Internet Addiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prevalence and Predictors of Video Game Addiction: a Study Based on a National Representative Sample of Gamers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Nottingham Trent Institutional Repository (IRep) Int J Ment Health Addiction DOI 10.1007/s11469-015-9592-8 Prevalence and Predictors of Video Game Addiction: A Study Based on a National Representative Sample of Gamers Charlotte Thoresen Wittek1 & Turi Reiten Finserås1 & Ståle Pallesen2 & Rune Aune Mentzoni2 & Daniel Hanss3 & Mark D. Griffiths4 & Helge Molde1 # The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Video gaming has become a popular leisure activity in many parts of the world, and an increasing number of empirical studies examine the small minority that appears to develop problems as a result of excessive gaming. This study investigated prevalence rates and predictors of video game addiction in a sample of gamers, randomly selected from the National Population Registry of Norway (N=3389). Results showed there were 1.4 % addicted gamers, 7.3 % problem gamers, 3.9 % engaged gamers, and 87.4 % normal gamers. Gender (being male) and age group (being young) were positively associated with addicted-, problem-, and engaged gamers. Place of birth (Africa, Asia, South- and Middle America) were positively associated with addicted- and problem gamers. Video game addiction was negatively associ- ated with conscientiousness and positively associated with neuroticism. Poor psychosomatic health was positively associated with problem- and engaged gaming. These factors provide insight into the field of video game addiction, and may help to provide guidance as to how individuals that are at risk of becoming addicted gamers can be identified. Keywords Video game addiction . -

Computer Addiction in Adolescents and Young Adults, Solutions for Moderating and Motivating for Success

Computer Addiction in Adolescents and Young Adults, Solutions for Moderating and Motivating for Success Kenneth Woog, Psy. D. Clinical Psychologist, CEO Woog Laboratories, Inc. [email protected] (949) 422-4120 The Dangerous World of Personal Computers •Media attention to MySpace and Pedophiles •News reports of abductions, murders linked to MySpace •Stepped up Law Enforcement Entrapment •“To Catch a Predator…n” Dateline NBC - Perverted-Justice.com •Larger, more widespread, but less discussed problem: Excessive Computer Use and Addiction •Lowered Academic Performance •Game play - Social Isolation, Depression •Online socialization: exposure to deviant peers •Health problems •Repetitive Stress Injury, obesity, vision problems, sleep •Family Conflict (c)2007 Kenneth M. Woog, Psy. D. 2 2002: My Introduction to Computer Addiction •Two 15 y/o males referred by sheriff’s department •One attempted to strangle mother with power cord when she unplugged the computer to get him off •One stabbed brother with kitchen knife when he would not get up from computer to let him play •No history of mental illness or behavior problems •Teens denied addiction and were resistant to counseling •Both placed on involuntary psychiatric holds. •Cycles of abstinence, behavior contracting did not help cure the addiction or motivation positive change •Attempts to help parents reestablish parental authority failed •Limited success with these clients led me to search for effective treatment methods. Mostly non-specific methods were identified •Conducted research and nationwide survey of mental health professionals in 2003/2004 (c)2007 Kenneth M. Woog, Psy. D. 3 Computer Addiction Research / Press •Very little research, some sensationalized press •Controversial since 1989 - does it really exist? •Symptom of other disorders or distinct disorder? •Blame? - Game Developers vs. -

Exploring Pattern of Smartphone Addiction Among Students In

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-4, Issue-5, Sep – Oct 2019 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.45.37 ISSN: 2456-7620 Exploring Pattern of Smartphone Addiction among Students in Secondary Schools in Lagos State and its Counselling EJIE, Benedette Onyeka1; EJIE, Oscar Chisom2; EJIE, Cynthia Nchedochukwu3; EJIE, Ann Uchechukwu4; EJIE, Brian Ikechukwu5 1Department of Educational Foundations and Counselling Psychology, Faculty of Education, Lagos State University, Ojo, Lagos, Nigeria 2Department of Environmental Management, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, P.M.B. 02, Uli, Anambra State, Nigeria 3Department of Guidance and Counselling, Faculty of Education, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria, 4Department of Cultural and Creative Arts and English Language, Adeniran Ogunsanya College of Education, Otto-Awori, Lagos, Nigeria. 5Department of Science and Technology Education, Lagos State University, Ojo- Lagos Email: [email protected],2 [email protected],3 [email protected], [email protected], 5 [email protected] Abstract— Smartphone addiction could be described as smartphone over-dependence or smartphone overuse. It is a form of addiction that has become one of the most prevalent non-drug addictions today. Smartphone overuse was nevertheless shown to imply various types of dysfunctional behaviours and adverse consequences.This paper therefore, eexplored pattern of smartphone addiction among students in secondary schools in Lagos state and its counselling. One research question and onehypothesis were raised to guide the research. The sample consisted of one hundred and fifty (150) students randomly selected from students in secondary schools in Lagos state. A 30- item questionnaire titled “Pattern of Smartphone Addiction” (PSA) was designed for data collection. -

Self-Help: Computer Addiction

Resources and Support for Families with students facing Internet Addictions Self-Help: Computer Addiction Some people develop bad habits in their computer use that cause them significant problems in their lives. The types of behavior and negative consequences are similar to those of known addictive disorders; therefore, the term Computer or Internet Addiction has come into use. While anyone who uses a computer could be vulnerable, those people who are lonely, shy, easily bored, or suffering from another addiction or impulse control disorder as especially vulnerable to computer abuse. Computer abuse can result from people using it repeatedly as their main stress reliever, instead of having a variety of ways to cope with negative events and feelings. Other misuses can include procrastination from undesirable responsibilities, distraction from being upset, and attempts to meet needs for companionship and belonging. While discussions are ongoing about whether excessive use of the computer/Internet is an addiction, the potential problematic behaviors and effects on the users seem to be clear. The Signs of Problematic Computer Use A person who is “addicted” to the computer is likely to have several of the experiences and feelings on the list below: How many of them describe you? You have mixed feelings of well-being and guilt while at the computer. You make unsuccessful efforts to quit or limit your computer use. You lose track of time while on the computer. You neglect friends, family and/or responsibilities in order to be online. You find yourself lying to your boss and family about the amount of time spent on the computer and what you do while on it. -

The Effects of Adolescents' Relationships with Parents And

Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research - ISSN 2288-6168 (Online) 106 Vol. 9 No.2 May 2021: 106-141 http://dx.doi.org/10.15206/ajpor.2021.9.2.106 The Effects of Adolescents’ Relationships with Parents and School/Institute Teachers as Protective Factors on Smartphone Addiction: Comparative Analysis of Elementary, Middle, and High School Levels in South Korea1 Indeok Song2 Joongbu University, South Korea Abstract This study was conducted for the purpose of empirically analyzing the effects of adolescents’ relationships with major adults as protective factors for smartphone addiction. Specifically, the study compared the discriminatory effects of adolescents’ relationships with their parents, school teachers, and educational institute teachers on smartphone addiction among elementary, middle, and high school students in Korea. Analyzing the data of the 2019 Korean Children & Youth Happiness Index (N=7,454), it was found that relationships with adults were significant factors in explaining the level of smartphone addiction even after controlling for the influences of adolescents’ demographics, usage time, and friendship factors. For elementary school students, good relationships with their mothers and school teachers decreased the risk of smartphone addiction. On the other hand, in the case of middle school students, only a good relationship with father functioned as a protective factor. Good relationships with their fathers and institute teachers decreased the level of high school students’ smartphone addiction. Based on these findings, this study discussed on the development of programs and policies for prevention and intervention of adolescents’ smartphone addiction and provided suggestions for follow-up research in the future. Keywords: smartphone addiction, adolescent, protective factors, relationships with adults, South Korea 1 This paper was supported by Joongbu University Research & Development Fund in 2020. -

Internet Addiction and Psychopathology in Turkey

TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology – January 2011, volume 10 Issue 1 INTERNET ADDICTION AND PSYCHOPATOLOGY Mustafa KOÇ ABSTRACT This study examined the relationships between university students’ internet addiction and psychopathology in Turkey. The study was based on data drawn from a national survey of university students in Turkey. 174 university students completed the SCL-90-R scale and Addicted Internet Users Inventory. Results show that students who use internet six hours and more a day have psychiatric symptoms. Students whose addicted internet usage have psychiatric symptoms such as Somatization, Obsessive Compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism more than students whose nonaddictet internet usage. Keywords: Internet addiction; symptoms; psychopathology, university students INTRODUCTION Technology is changing the nature of problems (Young, 1996). Symptoms often identified were a preoccupation with the internet, an inability to control use, hiding or lying about the behaviour, psychological withdrawal, and continued use despite consequences of the behaviour (Young, 2007). The internet has positive aspects including informative, convenient, resourceful and fun, but for the excessive internet users, these benefits turn out to be useless. Most individuals use the internet without negative consequences and even benefit from it, but some individuals do suffer from negative impacts. Psychologists and educators are aware of the potential negative impact from excessive use and related physical and psychological problems (Griffiths & Greenfield, 2000). Users who spend a significant amount of time online often experience academic, relationship, financial, and occupational difficulties, as well as physical impairments (Chou, 2001). Some researchers (Brenner, 1997; Nie & Erbring, 2000) have even linked internet use with an increase in psychological difficulties such as depression and loneliness. -

Proposed Gaming Addiction Behavioral Treatment Method*

ADDICTA: THE TURKISH JOURNAL ON ADDICTIONS Received: May 20, 2016 Copyright © 2016 Turkish Green Crescent Society Revision received: July 15, 2016 ISSN 2148-7286 eISSN 2149-1305 Accepted: August 29, 2016 http://addicta.com.tr/en/ OnlineFirst: November 15, 2016 DOI 10.15805/addicta.2016.3.0108 Autumn 2016 3(2) 271–279 Original Article Proposed Gaming Addiction Behavioral Treatment Method* Kenneth Woog1 Computer Addiction Treatment Program of Southern California Abstract This paper proposes a novel behavioral treatment approach using a harm-reduction, moderated play strategy to treat computer/video gaming addiction. This method involves the gradual reduction in game playtime as a treatment intervention. Activities that complement gaming should be reduced or eliminated and time spent on reinforcing activities competing with gaming time should be increased. In addition to the behavioral interventions, it has been suggested that individual, family, and parent counseling can be helpful in supporting these behavioral methods and treating co-morbid mental illness and relational issues. The proposed treatment method has not been evaluated and future research will be needed to determine if this method is effective in treating computer/video game addiction. Keywords Internet addiction • Internet Gaming Disorder • Video game addiction • Computer gaming addiction • MMORPG * This paper was presented at the 3rd International Congress of Technology Addiction, Istanbul, May 3–4, 2016. 1 Correspondence to: Kenneth Woog (PsyD), Computer Addiction Treatment Program of Southern California, 22365 El Toro Rd. # 271, Lake Forest, California 92630 US. Email: [email protected] Citation: Woog, K. (2016). Proposed gaming addiction behavioral treatment method. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 3, 271–279. -

Internet Addiction and the Relationship to Self and Interpersonal

INTERNET ADDICTION AND THE RELATIONSHIP TO SELF AND INTERPERSONAL FUNCTIONING WITHIN THE ALTERNATIVE MODEL FOR PERSONALITY DISORDERS (AMPD): IMPLICATIONS FOR PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Antioch University Seattle In partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY by Lori Woehler ORCID Scholar No. 0000-0003-2353-6521 June 2020 INTERNET ADDICTION AND THE RELATIONSHIP TO SELF AND INTERPERSONAL FUNCTIONING WITHIN THE ALTERNATIVE MODEL FOR PERSONALITY DISORDERS (AMPD): IMPLICATIONS FOR PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT This dissertation, by Lori Woehler, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Seattle in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: ___________________________________________ Christopher L. Heffner, PsyD, PhD Chairperson ___________________________________________ Michael J. Sakuma, PhD ___________________________________________ Jeffrey E. Hansen, PhD ___________________________________________ Date ii Copyright © 2020 by Lori L. Woehler All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT INTERNET ADDICTION AND THE RELATIONSHIP TO SELF AND INTERPERSONAL FUNCTIONING WITHIN THE ALTERNATIVE MODEL FOR PERSONALITY DISORDERS (AMPD): IMPLICATIONS FOR PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Lori L. Woehler Antioch University Seattle Seattle, WA Internet addictive use inclusive of inextricably interconnected mobile devices, applications, and social media predicts diminished Self and Interpersonal -

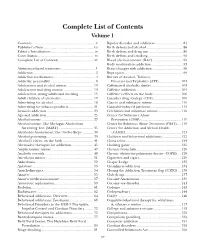

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents .....................................................................v Bipolar disorder and addiction .............................. 84 Publisher’s Note .......................................................vii Birth defects and alcohol ....................................... 86 Editor’s Introduction ............................................... ix Birth defects and drug use ..................................... 89 Contributors ............................................................. xi Birth defects and smoking ...................................... 90 Complete List of Contents ......................................xv Blood alcohol content (BAC) ................................ 92 Body modification addiction .................................. 93 Abstinence-based treatment ..................................... 1 Brain changes with addiction ................................. 96 Addiction ................................................................... 2 Bupropion ............................................................... 99 Addiction medications .............................................. 4 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Addictive personality ................................................ 8 Firearms and Explosives (ATF) ....................... 101 Adolescents and alcohol misuse............................. 10 Caffeinated alcoholic drinks ................................ 103 Adolescents and drug misuse ................................. 13 Caffeine addiction ............................................... -

Computer Game Addiction and Emotional Dependence

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 Computer Game Addiction and Emotional Dependence Amy W. Poon Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Poon, Amy W., "Computer Game Addiction and Emotional Dependence". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/253 Running Head: COMPUTER GAME ADDICTION Poon 1 Computer Game Addiction and Emotional Dependence Amy Poon Trinity College Fall 2011-Spring 2012 Running Head: COMPUTER GAME ADDICTION Poon 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Professor Lee for allowing me to conduct my research on Computer Game Addiction, even when it seemed like such a laughable subject. He helped me get IRB approval, conduct the study, and write a thesis, all the while believing that I could finish it all. I am happy to report that he was right. I would also like to thank Professor Chapman, her long hours with me in the library culminated in my results section. Without her patience and guidance, completing this paper would have been impossible. Finally, I would like to acknowledge Jonathan Handali for proofreading my paper. Abstract As computer games grow in popularity, the negative effects of usage should be studied. Computer games (games played on a computer, tablet, or any web-enabled device) have salient qualities, especially MMORPGs, that cause addictive symptoms. I investigated computer game addiction and usage in Trinity College students. A sample of 114 students (M =20.4 years of age, 61% female) was divided into a non-addicted, social player, and computer-addicted group based on Young's Diagnostic Questionnaire. -

Parents Vs Peers' Influence on Teenagers' Internet Addiction And

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Parents vs peers’ influence on teenagers’ Internet addiction and risky online activities Soh, Patrick Chin‑Hooi; Chew, Kok Wai; Koay, Kian Yeik; Ang, Peng Hwa 2017 Soh, P. C.‑H., Chew, K. W., Koay, K. Y., & Ang, P. H. (2018). Parents vs peers’ influence on teenagers’ Internet addiction and risky online activities. Telematics and Informatics, 35(1), 225‑236. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.11.003 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/84844 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.11.003 © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. This paper was published in Telematics and Informatics and is made available with permission of Elsevier Ltd. Downloaded on 01 Oct 2021 05:40:20 SGT Parents vs Peers’ Influence on teenagers’ Internet Addiction and Risky Online Activities Patrick Chin-Hooi Soh1, Kok Wai Chew1, Kian Yeik Koay1, Peng Hwa Ang2 1Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, Malaysia 2Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Abstract An integral part of the daily lives of adolescents revolves around the Internet. Adolescents are vulnerable online because of a combination of their natural innocence, sensation-seeking drive coupled with the current digital media landscape and its manifold affordances for interactivity, immersive virtual environments and social networking. Adolescence is a time of transition in which youths progressively venture from the safety of the home to explore new opportunities. In this phase of life, both parents and peers play a critical role in either instigating or mitigating risky and dangerous activities. -

INTERNET ADDICTION: Is the Internet a “Pathological Agent” Includable As a Disorder Separate from Other Psychiatric Diagnoses?1

JAD/2003 JOURNAL OF ADDICTIVE DISORDERS INTERNET ADDICTION: Is the Internet a “pathological agent” includable as a disorder separate from other psychiatric diagnoses?1 SUMMARY An examination of whether the Internet is a “pathological agent” and should be included as a disorder separate from other psychiatric diagnoses, including discussion of Internet overuse, the distinction between addictions, compulsions and impulses, technology as a non-chemical addiction, symptoms suggesting addiction potential of the Internet, the prevalence and demographic profile of addicts, uniqueness of the etiology, contrary theories, and placement of the pathological Internet use within the DSM IV. ARTICLE Defining Internet Overuse In 1994, Dr. Kimberly S. Young, an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh, Bradford, received an urgent telephone call from a friend (Young, 1998). Between sobs, the woman told her that she was about to divorce her husband. When asked why, the woman replied, “ he’s addicted to the Internet.” Having piqued her interest, Dr. Young devised a simple eight-question survey from criteria used to assess alcoholism and compulsive gambling. She posted the questionnaire on several Internet user groups on a given day in November 1994, she says, “expecting a handful of responses, and none as dramatic as her friend’s story.” (Young, 1998, p. 4) The following day she had received 40 responses from all over the world, with many claiming they were addicted to the Internet. From this simple survey, followed by her subsequent research, publications, and her presentation at the 104th annual meeting of the American Psychological Association in 1996, (Young, 1996a), there rose a social issue being pursued by dozens of researchers and writers from that time to present day.