Unravelling Bhakra: Assessing the Temple of Resurgent India Report of a Study of the Bhakra Nangal Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Plan 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A. 4055 Capital Outlay on Police

161 13: DETAILED STATEMENT OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE Figures in italics represent charged expenditure Nature of Expenditure Expenditure Expenditure during 2010-11 Expenditure Upto % Increase during 2009-10 Non PlanPlan Total 2010-11 (+) / Decrease (-) State Plan Centrally during the sponsored year Scheme/ Central Plan 1 234 5 6 78 ( ` In lakh) A. Capital Account of General Services- 4055 Capital Outlay on Police- 207 State Police- Construction- Police Station 23,66.57 .. 77,01,30 .. 77,01,30 2,06,37.40 2,25,42 Office Building 21,33.43 .. 13,88.70 .. 13,88.70 98,16,10 -34.91 Other schemes each costing ` five crore and .. .. .. .. .. 76,74.15 .. less Total-207 45,00.00 .. 90,90.00 .. 90,90.00 3,81,27.65 1,02.00 211 Police Housing- Construction- (i) Investment--Investment in Police Housing .. .. .. .. .. 69,82.16 .. Corporation. (ii) Other Old Projects .. .. .. .. .. 5,86.47 .. (iii) Other schemes each costing ` five crore and .. .. .. .. .. 12,30.22 .. less Total-211 .. .. .. .. .. 87,98.85 .. Total-4055 45,00.00 .. 90,90.00 .. 90,90.00 4,69,26.50 1,02.00 4058 Capital Outlay on Stationery and Printing- 103 Government Presses- (i) Machinery and Equipments .. .. .. .. .. 7,23.78 .. (ii) Printing and Stationery 7.49 .. 5.60 .. 5.60 36.94 .. 162 13: DETAILED STATEMENT OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE-contd. Figures in italics represent charged expenditure Nature of Expenditure Expenditure Expenditure during 2010-11 Expenditure Upto % Increase during 2009-10 Non PlanPlan Total 2010-11 (+) / Decrease (-) State Plan Centrally during the sponsored year Scheme/ Central Plan 1 234 5 6 78 ( ` In lakh) A. -

Gazetteers Organisation Revenue Department Haryana Chandigarh (India) 1998

HARYANA DISTRICT GAZETTEEERS ------------------------ REPRINT OF AMBALA DISTRICT GAZETTEER, 1923-24 GAZETTEERS ORGANISATION REVENUE DEPARTMENT HARYANA CHANDIGARH (INDIA) 1998 The Gazetteer was published in 1925 during British regime. 1st Reprint: December, 1998 © GOVERNMENT OF HARYANA Price Rs. Available from: The Controller, Printing and Stationery, Haryana, Chandigarh (India). Printed By : Controller of Printing and Stationery, Government of Haryana, Chandigarh. PREFACE TO REPRINTED EDITION The District Gazetteer is a miniature encyclopaedia and a good guide. It describes all important aspects and features of the district; historical, physical, social, economic and cultural. Officials and other persons desirous of acquainting themselves with the salient features of the district would find a study of the Gazetteer rewarding. It is of immense use for research scholars. The old gazetteers of the State published in the British regime contained very valuable information, which was not wholly reproduced in the revised volume. These gazetteers have gone out of stock and are not easily available. There is a demand for these volumes by research scholars and educationists. As such, the scheme of reprinting of old gazetteers was taken on the initiative of the Hon'ble Chief Minister of Haryana. The Ambala District Gazetteer of 1923-24 was compiled and published under the authority of Punjab Govt. The author mainly based its drafting on the assessment and final reports of the Settlement Officers. The Volume is the reprinted edition of the Ambala District Gazetteer of 1923-24. This is the ninth in the series of reprinted gazetteers of Haryana. Every care has been taken in maintaining the complete originality of the old gazetteer while reprinting. -

4055 Capital Outlay on Police

100 9 STATEMENT NO. 13-DETAILED STATEMENT OF Expenditure Heads(Capital Account) Nature of Expenditure 1 A. Capital Account of General Services- 4055 Capital Outlay on Police- 207 State Police- Construction- Police Station Office Building Schemes each costing Rs.one crore and less Total - 207 211 Police Housing- Construction- (i) Construction of 234 Constables Barracks in Policelines at Faridabad. (ii) Construction of Police Barracks in Police Station at Faridabad. (iii) Construction of Police Houses for Government Employees in General Pool at Hisar. (iv) Construction of Houses of Various Categories for H.A.P. at Madhuban . (v) Investment--Investment in Police Housing Corporation. (vi) Construction of Police Houses at Kurukshetra,Sonepat, and Sirsa. (vii) Other Schemes each costing Rs.one crore and less Total - 211 Total - 4055 4058 Capital Outlay on Stationery and Printing- 103 Government Presses- (i) Machinery and Equipments (ii) Printing and Stationery (iii) Extension of Government Press at Panchkula Total - 103 Total - 4058 4059 Capital Outlay on Public Works- 01 Office Buildings- 051 Construction- (i) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Fatehabad (ii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Jhajjar (iii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Panchkula (iv) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Yamuna Nagar (v) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Kaithal (vi) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Rewari (vii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Faridabad (viii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Bhiwani (ix) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Narnaul (x) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Jind (xi) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Sirsa (xii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Hisar 101 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE DURING AND TO END OF THE YEAR 2008-2009 Expenditure during 2008-2009 Non-Plan Plan Centrally Sponsered Total Expenditure to Schemes(including end of 2008-2009 Central Plan Schemes) 23 4 5 6 (In thousands of rupees) . -

Current Condition of the Yamuna River - an Overview of Flow, Pollution Load and Human Use

Current condition of the Yamuna River - an overview of flow, pollution load and human use Deepshikha Sharma and Arun Kansal, TERI University Introduction Yamuna is the sub-basin of the Ganga river system. Out of the total catchment’s area of 861404 sq km of the Ganga basin, the Yamuna River and its catchment together contribute to a total of 345848 sq. km area which 40.14% of total Ganga River Basin (CPCB, 1980-81; CPCB, 1982-83). It is a large basin covering seven Indian states. The river water is used for both abstractive and in stream uses like irrigation, domestic water supply, industrial etc. It has been subjected to over exploitation, both in quantity and quality. Given that a large population is dependent on the river, it is of significance to preserve its water quality. The river is polluted by both point and non-point sources, where National Capital Territory (NCT) – Delhi is the major contributor, followed by Agra and Mathura. Approximately, 85% of the total pollution is from domestic source. The condition deteriorates further due to significant water abstraction which reduces the dilution capacity of the river. The stretch between Wazirabad barrage and Chambal river confluence is critically polluted and 22km of Delhi stretch is the maximum polluted amongst all. In order to restore the quality of river, the Government of India (GoI) initiated the Yamuna Action Plan (YAP) in the1993and later YAPII in the year 2004 (CPCB, 2006-07). Yamuna river basin River Yamuna (Figure 1) is the largest tributary of the River Ganga. The main stream of the river Yamuna originates from the Yamunotri glacier near Bandar Punch (38o 59' N 78o 27' E) in the Mussourie range of the lower Himalayas at an elevation of about 6320 meter above mean sea level in the district Uttarkashi (Uttranchal). -

On the Brink: Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana By

Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana August 2010 For copies and further information, please contact: PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar, Phase I, Delhi – 110 091, India Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development PEACE Institute Charitable Trust P : 91-11-22719005; E : [email protected]; W: www.peaceinst.org Published by PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar – I, Delhi – 110 091, INDIA Telefax: 91-11-22719005 Email: [email protected] Web: www.peaceinst.org First Edition, August 2010 © PEACE Institute Charitable Trust Funded by Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) under a Sir Dorabji Tata Trust supported Water Governance Project 14-A, Vishnu Digambar Marg, New Delhi – 110 002, INDIA Phone: 91-11-23236440 Email: [email protected] Web: www.watergovernanceindia.org Designed & Printed by: Kriti Communications Disclaimer PEACE Institute Charitable Trust and Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) cannot be held responsible for errors or consequences arising from the use of information contained in this report. All rights reserved. Information contained in this report may be used freely with due acknowledgement. When I am, U r fine. When I am not, U panic ! When I get frail and sick, U care not ? (I – water) – Manoj Misra This publication is a joint effort of: Amita Bhaduri, Bhim, Hardeep Singh, Manoj Misra, Pushp Jain, Prem Prakash Bhardwaj & All participants at the workshop on ‘Water Governance in Yamuna Basin’ held at Panipat (Haryana) on 26 July 2010 On the Brink... Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana i Acknowledgement The roots of this study lie in our research and advocacy work for the river Yamuna under a civil society campaign called ‘Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan’ which has been an ongoing process for the last three and a half years. -

Appendix 2: Lower Sutlej Sub Basin

TA7417-IND Support for the National Action Plan for Climate Change Support to the National Water Mission TA 7417- IND: Support for the National Action Plan on Climate Change Support to the National Water Mission Final Report September 2011 Appendix 2 Lower Sutlej Sub Basin PREPARED FOR Government of India Governments of Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu Asian Development Bank Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC ii Appendix 2 Lower Sutlej Sub Basin Appendix 2 Lower Sutlej Sub Basin Punjab Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC iv Appendix 2 Lower Sutlej Sub Basin Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC v Appendix 2 Lower Sutlej Sub Basin SUMMARY OF ABBREVIATIONS A1B IPCC Climate Change Scenario A1 assumes a world of very rapid economic growth, a global population that peaks in mid-century and rapid introduction of new and more efficient technologies. A1 is divided into three groups that describe alternative directions of technological change: fossil intensive (A1FI), non-fossil energy resources (A1T) and a balance across all sources (A1B). A2 IPCC climate change Scenario A2 describes a very heterogeneous world with high population growth, slow economic development and slow technological change. ADB Asian Development Bank AGTC Agriculture Technocrats Action Committee of Punjab AOGCM Atmosphere Ocean Global Circulation Model APHRODITE Asian Precipitation - Highly-Resolved Observational Data Integration Towards Evaluation of Water Resources - a observed gridded rainfall dataset developed in Japan APN Asian Pacific Network for Global Change Research AR Artificial Recharge AR4 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report AR5 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report AWM Adaptive Water Management B1 IPCC climate change Scenario B1 describes a convergent world, with the same global population as A1, but with more rapid changes in economic structures toward a service and information economy. -

Transboundary River Basin Overview – Indus

0 [Type here] Irrigation in Africa in figures - AQUASTAT Survey - 2016 Transboundary River Basin Overview – Indus Version 2011 Recommended citation: FAO. 2011. AQUASTAT Transboundary River Basins – Indus River Basin. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. -

WATER SECTOR in PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT

IDSA Monograph Series No. 18 April 2013 WATER SECTOR in PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT MEDHA BISHT WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN: POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT | 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 18 April 2013 WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT MEDHA BISHT 2 | MEDHA BISHT Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-17-8 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Monograph are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. First Published: April 2013 Price: Rs. 280/- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Layout & Cover by: Vaijayanti Patankar & Geeta Printed at: M/S A. M. Offsetters A-57, Sector-10, Noida-201 301 (U.P.) Mob: 09810888667 E-mail: [email protected] WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN: POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT | 3 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 6 PART I Chapter One ................................................................. -

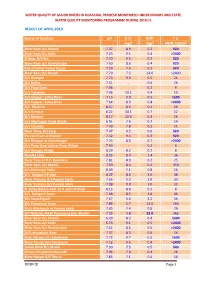

RESULT of APRIL-2010 Name of Location Ph D.O. Mg/L BOD Mg/L T.C

WATER QUALITY OF MAJOR RIVERS IN HIMACHAL PRADESH MONITORED UNDER MINARS AND STATE WATER QUALITY MONITORING PROGRAMME DURING 2010-11 RESULT OF APRIL-2010 Name of location pH D.O. BOD T.C. mg/l mg/l MPN /100ml River Beas U/s Manali 7.37 8.9 0.2 920 River Beas D/s Kullu 7.03 9.1 0.4 >2400 R.Beas, D/s Aut 7.70 9.3 0.3 920 River Beas U/s Pandoh dam 7.60 8.6 0.4 920 Exit of Dehar Power House 7.50 7.5 0.3 920 River Beas D/s Mandi 7.70 7.5 14.0 >2400 D/s Alampur 7.73 9.0 0.5 21 D/s Dehra 7.51 _ 0.6 26 D/s Pong Dam 7.96 _ 0.2 9 U/s Tatapani 7.96 10.1 0.4 10 U/s Slapper, Satluj River 7.15 9.0 0.3 1600 D/s Slapper, Satluj River 7.64 8.9 0.4 >2400 D/s Bhakhra 8.07 8.5 0.2 26 U/s Rampur 8.22 10.1 0.7 12 D/s Rampur 8.17 10.0 0.4 16 U/s Madhopur Head Works 6.91 7.6 0.7 14 U/s Chamba 7.40 7.8 0.3 21 River Sainj, D/s Largi 7.47 9.2 0.6 920 Parvati River at Bhunter 7.32 9.4 0.3 920 D/s Bilaspur at Govindsagar 7.74 8.5 0.7 >2400 U/s Pong Dam Lake at Pong Village 7.93 - 0.2 6 D/s Wangtu Bridge 8.29 8.2 0.2 8 Renuka Lake 8.05 8.0 1.4 36 River Tons at H.P. -

Dams of India.Cdr

eBook IMPORTANT DAMS OF INDIA List of state-wise important dams of India and their respective rivers List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) Dams are an important part of the Static GK under the General Awareness section of Bank and Government exams. In the following eBook, we have provided a state-wise list of all the important Dams in India along with their respective rivers to help you with your Bank and Government exam preparation. Here’s a sample question: In which state is the Koyna Dam located? a. Gujarat b. Maharashtra c. Sikkim d. Himachal Pradesh Answer: B Learning the following eBook might just earn you a brownie point in your next Bank and Government exam. Banking & REGISTER FOR A Government Banking MBA Government Exam 2017 Free All India Test 2 oliveboard www.oliveboard.in List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) LIST OF IMPORTANT DAMS IN INDIA Andhra Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Nagarjuna Sagar Dam (also in Telangana) Krishna Somasila Dam Penna Srisailam Dam (also in Telangana) Krishna Arunachal Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Ranganadi Dam Ranganadi Bihar NAME OF THE DAM 2 RIVER Nagi Dam Nagi Chhattisgarh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Minimata (Hasdeo) Bango Dam Hasdeo Gujarat NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Kadana Dam Mahi Karjan Dam Karjan Sardar Sarover Dam Narmada Ukai Dam Tapi 3 oliveboard www.oliveboard.in List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) Himachal Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Bhakra Dam Sutlej Chamera I Dam Ravi Kishau Dam Tons Koldam Dam Sutlej Nathpa Jhakri Dam Sutlej Pong Dam Beas Jammu & Kashmir NAME -

Annual Report 2004-2005

Annual Report 2004-2005 INTRODUCTION The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) was constituted as Central Board for Prevention and Control of Water Pollution (CBPCWP) on 22nd September, 1974 under the provisions of The Water (Prevention & Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, and later under Water (Prevention & Control of Pollution) Amendment Act 1988 (No. 53 of 1988) its name was amended as Central Pollution Control Board. The main functions of CPCB, as spelt out in The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, and The Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, are: 1. to promote cleanliness of streams and wells in different areas of the States through prevention, control and abatement of water pollution; and, 2. to improve the quality of air and to prevent, control or abate air pollution in the country. The Central Pollution Control Board has been playing a key role in abatement and control of pollution in the country by generating relevant data, providing scientific information, rendering technical inputs for formation of national policies and programmes, training and development of manpower, through activities for promoting awareness at different levels of the Government and Public at large. The Central Board has enlisted the thrust areas requiring immediate attention and assisting government to formulate National Plans and to execute these appropriately. The thrust areas are as below. 1.1 THRUST AREAS OF CENTRAL POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD o Monitoring of National Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Programme (NAMP); o -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 38178-IN PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$400 MILLION TO THE SATL JJ JAL VIDYUT NIGAM TD WITH THE GUARANTEE OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDIA Public Disclosure Authorized FOR RAMPUR HYDROPOWER PROJECT August 15,2007 Sustainable Development Department India Country Management Unit South Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective: April 2007) Currency Unit = India Rupees (Rs.) Rs. 41.5 = US$] FISCAL YEAR April 1 - March31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AAD Advance Against Depreciation MoU Memorandum ofUnderstanding CAG Comptroller and Auditor General MTR Mid Term Review CEA Central Electricity Authority MW Mega Watt CERC Central Electricity Regulatory Commission NGO Non-Governmental Organization co2 Carbon Dioxide NHPC National Hydroelectric Power Corp. cwc Central Water Commission NJHP Nathpa Jhakri Hydroelectric Project/ “Nathpa Jhakri” DPR Detailed Project Report NJPC Nathpa Jhakri Power Corporation DSCR Debt Service Coverage Ratio NO, Nitrogen Oxide EMP Environment Management Plan NPV Net Present Value ERR Economic Rate ofReturn PAPS Project Affected Persons ESIA Environment & Social Impact Assessment PCN Project Concept Note FIRR Financial Internal Rate ofReturn