Ladbrokes/Coral Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copy of Default Margin List

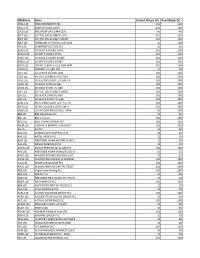

IRESSCode Name Current Margin (%) New Margin (%) 0HAL.LSE AEROVIRONMENT INC 100 100 0R22.LSE BARRICK GOLD CORP 100 100 17GK.LSE MEGAFON OAO-144A GDR 40 40 2LFT.LSE SG FTSE 100 X2 DAILY LONG 100 100 2SFT.LSE SG FTSE 100 X2 DAILY SHORT 100 100 38LF.LSE SBERBANK OF RUSSIA-GDR 144A 40 100 3IN.LSE 3I INFRASTRUCTURE PLC 20 20 3LAU.LSE SG GOLD X3 DAILY LONG 100 100 3LWO.LSE SG WTI X3 DAILY LONG 100 100 3SAU.LSE SG GOLD X3 DAILY SHORT 100 100 3SWO.LSE SG WTI X3 DAILY SHORT 100 100 42KU.LSE GRUPO CLARIN S-CL B GDR 144A 100 100 500U.LSE AMUNDI ETF S&P 500 20 20 51FL.LSE ELECTRICA SA-GDR-144A 100 100 53GI.LSE AFI DEVELOPMENT PLC-GDR 100 100 5DEL.LSE SG X5 LONG DAILY LEV DAX TR 100 100 5GOL.LSE SG GOLD LONG X5 GBP 100 100 5GOS.LSE SG GOLD SHORT X5 GBP 100 100 5SFT.LSE SG FTSE 100 X5 DAILY SHORT 100 100 5SIL.LSE SG SILVER LONG X5 GBP 100 100 5SIS.LSE SG SILVER SHORT X5 GBP 100 100 5UKL.LSE SG X5 LONG DAILY LEV FTSE TR 100 100 5WTI.LSE SG WTI X5 DAILY LONG GBP 2 100 100 66XD.LSE EDITA FOOD INDUSTRIES -144A 40 100 888.LSE 888 HOLDINGS PLC 20 30 88E.LSE 88 Energy Ltd 100 100 8PG.LSE EIGHT PEAKS GROUP PLC 100 100 98LM.LSE TURKIYE IS BANKASI-144A GDR 100 100 AA.LSE AA PLC 40 40 AA4.LSE AMEDEO AIR FOUR PLUS LTD 25 25 AAF.LSE AIRTEL AFRICA PLC 50 50 AAIF.LSE ABERDEEN ASIAN INCOME FUND L 25 30 AAL.LSE ANGLO AMERICAN PLC 15 10 AAOG.LSE ANGLO AFRICAN OIL & GAS PLC 100 100 AAS.LSE ABERDEEN ASIAN SMALLER COS-O 65 55 AASU.LSE AMUNDI ETF MSCI EM ASIA UCIT 20 25 AATG.LSE ALBION TECHNOLOGY & GENERAL 100 100 AAU.LSE ARIANA RESOURCES PLC 100 100 AAVC.LSE ALBION VENTURE -

Presentation Title

• • • • • Revenue by geography Revenue by business segment Revenue by product type 7% 3% 3% 4%4% 7% 47% 53% 34% 56% 82% Betting Gaming UK Australia US Italy and Spain Retail Online Other William Hill Australia William Hill US Note: Pie charts show 2016 full-year position • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • UK is the largest online market1 UK online market share2 Net revenue growth Online GGR (Eur m) 14% 6,000 550.7 527.4 5,000 11% 446.3 45% 406.7 4,000 321.3 10% 3,000 2,000 10% 1,000 7% 0 3% Paddy Power Betfair William Hill 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Bet365 Ladbrokes Coral SkyBet 888 Other 1. H2GC 2. Gambling Compliance Research Services, 2015 UK market share (October 2016). Pro forma combination of Paddy Power + Betfair share and Ladbrokes + Coral share • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • UK Sportsbook amounts wagered growth +10% • UK Gaming net revenue growth +8% • Registration conversion rate +17% (H2 v H1) Increase in value of new accounts (Q4 16 v Q4 • 15) +29% • 1. Seven weeks to 14 February 2017 • Largest business segment, representing 56% of revenue • Second largest operator with 2,375 LBOs1, equivalent to 27% market share2 • 46% betting (OTC) and 54% gaming (machine) • £893.9m net revenue and £162.0m adjusted operating profit in 2016 • Resilient, cash-generative business Delivering revenue growth against challenging economic backdrop UK Retail market share by shops3 Evolving product mix (gross win) 911.4 907.0 , 0 893.9 889.5 46% Other, 54% 13% William Hill, 3%4% 6% 27% 10% 4% Betfred, 12% 7% 19% 11% 837.9 25% 18% Ladbrokes Coral, 41% 2010 2016 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 1. -

28-June-18 AUSTRALIA 1.Margin 2.Can Go 3.Guaranteed Stock Ticker Rate Short?* Stop Premium

28-June-18 AUSTRALIA 1.Margin 2.Can go 3.Guaranteed Stock Ticker Rate short?* stop premium AGL Energy Limited AGL.AX / AGL AU 5% ✓ 0.3% ALS Limited ALQ.AX / ALQ AU 10% ✓ 1% AMA Group Limited AMA.AX / AMA AU 75% ☎ 1% AMP Limited AMP.AX / AMP AU 5% ✓ 0.3% APA Group APA.AX / APA AU 10% ✓ 0.3% APN Outdoor Group Limited APO.AX / APO AU 10% ✓ 1% APN Property Group Limited APD.AX / APD AU 25% ✘ 1% ARB Corporation Limited ARB.AX / ARB AU 20% ✓ 1% ASX Limited ASX.AX / ASX AU 10% ✓ 0.3% AVJennings Limited AVJ.AX / AVJ AU 25% ✘ 1% AWE Limited AWE.AX / AWE AU 25% ✘ 0.3% Abacus Property Group ABP.AX / ABP AU 20% ✓ 0.7% Accent Group Limited AX1.AX / AX1 AU 25% ✓ 1% Adelaide Brighton Limited ABC.AX / ABC AU 10% ✓ 0.3% Admedus Limited AHZ.AX / AHZ AU 25% ✘ 0.7% Ainsworth Game Technology Limited AGI.AX / AGI AU 25% ✓ 0.7% Alkane Resources Limited ALK.AX / ALK AU 25% ✘ 1% Altium Limited ALU.AX / ALU AU 15% ✓ 1% Altura Mining Limited AJM.AX / AJM AU 25% ☎ 1% Alumina Limited AWC.AX / AWC AU 10% ✓ 0.3% Amcil Limited AMH.AX / AMH AU 25% ✘ 1% Amcor Limited AMC.AX / AMC AU 5% ✓ 0.3% Ansell Limited ANN.AX / ANN AU 10% ✓ 0.3% Ardent Leisure Group AAD.AX / AAD AU 20% ✓ 1% Arena REIT ARF.AX / ARF AU 25% ☎ 1% Argosy Minerals Limited AGY.AX / AGY AU 25% ✘ 1% Aristocrat Leisure Limited ALL.AX / ALL AU 5% ✓ 0.3% Artemis Resources Limited ARV.AX / ARV AU 25% ✘ 1% Asaleo Care Limited AHY.AX / AHY AU 20% ✓ 0.7% Asian Masters Fund Limited AUF.AX / AUF AU 10% ✘ 0.3% Atlas Arteria Limited ALX.AX / ALX AU 10% ✓ 0.3% Aurelia Metals Limited AMI.AX / AMI AU 25% ☎ 1% Aurizon Holdings -

Building a Better Ladbrokes

Annual report and accounts 2015 BUILDING A BETTER LADBROKES Ladbrokes plc Annual report and accounts 2015 2015 highlights GROUP £1,174.6 £1,199.5 – Group net revenue up 2.1% (up 4.2% excluding £1,117.7 GROUP +5.1% +2.1% World Cup) NET REVENUE £M +3.1% – Operating profit(1) excluding High Rollers at £80.6m reflects investment in our new strategy announced in July and increased taxation +2.1% 2013 2014 2015 – Statutory operating loss of £15.4m reflects exceptional items of £99.0m mainly related to shop impairments and transaction costs – Strategy reset in July 2015, encouraging customer metrics in H2 – Ladbrokes announces proposed merger with the Coral Group to form Ladbrokes Coral plc RETAIL £800.9 £811.5 £827.4 – UK Retail net revenue up 2.0% (3.5% excluding RETAIL +1.3% +2.0% World Cup) NET REVENUE £M +8.3% – Self Service Betting Terminal roll out complete, encouraging staking growth delivered – Machines growth driven by lower-staking +2.0% 2013 2014 2015 B3 and slots DIGITAL (2) £242.8 – Sportsbook staking up 29% (3) TOTAL DIGITAL £215.1 +12.9% (2) +22.9% – Gaming net revenue up 13.3% NET REVENUE £M £175.0 -1.7% – Total actives up 15%(2) +12.9% 2013 2014 2015 AUSTRALIA £53.2 – Staking up 47%, net revenue up 54%, AUSTRALIA +53.8% actives up 65% NET REVENUE £M £34.6 (4) – Number 3 in brand awareness from +765% a standing start two years ago £4.0 +53.8% 2013 2014 2015 (1) Profit before tax, net finance expense and exceptional items. -

Credo Icav Interim Report and Unaudited Condensed

CREDO ICAV INTERIM REPORT AND UNAUDITED CONDENSED FINANCIAL STATEMENT S For the six months ended 30 June 2018 CREDO ICAV INTERIM REPORT AND UNAUDITED CONDENSED FINANCIAL STATEMENT S For the six months ended 30 June 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Information 3-6 Investment Manager’s Report 7-10 Condensed Statement of Financial Position 11-12 Condensed Statement of Comprehensive Income 13-14 Condensed Statement of Changes in Net Assets Attributable to Holders of Redeemable Participating Shares 15-16 Condensed Statement of Cash Flows 17-18 Notes to the Unaudited Condensed Financial Statements 19-27 Schedule of Investments of the Credo ICAV at 30 June 2018 28-37 Schedule of Portfolio Changes of the Credo ICAV at 30 June 2018 38-40 Supplementary Information 41 2 CREDO ICAV INTERIM REPORT AND UNAUDITED CONDENSED FINANCIAL STATEMENT S For the six months ended 30 June 2018 General Information Directors: Registered Office of the ICAV: Bryan Tiernan* 3rd Floor, IFSC House David Conway* International Financial Services Centre Ross Thomson (appointed 22 February 2018) Dublin 1 Kevin Lavery (resigned 22 February 2018) Ireland James Gardner (resigned 22 February 2018) All Directors are non-executive Management Company: Investment Manager and Distributor: FundRock Partners Limited** Credo Capital Plc Floor 3 8-12 York Gate 8/9 Lovat Lane 100 Marylebone Road London London, NW1 5DX EC3R 8DW United Kingdom Depository: Company Secretary: Société Générale S.A., Dublin Branch HMP Secretarial Limited 3rd Floor, IFSC House Riverside One IFSC Sir John Rogerson’s Quay Dublin 1 Dublin 2 Ireland Ireland Administrator: Irish Legal Advisers: Société Générale Securities Services McCann FitzGerald SGSS (Ireland) Limited Riverside One 3rd Floor, IFSC House Sir John Rogerson’s Quay IFSC Dublin 2 Dublin 1 Ireland Ireland Auditor: Deloitte Chartered Accountants & Statutory Audit Firm Deloitte & Touche House Earlsfort Terrace Dublin 2 * Independent Directors ** From 21 July 2018, the Management Company changed name from Fund Partners Limited to FundRock Partners Limited. -

Hydration of Greyhounds Changes to Trainers' Licensing and Residential

Vol 12 / No 4 28 February 2020 Fortnightly by Subscription calendar Trainers’ Notice: Hydration of Greyhounds Changes to Trainers’ Licensing and Residential Kennel Inspections SKILFUL SANDIE (t4) leads on the run up and at all eight bends to take the 2020 Ladbrokes Golden Jacket at Crayford for owners Graham Carpenter and Richard Photo: Steve Nash Marling, and trainer Patrick Janssens. FOR ALL THE LATEST NEWS - WWW.GBGB.ORG.UK Follow GBGB on Twitter @greyhoundboard @gbgbstaff and Instagram and Facebook CATEGORY ONE FINALS Date Distance Track Event Sun 1st March 480mH Central Park 2020 Cearnsport Springbok Fri 13th March 400m Romford Coral Golden Sprint Sat 21st March 500m Sheffield Racing Post Greyhound TV Steel City Cup Sat 21st March 480m Puppies Monmore Ladbrokes Puppy Derby 2020 Sat 4th April 695m Brighton & Hove Coral Regency Sat 16th May 500m Nottingham The Star Sports, ARC & LPS Greyhound Derby 2020 Further competitions to be confirmed. Above dates may be subject to change. STADIA CELEBRATE NHS STAFF AND VOLUNTEERS Greyhound stadia across the country will be offering special promotions to all NHS staff and volunteers throughout March to recognise the incredible work they do. This promotion is being run as a partnership between participating RCPA stadia and details of individual tracks’ offers will be appearing at tracks and online over the course of this week. David Evans, General Manager at Nottingham Greyhound Stadium, said: “We are delighted to be offering entrance, a racecard, a drink, burger and chips and a re-admission voucher here at Nottingham throughout March for NHS staff. It’s great that a number of tracks are coming together to run this promotion which is our opportunity to reward people locally who do so much to keep our communities thriving.” Karen McMillan, General Manager at Romford Greyhound Stadium, said: “We are really looking forward to NHS month here at Romford. -

Liste Des Valeurs Concernées Par Le BREXIT

ISIN Valeur Nature de ISIN Valeur Nature de regroupement regroupement GB00BMSKPJ95 AA ACTION QS0002902318 PORTFOLIO BPO SERVICES ACTION GB00B9GQVG73 AB DYNAMICS ACTION GB0006957293 PORTMEIRION GROUP LS-,05 ACTION GB00B3LXPB43 ABACO CAPITAL ACTION GB0006963689 PORVAIR ACTION GB0000037191 ABBEYCREST ACTION GB00BYWJZ743 POWER METAL RES. LS 0,001 ACTION GB00B6774699 ABCAM ACTION GB00B4WQVY43 POWERHOUSE ENER.GR.LS-005 ACTION GB0007352502 ABERDEEN DEVELOPMENT CAPITAL ACTION GB00B08JHZ23 POWERLEAGUE GROUP ACTION GB0000312933 ABERDEEN HIGH INCOME TRUST ACTION GB0006992480 PRELUDE TRUST ACTION GB0003920757 ABERDEEN JAPAN LS-,10 ACTION GB00BSZLMS59 PREM. VETERIN. GP. LS-,10 ACTION GB0000100767 ABERDEEN STAND.AS.F.LS-25 ACTION GB00B7N0K053 PREMIER FOODS ACTION GB0000059971 ABERDEEN. THAI INV.LS-,25 ACTION GB00BZB2KR63 PREMIER MI..GRP. LS-,0002 ACTION QS0002911012 ABINGWORTH BIOVENTURES VLP ACTION GB00B3DDP128 PRESIDENT ENERG.PLC LS-01 ACTION GB00BN65QN46 ABZENA ACTION GB00B1XFKR57 PRESSURE TECH.PLC LS -,05 ACTION GB00BYWF9Y76 ACACIA PHARMA GROUP ACTION GB0007015182 PRESTON NORTH END ACTION QS0002967642 ACCENT EQUITY ACTION QS0011204169 PRIMAYER ACTION QS0003014931 ACCES CAPITAL ACTION GB00B847MY01 PRIME MANTLA ACTION GB00BGQVB052 ACCESS INTELLIGEN. LS-,05 ACTION GB00B4ZG0R74 PRIME PEOPLE PLC LS-,10 ACTION GB0001771426 ACCESSO TECHNOLOGY ACTION GB00B40ZK133 PRIME UK HLDGS ACTION QS0003602388 ACCOMPLISH GP HOLDCO AO A ACTION GB00BKTCLJ25 PRIMORUS INV.PLC LS-,002 ACTION QS0003602396 ACCOMPLISH GP HOLDCO AO B ACTION GB00B0K32V35 PRINCIPLE CAPITAL INVEST.TRUST -

Interesting to Know April 2021

April 2021 Chaplains visit people in their place of work to offer friendship and to listen. Their support is unconditional, non-judgemental, independent and confidential. Interesting to Know.......... East Midlands Airport and the Gateway Industrial Cluster will have Freeport status. The bid to government said it has the potential to create 60,000 jobs. Freeport’s are a special kind of port where normal tax and customs rules do not apply. This year 90.1% of Nottinghamshire children have been offered their parents’ first preference secondary school for this September (2021). That is 8,349 students out of a total of 9,266 that applied on time for a school place. Nottingham Trent University has revealed plans for a new 57,000 sq ft Art & Design building on the corner of Shakespeare Street and North Sherwood Street in the city centre. The university says the new development will place Nottingham as the centre for film, television, animation, UX design, games design and graphic design. Domestic & General, which is currently based in Talbot Street, is to move its hub to Station Street, bringing £50 million of direct investment to the city. The new building will host up to 1,000 employees. Guess what - the company’s current office is to be turned into student flats. Bingham is to get a £16 million leisure centre and the Moorbridge Industrial Estate in Bingham is to have 23 brand new commercial units that will provide considerable employment space locally. Almost a quarter of UK households have no savings at all. Construction has started on the 348-apartment PRS development on Queens Road in Nottingham. -

Leading the Future of Online Gaming 2016

LEADING THE FUTURE OF ONLINE GAMING 888 HOLDINGS PLC ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2016 WELCOME TO 888: THE NAME CUSTOMERS CAN TRUST 888 is one of the world’s most popular online gaming entertainment and solutions providers. 888’s mission is to supply customers with market-leading online gaming entertainment, above all in a safe and secure environment. At the heart of 888’s business is its cutting- edge proprietary gaming technology and associated platforms which are operated by highly sophisticated business analytics- driven marketing and customer relationship management. These strengths enable 888 to deliver to customers and Business to Business partners alike market-leading and continually innovative online gaming entertainment products and solutions. 888 is always mindful of the complex regulatory environment in which it operates and the social responsibility that comes hand-in-hand with the online gaming industry. 888 continually invests time and resources in caring for and protecting its customers and, by successfully doing this, 888’s business will continue to grow and prosper. OVERVIEW OF 888 Overarching 888 brand 888’s B2C offering 888’s B2B offering This Annual Report may contain statements which are not based on current or historical fact and which are forward looking in nature. These forward looking statements reflect knowledge and information available at the date of preparation of this Annual Report and 888 Holdings plc (the “Company”) and its subsidiaries (together, “888”, or the “Group”) undertake no obligation to update these forward looking statements. Such forward looking statements are subject to known and unknown risks and uncertainties facing 888 including, without limitation, those risks described in this Annual Report and other unknown future events and circumstances which can cause results and developments to differ materially from those anticipated. -

Oxford Stadium – Stage 1 Commercial Viability Assessment

26th March 2018 Oxford Stadium – Stage 1 Commercial Viability Assessment 1 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 Purpose of this report ................................................................................................................. 3 Work undertaken ........................................................................................................................ 4 Limitations................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2: Evaluation of the Oxford Stadium site ......................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 The size and location of the site ................................................................................................. 6 A brief history of the site and current activities ......................................................................... 9 Oxford Stadium’s catchment area ............................................................................................ 11 Economy .............................................................................................................................................................. 11 Visitor economy .................................................................................................................................................. -

GPWA Times Magazine

Ad CWC And once again, we’ve selected some very Letter from the director interesting people to profile. This time around, our main focus is on some of our I’m pleased and excited to present the most dedicated GPWA members (seven), second edition of GPWA Times magazine. with a few affiliate managers (three) In the relatively brief passage of time included for good measure. between this issue and the last, people in our industry have been redoubling their efforts We hope you enjoy reading the GPWA to broaden their reach and gain access both Times magazine. We think you’ll find plenty to established and emerging markets. All of facts, figures and advice that you’ll be that activity is reflected in the contents of able to use to improve every facet of your this issue. operation. Our cover story on Malta takes a close Finally, we invite you to stop by GPWA.org look at why online gaming sites are lining to familiarize yourself with our fantastic up to be licensed there. One reason is that community and sign up for the weekly Malta-registered sites can advertise on electronic edition of GPWA Times. British TV – which is the subject of another story. Antigua is hoping its sites will also be Sincerely, OK’d for U.K. advertising very soon; in the meantime, they’ve retained a tough Texas lawyer to argue their WTO case against the U.S. Casino City has done some extensive research on changes in the online gaming Michael A. Corfman market, which I’ve written about. -

FAIR PLAY Performance Update Corporate Responsibility Report 2016 Corporate Responsibility Report 2016 Fair Play: a Shared Goal

FAIR PLAY Performance update Corporate Responsibility Report 2016 Corporate Responsibility Report 2016 Fair Play: a shared goal Our aim is to grow a socially responsible and sustainable betting and gaming business, creating value for all our stakeholders, helping our people make the most of their potential and providing a safe, enjoyable and exciting leisure experience for our customers. Three strategic aims of our Corporate Responsibility programme: Leading the way in Making a positive impact Operating safely and Responsible betting and gaming on our communities with integrity Contents At Ladbrokes Coral, we serve millions of retail customers every year and now have more than one million multi-channel 01 Fair Play: a shared goal customers across all our platforms. We can trace our roots back 02 Highlights and achievements to 1886 and know that to stay in business for the next 100 03 Business overview years, we must continue to listen to our stakeholders, conduct 04 Chief Executive’s introduction our business in a responsible manner and promote higher standards for the sector as a whole. That is what we refer 06 Our vision for responsible business to as Fair Play. practice at Ladbrokes Coral 07 Our CR Governance structure The merger between Ladbrokes and Coral on 1 November 2016 created a new Ladbrokes Coral family, with more than 26,000 08 Engaging with our stakeholders colleagues operating across 15 countries, including the UK, 10 Establishing our priorities Australia, Ireland, Belgium, Gibraltar, Italy and Spain. 11 2016 Performance highlights This document describes our Corporate Responsibility (CR) 14 Our CR strategy performance over the past year for our global business.