A Collective Study of Four of Buffalo, New York's Early Monuments, 1882-1907 Drew C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECC Board of Trustees

ECC Board of Trustees Executive Summary Date: December 13, 2018 Subcommittee: Consent Agenda Agenda Item: Agreement for Consultant Services requested between SUNY Erie and the Buffalo Public Schools for the New York State Pathways in Technology-3 (P-Tech-3) BESOLAR grant program to align with the college’s Computer and Electronics Technology A.A.S. degree program This item is: For Board's Approval Backup Documentation: Attached to this document Background Information: The Buffalo Public School system was awarded funding through the New York State Education Department’s P-Tech BESOLAR grant program. From Fall 2016 through Fall 2021, each year a new freshman cohort at South Park High School begins in the grant. Starting in grade 10, each cohort begins taking SUNY Erie Advanced Studies courses at South Park. The P-Tech grant covers the cost of student tuition outside of the contract. This contract will cover costs associated with tours and student visits to SUNY Erie, curriculum development and SUNY Erie faculty and staff partner visits for the period August 1, 2018 through June 30, 2019. Reasons for Recommendation: Students will have the opportunity to earn SUNY Erie credits through taking course work aligned with the Computer and Electronics Technology A.A.S. degree program. This will facilitate a pipeline of students to matriculate into this degree program at the college. P-Tech grants are awarded throughout New York State through the Department of Education. Fiscal Implications: As the consultant, SUNY Erie will receive up to $9,950. Consequences of Negative Action: Inability to meet grant outcomes. -

Xavier F. Salomon Appointed Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator of the Frick Collection

XAVIER F. SALOMON APPOINTED PETER JAY SHARP CHIEF CURATOR OF THE FRICK COLLECTION Xavier F. Salomon has been appointed to the position of Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator of The Frick Collection, taking up the post in January of 2014. Dr. Salomon―who has organized exhibitions and published most particularly in the areas of Italian and Spanish art of the sixteenth through eighteenth century―comes to The Frick Collection from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he is a curator in the Department of European Paintings. Previously, he was the Arturo and Holly Melosi Chief Curator of Dulwich Picture Gallery, London. Salomon’s two overall fields of expertise are the painter Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) and the collecting and patronage of cardinals in Rome during the early seventeenth century. Born in Rome, and raised in Italy and the United Kingdom, Salomon received his Ph.D. from the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. A widely published author, essayist, and reviewer, Salomon sits on the Consultative Committee of The Burlington Magazine and is a member of the International Scientific Committee of Storia dell’Arte. Comments Frick Director Ian Wardropper, “We are thrilled to welcome Salomon to the post of Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator. He is a remarkable scholar of great breadth and vitality, evidenced by his résumé, on which you will find names as far ranging as Veronese, Titian, Carracci, Guido Reni, Van Dyck, Claude Lorrain, Poussin, Tiepolo, Lucian Freud, Cy Twombly, and David Hockney. At the same time, he brings to us significant depth in the schools of painting at the core of our Old Master holdings, and he will complement superbly the esteemed members of our curatorial team. -

3.1901 Buffalo Endurance Run.2.Pdf

The Morrisania Court fined David W. Bishop Jr. $10 after he was arrested for exceeding the 15 miles per hour speed limit. This was the very reason that the endurance run committee created a maximum 15 miles per hour speed as most municipalities at that time posted 15 miles per hour speed limits, or less! Photo from the September 18, 1901 issue of Horseless Age magazine. Stage One was dusty with deep and bumpy sandy ruts once the contestants departed New York City. The route was difficult to follow. In one village the speed limit was 4 miles per hour. Some hills were difficult to climb and then the downhill run the cars “frequently exceeded 25 miles per hour!” At the closing of the Poughkeepsie control at 9:30 PM seventy-five of the eighty starters had arrived. For stage Two the weather was good but the roads “varying from good to bad and treacherous.” Sixty-five vehicles arrived in Albany within the time limit. Wednesday September 11 the automobiles had to “slacken their speed” due to wet roads in the morning and heavy rain in the afternoon. All the vehicles “skidded to the point of danger.” 51 vehicles reached Herkimer before 9:40, the time of closing the control. Stage Four on Thursday September 12th was another day of rain. The “roads were mostly miserable in the morning with only a few fair stretches.” Tire and axle failure at this point of the endurance run was high. 48 vehicles arrived at the Syracuse closing of the control at 9:30 PM. -

The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1966 The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777 Bernard Mason State University of New York at Binghamton Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Mason, Bernard, "The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777" (1966). United States History. 66. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/66 The 'l(qpd to Independence This page intentionally left blank THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE The 'R!_,volutionary ~ovement in :J{£w rork, 1773-1777~ By BERNARD MASON University of Kentucky Press-Lexington 1966 Copyright © 1967 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS) LEXINGTON FoR PERMISSION to quote material from the books noted below, the author is grateful to these publishers: Charles Scribner's Sons, for Father Knickerbocker Rebels by Thomas J. Wertenbaker. Copyright 1948 by Charles Scribner's Sons. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., for John Jay by Frank Monaghan. Copyright 1935 by the Bobbs-Merrill Com pany, Inc., renewed 1962 by Frank Monaghan. The Regents of the University of Wisconsin, for The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York J 17 60- 1776) by Carl L. Becker, published by the University of Wisconsin Press. Copyright 1909 by the Regents of the University of Wisconsin. -

HISTORIC RESOURCE PROJECT ASSESSMENT St

HISTORIC RESOURCE PROJECT ASSESSMENT St. James Park Capital Vision and Performing Arts Pavilion Project San José, Santa Clara County, California Prepared for: Department of Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services City of San José 200 East Santa Clara St. San José, CA 95113 C/o David J. Powers & Associates, Inc. 04.05.2019 (revised 08.12.2019) ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE, LLC PO Box 1332 San José, CA 95109-1332 St. James Park Historic Resource Project Assessment Table of Contents Table of Contents HISTORIC RESOURCE PROJECT ASSESSMENT ...................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Description...................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose and Methodology of this Study ..................................................................................... 6 Previous Surveys and Historical Status ...................................................................................... 6 Location Map .............................................................................................................................. 8 Summary of Findings ................................................................................................................. -

The Queen C Ity

A Regional Action Plan for Downtown Buffalo Volume 1 – Overview Hub The Context for Decision Making The Queen City Anthony M. Masiello, MAYOR WWW. CITY- BUFFALO. COM November 2003 Downtown Buffalo 2002! DEDICATION To people everywhere who love Buffalo, NY and continue to make it an even better place to live life well. Program Sponsors: Funding for the Downtown Buffalo 2002! program and The Queen City Hub: Regional Action Plan for Downtown Buffalo was provided by four foundations and the City of Buffalo and supported by substantial in-kind services from the University at Buffalo, School of Architecture and Planning’s Urban Design Project and Buffalo Place Inc. Foundations: The John R. Oishei Foundation, The Margaret L. Wendt Foundation, The Baird Foundation, The Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo City of Buffalo: Buffalo Urban Renewal Agency Published by the City of Buffalo WWW. CITY- BUFFALO. COM October 2003 A Regional Action Plan for Downtown Buffalo Hub Volume 1 – Overview The Context for Decision Making The Queen City Anthony M. Masiello, MAYOR WWW. CITY- BUFFALO. COM October 2003 Downtown Buffalo 2002! The Queen City Hub Buffalo is both “the city of no illusions” and the Queen City of the Great Lakes. The Queen City Hub Regional Action Plan accepts the tension between these two assertions as it strives to achieve its practical ideals. The Queen City Hub: A Regional Action Plan for Downtown Buffalo is the product of continuing concerted civic effort on the part of Buffalonians to improve the Volume I – Overview, The Context for center of their city. The effort was led by the Decision Making is for general distribution Office of Strategic Planning in the City of and provides a specific context for decisions Buffalo, the planning staff at Buffalo Place about Downtown development. -

CONGRESSIONAL Recoltd-HOUSE. DECEMBER 3

. 2 CONGRESSIONAL RECOltD-HOUSE. DECEMBER 3, .Ma.ssa;chusetts-Henry L. Dawes and George F. Hoar. ARKANSAS. Clifton R. Breckinridge. John H. Rogers. JJ!ichigan-Omar D. Conger and Thomas W. Palmer. Poindexter Dunn. Samuel W. Peel. Minnesota-Samuel J. R. McMillan and Dwight 1\I. Sabin. James K. Jones. Mi.ssissippi=-James z. George and Lucius Q. C. Lamar. CALIFORNIA. Missouri-Francis M. Cockrell and George G. Vest. Charles A. Sumner. James H. Budd. John R. Glascock. Barclay Henley. Nebraska-Charles F. l\Ianderson and Charles H. VanWyck. WilliamS. Rosecrans. Pleasant B. Tully. Nevada-James G. Fair. New Hampshire-Henry W. Blair and Austin F. Pike. COLORADO. New Jersey-John R. McPherson and William J. Sewell. James B. Belford. New York-Elbridge G. Lapham and Warner Miller. CONNECTICUT. North Carolina-Matt. W. Ransom and Zebulon B. Vance. William W. Eaton. John T. Wait. Ohio-George H. Pendleton and John Sherman. Charles L. 1\fit.<Jhell. Edward W. Seymour. Oregon-Joseph N. Dolph and James H. Slater. DEL.AW .ARE. Pennsylvmtia-J ohn I. Mitchell. Charles B. Lore. Rhode Jslan~Nelson W. Aldrich. FLORIDA.. Sottth Camlina-M. C. Butler ~d Wade Hampton. Robert H. M. Davidson. Horatio Bisbee, jr. Tennessee-Isham G. Harris and Howell E. Jaekson. GEORGIA. Texas-Richard Coke and Sam. Bell Maxey. Thomas Hardeman. James H. Blount. Vermont-George F. Edmunds and Justin S. Morrill. John C. Nicholls. Judson C. Clements. Virginia-William .Mahone and Harrison H. Riddleberger. · Henry G. Turner. Seaborn Reese. N. Charles F. Crisp. Allen D. Candler. West Virginia-Johnson Camden and John E. -

Student Impact

SUMMER 2018 NONPROFIT ORGANIZATION US POSTAGE 80 NEW SCOTLAND AVENUE PAID ALBANY, NEW YORK 12208-3494 PERMIT #161 ALBANY, NY 2018 REUNION SEPT. 20-22, 2018 VISIT THE NEW ALUMNI WEBSITE AT: ALUMNI.ALBANYLAW.EDU • VIEW UPCOMING PROGRAMS AND EVENTS • READ ALUMNI NEWS, SPOTLIGHTS, AND CLASS NOTES • SEARCH FOR CLASSMATES AND COLLEAGUES • UPDATE YOUR CONTACT INFORMATION STUDENT IMPACT ALSO SUMMER 2018 A DEGREE FOR ALBANY LAW SCHOOL’S ALEXANDER HAMILTON FIRST 50 YEARS 2017-2018 ALBANY LAW SCHOOL BOARD OF TRUSTEES CHAIR J. Kevin McCarthy, Esq. ’90 Mary Ann Cody, Esq. ’83 James E. Hacker, Esq. ’84 New York, NY Ocean Ridge, FL Albany, N.Y. David E. McCraw, Esq. ’92 Barbara D. Cottrell, Esq. ’84 New York, NY Hudson, NY SAVE THE DATE! VICE CHAIR Daniel P. Nolan, Esq. ’78 Donald D. DeAngelis, Esq. ’60 Debra F. Treyz, Esq. ’77 Albany, NY Delmar, NY Charleston, SC SEPTEMBER 20–22 Timothy D. O’Hara, Esq. ’96 Jonathan P. Harvey, Esq. ’66 SECRETARY Saratoga Springs, NY Albany, NY • Innovative New Reunion Programming Dan S. Grossman, Esq. ’78 Dianne R. Phillips, Esq. ’88 James E. Kelly, Esq. ’83 New York, NY Boston, MA Germantown, NY • Building Upon Established Traditions TREASURER Rory J. Radding, Esq. ’75 Stephen M. Kiernan, Esq. ’62 New York, NY Marco Island, FL Dale M. Thuillez, Esq. ’72 • Celebrating the Classes Ending in 3’s & 8’s Albany, NY Earl T. Redding, Esq. ’03 Hon. Bernard J. Malone, Jr. ’72 Albany, NY Delmar, NY MEMBERS Hon. Christina L. Ryba ’01 Matthew H. Mataraso, Esq. ’58 Jeanine Arden-Ornt, Esq. -

Imprisoned Art, Complex Patronage

Imprisoned Art, Complex Patronage www.sarpress.sarweb.org Copyrighted Material Figure 4. “The young men, Prisoners, taken to Florida,” Saint Augustine, Florida, 1875. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 1004474. 2 ❖ Copyrighted Material ❖ CHAPTER ONE ❖ The Southern Plains Wars, Fort Marion, and Representational Art Drawings by Zotom and Howling Wolf, the one a Kiowa Indian and the other a South- ern Cheyenne, are histories of a place and time of creation—Fort Marion, Florida, in the 1870s. These two men were among seventy-two Southern Plains Indian warriors and chiefs selected for incarceration at Fort Marion, in Saint Augustine, at the end of the Southern Plains wars. Among the Cheyenne prisoners was a woman who had fought as a warrior; the wife and young daughter of one of the Comanche men also went to Florida, but not as prisoners. During their three years in exile, Zotom, Howling Wolf, and many of the other younger men made pictures narrating incidents of life on the Great Plains, their journey to Florida, and life at Fort Marion. The drawings explored in this book also have a history subsequent to their creation, a history connected to the patron of the drawings and her ownership of them. Other audiences who have seen and studied Zotom’s and Howling Wolf’s drawings are part of the works’ continuing histories, too. Plains Indian drawings and paintings, including works created by men imprisoned at Fort Marion, were visual narratives, intended to tell stories. Those stories still live, for history is, simply put, composed of stories about the past. -

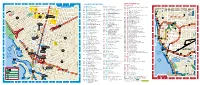

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 a B C D E F G H I J 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 a B C D E F G H I J 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 a B C D E F

ABCDEFGHIJ DOWNTOWN BUFFALO CITY OF BUFFALO Accommodations DOWNTOWN BUFFALO Accommodations F-4 4@ Irish Classical Theatre ABCDEF B-3 bHotel Henry Urban Resort & Conference Center D-7 b Adam’s Mark Buffalo A-8 4# John Maynard Plaque Attractions 1 1 E-2 c Best Western on the Avenue A-1 4$ Kavinoky Theatre (D’Youville College) C-5 cAfrican-American Cultural Center/ E-9 D Buffalo Marriott HarborCenter C-1 4% Kleinhans Music Hall/Buffalo 1 1 Paul Robeson Theatre E-9 e Courtyard by Marriott Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra C-3 d Albright-Knox Art Gallery Downtown/Canalside 4^ E-7 LAFAYETTE BREWING CO. C-5 e Art Dialogue Gallery E-5 f CURTISS BOUTIQUE HoteL E-6 4& Lafayette Square f 2 2 g 4* C-5 Benjamin & Dr. Edward Cofeld Judaic Museum H-2 Doubletree Club Hotel by Hilton D-10 Make Sail Time of Temple Beth Zion 2 2 D-5 h Embassy Suites Buffalo 4( E-7 gBuffalo Central Terminal G-6 Michigan Street Baptist Church h D-5 i Hampton Inn & Suites G-6 5) Nash House Museum F-7 Buffalo Fire Historical Museum C-10 i Buffalo Downtown D-4 5! New Phoenix Theatre on the Park Buffalo Harbor State Park j B-3 j Buffalo History Museum E-6 Hilton Garden Inn Buffalo Downtown D-6 5@ Niagara Square 3 3 D-5 1)Buffalo Museum of Science F-4 1) Hostel Buffalo Niagara 5# 3 3 E-2 Pausa Art House C-8 1!Buffalo RiverWorks F-7 1! HoteL @ THE LAFAYette 5$ 1@ 1@ D-8 PEARL STREET GRILL & D-3 Buffalo Zoo E-5 Hyatt Regency Buffalo BrewerY B-3 1# Burchfield Penney Art Center D-7 1# LoFTS ON PEARL F-4 5% Road Less Traveled Productions C-8 1$Elevator Alley Kayak E-4 1$ Buffalo -

Mtmmmmtm of Buffalo, NY

BUFFALO & ERIE COUJVTT PUBLIC LIBRARY cr. I BUFFALO & ERIE COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY Epf/lfl ELI AS HOWE SEWING MACHINES 1867. 1867. FAMIZT AJV2) MJUYZTFACTUZIIJVG. POINTS OZ" SUPERIORITY i ADJUSTABLE PRESSER FOOT. ADJUSTABLE HEAD. SIMPLICITY: OF MECHANISM. Self-Adjustable Take Up. EASE OF OPERATION. RANGE OF WORK. DURABILITY. PERFECTION OF TENSIONS. THE HOWE, or LOCK-STITCH, IS UNEQUALED. "With every Machine we furnish free a Hemrner, Fellor, Braider, Quilter, Guage, 1 doz. Needles, 6 Bobbins, 2 Wrenches, 1 Oiler, 2 Screw Drivers, Bottle of Oil and Instruction Book. IFXXTTXraTGh 3DEI>-AJRT3^E2SrT. Constantly on hand and for sale, wholesale and retail, the best quality of Machine Twist, Sewing Silk, Cotton and Linen Thread of all sizes and colors, Tuckers, Corders, Kufflers, Machine Findings, Needles, Oil, &c., &c Also, at Wholesale and Retail, the Celebrated WILLISTON'S COMBED SEA ISLAND THREAD for Family and Manufacturing uses. J". 3ST. DORE,IS <Sc CO., OFFICE AND SALESROOM; 18 West Swan Street, Buffalo. Agents Wanted. GROVER & [BAKER'S IMPBOVBD Shuttles Lock Stitch SEWING MACHINES. SMiniMiMiMlXiMOtlXlCi^lMMlU'KUOirHl1 THE ATTENTION OP Tailors, Manufacturers of Clothing, Boots and Shoes, Harnesses, Carriage Trimmings, and all others who require The Best and Most Effective Look Stitch MachinJ Is invited to the above. The Lock Stitch Machines which have been employed in these^ branches of manufacture, have been defective in several essential par ticulars. They have been much too noisy and too much encumbered with cog-wheels or gearing, and wire springs.) to be simple, durable and comfortable in use. In Grover & Baker's Improved Machines these defects have been entirely removed. -

Exploring the Gilded Age of Sculpture Length of Lesson 1-3 Class Grade Levels 9-12 Lesson Type (Pre/During/Post) Pre/During Visit And/Post

United Arts’ Arts and Culture Access Grant Organization name The Albin Polasek Museum & Sculpture Gardens Lesson title Exploring the Gilded Age of Sculpture Length of lesson 1-3 class Grade levels 9-12 Lesson type (pre/during/post) Pre/during visit and/post Objectives Students will visually evaluate the works of art found in the Polasek Historic Home and apply the Gilded Age concepts they have learned to understand which works fall into this aesthetic movement and historical time period. They will then create drawings based on this new knowledge and conduct research on their own. To prepare for your visit, we suggest you review the following vocabulary terms and opt to further engage students with a post activity. Next Generation Sunshine State Standards (NGSSS) VA.912.C.1.1- Integrate curiosity, range of interests, attentiveness, complexity, and artistic intention in the art-making process to demonstrate self-expression. VA.912.C.1.6- Identify rationale for aesthetic choices in recording visual media. VA.912.C.2.4- Classify artworks, using accurate art vocabulary and knowledge of art history to identify and categorize movements, styles, techniques, and materials. VA.912.C.3.3- Examine relationships among social, historical, literary, and/or other references to explain how they are assimilated into artworks. VA.912.C.3.5- Make connections between timelines in other content areas and timelines in the visual arts. VA.912.H.1.3- Examine the significance placed on art forms over time by various groups or cultures compared to current views on aesthetics. Common Core State Standards (CCSS) NA Key vocabulary and definitions Gilded Age - historical time period: The Gilded Age is defined as the time between the Civil War and World War I during which the U.S.