The Problem of Lethytep (Pelynt) and Stress in Cornish Place-Names Oliver Padel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

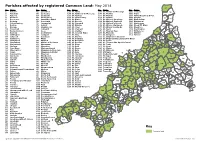

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Meeting Minutes August 2019

PELYNT PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES Minutes of meeting of Pelynt Parish Council held in the Village Hall on Thursday 29th August 2019 MINUTES Action PRESENT Cllr K Wakeham Cllr W E R Philp Cllr E Gibbs Cllr C Puckey Cllr P Evans Cllr S Smith Cllr J R Philp Cllr A Taylor Cllr C Beall Cllr J Nyman Cllr R Pugh Twelve members of the public were also in attendance. 1) 23687 APOLOGIES PCSO S Cocks. 2) 23688 DECLARATION OF INTEREST IN ITEMS ON THE AGENDA None. 3) 23689 MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING The minutes of the Parish Council meeting held on the 25th July 2019 were signed off as a true record. Proposed Cllr E Gibbs. Seconded Cllr P Evans. All agreed. 4) 23690 MATTERS ARISING a) Linden Homes Signs – It was confirmed that the signs have been removed from Summerlane Park. b) Parked Vehicles – The clerk reported the white van at Luffman Close to Cornwall Council as SORN and it will be investigated by the Public Protection Team. PCSO Cocks stated that the other two vehicles were not parked illegally and no action can be taken. c) Churchyard Benches – The clerk stated that both benches in the open churchyard are privately owned and maintained. d) Highways Scheme – It was confirmed the proposal of yellow lining in the area of Wilton Terrace/West End has been removed from the scheme. e) The Green Car Park Closure – It was noted that the annual closure had successfully taken place on the 1st July 2019. 5) 23691 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION The Police report was read stating that during the month of July fifteen crimes had been committed in the Parish. -

CORNWALL. [ KELL1 D VOLUNTEERS

7 .. 180 LISKEARD • CORNWALL. [ KELL1 d VOLUNTEERS. PLACES OF WORSHIP, with times of services. znd Volunteer Battalion Duke of Cornwall's Light In Parish Church (St. Martin), Rev. James Norris M.A. fantry (A. Co. ), Drill hall, Market buildings; ~Iajor vicar; II a.m. & 6.30 p.m. ; wed. 7 p.m. ; fri. II a.m William Sargent, commander; Surgeon-Capt. "\Yilliam Chapel of Ease, Dobwalls, 3 p.m Nettle, medical officer; Color-SPrgt. Edmund Dust, St. :Neot's Catholic, "\Vest street, Rev. Norbert Woolfrey, instructor priest; holy communion, 8.30 a.m. & prayers & mass, LISKEARD UNION. II a.m. ; devotions, instruction & benediction, 6.30 p.m.; holidays of obligation, holy communion & mass, Beard day, alternate saturdays at 1.30 p.m. at the Board 9 a.m. ; thurs .. benediction, 7.30 p.m. ; daily mass, room, Workhouse. 8 a.m The Union, formed January x6th, 1837, comprises the Friends' Meeting House, Pound street ; II a.m. & 6 p.m. ; following places, viz. :-Boconnoc, Broadoak, Calling thurs. II a.m · ton, St. Cleer, St. Dominck, Duloe, St. Ive, St. Keyne, Baptist, Dean street, Rev. George Frederic Payn; II a.m. Lanreath, Lansallos, Lanteglos, Linkinhorne, Liskeard & 6 p.m.; thurs. 7-30 p.m borough & parish, East Looe, West Looe, St. Martin's Bible Christian, Dobwalls; II a.m. & 3 & 6 p.m by-Looe, Menheniot, Morval, St. Neot, Pelynt, St. Bible Christian, Barn street, Rev. Wm. John Smeeth; Pinnock, Southill, Talland & St. Veep. The popula· II a.m. & 6 p.m.; tues. thurs. & fri. 7.30 p.m tion of the union in I8gi was 26,448; area, Io7,441 Bible Christian, Trewidland, 3 & 6 p.m :1cres; rateable value in I897, £123,133 Primitive Methodist, Castle hill, Rev. -

Local Plan 2012 Part 2.Indd

Pre-submission document March 2013 Objectives Objective 4 – Housing PP15 Liskeard and Looe Balance the housing stock to provide a 18.1 Specifi c objectives to be addressed range of accommodation, particularly Community Network Area in planning for the Liskeard and Looe for open market family homes and Community Network Area include: intermediate aff ordable housing in Objective 1 – Economy and Jobs Liskeard. Introduction Deliver economic growth / Objective 5 - Leisure Facilities 18.0 The Liskeard and Looe Community Network Area covers the parishes employment, providing much needed Improve and maintain the provision of of Deviock, Duloe, Dobwalls and Trewidland, Lanreath, Lansallos, Lanteglos, jobs to counterbalance current and recreational, cultural and leisure services Liskeard, Looe, Menheniot, Morval, Pelynt, Quethiock, St Cleer, St Keyne, future housing development in and on and facilities in Liskeard with particular St Neot, St Martin-by-Looe, St Pinnock and Warleggan. the edge of Liskeard. focus on delivering sports pitches. Objective 2 – Sustainable Key Facts: Development Development Strategy Improve connectivity within and on the 18.2 A comprehensive and co- Population 2007: 33,000 edge of Liskeard to ensure the town ordinated approach will be pursued Dwellings 2010: 15,547 (6.1% Cornwall) functions eff ectively as a major hub to the planning and development and service centre for the network area; of Liskeard. The approach set out in Past housing build rates 1991-2010: 1,869 including enhanced public transport the Liskeard Town -

Bosula Bosula Pelynt, Looe, PL13 2LY Pelynt 1.5 Miles Looe 3 Miles Saltash 18 Miles

Bosula Bosula Pelynt, Looe, PL13 2LY Pelynt 1.5 miles Looe 3 miles Saltash 18 miles • Immaculate 4/5 Bed Home • Stunning Rural Location Just Outside Polperro • Separate Really Useful Annexe • Parking, Carport and Garage • Secluded Rural Valley Guide price £535,000 SITUATION Located in a sleepy rural valley, Bosula offers a peaceful haven set within rolling fields of Cornish countryside and yet only two miles from the centre of the popular Cornish fishing village of Polperro. Surrounded by wildlife, Bosula is a real ornithologists dream with over 50 varieties of birds visiting the garden. This attractive home represents a fine lifestyle investment with the rare combination of peace and quiet and with easy access to a most attractive stretch of coastline, yet with easy access to the arterial A38 and the maritime port of Plymouth. Located between the picturesque fishing villages of Polperro and Looe, with their An immaculate 4/5 bed house in a rural valley with separate annexe thriving coastal communities and busy harbours, both are home to a small fishing fleet. There is a choice of south facing sandy beaches, the nearest of which is at just outside the Cornish coastal village of Polperro. Talland Bay with plenty of rock pools to explore. There are numerous beautiful walks in the area including one of the prettiest stretches of the South West Coast Path. Golf courses will be found at Whitsand Bay, Looe and St Mellion. DESCRIPTION Built in 1957 and recently improved and refurbished to fairly exacting standards this spacious detached home enjoys a sunny aspect with views over the gardens and the enclosing valley. -

SN 6738 - Cornwall Census Returns, 1851

this document has been created by the History Data Service (HDS) SN 6738 - Cornwall Census Returns, 1851 This study contains a complete transcript of the Cornwall returns of the census of 1851. Using microfiche loaned to the project by the LDS, volunteers, recruited online transcribed the pages of the enumerators’ books for the Cornwall 1851 census. Other volunteers checked the data using Free Census software. Finally, the organiser validated the data, using yet another piece of Free Census software. The data was collected in 1851. The raw data was in the form of microfiche, organised in accordance with the PRO regulations. Copyright is held by the Crown and TNA confirmed that publishing the transcripts online is allowed. Variables: Field Field name Explanation A civil_parish B eccl_district Ecclesiastical District C ed Edition D folio Folio number E page Page number F schd Schedule number G house House Number H address I x [Blank field] J surname K forenames L x [Blank field] M rel Relationship N c Marital status: M = married, S = separated, U = unmarried, W = widowed O sex P age Q x [Blank field] R occupation S e Employment status T x [Blank field] U chp County or country of birth, see annex for coding V place_of_birth W x [Blank field] X alt Alternative transcription of "chp" where this is unclear in original Y alt_place [Blank field] Z dis Disability AA l Language AB notes Additional remarks Geographical coverage (spelling in the spreadsheets may differ; some of the parishes became part of Devonshire after 1851): Table Coverage (Civil -

Polperro and Lansallos Parish

POLPERRO AND LANSALLOS PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018-2030 CONSULTATION STATEMENT Draft v7 – 08/06/2018 1 CONTENTS 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Designated Area for the Polperro and Lansallos Parish Neighbourhood Development Plan.............4 3 Context................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 Legislative Requirements............................................................................................................................................... 6 5 Consultation Timeline...................................................................................................................................................... 7 6 Consultation Process...................................................................................................................................................... 13 7 Consultation Results...................................................................................................................................................... 17 8 Consultation & Publicity Materials........................................................................................................................... 22 9 Draft NDP Pre-submission Communication........................................................................................................ -

Lanteglos by Fowey Parish Council

LANTEGLOS-BY-FOWEY PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE FULL COUNCIL MEETING HELD IN THE WHITECROSS VILLAGE HALL TUESDAY, 22nd JANUARY 2019 @ 7pm Present: Cllr. Fisher (Meeting Chair) Cllr. Adams Cllr. Bunt Cllr. Carter Cllr. T. Libby Cllr. V. Libby Cllr. M. Shakerley Cllr. Talling In atten- Mrs Thompson (Parish Clerk) 18 Members of the public dance Minute AGENDA ITEMS Action Chairman’s Welcome and Public Forum – in the absence of Cllr. Moore, Cllr. Fisher took the Chair and opened the meeting. He welcomed those present and reminded attendees that as it was advertised as a public meeting it could be filmed or recorded by broadcasters, the media or members of the public. Cllr. Fisher explained to Mr Morley Tubb that the scheme for road safety improvements referred to under the Liskeard & Looe Network Panel Meeting item in the November Minutes referred to Lanteglos village. a. Minute 4b[i]/2019: PA18/03386/PREAPP, Land East of Bodinnick Heights, Old Road, Bodinnick – a number of emails/letters had been received from members of the public, who were opposed to this application and these had been circulated to Members and forward to CC Planning. Mr Gavin Shakerley spoke and raised points of concern in his transcript, namely: The Application – is for a proposed development restricted to the sale of plots of land for 7 open market houses and 7 affordable houses. Housing Need – local families want the provision of some affordable properties be made available for rent. Layout – the proposed plan outlines: Land area allocated to market housing is approximately @ 60%. Land allocated to amenity space 28%. -

Eye on Pelynt Issue No 2 of Your Own Community Newsletter August 2020

Eye on Pelynt Issue no 2 of your own community newsletter August 2020 Local author and photographer success story - page 11 Lockdown Stars Your personal harvest is here, allotments and gardens looking awesome. Time for a new lifestyle and a taste A pictorial jumble of tickling new diet to shed those kilos. Pages 12 - 13 people and community efforts - Page 10 Pelynt and local area news, what’s on, arts, farming, sport and local business Advertise here and help local people buy local services and goods. Prices start at only £9.75 for 1/6th page. All adverts in full colour, discount for a series. Keep your eye on Pelynt, it’s a growing community full of life. MINDBENDER Q1 Guess the next three Letters In the series: GtntL Aimed at youngsters, FENSA REG 37437 2 Welcome to ‘Eye on Pelynt’ and we hope that you enjoy the contents. It’s a new venture, financed by donations and advertising. The focus is on Pelynt people, activities and interests as well as looking at events in a much wider area. We hope to produce two more issues in 2020 and six in 2021. More on adverts and articles on page 17. The important ‘Parish Magazine’ is incorporated with a new look and carries information about local Church and Parish events and a section on our Methodist Church. In the current world of uncertainty the number of events is obviously down but we are all hoping that later in the year things will pick up with more confidence. Articles written by readers are essential for a successful newsletter and we would love to hear from you about any topic that may interest others. -

Mount & Warleggan Life

MOUNTMOUNT && WARLEGGANWARLEGGAN LIFELIFE JULY / AUGUST 2015 Number 89 Non-Parishioners 30p IT’S THAT TIME AGAIN SATURDAY 25TH JULY SO, polish up your onions Brush the soil off your potatoes Keep the carrot fly off your carrots Knit a pair of bootees AND gents, make a Victoria sandwich! Be there or you will miss out on a fun-filled day!! BIG DO STARTS AT MIDDAY In 2004 Michael Stuhrenberg, a German travel writer, stayed in Warleg- gan as a base to write in the magazine “GEO Special” on Cornwall. He was so enchanted by Warleggan that most of his article covered the vil- lage and it’s inhabitants. Below we commence the serialisation of a translation of the resultant article. BEST WISHES FROM WARLEGGAN Virginia Woolf, Daphne du Maurier, Rosamunde Pilcher are all very en- thusiastic about Cornwall`s wild beauty, particularly about its gorgeous coastline which also deeply impresses photographers. Geo-Special- writer Michael Stürenberg was keen on finding out what these celebrities might have failed to notice in Warleggan, a little hamlet on the moor. Michael Stührenberg from Warleggan/Cornwall to Gerda Stührenberg, Bremen-Aumund Dear Auntie Gerda, Since my phone call from our phone box on the moor (I am writing “our” because nobody else apart from us uses it), I have got the impression that there is a misunderstanding between us. Never did I mention that I dislike Cornwall`s coasts! You asked me, if the countryside was really comparable with the one portrayed in Rosamunde Pilcher`s novels like in “Cliffs of Love”. I just pointed out that we all disliked our trip to Land`s End, this famous sight of Cornwall has become a “theme park”, which is a negative development. -

Cornwall. Creed

DIRECTORY.] CORNWALL. CREED. 1077 register of baptisms dates from the year 1563; marriages, picturesque and interesting; it is the property of Francis 1679 ; burials, I559· The living is a vicarage, average Granville Gregor esq .lord of the manor and chief landowner. tithe rent-charge £I~ 10s., net yearly value £36, including The soil is shelf; subsoil, shelf. The chief crops are wheat, 10 acres of glebe, m the gift of the vicar of Probus, and held barley, oats and turnips. The area is 1,297 acres; rateable since 1868 by the Rev. Lewis Morgan Peter M.A. of Exeter value, £1,235; the population in 1891 was 84. College, Oxford, who is also rector of Ruan Lanihorne, and Sexton, John Corkhill. resides at Treviles. 'l'rewarthenick House, a plain stone Letters from Gramponnd Road via Tregony arrive at 9.30 building (now unoccupied), is a commodious mansion, on a.m. The nearest money order & telegraph office is at the western side of the river Fal, in grounds of about 50 Tregony acres in extent ; the various plantations and lawns and the This place is included in Tregony United School Board windings of the ri\·er combine to make the scenery highly district, formed Sept. 28, 1875 Alien Hy. gamekpr. to F. G. Gregor esq I Evans John, Gregor Arms P.H Pascoe William. gardener to F. G · Bennetto Thomas, farmer, Penpoll Hotten John, farmer Gregor esq. Trewarthenick Elliott John, farmer, Killiow, Penvose Pascoe Stephen, farmer, Grogarth SleemanThomas,farmer,Trewarthenick & Trelaska Y elland J ames, farmer, Mellingoose CRANTOCK (or ST. CRA~TOCK) is a parish and village on propriator, and held since 1878 by the Rev. -

Ref: LCAA1820

Ref: LCAA7916 Offers around £550,000 Owls House, Ladock, Nr. Truro, Cornwall, TR2 4PW FREEHOLD A grandly proportioned and extensive 5 bedroomed, 4 bathroomed south facing period house extending to almost 3,500sq.ft. – a significant portion of a grand country house within a few miles of Truro. An opportunity to live in one of the area’s most impressive historic residences enjoying the high ceilinged, detail filled accommodation with integral garage, carport and long south facing garden looking out across countryside. 2 Ref: LCAA7916 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: reception hall, dining room, drawing room, kitchen, sitting room, utility room, bathroom, integral garage, basement. First Floor: landing, master bedroom with balcony and en-suite shower room. 2 further bedrooms, shower room. Second Floor: landing, 2 double bedrooms (1 with former kitchenette off), bathroom. Outside: long south facing garden with large terrace, deck, summerhouse, shed and deep shrub lined boundaries. Broad carport to the front opening to the garage. DESCRIPTION Owls House is the central portion of one of the grandest houses in Cornwall and certainly within such close proximity to Truro. The non-listed building is believed to have been started in the late 1870’s by the Rector Stanford Raffles Flint (with family connection to Raffles Hotel, named after the founder of Singapore), who went on to become Archdeacon and a Canon of Truro Cathedral. As his family grew the house was increased in size significantly but always in keeping with the original to give a harmonious many gabled appearance over three storeys with outstanding chimneys and architectural details such as stone balustraded balconies and patterned stone detailing to the exterior.