Maternity Care for Women Having a Multiple Birth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton Radiologu Nuchal Translucencey

PATIENT INFORMATION Advice regarding your 12 week scan Nuchal Translucency HAMILTON RADIOLOGY MEDICAL IMAGING SPECIALISTS YOU’RE IN SAFE HANDS A Few Facts . • The vast majority of babies are born normal. • All women, whatever their age, have a small risk of delivering a baby with physical and/or intellectual impairment. • In some cases the impairment is due to a chromosome abnormality such as Downs Syndrome (Trisomy 21). • The programme will only accept foetuses with a crown rump length between 4.5 and 8.3cm ie within the 11+2 days – 13 weeks 6 days period. Optimal time for this scan is 12–13 weeks. • The scan gives an estimate of the risk for Downs Syndrome. To know for sure whether or not the foetus has a chromosomal abnormality, an invasive test is needed (chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis). • However, invasive tests carry a small risk of causing miscarriage (1%). • The early scan allows detection of some, but not all, physical defects. A further scan at 19–20 weeks is recommended. Risk for Downs Syndrome The table to the right shows how the chance of having a baby with Downs Syndrome increases with age. The First Trimester Scan At the 12 week scan we confi rm that the foetus is alive and we assess the gestational age by measuring the crown-rump length. We can look for major physical defects, measure nuchal translucency thickness and calculate your baby’s chance of Downs Syndrome based on the scan fi ndings and your age. Occasionally the foetus is not well seen on the abdominal scan and it may be necessary to perform a transvaginal scan. -

Monoamniotic Twins: What Should Be the Optimal Antenatal Management?

Monoamniotic Twins: What Should Be the Optimal Antenatal Management? Ashis K. Sau1, Kate Langford1, Catherine Elliott1, Lin L. Su2, and Darryl J. Maxwell1 1Fetal Medicine Unit, St.Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK 2National University Hospital, Singapore onoamniotic twinning is a rare event with an incidence of London with a high proportion of socially deprived and M1% of all monozygotic twins and associated with a high black, Asian or mixed race peoples. Management protocols fetal morbidity and mortality. Confident early diagnosis is possi- ble, but optimal management is not yet established. This article employed were those of early detection of chorionicity and presents the experience of a single centre in managing all amnionicity, 2-weekly serial ultrasound surveillance and monoamniotic twins diagnosed during 1994–2000. Seven pairs early delivery by elective cesarean section at around 32 of monoamniotic twins were identified for analysis. All were weeks gestation. From 1997, a formal twin ultrasound sur- managed in accord with a unit protocol that involved early diag- veillance clinic was established and first trimester nuchal nosis, serial ultrasound examination and elective early delivery. In four cases, the detection of monoamnionicity was made translucency screening was performed. The same fetal med- during a first trimester nuchal scan. Discordance for structural icine consultant had clinical input into the management of abnormality was found in three cases where the co-twin was all cases. A summary of the cases can be seen in Table 1. normal. Cord entanglement was detected antenatally in four cases. Two pairs of twins died before 20 weeks. One of these Case 1 had early onset twin–twin transfusion syndrome. -

Screening for Trisomy 21 in Denmark; Evaluation of the Current and Possible Future Strategies

Faculty of Health Sciences University of Copenhagen Screening for trisomy 21 in Denmark; Evaluation of the current and possible future strategies PhD thesis Charlotte Kvist Ekelund Academic supervisors Ann Tabor, professor, DMSc, Department of Fetal Medicine, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen Olav Bjørn Petersen, PhD, consultant, Department of Obstetrics, Aarhus University Hospital Ida Vogel, DMSc, Head of Department of Clinical Genetics, Aarhus University Hospital Evaluation committee Katja Bilardo, Professor, Head Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands Michael Christiansen, Head of Molecular Diagnostics, Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen Lone Krebs, DMSc, Associate professor, consultant, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Holbæk Sygehus, University of Copenhagen The PhD defence will take place Friday the 13th of April 2012, Auditorium B, Teilum, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen. Acknowledgement This thesis was made possible by help from a number of fantastic supervisors and colleagues. First and foremost, I owe my deepest thanks to Professor Ann Tabor. Thank you for sharing your interest and knowledge in first trimester screening with me, for your professional and personal guidance, for always having time and for showing your confidence in me from the very beginning of the project. Your constructive and focused attitude is admirable and to me you have been an extremely inspiring mentor within all aspects of life. I am greatly indebted to Olav Bjørn Petersen, MD, PhD, one of the most enthusiastic and optimistic persons I know. Your positive attitude, support and encouragement have really helped me through the challenging phases of the project. And my sincere thanks to Ida Vogel, MD, DMSc for taking part in the project, for everything you taught me many years ago and for still being there. -

Antenatal Care: Timetable

Antenatal care: timetable NICE issued guidelines on routine care for the healthy pregnant woman in March 2008. They recommend: 10 antenatal visits in the first pregnancy if uncomplicated 7 antenatal visits in subsequent pregnancies if uncomplicated women do not need to be seen by a consultant if the pregnancy is uncomplicated Gestation Purpose of visit 8 - 12 weeks (ideally < 10 Booking visit weeks) general information e.g. diet, alcohol, smoking, folic acid, vitamin D, antenatal classes BP, urine dipstick, check BMI Booking bloods/urine FBC, blood group, rhesus status, red cell alloantibodies, haemoglobinopathies hepatitis B, syphilis, rubella HIV test is offered to all women urine culture to detect asymptomatic bacteriuria 10 - 13 weeks Early scan to confirm dates, exclude multiple pregnancy 11 - 13+6 weeks Down's syndrome screening including nuchal scan 16 weeks Information on the anomaly and the blood results. If Hb < 11 g/dl consider iron Routine care: BP and urine dipstick 18 - 20+6 weeks Anomaly scan 25 weeks (only if primip) Routine care: BP, urine dipstick, symphysis-fundal height (SFH) 28 weeks Routine care: BP, urine dipstick, SFH Second screen for anaemia and atypical red cell alloantibodies. If Hb < 10.5 g/dl consider iron First dose of anti-D prophylaxis to rhesus negative women 31 weeks (only if primip) Routine care as above 34 weeks Routine care as above Second dose of anti-D prophylaxis to rhesus negative women Information on labour and birth plan 36 weeks Routine care as above Check presentation - offer external cephalic version if indicated Information on breast feeding, vitamin K, 'baby-blues' 38 weeks Routine care as above 40 weeks (only if primip) Routine care as above Discussion about options for prolonged pregnancy 41 weeks Routine care as above Discuss labour plans and possibility of induction 1 Prescribing in pregnant patients Very few drugs are known to be completely safe in pregnancy. -

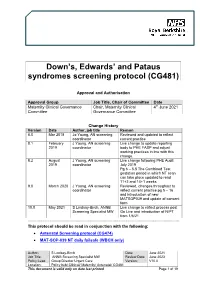

Downs, Edwards & Pataus Screening Protocol (CG481)

Down’s, Edwards’ and Pataus syndromes screening protocol (CG481) Approval and Authorisation Approval Group Job Title, Chair of Committee Date Maternity Clinical Governance Chair, Maternity Clinical 4th June 2021 Committee Governance Committee Change History Version Date Author, job title Reason 8.0 Mar 2018 Jo Young, AN screening Reviewed and updated to reflect coordinator current practice 8.1 February J Young, AN screening Live change to update reporting 2019 coordinator body to PHE FASP and adjust working practices in line with this change. 8.2 August J Young, AN screening Live change following PHE Audit 2019 coordinator July 2019 Pg 6 – 5.5 The Combined Test gestation period in which NT scan can take place updated to read 11+2 and 14+1 weeks 9.0 March 2020 J Young, AN screening Reviewed, changes throughout to coordinator reflect current practice pg 5 – 16 and introduction of new MATSOP039 and update of consent form 10.0 May 2021 S Lindsay-Birch, ANNB Live change to reflect process post Screening Specialist MW Go Live and introduction of NIPT from 1/6/21 ................................................................................................................................................................... This protocol should be read in conjunction with the following: • Antenatal Screening protocol (CG474) • MAT-SOP-039 NT daily failsafe (WBCH only) Author: S Lindsay-Birch Date: June 2021 Job Title: ANNB Screening Specialist MW Review Date: June 2023 Policy Lead: Group Director Urgent Care Version: V10.0 Location: Policy hub/ Clinical/ Maternity/ Antenatal/ CG481 This document is valid only on date last printed Page 1 of 19 Maternity guidelines – Downs, Edwards & Pataus syndromes screening protocol (CG481) June 2021 Contents 1.0 Purpose ............................................................. -

The Effect of Progesterone Use in the First Trimester on Fetal Nuchal Translucency

Original Investigation 29 The effect of progesterone use in the first trimester on fetal nuchal translucency Müberra Namlı Kalem1, Ziya Kalem2, Batuhan Bakırarar3, Ali Ergün1, Timur Gürgan2 1Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Liv Hospital, Ankara, Turkey 2Gürgan Clinic IVF and Women Health Center, Ankara, Turkey 3Department of Biostatistic, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey Abstract Objective: To evaluate the possible association between progesterone use in the first trimester of pregnancy and fetal nuchal translucency (NT). Material and Methods: This is an observational case-control study, which was conducted with patients who underwent nuchal scans between March 2015 and February 2016 and consequently delivered live and healthy babies. The study group was composed of assisted reproductive technology pregnancies and used intravaginal progesterone 180 mg/day until gestational week 12. The control group comprised pregnant women who became pregnant spontaneously without using any progesterone preparation in the first trimester. Results: One hundred sixty-four (57.5%) of 285 patients were in the control group and 121 (42.5%) were in the progesterone group. Age, bodyweight, gravidity, and parity number of previous births and abortus, gestational week, crown-rump lengths, free β-human chorionic gonadotropin, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, and NT values of the progesterone and control groups were recorded and we investigated whether there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of these parameters; maternal weight was found to be higher in the progesterone group than in the control group and the difference between the groups was statistically significant (p=0.019 and p=0.025). -

The Identification and Validation of Neural Tube Defects in the General Practice Research Database

THE IDENTIFICATION AND VALIDATION OF NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS IN THE GENERAL PRACTICE RESEARCH DATABASE Scott T. Devine A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Public Health (Epidemiology). Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by Advisor: Suzanne West Reader: Elizabeth Andrews Reader: Patricia Tennis Reader: John Thorp Reader: Andrew Olshan © 2007 Scott T Devine ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - ii- ABSTRACT Scott T. Devine The Identification And Validation Of Neural Tube Defects In The General Practice Research Database (Under the direction of Dr. Suzanne West) Background: Our objectives were to develop an algorithm for the identification of pregnancies in the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) that could be used to study birth outcomes and pregnancy and to determine if the GPRD could be used to identify cases of neural tube defects (NTDs). Methods: We constructed a pregnancy identification algorithm to identify pregnancies in 15 to 45 year old women between January 1, 1987 and September 14, 2004. The algorithm was evaluated for accuracy through a series of alternate analyses and reviews of electronic records. We then created electronic case definitions of anencephaly, encephalocele, meningocele and spina bifida and used them to identify potential NTD cases. We validated cases by querying general practitioners (GPs) via questionnaire. Results: We analyzed 98,922,326 records from 980,474 individuals and identified 255,400 women who had a total of 374,878 pregnancies. There were 271,613 full-term live births, 2,106 pre- or post-term births, 1,191 multi-fetus deliveries, 55,614 spontaneous abortions or miscarriages, 43,264 elective terminations, 7 stillbirths in combination with a live birth, and 1,083 stillbirths or fetal deaths. -

|||FREE||| Obstetrics and Gynecology

OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY FREE DOWNLOAD Charles R. B. Beckmann,William N.P. Herbert,Douglas W. Laube,Frank Ling,Roger P. Smith | 528 pages | 21 Mar 2013 | Lippincott Williams and Wilkins | 9781451144314 | English | Philadelphia, United States Register for a free account We are grateful for the outstanding care she has provided to our patients. Connect with us on social media! August Learn how and when to remove this template message. Read more. Our providers recommend these 6 helpful tips for reducing your period pain. I haven't seen someone like that in a long time and it was such a Obstetrics and Gynecology surprise. Call us or email us with any questions or to schedule your visit. Chorionic villus sampling Amniocentesis Triple test Quad test Fetoscopy Fetal scalp blood testing Fetal scalp stimulation test Percutaneous umbilical cord blood sampling Apt test Kleihauer—Betke test Lung maturity Lecithin—sphingomyelin ratio Lamellar body count Fetal fibronectin test. Get Obstetrics and Gynecology touch. Wellness and Integrative Care. From pre-conception Now Accepting New Patients Schedule an appointment today. I was in and out in the shortest time possible. Some procedures may include: [8]. Your Partner For a Lifetime of Care. Experienced OB-GYN professionals can seek certifications in sub-specialty areas, including maternal and fetal medicine. You can rest easy knowing that one of our physicians is always on call, 24 hours a day, to deliver your baby. Are you accepting new patients? Imaging Obstetric ultrasonography Nuchal scan Anomaly scan Fetal movement counting Contraction stress test Nonstress test Vibroacoustic stimulation Biophysical profile Amniotic fluid index Umbilical artery dopplers. -

Maternity Services Guideline Antenatal Appointments

MATERNITY SERVICES GUIDELINE ANTENATAL APPOINTMENTS GUIDELINE Version Authors Michala Little - Community Midwifery Manager Kath Chapman – Community Midwifery Team Leader Lynda Fairclough - Community Midwifery Team Leader Owner Michala Little Community Midwifery Manager Date of First issue 1994 Version 12.1 Date of Version issue September 2019 Ratified by York: Obs & Gynae Clinical Scarborough: Obs & Gynae Governance Forum Clinical Governance Forum Date Ratified 12.11.19 12.11.19 Review date September 2021 Version information Significant changes to previous version. Update September 2019 to include aspirin changes, VTE update, proteinurea guidance and safeguarding info Antenatal Appointment Guideline Version No. 12.1 November 2019 – September 2021 Page 1 of 30 Contents Section Title Page 1 Introduction & Scope 3 2 Management 3 2.1 The Booking Process 3 2.2 Criteria for Midwifery Led Care 3 2.3 Criteria for Consultant Review 4 2.4 Criteria for Planned Homebirth 5 2.5 Booking Risk Assessment 6 2.6 Frequency of A/N Visits for Low Risk Women 10 3 Links with 17 4 References 17 Appendices Appendix 1: Referral Flowchart from M/W led Care to Consultant 19 Appendix 2: Procedure for Women Who Attend Antenatal or a Community Clinic without Handheld Pregnancy Records 20 Appendix 3: Procedure for women who do not attend appointments(DNA) 21 Appendix 4: Procedure for women who decline blood products 22 Appendix 5: Procedure for Measuring Symphsis-Fundal Height 23 Appendix 6: High incidence of TB by country 24 Appendix7: Northern and Yorkshire Cleft Lip and Palate service 25 Appendix 8: Flowchart for women recommended to take low dose aspirin 26 Appendix 9: Ante natal payments pathway 27 Appendix 10: Screening for domestic abuse in pregnancy 29 Appendix 11: Pathway of care for women having blood taken for grouping and Antibody Screening’ guideline 30 Antenatal Appointment Guideline Version No. -

Monoamniotic Twins: What Should Be the Optimal Antenatal Management?

Monoamniotic Twins: What Should Be the Optimal Antenatal Management? Ashis K. Sau1, Kate Langford1, Catherine Elliott1, Lin L. Su2, and Darryl J. Maxwell1 1Fetal Medicine Unit, St.Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK 2National University Hospital, Singapore onoamniotic twinning is a rare event with an incidence of London with a high proportion of socially deprived and M1% of all monozygotic twins and associated with a high black, Asian or mixed race peoples. Management protocols fetal morbidity and mortality. Confident early diagnosis is possi- ble, but optimal management is not yet established. This article employed were those of early detection of chorionicity and presents the experience of a single centre in managing all amnionicity, 2-weekly serial ultrasound surveillance and monoamniotic twins diagnosed during 1994–2000. Seven pairs early delivery by elective cesarean section at around 32 of monoamniotic twins were identified for analysis. All were weeks gestation. From 1997, a formal twin ultrasound sur- managed in accord with a unit protocol that involved early diag- veillance clinic was established and first trimester nuchal nosis, serial ultrasound examination and elective early delivery. In four cases, the detection of monoamnionicity was made translucency screening was performed. The same fetal med- during a first trimester nuchal scan. Discordance for structural icine consultant had clinical input into the management of abnormality was found in three cases where the co-twin was all cases. A summary of the cases can be seen in Table 1. normal. Cord entanglement was detected antenatally in four cases. Two pairs of twins died before 20 weeks. One of these Case 1 had early onset twin–twin transfusion syndrome. -

Can We Detect Congenital Abnormalities Earlier in Pregnancy

The Quality and Safety Challenge 2012 Improving quality and safety in maternity services: can we improve prevention, detection and management of congenital abnormalities in pregnancy? Professor Cindy Farquhar, Nicola Arroll, Dr Lynn Sadler, Professor Peter Stone & Vicki Masson PMMRC National Coordinator Services and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Auckland i Acknowledgements We are grateful to the following groups and individuals for their assistance in the production of this report. • The Quality and Safety Challenge 2012 for providing the funding for the project. • The lead maternity carers, general practitioners and District Health Board staff for providing the additional information. • The ultrasound service providers, for supplying the ultrasound images. • PMMRC national coordination service for providing guidance and assistance for collecting the additional data. • Senior sonographer Jenny Mitchell who contributed her time and knowledge. • Dr Sue Belgrave, Dr Tom Gentles and Dr Nicola Austin who undertook the peer review of the report. Author contributions • Professor Cindy Farquhar conceived and supervised the audit and provided revision of the report. • Nicola Arroll collected and assembled the data, contributed to the data analysis and drafting and editing of the report. • Dr Lynn Sadler was involved in the design of the study, provided analysis and interpretation of the data as well as revision of the report. • Professor Peter Stone provided interpretation of the data and made contributions to the report. • Vicki Masson was involved in the conception and design of the study and made contributions to and revised the report. i Executive summary and recommendations The Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee (PMMRC) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on all perinatal deaths with a view to reducing these deaths. -

Prenatal First Trimester Assessment of the Heart

Research Article Annals of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine Published: 15 Jun, 2017 Prenatal First Trimester Assessment of the Heart Cara Monica, Tudorache Stefania, Dimieru Roxana, Florea Maria, Patru Ciprian and Iliescu Dominic* Prenatal Diagnostic Unit, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Craiova, Romania Abstract An efficient first trimester cardiac scan offers the possibility to terminate earlier, safer, and with less economic and emotional costs the pregnancy in cases where major fetal abnormalities are detected. FT anomaly scan was initially offered to high-risk groups and selected population, but because many CHD were found in low risk population, many authors agreed to screen all pregnancies for CHD. It was stated that two-dimensional ultrasound, performed on a standardized protocol, is feasible and repeatable within and between observers in visualizing the normal heart structures as early as 11-13.6 GW. In terms of detection rate of major CHD, recent reports have advocated a percentage of 80-90% when an extended standardized heart screening protocol is used. Nevertheless, this detection rate can vary depending of several factors such as the protocol used, studied population (high or low-risk), scan route (transvaginal, transabdominal or both), definition and prevalence of major congenital heart disease (CHD). CHD early markers, as increased nuchal translucency, abnormal tricuspid and ductus venosus flowsare important indicators for further fetal echocardiographic investigation, as early as possible. Despite the significant impact of the first trimester screening on pregnancies with major congenital heart diseases, we should not underestimate the value of the second trimester fetal anomaly scan, as some cardiac abnormalities are undetectable early in the first trimester, or the expression of the anomaly may be minimal.