Joshua Tree Field Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black-Chinned Hummingbird: New to Ontario by Nora M

27 Notes Black-chinned Hummingbird: New to Ontario by Nora M. Mansfield About 1700h, Friday, 25 May 1990, a appear to be black, with the breast warm sunny day, Dr. and Mrs. A.A. and sides darker than the Ruby Sterns of Rideau Ferry, Lanark throats'. There was no crest. I too County Ion the Rideau Waterway, thought it looked larger. about 9 km south of Perth) spotted a I asked Ron Beacock of Perth, a strange hummingbird amongst the sharp-eyed, experienced birdwatcher many Ruby-throated Hummingbirds with remarkable surveillance skills, at their feeders. It appeared to be to come. From 2000h to 2045h, with "larger, with a black head and a bit the light waning, we caught glimpses of a crest". They thought it might be of the bird in the feeder area, but sick or dying as it sat much of the these and the videotaped pictures time without moving, only were not clear enough to give us occasionally sipping from a feeder. what we needed definitively And they noted that the Ruby-throats concerning its colour. We decided to tried to chase it. return the next day to obtain more Dr. Sterns videotaped the strange details which might show whether it hummer. Mrs. Sterns tried to locate was a larger, darker Ruby-throated or an expert to identify it. First she prove that it was another species called the Ottawa Otizen newspaper, such as the Black-chinned but its staff was too busy with the Hummingbird IArchilochus alexandri). Meech Lake Accord affair to help. In that event, we would have to get Next she tried Lynne Thompson of an expert to confirm the the Perth Wildlife Reserve who, identification. -

Evaluation of the Global Decline in the True Shrikes (Family Laniidae)

228 ShortCommunications and Commentaries [Auk, Vol. 111 The Auk 111(1):228-233, 1994 CONSERVATION COMMENTARY Evaluation of the Global Decline in the True Shrikes (Family Laniidae) REUVEN YOSEF t ArchboldBiological Station, P.O. Box2057, Lake Placid, Florida 33852, USA The first International Shrike Symposiumwas held Shrike was found in 1975, and of the Northern Shrike at the Archbold Biological Station, Lake Placid, Flor- in 1982. In Switzerland, these two specieshave offi- ida, from 11-15 January 1993. The symposium was cially been declared extinct. attended by 71 participants from 23 countries(45% In Sweden, Olsson (1993) and Carlson (1993) have North America, 32%Europe, 21% Asia, and 2% Africa). attributed the decline (over 50% between 1970 and The most exciting participation was that of a strong 1990) of the Red-backed Shrike to the destruction and contingent of ornithologists from eastern Europe. In deterioration of suitable habitats. Olsson (1993) ob- this commentary I present the points stressedat the served a large reduction of pastures in the last two Symposiumand illustrate them with severalexamples decades,and considers the Swedish law requiring as presentedby the authors. planting of unused pastures and fallow lands with The Symposiumwas convened to focus attention conifers as unfavorable for shrikes. He also stated that on, evaluate, and possibly recommend methods to nitrogenousand acid-rainpollutants have influenced reverse the worldwide decline of shrike populations. vegetationcomposition and insectpopulations, both Many of the 30 speciesare declining, or have become of which in turn have affected shrikes negatively. In extinct locally. Studies have focused mainly on the the Swedish Bird Population Monitoring Program, five speciesfound closestto placeswhere ornithol- the numbers of Red-backed Shrikes declined from a ogists live: Northern/Great Grey Shrike (Laniusex- high index of 100 in 1975, to a low of 60 in 1981. -

Productivity of Loggerhead Shrikes Nesting in an Urban Interface

Productivity of loggerhead shrikes nesting in an urban interface Clint W. Boal, Tracy S. Estabrook and Adam E. Duerr Abstract Loggerhead shrikes (Lanius ludovicianus) are predatory songbirds that were once common across most of North America. A precipitous decline of loggerhead shrikes in recent years has often been associated with habitat degradation and alteration. Loggerhead shrikes are typically an open country species, and there have been no documentation or descriptions of productivity and habitat use by the species in urban environments. We monitored the productivity and characterized nesting habitat of an urban population of loggerhead shrikes in the city of Tucson, Arizona during the breeding seasons of 1997 and 1998. We documented nesting activity by 23 of 27 shrike pairs in 1997 and by 26 of 35 shrike pairs in 1998. Territory re-occupancy was high (72%) between the 2 years. Loggerhead shrikes in Tucson tended to nest earlier than reported elsewhere, with a mean estimated hatch date of April 20, and earliest hatch date of March 30. There was no difference between years in clutch size (P = 0.313) or brood size (P = 0.196). Nor was there a difference between years in fledglings per successful nest (P = 0.439), but the number of fledglings per nesting attempt was greater in 1997 than 1998 (P = 0.002). Nest suc- cess estimations using the Mayfield method indicated nest success rates of 82% in 1997 and 59% in 1998, with an average of 64%. The between year difference was probably due to nesting failures caused by several days of unseasonable heavy rain in 1998. -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Grey Shrikes Unless Noted Otherwise

Trends in systematics Speciation in shades of grey: Grey Shrike L elegans, while other great grey shrike taxa were left undetermined for the time being. the great grey shrike complex The purpose of this short paper is to present an Sometimes clear-cut species limits are hard to update on geographic variation in the great grey come by. A number of widespread Palearctic spe- shrike complex based on recent genetic studies cies and species complexes display an intricate (Gonzalez et al 2008, Klassert et al 2008, Olsson pattern of geographical (plumage) variation. et al 2010) and to show current implications for Information on patterns of genetic variation can species limits within this complex. Olsson et al be a tremendous help in clarifying relationships (2010) sampled by far the most extensively and between populations but the results are not al- agree with Gonzalez et al (2008) and Klassert et al ways unambiguous. The great grey shrike complex (2008) on the basic structure of the phylogeny. is one such diffcult case. Many may have been Therefore, Olsson et al (2010) is referred to below, surprised to note the treatment of great grey shrikes unless noted otherwise. in the second English edition of the Collins bird guide (Svensson et al 2009) in which two species Results are recognized: Great Grey Shrike Lanius excubi- The recovered mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) tree tor and Iberian Grey Shrike L meridionalis. The lat- (fgure 1) shows a deep split between two large ter now only includes the birds from Iberia and clades, representing up to several million years of south-eastern France. -

Recruitment of Juvenile, Captive-Reared Eastern Loggerhead Shrikes Lanius Ludovicianus Migrans Into the Wild Population in Canada

Recruitment of juvenile, captive-reared eastern loggerhead shrikes Lanius ludovicianus migrans into the wild population in Canada E. L. LAGIOS,K.F.ROBBINS,J.M.LAPIERRE,J.C.STEINER and T . L . I MLAY Abstract High post-release survival, low dispersal and the Falco peregrinus (Tordoff & Redig, 2001) and Mauritius recruitment of captive-reared individuals into the wild kestrel Falco punctatus (Nicoll et al., 2004). Studies inves- population are critical to the success of any reintroduction tigating the reasons for reintroduction success or failure programme. Reintroducing a migratory species poses an have focused typically on post-release dispersal and sur- additional challenge as success also depends on the return vival (Tweed et al., 2003; Lockwood et al., 2005; Parish & of captive-reared individuals to breeding grounds in sub- Sotherton, 2007; Bernardo et al., 2011; Mitchell et al., 2011), sequent years. We investigated the effects of seven hus- which are important factors for successful reintroduction. bandry and management factors on the return rate of However, for migratory species success also depends on the captive-reared eastern loggerhead shrikes Lanius ludovicia- return of captive-reared individuals to breeding grounds nus migrans and documented the recruitment of returning and subsequent recruitment into the wild breeding individuals. During 2004–2010, 564 juveniles were released population (Maxwell & Jamieson, 1997). in Ontario, Canada, as part of a field propagation and re- Although the loggerhead shrike is categorized as Least lease programme and there were 27 confirmed sightings Concern on the IUCN Red List (BirdLife International, of returning birds during 2005–2011. Returning birds were 2012), declines in shrike populations have been reported significantly more likely to have been released in large globally (Yosef, 1994). -

Avian and Bat Screening Analysis and Habitat Characterization

AVIAN AND BAT SCREENING ANALYSIS AND HABITAT CHARACTERIZATION Barr Engineering Company UMore Park Research Wind Turbine Dakota County, Minnesota June 2010 Prepared For: Barr Engineering Company 4700 West 77th St. Minneapolis, MN 55435 Prepared By: 1900 Wazee Street, Suite 200 Denver, Colorado 80202 Phone: (720) 330-7280 Fax: (303) 458-5701 www.nrcdifference.com NRC Project # 0010-0110-01 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Purpose ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Project Location ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 METHODS ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Agency Consultation ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Data Acquisition and Analysis .................................................................................................................................. 2 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ................................................................................................................................. -

Loggerhead Shrike

Loggerhead Shrike Shrike Facts Prairie Songbird with a Meaty Appetite Loggerhead shrikes are migratory songbirds that nest in trees and shrubs but require open grasslands for Their predatory habits foraging. Shrikes are unique predators that impale have earned shrike’s their prey on thorns or barbed wire. They prey on small the nickname “butcher mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and insects. bird”. For nesting, shrikes prefer thorny buffaloberry, willow, Manitoba maple and caragana. They will sometimes return to nest in the same shrub year after year. Katheryn Taylor Loggerhead shrikes thrive on native grasslands with Adult loggerhead shrike - note the patches of trees, shrubs and various grass heights, hooked bill and thick black face mask. which may be encouraged through a sustainable For hunting, shrikes grazing system, thus allowing ranching and shrikes to prefer a mix of grass coexist. heights – some patches of tall grasses Loggerhead shrikes are designated as a species to harbor mice and of Special Concern in Alberta and as Threatened voles and areas of nationally. The population is estimated to be between shorter grasses for 8,000-10,000 pairs in the province, as of 2019 survey hunting insects such as data. grasshoppers. Loggerhead shrikes are susceptible to the loss of native prairie habitats, as well as pesticide use and the loss of wintering habitats. Dave Prescott Lacking the talons of birds of prey, shrikes impale their prey on thorns e and wire. Cycl With grasshoppers and fe other insects making Li up 70% of their diet, shrikes are valuable pest-control agents. Late March - April Mid May Return to breeding grounds Build nest in tall shrubs and from the south and mate. -

Loggerhead Shrike in Tamarisk Tree

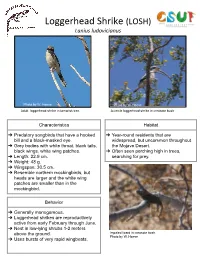

Photo by W. Hoese Photo by W. Hoese Adult loggerhead shrike in tamarisk tree. Juvenile loggerhead shrike in creosote bush Characteristics Habitat ➔ Predatory songbirds that have a hooked ➔ Year-round residents that are bill and a black-masked eye. widespread, but uncommon throughout ➔ Grey bodies with white throat, black tails, the Mojave Desert. black wings, white wing patches. ➔ Often seen perching high in trees, ➔ Length: 22.9 cm. searching for prey. ➔ Weight: 48 g. ➔ Wingspan: 30.5 cm. ➔ Resemble northern mockingbirds, but heads are larger and the white wing patches are smaller than in the mockingbird. Behavior ➔ Generally monogamous. ➔ Loggerhead shrikes are reproductively active from early February through June. ➔ Nest in low-lying shrubs 1-2 meters above the ground. Impaled lizard in creosote bush. Photo by W. Hoese ➔ Uses bursts of very rapid wingbeats. Diet Range ➔ Opportunistic predators that feed primarily on arthropods, lizards and other small vertebrates. ➔ Impale their prey on thorns. ➔ They can kill prey as big as themselves. Zzyzx-specific Information ➔ They can often be seen at the top of tamarisks and poles along Zzyzx Road and near the Desert Studies Center. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Loggerhead_Shrike/maps-range Conservation Status ➔ IUCN status: near threatened. ➔ Populations of loggerhead shrikes are declining nationwide. ➔ The loggerhead shrike in the Mojave may be negatively impacted by competition with the American kestrel, European starling, and common raven. Image source: http://ca.audubon.org/birds-0/loggerhead-shrike Did you know?! ➔ Its gruesome habit of impaling its prey earned the loggerhead shrike the Scorpion impaled on creosote bush branch. Picture by W. -

Loggerhead Shrike Lanius Ludovicianus

Wyoming Species Account Loggerhead Shrike Lanius ludovicianus REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: Migratory Bird USFS R2: Sensitive USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: Sensitive State of Wyoming: Protected Bird CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: Bird of Conservation Concern WGFD: NSS4 (Bc), Tier II WYNDD: G4, S4S5 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern PIF Continental Concern Score: 11 STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS The Wyoming Natural Diversity Database has assigned Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) a state conservation rank ranging from S4 (Apparently Secure) to S5 (Secure) because of uncertainty over extrinsic stressors and population trends of the species in Wyoming. Loggerhead Shrike is classified as Sensitive by Region 2 of the U.S. Forest Service and the Wyoming Bureau of Land Management because of significant range-wide declines from historic levels that may impact the future viability of the species; the cause of the declines are currently unknown 1, 2. Although the species is not classified as Threatened or Endangered, the San Clemente Loggerhead Shrike (L. l. mearnsi) is Endangered throughout its range in California 3. Finally, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources classifies the status of the Loggerhead Shrike as Least Concern 4; however, population trends are decreasing. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: Loggerhead Shrikes, also known as butcherbirds, and Northern Shrikes (L. excubitor) are the only North American species in the family Laniidae. The number and distinctness of subspecies of Loggerhead Shrike varies among reports 5. For the purposes of this document, we follow Yosef (1996) and recognize 9 subspecies. Only L. l. excubitorides is found in Wyoming 6. Description: Loggerhead Shrike is a robin-sized passerine identifiable by its gray back, head, and breast; white chin, throat, and belly; black mask; black primaries and secondaries with a white wing patch; black tail with white outer tail coverts; and small, black, slightly hooked bill 5. -

T-F08AF00110 Final Report

T-F08AF00110 Final Report FINAL PERFORMANCE REPORT South Carolina State Wildlife Grant SC-T-F08AF00110 (T-43) South Carolina Department of Natural Resources October 1, 2008—December 31, 2017 Project Title: Conservation of Migratory Land birds in South Carolina Principal Investigator Amy Tegeler Bird Conservation Coordinator South Carolina Department of Natural Resources 900 Clemson Road, Columbia, SC 29229 [email protected] Objective 1: Coordinate and collaborate with internal and external partners to implement land bird objectives outlined in the CWCS at state and regional scales. Provide avian input into the CWCS update and implement recommendations. [NOTE: The Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) of 2005 was renamed the State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) when it was revised in 2015.] Accomplishments: I. Work within the agency and with partners to develop, implement and fund management, monitoring and research projects to achieve land bird objectives. Assessing the Status of Loggerhead Shrike in South Carolina Participated in the International Loggerhead Shrike Working Group. The goals are to identify limiting factors, quantify genetics of remaining loggerhead shrikes in eastern North America, better understand population demographics, and develop habitat models addressing habitat requirements. To assist with these efforts, developed and funded a graduate project titled “Assessing the status of Loggerhead Shrike in South Carolina” in collaboration with Clemson University. The project evaluated 1) what factors affect loggerhead shrike detectability, 2) how land cover characteristics influence loggerhead shrike occupancy on a landscape and habitat patch scale, and 3) factors influencing Page 1 of 113 T-F08AF00110 Final Report loggerhead shrike nest site selection in South Carolina. -

Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Wildlife List Introduction

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Wildlife List Introduction Established as a national refuge in 1930 by a Presidential Proclamation, the Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge is a haven for a diverse range of wildlife. Most of the refuge’s 37,600 acres are now inundated due to flooding by the Salton Sea. 1785 acres of agricultural fields and freshwater marsh remain manageable. Located 228 feet below sea level, the Salton Sea is one of the lowest places in the United States. The area was created in 1905, when a diversion structure on the Colorado River failed, and the river flowed into the Salton Sink for 16 months. Today, the waters of the Salton Sea have stabilized. The Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge holds the distinction of having An egret chick and egg in their nest. the most diverse array Enjoying the Refuge’s Wildlife The study of wild animals in their natural habitat has become an of bird species found on increasingly popular pastime for many people. Viewing of wildlife any national wildlife can be greatly enhanced by a pair of binoculars or a spotting scope. This equipment allows the wildlife to be refuge in the west. viewed at a distance, thus minimizing disturbance. Also, a good wildlife/ birding guide is helpful in locating Common egrets in the bulrush. ©D.B. Marshall/USFWS and identifying the various species. 3 Enjoying the Refuge’s Birdlife Numbers and species of birds you will see here vary according to season. Heavy migrations of waterfowl, marsh birds, and shorebirds occur during spring and fall.