Micro-Malting for the Quality Evaluation of Rye (Secale Cereale) Genotypes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brewing Grains What Is Malt?

612.724.4514 [email protected] www.aperfectpint.net Brewing Grains Brewing grains are the heart and soul of beer. Next to water they make up the bulk of brewing ingredients. Brewing grains provide the sugars that yeast ferment. They are the primary source of beer color and a major contributor to beer flavor, aroma, and body. Proteins in the grains give structure to beer foam and minerals deliver many of the nutrients essential to yeast growth. By far the most common brewing grain is malted barley or barley malt, but a variety of other grains, both malted and unmalted, are also used including wheat, corn, rice, rye, and oats. What is Malt? To put it plainly, malt is cereal grain that has undergone the malting process. In the simplest terms, malting is the controlled germination and kilning of grain. Malting develops the diastatic enzymes that accomplish the conversion of starch to sugar during brewing and begins a limited process of conversion that makes the starches more accessible to the brewer. Malting also gives brewing grains their distinctive colors and flavors. Only the highest quality grain, called brewing grade, is selected for malting. Brewing grade grain is selected for, among other things, high starch content, uniform kernel size, low nitrogen content, and high diastatic power. Diastatic power is the ability of grains to break down complex starch molecules into simpler sugars for brewing. It is determined by the amount of diastatic enzymes in the grain. Barley is the most commonly malted grain, but other grains like wheat and rye are also malted. -

272 Medals Were Awarded to 240 Breweries

Category 21: American-Belgo-Style Ale - 34 Entries Gold: Tank 7, Boulevard Brewing Co., Kansas City, MO Silver: Dear You, Ratio Beerworks, Denver, CO Bronze: Still Single, Light the Lamp Brewery, Grayslake, IL Category 22: American-Style Sour Ale - 36 Entries Gold: Vice Sans Fruit, Wild Barrel Brewing Co., San Marcos, CA Silver: Mirage, New Terrain Brewing Co., Golden, CO Bronze: Sour IPA, New Belgium Brewing Co., Fort Collins, CO Category 23: Fruited American-Style Sour Ale - 180 Entries Gold: Guava Dreams, Del Cielo Brewing Co., Martinez, CA Silver: Peach Afternoon, Port Brewing Co. / The Lost Abbey, San Marcos, CA 2020 WINNERS LIST Bronze: Summer Sun, Stereo Brewing Co., Placentia, CA Category 24: Brett Beer - 48 Entries Category 1: American-Style Wheat Beer - 59 Entries Gold: Bottle Conditioned Day Drinker, Lost Forty Brewing, Little Rock, AR Gold: Whoopty Whoop Wheat, Wild Ride Brewing, Redmond, OR Silver: Touch of Brett, Alesong Brewing & Blending, Eugene, OR Silver: Emmer, Lost Worlds Brewing, Cornelius, NC Bronze: Saison de Walt, Flix Brewhouse, Carmel, IN Bronze: 10 Barrel TWheat, 10 Barrel Brewing Co. - Bend Pub, Bend, OR Category 25: Mixed-Culture Brett Beer - 74 Entries Category 2: American-Style Fruit Beer - 125 Entries Gold: Wild James, Coldfire Brewing, Eugene, OR Gold: Strawberry Zwickelbier, Twin Sisters Brewing Co., Bellingham, WA Silver: Déluge, Sanitas Brewing Co., Boulder, CO Silver: Everything But The Seeds, 1623 Brewing Co., Eldersburg, MD Bronze: Gathering Red Currants & Peaches, Grimm Artisanal Ales, Brooklyn, -

Mother's North Grille Beer List

Mother's North Grille beer list ¶=Canned beer =Gluten Free ●=Low Cal (sad but true… items are limited & subject to change) ALL DAY Bucket specials ALL DAY pitcher specials 5 domestic bottled beers ($4 below)…………………………………$15.00 64oz Domestic Pitchers…............................................. $12.00 5 craft bottled beers of your choice, ($6 below)……………..$22.00 64oz Craft Beer Pitchers…........................................... $18.00 IPA Stouts & PORTERS Bell's Two Hearted • MI • 7% American IPA…………………………………….$7.00 Breckenridge Oatmeal Stout • CO • 4.95% …………………………….……$6.00 Dogfish 90 Minute IPA • DE • 9% American Double IPA……………………...………………..$8.00 Breckenridge Vanilla Porter • CO • 5.4% …………………………….……$6.00 ¶ Founders All Day IPA • MI • 4.7% American Session IPA……………………...………………..$6.00 DuClaw Sweet Baby Jesus • MD • 6.5% Porter..............................................................$7.00 Southern Tier IPA • NY • 7.3% American IPA………………………………………………..$6.00 Founders Breakfast Stout • MI • 8.3%……………………...………………..$7.00 ¶ Southern Tier Lake Shore Fog • NY • 6.5% NE IPA………………………………………………..$6.00 ¶ Union Snow Pants • MD • 8% English Oatmeal Stout………………………….$7.00 Lager ciders Abita Amber • LA • 4.5% Amber/Red Lager....................................................$5.50 ♥ Austin Eastciders Blood Orange • TX • 5%....................................$6.00 Brooklyn Lager • NY • 5.2% English Pale……………………………………………………….$6.00 ♥ Bold Rock Virginia Apple • VA • 4.7%……………………………………….$5.50 Corona Extra • Mexico • 4.6% Pale Lager…………………………..$5.00 ♥ -

Autochthonous Biological Resources for the Production of Regional Craft Beers: Exploring Possible Contributions of Cereals, Hops, Microbes, and Other Ingredients

foods Review Autochthonous Biological Resources for the Production of Regional Craft Beers: Exploring Possible Contributions of Cereals, Hops, Microbes, and Other Ingredients Nicola De Simone 1 , Pasquale Russo 1, Maria Tufariello 2 , Mariagiovanna Fragasso 1, Michele Solimando 3, Vittorio Capozzi 4,* , Francesco Grieco 2,† and Giuseppe Spano 1,† 1 Department of Agriculture, Food, Natural Science, Engineering, University of Foggia, Via Napoli 25, 71122 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] (N.D.S.); [email protected] (P.R.); [email protected] (M.F.); [email protected] (G.S.) 2 Institute of Sciences of Food Production, National Research Council of Italy (CNR), Via Prov.le Lecce-Monteroni, 73100 Lecce, Italy; [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (F.G.) 3 Rebeers, Microbrewery, Viale degli Artigiani 30, 71121 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] 4 Institute of Sciences of Food Production, National Research Council (CNR), c/o CS-DAT, Via Michele Protano, 71121 Foggia, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] † Both authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Selected biological resources used as raw materials in beer production are important Citation: De Simone, N.; Russo, P.; drivers of innovation and segmentation in the dynamic market of craft beers. Among these resources, Tufariello, M.; Fragasso, M.; local/regional ingredients have several benefits, such as strengthening the connection with territories, Solimando, M.; Capozzi, V.; Grieco, F.; enhancing the added value of the final products, and reducing supply costs and environmental Spano, G. Autochthonous Biological impacts. It is assumed that specific ingredients provide differences in flavours, aromas, and, more Resources for the Production of generally, sensory attributes of the final products. -

BJCP Exam Study Guide

BJCP BEER EXAM STUDY GUIDE Last Revised: December, 2017 Contributing Authors: Original document by Edward Wolfe, Scott Bickham, David Houseman, Ginger Wotring, Dave Sapsis, Peter Garofalo, Chuck Hanning. Revised 2006 by Gordon Strong and Steve Piatz. Revised 2012 by Scott Bickham and Steve Piatz. Revised 2014 by Steve Piatz Revised 2015 by Steve Piatz Revised 2017 by Scott Bickham Copyright © 1998-2017 by the authors and the BJCP CHANGE LOG January-March, 2012: revised to reflect new exam structure, no longer interim May 1, 2012: revised yeast section, corrected T/F question 99 August, 2012: removed redundant styles for question S0, revised the additional readings list, updated the judging procedure to encompass the checkboxes on the score sheet. October 2012: reworded true/false questions 2, 4, 6, 8, 13, 26, 33, 38, 39, 42, and 118. Reworded essay question T15. March 2014: removed the Exam Program description from the document, clarified the wording on question T13. October 2015: revised for the 2015 BJCP Style Guidelines. February, 2016: revised the table for the S0 question to fix typos, removed untested styles. September-October, 2017 (Scott Bickham): moved the BJCP references in Section II.B. to Section I; incorporated a study guide for the online Entrance exam in Section II; amended the rubric for written questions S0, T1, T3, T13 and T15; rewrote the Water question and converted the rubrics for each of the Technical and Brewing Process questions to have three components; simplified the wording of the written exam questions’ added -

Lipid-Protein Interactions in Beer and Beer Foam Brewed with Wheat

Lipid-Protein Interactions in Beer and Beer Foam Brewed with Wheat Flour1 Keith S. Morris, Pall Europe Ltd., Europa House, Havant Street, Portsmouth, POl 3PD England, and James S. Hough, British School of Malting and Brewing, Birmingham University, P.O. Box 363, Birmingham B15 2TT England ABSTRACT under an atmosphere of nitrogen gas there is a significant increase in the extractable bound lipid fraction, which has been shown to be Use of wheat flour as a brewing adjunct has been shown to enhance beer mainly caused by the nonselective binding of triglycerides by foam stability, as measured by the Rudin method, and also to give gluten proteins (1). Subsequent work by Frazier et al (2) involved protection against the adverse effects of added triolein on foam stability. The efficiency of this protective action is dependent on the contact time using radiolabeled triolein to follow the fate of triglycerides during between the lipid and the beer and is specific to triolein. The addition of dough development under nitrogen. A significant proportion of palmitic acid showed different effects on the foam stability of beer brewed the lipid was found to be stably bound to a protein derived from the using wheat flour. This effect was postulated to be caused by the specific acetic acid-soluble fraction of dough. The protein, named ligolin, binding of triolein to proteins derived from wheat flour. Interaction has a molecular weight of approximately 9,000-11,000 daltons and between triolein and beer proteins was identified by precipitation of is speculated to be of fundamental importance in the formation of radiolabeled lipid with trichloroacetic acid. -

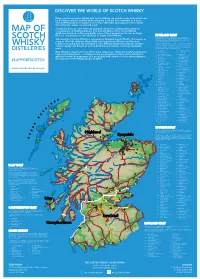

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

July 2002 As Many of You Know, I Will Be Moving to Logan, PRESIDENT: Utah, at the End of This Month to Take a Teaching Royal Willard Position at Utah State University

This is the HOTV Brewsletter EDITOR'S NOTE VOLUME XXII, NUMBER 7 by Kendall Staggs July 2002 As many of you know, I will be moving to Logan, PRESIDENT: Utah, at the end of this month to take a teaching Royal Willard position at Utah State University. I'm excited about (541) 752-1314 the move, but wistful about leaving behind the VICE PRESIDENT: great folks of the Heart of the Valley Homebrew Scott Leonard Club. This will be my last brewsletter as editor, but (541) 752-0780 I hope to contribute some articles down the road. I NEWSLETTER EDITOR: also hope to visit Corvallis in the future, not only to Kendall Staggs see friends, but to find some good beer! Auf (541) 753-6538 Wiedersehen. CLUB TREASURER: Lee Smith In cerevisiae, fortis (In beer there is strength). (541) 926-2286 FESTIVAL DIRECTOR: PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL BEERFEST Joel Rea by Ron Hall (541) 758-1674 The Portland International Beerfest will be held THIS MONTH'S MEETING July 12-14, at a park near the Lloyd Center. You may want to get hotel rooms for the weekend or The Heart of the Valley Homebrew Club meets on coordinate drivers. The Lloyd Center is on the the third Wednesday of each month, alternating MAX line, so you can pretty much stay anywhere between Corvallis and Albany. Our next meeting downtown, as long as you are sober enough to find will be at 7:00 p.m. on July 17, at the home of Scott the train station afterward. I have a room at the and Karen Caul, 2930 NW Mulkey, Corvallis. -

2018 World Beer Cup Style Guidelines

2018 WORLD BEER CUP® COMPETITION STYLE LIST, DESCRIPTIONS AND SPECIFICATIONS Category Name and Number, Subcategory: Name and Letter ...................................................... Page HYBRID/MIXED LAGERS OR ALES .....................................................................................................1 1. American-Style Wheat Beer .............................................................................................1 A. Subcategory: Light American Wheat Beer without Yeast .................................................1 B. Subcategory: Dark American Wheat Beer without Yeast .................................................1 2. American-Style Wheat Beer with Yeast ............................................................................1 A. Subcategory: Light American Wheat Beer with Yeast ......................................................1 B. Subcategory: Dark American Wheat Beer with Yeast ......................................................1 3. Fruit Beer ........................................................................................................................2 4. Fruit Wheat Beer .............................................................................................................2 5. Belgian-Style Fruit Beer....................................................................................................3 6. Pumpkin Beer ..................................................................................................................3 A. Subcategory: Pumpkin/Squash Beer ..............................................................................3 -

The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages

The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages © 2016 Robert A. Freitas Jr. All Rights Reserved. Abstract. Specialized nanofactories will be able to manufacture specific products or classes of products very efficiently and inexpensively. This paper is the first serious scaling study of a nanofactory designed for the manufacture of a specific food product, in this case high-value-per- liter alcoholic beverages. The analysis indicates that a 6-kg desktop appliance called the Fine Spirits Synthesizer, aka. the “Whiskey Machine,” consuming 300 W of power for all atomically precise mechanosynthesis operations, along with a commercially available 59-kg 900 W cryogenic refrigerator, could produce one 750 ml bottle per hour of any fine spirit beverage for which the molecular recipe is precisely known at a manufacturing cost of about $0.36 per bottle, assuming no reduction in the current $0.07/kWh cost for industrial electricity. The appliance’s carbon footprint is a minuscule 0.3 gm CO2 emitted per bottle, more than 1000 times smaller than the 460 gm CO2 per bottle carbon footprint of conventional distillery operations today. The same desktop appliance can intake a tiny physical sample of any fine spirit beverage and produce a complete molecular recipe for that product in ~17 minutes of run time, consuming <25 W of power, at negligible additional cost. Cite as: Robert A. Freitas Jr., “The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages,” IMM Report No. 47, May 2016; http://www.imm.org/Reports/rep047.pdf. 2 Table of Contents 1. -

How to Malt Barley (Or Wheat) for Beer (Or Whisky/Whiskey) I

How to Malt Barley (or Wheat) for Beer (or Whisky/Whiskey) I. Start with Good Quality Barley (or Wheat) A. When purchasing grain for malting, first ask about what types of chemicals might have been used on the grain and then about the grain's history: when it was harvested, how it was stored, etc. B. Inspect the Grain 1. Bits of chaff – and even the occasional dead bug – are quite normal and are of little concern. This sort of debris can easily be removed later when the grain is washed. It will usually float to the surface of the water where it can be skimmed off in a matter of minutes. 2. Grain that has live bugs should generally be avoided, as such bugs will spread to other grain stores and feast on all available grain until it is ready for use. Some of those bugs will also contribute a strong off-smell and off-taste, as well. However, buggy grain can occasionally be had for free, and there are a few types of bugs that do minimal damage to the grain if they are not allowed much time to do their worst. But definitely proceed cautiously with live bugs. 3. The presence of foreign seeds mixed in with the grain may or may not be problematic. A few kernels of corn, a bean or two, a few oats, etc., should not be cause for concern, but if there are unknown seeds mixed in with the grain, ask what they are and act accordingly. 4. Examine the color of the grain and avoid any that has a grayish hue, as this would indicate that the grain was mildewed, either in the field or in storage. -

Undestanding Malting Barley Quality Aaron Macleod, Director, Center for Craft Food and Beverage Hartwick College, Oneonta, NY, 13820 [email protected]

Undestanding Malting Barley Quality Aaron MacLeod, Director, Center for Craft Food and Beverage Hartwick College, Oneonta, NY, 13820 [email protected] Malt is the key ingredient in beer that provides the starch and enzymes necessary to produce the fermentable sugars which yeast then turn into alcohol. Malt also provides the color and flavor compounds which contribute to the final character of beer. Malting is the biological process that turns barley into malt. It is a three stage process including soaking (or steeping) the grain in water to bring the kernels to 45% moisture; germination under cool, humid conditions and drying (or kilning) to dry and stabilize the final malt. Barley must meet strict quality criteria to be acceptable for malt production. Maintaining tight controls on these quality factors in the grain is necessary to ensure good processing efficiency and final product quality in the malthouse and brewery. Care must be taken when growing malting barley to ensure that it meets the necessary specifications. A premium is paid to growers for high quality malting barley to compensate for the extra effort. High quality malting barley should have the following characteristics: Pure lot of an acceptable variety Germination of 95% or higher Protein content raging between 9.5% to 12.5% (dry basis) Moisture content below 13.5% Plump and uniform kernels Free of disease and low DON content Less than 5% of peeled, broken, or damaged kernels Clean and free of insects, admixtures, ergot or foreign material Varietal purity Malting barley varieties are bred specifically for characteristics that promote good malting and brewing performance, such as high enzymatic activity, as well as good agronomic performance and disease resistance.