City of Wenatchee 2013‐2017 Housing & Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C

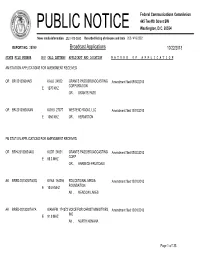

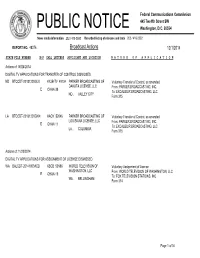

REPORT NO. PN-1-210205-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/05/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000132840 Assignment AM WING 25039 Main 1410.0 DAYTON, OH ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132974 Assignment FM KKUU 11658 Main 92.7 INDIO, CA ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132926 Assignment AM WSGW 22674 Main 790.0 SAGINAW, MI ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132914 Assignment FM WDLD 23469 Main 96.7 HALFWAY, MD ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132842 Assignment AM WJQS 50409 Main 1400.0 JACKSON, MS ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession Page 1 of 66 REPORT NO. PN-1-210205-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/05/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

And Lots of Dx!

The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association SEPTEMBER 2007 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers PACK UP THE CAR WITH ANTENNAS AND RADIOS, KISS THE WIFE AND KIDS GOOD-BYE, LOAD UP THE CAR WITH YOUR BUDDIES AND DRIVE 900 MILES TO A CABIN IN A PLACE SO REMOTE IT’S A 100 MI ROUND TRIP TO THE DAIRY QUEEN AND BACK. PEACE, QUIET AND DX!! Keosauqua, Iowa, July 2007 17 CONVENTION 2007 IS HISTORY! MONTHS MAJOR TROPO HITS THE MIDWEST REMAINING UNTIL ANALOG TV SHUTOFF AM AND FM IBOC GET THE OFFICIAL TH START ON SEPTEMBER 14 . AND LOTS OF DX! TV and FM DXing was never so much fun! THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Dave Williams, Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Chris Kadlec, Peter Baskind and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info SEPTEMBER 2007 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 TV News…Doug Smith 4 Finally! For those of you online with an email FM News 12 address, we now offer a quick, convenient and Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 20 secure way to join or renew your membership Southern FM DX…John Zondlo 42 in the WTFDA from our page at: Western TV DX…Dave Williams 46 http://fmdx.usclargo.com/join.html Eastern TV DX…Nick Langan 51 Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 55 Dues are $25 if paid to our Paypal account. -

Microsoft Outlook

Emails pertaining to Gateway Pacific Project For April 2013 From: Jane (ORA) Dewell <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, April 01, 2013 8:12 AM To: '[email protected]'; Skip Kalb ([email protected]); John Robinson([email protected]); Brian W (DFW) Williams; Cyrilla (DNR) Cook; Dennis (DNR) Clark; Alice (ECY) Kelly; Loree' (ECY) Randall; Krista Rave-Perkins (Rave- [email protected]); Jeremy Freimund; Joel Moribe; 'George Swanaset Jr'; Oliver Grah; Dan Mahar; [email protected]; Scott Boettcher; Al Jeroue ([email protected]); AriSteinberg; Tyler Schroeder Cc: Kelly (AGR) McLain; Cliff Strong; Tiffany Quarles([email protected]); David Seep ([email protected]); Michael G (Env Dept) Stanfill; Bob Watters ([email protected]); [email protected]; Jeff Hegedus; Sam (Jeanne) Ryan; Wayne Fitch; Sally (COM) Harris; Gretchen (DAHP) Kaehler; Rob (DAHP) Whitlam; Allen E (DFW) Pleus; Bob (DFW) Everitt; Jeffrey W (DFW) Kamps; Mark (DFW) OToole; CINDE(DNR) DONOGHUE; Ginger (DNR) Shoemaker; KRISTIN (DNR) SWENDDAL; TERRY (DNR) CARTEN; Peggy (DOH) Johnson; Bob (ECY) Fritzen; Brenden (ECY) McFarland; Christina (ECY) Maginnis; Chad (ECY) Yunge; Douglas R. (ECY) Allen; Gail (ECY) Sandlin; Josh (ECY) Baldi; Kasey (ECY) Cykler; Kurt (ECY) Baumgarten; Norm (ECY) Davis; Steve (ECY) Hood; Susan (ECY) Meyer; Karen (GOV) Pemerl; Scott (GOV) Hitchcock; Cindy Zehnder([email protected]); Hallee Sanders; [email protected]; Sue S. PaDelford; Mary Bhuthimethee; Mark Buford ([email protected]); Greg Hueckel([email protected]); Mark Knudsen ([email protected]); Skip Sahlin; Francis X. Eugenio([email protected]); Joseph W NWS Brock; Matthew J NWS Bennett; Kathy (UTC) Hunter; ([email protected]); Ahmer Nizam; Chris Regan Subject: GPT MAP Team website This website will be unavailable today as maintenance is completed. -

Benton City Blaine Bremerton Brewster

KUJ-F CHR KCED Hot AC* Benton City 99.1 52000w 1263ft DA 91.3 1000w -72ft +New Northwest Broadcasters, LLC Centralia Community College KMMG Regional Mexican [Repeats: KDYK 1020] Sister to: KALE, KEGX, KIOK, KKSR, KTCR 360-736-9391 96.7 820w 889ft 509-783-0783 fax: 509-735-8627 600 Centralia College Blvd, 98531 +Bustos Media Corporation 830 N Columbia Center Blvd Ste B2 GM Wade Fisher Sister to: KDYK, KDYM, KZML, KZTA, KZTB Kennewick 99336 Centralia/Chehalis Market 509-457-1000 fax: 509-452-0541 GM Kurt Luchs SM Ken Olsen PO Box 2888, Yakima 98907 PD A.J. Brewster CE Mike Powers KNBQ Country 706 Butterfield Rd, Yakima 98901 www.power991fm.com 102.9 70000w 2192ft GM Ricky Tatum SM Ruben Muniz Richland/Kennewick/Pasco Arbitron 7.2 Shr 1700AQH -Clear Channel Communications PD Jesus Rosales CE Dewey Trostell 2nd market Walla Walla 206494-2000 fax: 206-286-2376 www.radlolagrande.com/yakima/ 351 Elliott Ave W Ste 300, Seattle 98119 Richland/KennewickPasco Arbitron 3.0 Shr 700 AQH GM Michele Grosenick SM Alison Hesse Burien PD Jay Kelly CE Ken Broeffle Blaine www.qcountry1029.com KGNW Religious Teaching Centralia/Chehalis Market 820 50000/5000 DA-2 KARI Religious Teaching 2nd market Seattle/Tacoma/Everett +Salem Communications Corp. 550 5000/2500 DA-2 3rd market Olympia Sister to: KKMO, KKOL, KLFE, KNTS -^Multicultural Radio Broadcasting 206443-8200 fax:206-777-1133 Sister to: KVRI 2201 6th Ave Ste 1500, Seattle 98121 Centralia-Chehalis 360-371-5500 fax:360-371-7617 GM Andrew Adams SM Chad Gammage Box 75150, White Rock BC V4B 5 PD Dave Drui CE Monte Passmore KITI Oldies 4840 Lincoln Rd, Blaine 98230 www.kgnw.com 1420 500015000 DA-2 GM/SM/PD Gary Nawman CE Mike Gilbert Seattle/Tacoma/EvereH Arbitron 0.3 Shr 38,100 Cume +Premier Broadcasters, Inc. -

E-Skip Winds Down Tropo Picks

The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX SEPTEMBER 2003 The Magazine For TV and FM Dxers GREG BARKER’S INDIANA ANTENNA SYSTEM! E-SKIP WINDS DOWN TROPO PICKS UP! COMPLETE COVERAGE OF FALL TROPO FALL E-SKIP MS,AU DTV AND IBOC AND EVERYTHING IN THE WORLD OF TV AND FM DXING TV AND FM DXING WAS NEVER SO MUCH FUN1 THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: TOM BRYANT, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, DAVE JANOWIAK AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Dave Janowiak Webmaster: Tim McVey Editorial Staff: Steven Wiseblood, Victor Frank, George W. Jensen, Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Matt Sittel, Doug Smith, Thomas J. Yingling, Jr. and John Zondlo, Our website: www.anarc.org/wtfda ANARC Rep: Jim Thomas, Back Issues: Dave Nieman ELECTRONIC EDITION for SEPTEMBER 2003 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email TV News…Doug Smith 4 address, we now offer a quick, convenient Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 10 and secure way to join or renew your Eastern TV DX…Matt Sittel 12 membership in the WTFDA from our page at: Southern FM DX…John Zondlo 17 http://fmdx.usclargo.com/join.html Western TV DX…Victor Frank 23 Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 37 Dues are $25 if paid from our Paypal account. -

The Oxford Democrat: Vol. 51, No. 8

A Oo )D IN\ K»TUKJ4T Hm dmI dollar la the worUI la THR HOME MAKKTS COMHN that «Mt !i u mi«*I by mm* good. boaeat t uipioyuaeat of tbe lirart or bau<l Wraith WAH MB* OAT'ft HINT. A*t> H*>« IT that < ■ by rbaara la ao turaaar* of the TASKS capacity of m p-ieaeaaor, ami la aeeer ap- j>r« i*l< J III t!ut wbkb la earned Many ■v uh ut v uton people are traveling atralgbt lu the puur Ihdim by reaaon of tbelr on.lue ragrru. aa to «•» la ibe illwriina They waat 11. abal >• tto oppoelte War Mr* Matt Hcmotral ana My rirbra at a boan-1. Thry have otbrra Ml tor? UlktMTMirMlnll^ <5te III UtrIf (ttnii by toate lucky apaculatlva u*ao-t raa Jo Uta Wt vote* aa a aalf hbarty %t* »p|»r*r».1 ©xfari ra, antl rua< iu<l« lh»y rooa. NTMBEH N •»!«• Hita< Accordingly la gom thnr ill- at 11m toor of Ito <HH. Maortortr FEBRUARY 215. IHS4. YOU MK LI PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, I- wh.< b. Un to oae, aavar — Ml la Um »•»■ U»ey • kM> i Unit «<'Mi crytai tfaiB. if fall ;i|M. for tba l»taoarat SKATING NOTK0. I petroleum baa awalioirwl ap '• awl Marabout were ar- HOU.l.K a tho«eaa<la of rkiktrra ir» all wall to!r*p m la*. aad A SI W WORLD I.KOKNP Tom Mrrnim wu ailent tbat ! Hermiooe tad tba form* of taveatore— Tto tad Ml IM Joki yoa ad* alraly unuaually top A WOR|» To iOTfl. -

2020 Delegate Selection Plan

Delegate Selection Plan For the 2020 Democratic National Convention Issued by the Washington State Democratic Party (The State Democratic Chair shall be empowered to make any technical revisions to this document as required by the DNC Rules and Bylaws Committee to correct any omissions and/or deficiencies as found by the DNC Rules and Bylaws Committee to ensure its full compliance with Party Rules. (Reg. 2.5, Reg. 2.6 & Reg. 2.7)) 1 The Washington State Delegate Selection Plan For the 2020 Democratic National Convention Table of Contents SECTION I INTRODUCTION & DESCRIPTION OF DELEGATE SELECTION PROCESS ....................................3 SECTION II PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES ...............................................................................................8 SECTION III SELECTION OF DELEGATES AND ALTERNATES ....................................................................9 SECTION IV NATIONAL CONVENTION STANDING COMMITTEE MEMBERS .......................................... 33 SECTION V THE DELEGATION ............................................................................................................ 37 SECTION VI PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORS ................................................................................................ 38 SECTION VII GENERAL PROVISIONS AND PROCEDURAL GUARANTEES ................................................ 41 SECTION VIII AFFIRMATIVE ACTION, OUTREACH AND INCLUSION PLAN ............................................. 45 SECTION IX CHALLENGES ................................................................................................................. -

Broadcast Applications 10/22/2013

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28099 Broadcast Applications 10/22/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED OR BR-20130924AIS KAJO 24822 GRANTS PASS BROADCASTING Amendment filed 09/30/2013 CORPORATION E 1270 KHZ OR , GRANTS PASS OR BR-20130930AXM KOHU 27077 WESTEND RADIO, LLC Amendment filed 10/01/2013 E 1360 KHZ OR , HERMISTON FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED OR BRH-20130924AIO KLDR 24821 GRANTS PASS BROADCASTING Amendment filed 09/30/2013 CORP. E 98.3 MHZ OR , HARBECK-FRUITDALE AK BRED-20130927AGQ KYKA 164296 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA Amendment filed 10/01/2013 FOUNDATION E 104.9 MHZ AK , MEADOW LAKES AK BRED-20130927AYA KIAM-FM 174373 VOICE FOR CHRIST MINISTRIES, Amendment filed 10/01/2013 INC E 91.9 MHZ AK , NORTH NENANA Page 1 of 133 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28099 Broadcast Applications 10/22/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED TX BRFT-20130411ACU K210DF 122072 ALELUYA BROADCASTING Amendment filed 10/17/2013 NETWORK E 89.9 MHZ TX , LAKE JACKSON OR BRFT-20130924AIP K251AX 24825 GRANTS PASS BROADCASTING Amendment filed 09/30/2013 CORPORATION E 98.1 MHZ OR , MEDFORD OR BRFT-20130924AIQ K283AE 24826 GRANTS PASS BROADCASTING Amendment filed 09/30/2013 CORPORATION E 104.5 MHZ OR , CAVE JUNCTION OR BRFT-20130924AIR K259AE 24827 GRANTS PASS BROADCASTING Amendment filed 09/30/2013 CORPORATION E 99.7 MHZ OR , WOLF CREEK OR BRFT-20130926APB K290BK 138665 CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN Amendment filed 09/30/2013 FALLS, INC. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 The

Case 2:05-cv-00927-JCC Document 300-2 Filed 01/07/11 Page 1 of 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Honorable John C. Coughenour 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON AT SEATTLE 10 WASHINGTON STATE REPUBLICAN NO. CV05-0927 JCC 11 PARTY, et al., APPENDIX B – AUTHENTICITY 12 Plaintiffs, STIPULATED, ADMISSIBILITY DISPUTED 13 WASHINGTON STATE DEMOCRATIC CENTRAL 14 COMMITTEE, et al., 15 Plaintiff Intervenors, 16 and 17 LIBERTARIAN PARTY OF WASHINGTON STATE, et al., 18 Plaintiff Intervenors, 19 v. 20 STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al., 21 Defendant Intervenors, 22 WASHINGTON STATE GRANGE, 23 Defendant Intervenor. 24 25 26 APPENDIX B – AUTHENTICITY 1 ATTORNEY GENERAL OF WASHINGTON Complex Litigation Section STIPULATED, ADMISSIBILITY 800 Fifth Avenue, Suite 2000 DISPUTED--No. CV05-0927 JCC Seattle, WA 98104-3188 (206) 464-7352 Case 2:05-cv-00927-JCC Document 300-2 Filed 01/07/11 Page 2 of 31 APPENDIX B Authenticity Stipulated, Admissibility Disputed PLAINTIFFS: Pltf Deft Description of Exhibit Stip to Offered Admitted No. No. Authen 1 News article: “Primary Ballot Count Leaning Toward Y* Republican Candidates.” 4 News article: “Counties still tabulating ballots from Y* primary.” 5 News article: “Top Two Outcome Gives Second Chance.” Y* 6 News article: “Top Two Primary Format Delivers Surprise.” Y* 7 News article: “Voters the Real Winners in Top Two Y* Primary.” 8 News article: “Attack of the Winnows, and Other Y* Wordsmithing Fun.” 9 News article: “In Our View: Top Two Primary Is a Huge Y* Success.” 10 News article: “Political Beat: Dunn Finally -

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

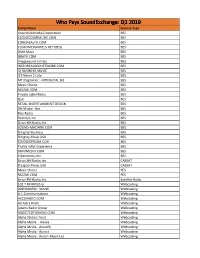

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Broadcast Actions 12/1/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48376 Broadcast Actions 12/1/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 06/24/2014 DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR TRANSFER OF CONTROL DISMISSED ND BTCCDT-20131220GLX KXJB-TV 49134 PARKER BROADCASTING OF Voluntary Transfer of Control, as amended DAKOTA LICENSE, LLC From: PARKER BROADCASTING, INC. E CHAN-38 To: EXCALIBUR BROADCASTING, LLC ND , VALLEY CITY Form 315 LA BTCCDT-20131220GNN KAQY 52046 PARKER BROADCASTING OF Voluntary Transfer of Control, as amended LOUISIANA LICENSE, LLC From: PARKER BROADCASTING, INC. E CHAN-11 To: EXCALIBUR BROADCASTING, LLC LA ,COLUMBIA Form 315 Actions of: 11/20/2014 DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE DISMISSED WA BALCDT-20141003ACD KBCB 53586 WORLD TELEVISION OF Voluntary Assignment of License WASHINGTON, LLC. From: WORLD TELEVISION OF WASHINGTON, LLC E CHAN-19 To: FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC. WA , BELLINGHAM Form 314 Page 1 of 34 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48376 Broadcast Actions 12/1/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 11/21/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED WA BAL-20140917AAY KMIA 33683 ADELANTE MEDIA OF SEATTLE Voluntary Assignment of License LICENSE LLC From: ADELANTE MEDIA OF SEATTLE LICENSE, LLC E 1210 KHZ To: BUSTOS MEDIA HOLDINGS, LLC WA , AUBURN-FEDERAL WAY Form 314 Rescinded 11/20/14.