The Silk Industry in Brianza

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pearl of Lake Como

A B C D E F G H I MAP 1 COMO LOC. RONCHI 1 1 VERGONESE LOC. CRELLA The Pearl of Lake Como LOC. CROTTO VILLA TROTTI S. GIOVANNI 2 P “The most exclusive 2 resort on Lake Como. GUGGIATE So beautiful, so breathtaking, VILLA TRIVULZIO GERLI so comfortable, so unique. MULINI DEL PERLO LOPPIA you’ll feel in heaven. 3 3 VILLA SUIRA MELZI LAGO DI COMO CIVENNA S. PRIMO That’s Bellagio!” MAGREGLIO P ERBA SCEGOLA LIDO TARONICO AUREGGIO CASATE 4 4 P BORGO VISGNOLA P REGATOLA BUS VILLA PARKING P SERBELLONI S. MARTINO VILLA GIULIA PESCALLO PUNTA SPARTIVENTO 5 OLIVERIO 5 S. VITO O ECC LAGO DI LECCO L A B C D E F G H I MAP OF THE CENTRE OF BELLAGIO Boat Terminal Letter Box Imbarcadero Buca delle lettere Car Ferry Terminal Autotraghetto Tourist Office / Ufficio Informazioni Tel. e Fax +39.031.950.204 Bus Terminal Fermata autobus PromoBellagio Office Public toilets Ufficio PromoBellagio Bagni pubblici Tel. e Fax +39.031.951.555 Pharmacy [email protected] Farmacia www.bellagiolakecomo.com T U V W X Y Z GIARDINI DI VILLA MELZI L I D O DI V I A BELLAGIO P . C A R C A N O 1 LAGO 1 LUNGOLA DI COMO R I O EU RO P A P L U N G O L A R IO M A R C O N I CAR FER RY TERMINAL TOURIST OFFICE / UFFICIO INFORMAZIONI BOAT TERMINAL / IMBARCADERO 2 P 2 I MAZZIN PIAZZA A M P O O I O A R I F R E A I F T N D A R A A O I S R N I R U L L V U E NG MANZONI A OLARIO A N A L O C I N R E V M L G O A M P PHARMACY A M C A T PARCO T FARMACIA I I L I C O MUNALE L E I A I A C E N T R A L A V N S N S I O I A A A D A T T T T N ELL A B R BIBLIOTECA ALI ALI ALI ALI G S S S S VIA ER A VIA E. -

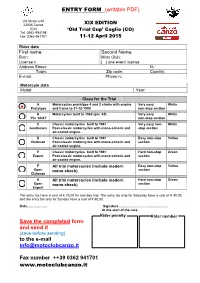

ENTRY FORM (Writable PDF) Save the Completed

ENTRY FORM (writable PDF) Via Meda n.40 22035 Canzo XIX EDITION (Co) ‘Old Trial Cup’ Caglio (CO) Tel. 0362-994198 Fax. 0362-941701 11-12 April 2015 Rider data First name: Second Name: Born: Moto Club: License n. [ ] one event license Address Street: N.: Town: Zip code: Country: E-mail: Phone n.: Motorcyle data Model: Year: Class for the Trial A Motorcycles prototype 4 and 2 stroke with engine Very easy White Prototype and frame to 31-12-1990 non-stop section B Motorcycles built to 1965 (pre ’65) Very easy White Pre ‘65/4T non-stop section C Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Ver y easy non - White Gentlemen Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and stop section air-cooled engine. D Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Easy non -stop Yellow Clubman Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. E Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Hard non -stop Green Expert Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. F All trial motorcycles (include modern Easy non -stop Yellow Open mono shock) section Clubman G All trial motorcycles (include modern Hard non -stop Green Open mono shock) section Expert The entry tax have a cost of € 75,00 for two day trial. The entry tax only for Saturday have a cost of € 40,00 and the entry tax only for Sunday have a cost of € 40,00. Data……………… Signature……………………………………… At the start of the race Rider penalty Rider number Save the completed form and send it (save before sending) to the e-mail [email protected] Fax number ++39 0362 941701 www.motoclubcanzo.it How reach the trial in Caglio (CO) From Turin : Highway Turin-Milan following on the west ring of Milan to direction Venice and exit to Cinisello Balsamo toward the highway Milan-Lecco direction Lecco. -

The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy

The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy RICERCA N°07/2016 Edited by Gruppo Chimici and Centro Studi The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy This Research has been carried out by: Centro Studi and Gruppo Chimici, Assolombarda Confindustria Milano Monza e Brianza Centro Studi, Farmindustria Centro Studi, Federchimica We thank Unioncamere Lombardia for industrial production data Contents 1. FOREWORD 5 2. THE CHEMICAL AND PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY IN LOMBARDY 6 Key figures 6 The size of the industry 9 Industrial production trends between 2007 and the second quarter of 2016 11 The international perspective 12 R&D activities 14 1. Foreword I am very pleased to disclose to you “The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy”. This research is promoted by Gruppo Chimici Assolombarda, a group of firms associated to Assolombarda Confindustria Milano Monza e Brianza currently including about 680 companies and almost 50,000 employees, which I have the honour to represent. The aim is to provide an all-round analysis and work tool, acting as a basis for an industrial policy proposal that recognises the significance of those sectors, both at local and national level. Lombardy is particularly cut out for the Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry, thanks to an efficient network of companies and industrial clients, universities and research centres, plant design companies and advanced services. The Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry means innovation. It stays ahead of the market and lays the basis for future Italian growth. The crisis has not left us unscathed, but the Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry is recovering from the crisis, with Lombardy giving a head start. -

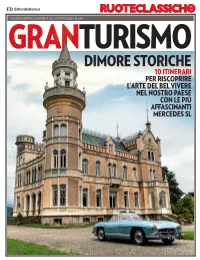

Dimore Storiche

GALLERIA RUOTECLASSICHE N. 122 AGOSTO 2020 - € 4,40 GRANTURISMO DIMORE STORICHE 10 ITINERARI PER RISCOPRIRE GRANTURISMO L’ARTE DEL BEL VIVERE NEL NOSTRO PAESE CON LE PIÙ DIMORE STORICHE AFFASCINANTI MERCEDES SL LAGO DI LECCO SCHEDA ITINERARIO Lunghezza (km) 103 Tempo (ore) 2,45 Strada ✱✱✱✱ QUEL RAMO Panorama ✱✱✱✱ Torri da fiaba Una conformazione DEL LAGO... del tutto originale Dalla Brianza, dove la nobiltà milanese possedeva ville per lo svago in campagna, quella di Villa Lattuada, costruita a metà abbiamo raggiunto Bellagio, esclusiva località lacustre, valicando il Ghisallo, dell’Ottocento per soddisfare il desiderio uno dei passi mitici nella storia del ciclismo. E poi Lecco, ricca di ricordi manzoniani del committente di organizzare feste da Testo di Alessandro Giudice - foto di Alessandro Bianchi ballo ed eventi mondani per i nobili che lì avevano le loro residenze di villeggiatura. 48 49 LAGO DI LECCO Bellagio Introbio Lago di Como Lierna (Lario) Lago di Lecco Ghisallo 4 3 Magreglio Mandello del Lario e l’auto è azzurra, filante, rigorosamente scoperta e molto, RISPETTO ALLA COUPÉ, LA ROADSTER molto esclusiva non può che VANTA UNA MIGLIORE TENUTA sposarsi con un luogo da sogno, romantico e fascinoso. Un DI STRADA: MERITO DEL NUOVO Sconnubio spontaneo quello tra la nostra Mercedes-Benz 300 SLS, il prototipo dal RETROTRENO, MENO SCORBUTICO quale originò nel 1957 la Roadster (erede Canzo della coupé “Ali di gabbiano”), e Villa 5 Lecco Lattuada, stile fiabesco e un destino già Parco scritto nell’idea stessa del suo progetto. Civate Regionale del Monte Barro VOTATA ALLA MONDANITÀ Erba 2 Fu realizzata a fine Ottocento dall’architetto Calolziocorte bresciano Antonio Tagliaferri, che ebbe incarico dal committente, il cavalier Oggiono Francesco Lattuada, imprenditore nel campo della seta, di realizzare una villa Alzate Brianza fuori dall’ordinario, concepita per ospitare feste ed eventi mondani, il tutto senza badare a spese. -

Brambilla's Family

Monza and Brianza with Brambilla’s family Routes, gastronomy, culture and sport www.provincia.mb.it PROVINCIA MONZA BRIANZA www.visitbrianza.it Monza and Brianza with Brambilla’s family Routes, gastronomy, culture and sport www.provincia.mb.it PROVINCIA MONZA BRIANZA www.visitbrianza.it Introduction The guidebook on Monza and the Brianza area proposes routes and itineraries organized by the “Brambilla family” for discover- ing the gastronomical, historical and cultural aspects of a ter- ritory, homeland to small and medium enterprises, which wel- comed and was the birthplace of many famous people, from Leonardo da Vinci to Stendhal, from Alessandro Manzoni to Gi- useppe Parini: the Brianza region. Talking about tourism in Brianza may be considered a challenge, a taboo to overcome. For this reason we are now proposing a new and different approach for getting to know our territory, with an easy-to-use and handy guidebook able to stimulate and give a new lease of life to Brianza’s treasures. Not a didac- tic guidebook, like the many crowding the bookstores, but a tool able to help tourists to discover by themselves what the territory offers, with the aim of making the most of its gems, products and traditions, combining visits, events and sightsee- ing itineraries. Follow the members of the “Brambilla family”’ and, thanks to their heterogeneity, you will get to know the several crown Province of Monza and Brianza jewels that embellish our territory: from cultural resources to Via Napoleone Bonaparte 2 beautiful landscapes, from the major sites of artistic, historic Mombello di Limbiate (MB) and architectural interest to industrial archaeology. -

Luoghi Visitabili 2019 ING

Al pubblico fino a PARTITION OF PLACES BY GEOGRAPHICAL AREA Lecco pag. 5 Lecco pag. 5 The Lake pag. 9 Abbadia Lariana pag. 9 Bellano pag. 9 Colico pag. 10 Dervio pag. 12 Lierna pag. 13 Mandello del Lario pag. 14 Varenna pag. 15 The Brianza area pag. 18 Annone di Brianza pag. 18 Barzanò pag. 19 Bosisio Parini pag. 19 Brivio pag. 20 Bulciago pag. 20 Calco pag. 20 Casatenovo pag. 21 Cassago Brianza pag. 21 Civate pag. 22 River Adda pag. 23 Galbiate pag. 24 Garlate pag. 26 Imbersago pag. 27 Merate pag. 27 Missaglia pag. 29 Montevecchia pag. 30 Monticello Brianza pag. 32 Oggiono pag. 32 Olgiate Molgora pag. 33 Olginate pag. 33 2 Osnago pag. 34 Sirtori pag. 34 Valmadrera pag. 34 Verderio pag. 35 Valsassina, Val d’Esino and Valvarrone pag. 36 Barzio pag. 36 Cortenova pag. 36 Esino Lario pag. 36 Margno – Pian delle Betulle pag. 37 Moggio pag. 37 Morterone pag. 38 Piani Resinelli pag. 38 Premana pag. 38 Primaluna pag. 39 Vestreno pag. 40 Vendrogno pag. 41 Valle San Martino pag. 41 Calolziocorte pag. 41 Carenno pag. 43 Vercurago pag. 43 3 KEY OF SYMBOLS Archaeology: in this category you find museums e archaeological sites Industrial archaeology: in this category you find museums on history of industry and factories. Art : in this category you find art galleries, churches, art museums and villas Culture: in this category you find buildings and other historical and literary constructions Gardens: in this category you find botanical gardens Park/Nature: in this category you find natural parks and ecomuseums Science: in this category you find laboratories, -

Sem-Edx Analysis of an Ancient Stone Statue

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONSERVATION SCIENCE ISSN: 2067-533X Volume 9, Issue 1, January-March 2018: 3-12 www.ijcs.uaic.ro THE USE OF MORTAR TO IMITATE WHITE MARBLE AND OTHER STONES Roberto BUGINI1, Cristina CORTI2, Luisa FOLLI1, Laura RAMPAZZI1,2* 1Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche – Istituto per Conservazione la Valorizzazione dei Beni Culturali, via Cozzi 53, Milano (Italy) 2Dipartimento di Scienza e Alta Tecnologia, Università dell’Insubria, Via Valleggio 9, Como (Italy) Abstract The reproduction of natural stone using different kinds of mortars has always been an important character of the architecture of Lombardy (Italy). Many examples of artificial stone, made of a coating of lime mortar on stone or brick structures, are available from Roman times. At the turn of the 20th century, a new kind of material, based on Portland cement and crushed stone, made possible a quite perfect reproduction of different kinds of stone and the making of complicated decorative elements. The raw materials employed to reproduce white marble and other stones used in Lombard architecture were investigated starting from the ‘Fontana di Camerlata’ (Como, 1936–62). Keywords: Mortar; Artificial stone; Cast stone; Marble; Granite; Calcarenite Introduction The use of a material reproducing the aspect of the stone was already widespread in the Greek world. The high cost of working and transporting a natural material was an important factor that encouraged the combined use of brick and other materials and different kinds of mortar. The reasons leading to use a surrogate instead of a natural stone are well testified by an excerpt of Vasari’s Life of artists, which referred to the construction by the architect Giulio Romano (late 16th century) of the Palazzo Te in Mantua, a city set in the Northern Italian alluvial plain (Pianura Padana) far from any rocky outcrops: «Giulio Romano set his hand to the work [Palazzo Te](...). -

Covid-19 Incidence and Its Main Bionomics Correlations in the Landscape Units of Monza-Brianza Province, Lombardy

J Environ Sci Public Health 2020; 4 (4): 349-366 DOI: 10.26502/jesph.96120106 Research Article Covid-19 Incidence and its Main Bionomics Correlations in the Landscape Units of Monza-Brianza Province, Lombardy Vittorio Ingegnoli ,⃰ Elena Giglio Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Milan, Italy *Corresponding Author: Vittorio Ingegnoli, Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Milan, Italy, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 05 November 2020; Accepted: 11 November 2020; Published: 25 November 2020 Citation: Vittorio Ingegnoli, Elena Giglio. Covid-19 Incidence and its Main Bionomics Correlations in the Landscape Units of Monza-Brianza Province, Lombardy. Journal of Environmental Science and Public Health 4 (2020): 349-366. Abstract relationships, leading to the emergence of an Today both ecology and medicine pursue few ecological upgrading discipline, Landscape systemic characters and few correct interrelations. Bionomics. After the exciting result of the relation between the bionomic functionality (BF) and the mortality rate Following bionomics principles, the territory of (MR) in Monza-Brianza Province (Ingegnoli [1]), the Monza-Brianza was studied in all the 55 curiosity to test the correlation of structure/function municipalities (LU). The correlation of Covid-19 conditions of the same landscape units (LU) even Vs. (incidence %) Vs. the bionomic functionality (BF) Covid-19 incidence was experienced, becoming the resulted evident: at BF = 1.0, Covid-19 = 0.90 %, aims of this work. The necessity to follow a new while at BF = 0.45, Covid-19 = 1.20 %. Other scientific paradigm, shifting from reductionism to parameters, unpredictably, have a weak correlation, as systemic complexity, leads to the emergence of a new urbanization, population age, and agriculture, except life concept, not centered on the organism, but on the the bionomic carrying capacity. -

Birth Service

Punti nascita Co ns ultori familiari ASST LECCO Bellano Via Papa Giovanni XXIII tel. 0341.822126 Calolziocorte Via Bergamo, 8/10 tel. 0341.635013 Casatenovo Via Monte Regio, 15 tel. 039.9231207 FMBBM Monza c/o san Gerardo Hospital via Cernusco Lombardone Via Spluga, 49 tel. 039.9514515 Introbio Località Sceregalli, 8/A tel. 0341.983313 Pergolesi, 33 -20900 Monza Lecco Via Tubi, 43 tel. 0341.482611 039/2332164 Mandello del Lario Via Alpini, 1 tel. 0341.739417 www.fondazionembbm.it Oggiono Via Bachelet, 7 tel. 0341.269741 Olginate Via Cesare Cantù, 3 tel. 0341.653015 Hospital in Desio Via Mazzini, 1 - 20832 Desio It is possible to make an appointment by going directly to the service or by 0362/3831 contacting the telephone numbers. www.asst-monza.it For information, visit the website www.asst-lecco.it Hospital in Carate Brianza Via Mosè Bianchi, 9 20841 Carate Brianza – 0362/9841 www.asst-vimercate.it ASST MONZA Bovisio Masciago Via C. Cantù, 7 - [email protected] Hospital in Vimercate Via Santi Cosma e Damiano, 10 Brugherio Viale Lombardia, 270 - [email protected] 20871 Vimercate – 039/66541 Cesano Maderno Via San Carlo,2 - [email protected] Desio Via U. Foscolo, 24/26 - [email protected] www.asst-vimercate.it Limbiate Via Monte Grappa, 40 [email protected] Monza Via de Amicis,17- [email protected] Hospital in Lecco Monza Via Boito, 2 - [email protected] Via dell’Eremo 9/11 – 23900 Lecco Muggiò Via Dante, 4 - [email protected] 848884422 Nova Via Giussani, 11 - [email protected] www.asst-lecco.it Varedo Via S. -

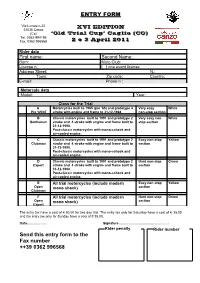

Send This Entry Form to the Fax Number ++39 0362 996568 How Reach the Trial in Caglio (CO)

ENTRY FORM Via Lunate n.22 22035 Canzo XVI EDITION (Co) ‘Old Trial Cup’ Caglio (CO) Tel. 0362-994198 Fax. 0362-996568 2 e 3 April 2011 Rider data First name: Second Name: Born: Moto Club: License n. [ ] one event license Address Street: N.: Town: Zip code: Country: E-mail: Phone n.: Motorcyle data Model: Year: Class for the Trial A Motorcycles built to 1965 (pre ’65) and prototype 4 Very easy White Pre ‘65/4T stroke with engine and frame to 31-12-1968 non-stop section B Classic motorcycles built to 1991 and prototype 2 Very easy non- White Gentlemen stroke and 4 stroke with engine and frame built to stop section 31-12-1990. Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and air-cooled engine. C Classic motorcycles built to 1991 and prototype 2 Easy non-stop Yellow Clubman stroke and 4 stroke with engine and frame built to section 31-12-1990. Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and air-cooled engine. D Classic motorcycles built to 1991 and prototype 2 Hard non-stop Green Expert stroke and 4 stroke with engine and frame built to section 31-12-1990. Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and air-cooled engine. E All trial motorcycles (include modern Easy non-stop Yellow Open mono shock) section Clubman F All trial motorcycles (include modern Hard non-stop Green Open mono shock) section Expert The entry tax have a cost of € 60,00 for two day trial. The entry tax only for Saturday have a cost of € 35,00 and the entry tax only for Sunday have a cost of € 35,00. -

GRUPPO NATURALISTICO DELLA BRIANZA Associazione Per La Difesa Periodico Semestrale Della Natura in Lombardia Anno LI N

Poste Italiane S.p.A. Spedizione in abbonamento postale D.L. 353/2003 (convertito in legge 27/02/04 - N. 46) Art. 1 Comma 2 - DCB COMO GRUPPO NATURALISTICO DELLA BRIANZA Associazione per la difesa Periodico semestrale della Natura in Lombardia Anno LI N. 1 22035 Canzo 2014 Campagna iscrizioni 2014 al Gruppo Naturalistico della Brianza Per iscriversi o rinnovare l’iscrizione al Gruppo per il 2014 effettua al più presto il versamento sul conto corrente postale n° 18854224 intestato al Gruppo Naturalistico della Brianza – C. P. 24 – 22035 Canzo (puoi servirti del bollettino allegato). Come vedete, nonostante gli aumentati costi di gestione dell’Associazione, abbiamo lasciato invariate le quote. Socio ordinario 25 € Socio giovane (fino a 20 anni) 15 € Socio familiare (se convivente) 10 € Socio sostenitore 50 € Socio benemerito da 100 € Adesione speciale G.E.V. 10 € e come sempre FAI DI UN TUO AMICO UN NUOVO SOCIO farai più grande la nostra famiglia e più efficace la nostra azione Anche la sola iscrizione è un contributo per sostenere le nostre campagne per un mondo migliore. Se puoi, partecipa anche alle nostre attività: per informazioni, collaborazione, reclami, rivolgiti alla nuova segrete- ria soci Umberto Guzzi, via Costanza 4, 20095 Cusano Milanino (MI), tel. 02.66401390; [email protected]. AVVISO: ABBONAMENTI OMAGGIO A tutti i destinatari di abbonamenti omaggio che non l’abbiano ancora fatto chiediamo la gentilezza di confermare alla segreteria soci il gradimento della Rivista. Ricordiamo che ai sensi del D. Lgs 30.06.2003, n. 196, le informazioni fornite sono raccolte e trattate per le sole attività del Gruppo Naturalistico della Brianza – ONLUS. -

Publications Office

Official Journal L 162 of the European Union Volume 64 English edition Legislation 10 May 2021 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/756 of 24 March 2021 amending Regulation (EC) No 1234/2008 concerning the examination of variations to the terms of marketing authorisations for medicinal products for human use and veterinary medicinal products (1) . 1 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/757 of 3 May 2021 entering a name in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications ‘Ennstaler Steirerkas’ (PDO) . 4 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/758 of 7 May 2021 on the status of certain products as feed additives within the scope of Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council and on the withdrawal from the market of certain feed additives (1) . 5 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/759 of 7 May 2021 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072 as regards the exceptions from the requirement of a plant passport, the status of Italy, Ireland, Lithuania, Slovenia and Slovakia or certain areas thereof as protected zones, and the reference to a protected zone in Portugal . 18 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/760 of 7 May 2021 amending Implementing Regulations (EU) 2020/761 and (EU) 2020/1988 as regards the management system of some tariff quotas with licences and repealing Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/991 . 25 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/761 of 7 May 2021 amending Annexes I to IV to Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/717 as regards the model forms of zootechnical certificates for breeding animals and their germinal products (1) .