Cognition All the Way Down

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Collectibles

Unique Record Collectibles 3-9 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in gold vinyl with 7 inch Hound Dog picture sleeve embedded in disc. The idea was Elvis then and now. Records that were 20 years apart molded together. Extremely rare, one of a kind pressing! 4-2, 4-3 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-3 Elvis As Recorded at Madison 3-11 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in black and blue vinyl. Side A has a Square Garden AFL1-4776 Made in blue vinyl with blue or gold labels. picture of Elvis from the Legendary Performer Made in clear vinyl. Side A has a picture Side A and B show various pictures of Elvis Vol. 3 Album. Side B has a picture of Elvis from of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the Aloha playing his guitar. It was nicknamed “Dancing the same album. Extremely limited number from Hawaii album. Side B has a picture Elvis” because Elvis appears to be dancing as of experimental pressings made. of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the same the record is spinning. Very limited number album. Very limited number of experimental of experimental pressings made. Experimental LP's Elvis 4-1 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-8 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 4-10, 4-11 Elvis Today AFL1-1039 Made in blue vinyl. Side A has dancing Elvis Made in gold and clear vinyl. Side A has Made in blue vinyl. Side A has an embedded pictures. Side B has a picture of Elvis. Very a picture of Elvis from the inner sleeve of bonus photo picture of Elvis. -

Federalism All the Way Down

THE SUPREME COURT 2009 TERM FOREWORD: FEDERALISM ALL THE WAY DOWN Heather K. Gerken TABLE OF CONTENTS I. TH E G HOST O F SOVEREIGNTY ......................................................................................... II A. P rocess F ederalists..............................................................................................................14 B . M inding the Gap ........................................................................................................ 18 II. PUSHING FEDERALISM ALL THE WAY DOWN...........................................................21 A. Why Stop w ith States?.................................................................................................. 22 B . Why Stop w ith Cities? .................................................................................................. 23 C . W hat's in a N ame?......................................................................................................... 25 D. Sovereignty and the Neglect of Special Purpose Institutions.................................. 26 E. W idening Federalism's Lens...........................................................................................28 i. The "Apples to Apples" Problem.............................................................................28 2. An Example: Rethinking the Jury...........................................................................30 M. THE POWER OF THE SOVEREIGN VERSUS THE POWER OF THE SERVANT SEPARATION OF POWERS, CHECKS AND BALANCES, AND FEDERALISM.33 A. Federalism -

Name That Song Memorylanetherapy.Com

Name that Song Memorylanetherapy.com Say or sing a few words from the song and let the audience call out the name of the song, encourage them to name the singer as well. It is best to sing the question line to the tune to make it easier to guess the song. When I was just a little girl, I asked my mother what will I be Que Sera Sera - Doris Day You keep saying youv’e got something for me, something you call love but confess? These Boots are Made for Walking - Nancy Sinatra She said I was high class but that was just a lie, she said I was high class but that was just lie Hound Dog - Elvis Presley You know I work all day to get you money to buy you things? It’s Been a Hard Day’s Night - The Beatles I don’t believe you, you’re not the truth. No one could look as good as you, Mercy Pretty woman - Roy Orbison I see trees of green red roses too, I see them bloom for me and you, and I think to myself What a wonderful world - Louis Armstrong There will be love and laughter and peace ever after tomorrow just you wait and see White Cliffs of Dover - Vera Lynn I hear the train a coming its rolling around the bend and I’ve not seen the sunshine since I don’t know when Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash The old home town looks the same, as I step down from the train and there to meet me is my Mama & Papa Green Green Grass of Home - Tom Jones When the moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie That’s Amore - Dean Martin Let’s pretend that were together all alone. -

Kapa'a, Waipouli, Olohena, Wailua and Hanamā'ulu Island of Kaua'i

CULTURAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE KAPA‘A RELIEF ROUTE; KAPA‘A, WAIPOULI, OLOHENA, WAILUA AND HANAMĀ‘ULU ISLAND OF KAUA‘I by K. W. Bushnell, B.A. David Shideler, M.A. and Hallett H. Hammatt, PhD. Prepared for Kimura International by Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i, Inc. May 2004 Acknowledgements ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i wishes to acknowledge, first and foremost, the kūpuna who willingly took the time to be interviewed and graciously shared their mana‘o: Raymond Aiu, Valentine Ako, George Hiyane, Kehaulani Kekua, Beverly Muraoka, Alice Paik, and Walter (Freckles) Smith Jr. Special thanks also go to several individuals who shared information for the completion of this report including Randy Wichman, Isaac Kaiu, Kemamo Hookano, Aletha Kaohi, LaFrance Kapaka-Arboleda, Sabra Kauka, Linda Moriarty, George Mukai, Jo Prigge, Healani Trembath, Martha Yent, Jiro Yukimura, Joanne Yukimura, and Taka Sokei. Interviews were conducted by Tina Bushnell. Background research was carried out by Tina Bushnell, Dr. Vicki Creed and David Shideler. Acknowledgements also go to Mary Requilman of the Kaua‘i Historical Society and the Bishop Museum Archives staff who were helpful in navigating their respective collections for maps and photographs. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of Work............................................................................................................ 1 B. Methods...................................................................................................................... -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

NEW Sacred Heart Song Book .Pages

#35 Ain’t No Grave #34 Live So God Can Use You #25 Alas! and Did My Savior Bleed #54 Lord I’m in Your Care #97 Alleluia, Alleluia, Give Thanks #112 Lord of the Dance #1 Amazing Grace #98 Lord’s Prayer #87 As the Deer #100 Morning Has Broken #56 Away in a Manger #73 My Hope is Built on Nothing Less #12 Be Thou My Vision #105 Nearer, My God, to Thee #91 Blessed Assurance #49 Nothing But the Blood #57 By the Mark #80 O Come O Come Emmanuel #4 Can the Circle be Unbroken #92 O Holy Night #10 Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing #38 O Mary Don’t You Weep #23 Come, Thou Long Expected Jesus #85 Oh Come, Angel Band #3 Down by the Riverside #9 On the Rock Where Moses Stood #2 Down to the River to Pray #61 Palms of Victory #27 Every Humble Knee Must Bow #24 Peace In The Valley #8 Farther Along #71 Praise the Lord! Ye Heavens, Adore Him #83 For the Beauty of the Earth #70 Revive us again #32 Glory, Glory #82 Ride On, King Jesus #77 Go Tell It on the Mountain #55 River of Jordan #30 Great is Thy Faithfulness #63 Rock of Ages Cleft for Me #60 Green Pastures #39 Shall We Gather At The River? #48 Hallelujah #86 Shouting on the Hills of Glory #88 Hallelujah 146 #81 Silent Night #67 Hallelujah Side #104 Simple Gifts #76 Hark the Herald Angels Sing #93 So Glad I’m Here #20 Hold to God’s Unchanging Hand #110 Somebody’s Knocking at Your Door #84 Holy, Holy, Holy #52 Sow 'Em On The Mountain #103 How Can I Keep From Singing? #45 Stand By Me #28 How Great Thou Art #107 Summons #5 I Am a Pilgrim #22 Sweet Hour of Prayer #96 I Am the Bread of Life #14 Swing Low Sweet -

Sweet Adelines International Arranged Music List

Sweet Adelines International Arranged Music List ID# Song Title Arranger I03803 'TIL I HEAR YOU SING (From LOVE NEVER DIES) June Berg I04656 (YOUR LOVE HAS LIFTED ME) HIGHER AND HIGHER Becky Wilkins and Suzanne Wittebort I00008 004 MEDLEY - HOW COULD YOU BELIEVE ME Sylvia Alsbury I00011 005 MEDLEY - LOOK FOR THE SILVER LINING Mary Ann Wydra I00020 011 MEDLEY - SISTERS Dede Nibler I00024 013 MEDLEY - BABY WON'T YOU PLEASE COME HOME* Charlotte Pernert I00027 014 MEDLEY - CANADIAN MEDLEY/CANADA, MY HOME* Joey Minshall I00038 017 MEDLEY - BABY FACE Barbara Bianchi I00045 019 MEDLEY - DIAMONDS - CONTEST VERSION Carolyn Schmidt I00046 019 MEDLEY - DIAMONDS - SHOW VERSION Carolyn Schmidt I02517 028 MEDLEY - I WANT A GIRL Barbara Bianchi I02521 031 MEDLEY - LOW DOWN RYTHYM Barbara NcNeill I00079 037 MEDLEY - PIGALLE Carolyn Schmidt I00083 038 MEDLEY - GOD BLESS THE U.S.A. Mary K. Coffman I00139 064 CHANGES MEDLEY - AFTER YOU'VE GONE* Bev Sellers I00149 068 BABY MEDLEY - BYE BYE BABY Carolyn Schmidt I00151 070 DR. JAZZ/JAZZ HOLIDAY MEDLEY - JAZZ HOLIDAY, Bev Sellers I00156 072 GOODBYE MEDLEY - LIES Jean Shook I00161 074 MEDLEY - MY BOYFRIEND'S BACK/MY GUY Becky Wilkins I00198 086 MEDLEY - BABY LOVE David Wright I00205 089 MEDLEY - LET YOURSELF GO David Briner I00213 098 MEDLEY - YES SIR, THAT'S MY BABY Bev Sellers I00219 101 MEDLEY - SOMEBODY ELSE IS TAKING MY PLACE Dave Briner I00220 102 MEDLEY - TAKE ANOTHER GUESS David Briner I02526 107 MEDLEY - I LOVE A PIANO* Marge Bailey I00228 108 MEDLEY - ANGRY Marge Bailey I00244 112 MEDLEY - IT MIGHT -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

National Finals Competition Junior & Teen - Solos

2021 NATIONAL FINALS COMPETITION JUNIOR & TEEN - SOLOS # Name Division Style Group Size Studio Time 1 Shelter Junior Open Solo Dancezone Thu 12:30 2 Stereotype Teen Open Solo Dancezone Thu 12:32 3 Light Of Seven Junior Contemporary Solo Independent Thu 12:35 4 Dream In Color Junior Lyrical Solo Inspiration Dance Thu 12:38 Academy 5 Ashes Junior Lyrical Solo Dance Arts Centre Thu 12:41 6 Me Against The Junior Jazz Solo Independent Thu 12:43 Music 7 Bola Rebola Teen Open Solo Dance Authority P.A.S. Thu 12:46 8 Hit, Run Teen Open Solo Independent Thu 12:49 9 Violet Teen Musical Theatre Solo Elite Dance of Tulsa Thu 12:52 10 When You Wish Teen Contemporary Solo Theatre Arts Thu 12:54 Upon A Star 11 Lanterns Lit Teen Contemporary Solo Barb's Centre for Thu 12:57 Dance 12 Northside ** Teen Hip Hop Solo Independent Thu 1:00 13 Ho Hey Teen Contemporary Solo Jamie Bragg Signature Thu 1:03 Dance 14 Shifting Forward Teen Contemporary Solo Studio A Dance Center Thu 1:05 15 Promise to Pursue Teen Lyrical Solo Independent Thu 1:08 16 Sorry Teen Lyrical Solo Independent Thu 1:11 17 Woman Up Teen Jazz Solo Unity Dance Studios Thu 1:14 18 All Shook Up Teen Jazz Solo G. Scotten Talent Thu 1:16 Center 19 Work It Teen Jazz Solo The Dance Vault Thu 1:19 20 Big And Loud ** Junior Musical Theatre Solo Dance Force LLC Thu 1:22 21 Finding Wonderland Junior Lyrical Solo Dance Force LLC Thu 1:25 22 We're In The Money Junior Musical Theatre Solo Independent Dance Thu 1:27 Collective LLC 2021 NATIONAL FINALS COMPETITION JUNIOR & TEEN - SOLOS # Name Division Style -

Long Way Down

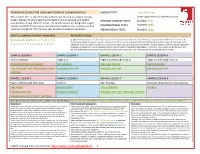

TEACHER RESOURCE FOR LONG WAY DOWN BY JASON REYNOLDS ANCHOR TEXT Long Way Down This resource with its aligned lessons and texts can be used as a tool to increase (Order Copies from CCS Book Warehouse) student mastery of Ohio’s Learning Standards. It should be used with careful SHORTER LITERARY TEXTS Available HERE consideration of your students’ needs. The sample lessons are designed to target specific standards. These may or may not be the standards your students need to INFORMATIONAL TEXTS Available HERE master or strengthen. This resource should not be considered mandatory. MEDIA/VISUAL TEXTS Available HERE OHIO’S LEARNING POWER STANDARDS RESOURCE FOCUS RL. 9-10.1, RL. 9-10.2, RL. 9-10.3, RL.9-10.4, Student learning will focus on the analysis of both informational and poetic texts. Jason Reynold’s Long Way Down will serve as a mentor text. Students will analyze techniques used and draw evidence from several exemplar texts (informational and poetic) to support their mastery of RI. 9-10.1, RI. 9-10.2, RI. 9-10.3, W. 9-10.3 citing text, determining theme/central idea, understanding complex characters/characterization, recognizing the cumulative impact of figurative language and poetic form, and finding connections between ideas introduced and developed in the texts. There will be much time spent with text-dependent questioning, many opportunities for classroom discussions, and a few creative narrative writing opportunities. SAMPLE LESSON 1 SAMPLE LESSON 2 SAMPLE LESSON 3 SAMPLE LESSON 4 Prior to Reading Pages 1-70 Pages 1-192 (through -

Kupugani Camp Songs SLOW JAMS

Kupugani Camp Songs SLOW JAMS.........................................................................2 The Camp Song (tune of “The Cup Song”).........................12 Ain’t Nothing Wrong with Me.................................................2 Don't Drop That Gaga Ball! (“don't drop that thun thun thun”) Goodnight Song....................................................................2 ............................................................................................12 Don’t Laugh at Me.................................................................2 Drivin' Through the Woods (“Forget You” by Cee Lo Green) Make New Friends................................................................3 ............................................................................................12 We will always be..................................................................3 Should Have ... (“When I Was Your Man” by Bruno Mars) . 12 Linger....................................................................................4 BIRTHDAY SONGS............................................................13 Round the Glowing Campfire................................................4 NON-KUPUGANI SPECIFIC SONGS.................................14 As Years Go By.....................................................................4 The Bear Song....................................................................14 Dear Kupugani......................................................................5 Mud song............................................................................15 -

Political Commentary in Black Popular Music from Rhythm and Blues to Early Hip Hop

MESSAGE IN THE MUSIC: POLITICAL COMMENTARY IN BLACK POPULAR MUSIC FROM RHYTHM AND BLUES TO EARLY HIP HOP James B. Stewart "Music is a powerful tool in the form of communication [that] can be used to assist in organizing communities." Gil Scott-Heron (1979) This essay examines the content of political commentaries in the lyrics of Rhythm and Blues (R & B) songs. It utilizes a broad definition of R & B that includes sub-genres such as Funk and "Psychedelic Soul." The investigation is intended, in part, to address persisting misinterpretations of the manner in which R & B influenced listeners' political engagement during the Civil Rights- Black Power Movement. The content of the messages in R & B lyrics is deconstructed to enable a fuller appreciation of how the creativity and imagery associated with the lyrics facilitated listeners' personal and collective political awareness and engagement. The broader objective of the essay is to establish a foundation for understanding the historical precedents and political implications of the music and lyrics of Hip Hop. For present purposes, political commentary is understood to consist of explicit or implicit descriptions or assessments of the social, economic, and political conditions of people of African descent, as well as the forces creating these conditions. These criteria deliberately exclude most R & B compositions because the vast majority of songs in this genre, similar to the Blues, focus on some aspect of male-female relationships.' This is not meant to imply that music examining male-female relationships is devoid of political implications; however, attention is restricted here to lyrics that address directly the relationship of African Americans to the larger American body politic.