, and Torryburn. During the Commonwealth, Testa- ments of the Parishes of Baldernock, Buchanan, Killearn, New Kilpatrick, and Campsie are also to be found. The Register of Testaments is contained in twelve volumes, comprising the following periods : — I. i v Preface. Honds of Caution, 1648 to 1820. Inventories, 1641 to 181 7. Latter Wills and Testaments, 1645 to 1705. Deeds, 1622 to 1797. Extract Register Deeds, 1659 to 1805. Protests, 1705 to 1744- Petitions, 1700 to 1827. Processes, 1614 to 1823. Processes of Curatorial Inventories, 1786 to 1823. Miscellaneous Papers, 1 Bundle. When a date is given in brackets it is the actual date of confirmation, the other is the date at which the Testament will be found. When a number in brackets precedes the date it is that of the Testament in the volume. C0mmtssariot Jformrit %\\t d ^tirlitt0. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS, 1607-1800. Abercrombie, Christian, in Carsie.