How They Won Rugby World Cup Through Height, Mass and Collective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transforming the Springboks: Re-Imagining the South African Nation Through Sport

This paper is a post-print of an article published in Social Dynamics 29:1 (2003): 27-48. The definitive version is available at: http://www.africanstudies.uct.ac.za/downloads/29_1farquharson.zip Transforming the Springboks: Re-imagining the South African Nation through Sport 1 Karen Farquharson and Timothy Marjoribanks Abstract Nation-building occurs not only through the creation of formal institutions, but also through struggles in cultural and symbolic contexts. In apartheid South Africa, the rugby union Springboks both symbolised and institutionalised a racially based form of ‘bounded citizenship’. In post-apartheid South Africa, the Springboks have emerged as a contested and significant site in the attempt to build a non-racial nation through reconciliation. To explore these contests, we undertook a qualitative thematic analysis of newspaper discourses around the Springboks, reconciliation and nation-building in the contexts of the 1995 and 1999 Rugby World Cups. Our research suggests, first, that the Springboks have been re-imagined in newspaper discourses as a symbol of the non-racial nation-building process in South Africa, especially in ‘media events’ such as the World Cup. Second, we find that there are significant limitations in translating this symbolism into institutionalised practice, as exemplified by newspaper debates over the place of ‘merit’ in international team selection processes. We conclude that the media framing of the role of the Springboks in nation-building indicates that unless the re-imagination of the Springboks is accompanied by a transformation in who is selected to represent the team, and symbolically the nation, the Springboks’ contribution to South African nation-building will be over. -

Rugby World Cup Quiz

Rugby World Cup Quiz Round 1: Stats 1. The first eight World Cups were won by only four different nations. Which of the champions have only won it once? 2. Which team holds the record for the most points scored in a single match? 3. Bryan Habana and Jonah Lomu share the record for the most tries in the final stages of Rugby World Cup Tournaments. How many tries did they each score? 4. Which team holds the record for the most tries in a single match? 5. In 2011, Welsh youngster George North became the youngest try scorer during Wales vs Namibia. How old was he? 6. There have been eight Rugby World Cups so far, not including 2019. How many have New Zealand won? 7. In 2003, Australia beat Namibia and also broke the record for the largest margin of victory in a World Cup. What was the score? Round 2: History 8. In 1985, eight rugby nations met in Paris to discuss holding a global rugby competition. Which two countries voted against having a Rugby World Cup? 9. Which teams co-hosted the first ever Rugby World Cup in 1987? 10. What is the official name of the Rugby World Cup trophy? 11. In the 1995 England vs New Zealand semi-final, what 6ft 5in, 19 stone problem faced the English defence for the first time? 12. Which song was banned by the Australian Rugby Union for the 2003 World Cup, but ended up being sang rather loudly anyway? 13. In 2003, after South Africa defeated Samoa, the two teams did something which touched people’s hearts around the world. -

Economic Significance of Tourism and of Major Events: Analysis, Context and Policy Calvin Jones ’ UMI Number: U206081

Economic significance of tourism and of major events: analysis, context and policy Calvin Jones ’ UMI Number: U206081 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U206081 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ca r d if f UNIVFRSITY PR I i YSG OF CA‘ RD W BINDING SERVICES Tel +44 (0)29 2087 4949 Fax +44 (0)29 20371921 e-mail [email protected] Sum m ary The papers presented in this Thesis focus upon the analysis of recreational and sporting activity as economic phenomena. They link the analysis of tourism and sport to wider public policy and economic development debates, applying economic analytical techniques to sport and leisure in a novel manner and charting the development of new tools which enhance our understanding of the economic contribution of these important activities. A number of the papers contained here focus on the extent to which sporting and leisure activity can further regional and national governments' aspirations for economic development, and at what cost. Two of the papers refine economic impact methodologies to better account for the impacts of discrete sporting and cultural events or facilities, using a high level of primary input data, and placing of the results firmly within the local economic development context. -

November 2014

FREE November 2014 OFFICIAL PROGRAMME www.worldrugby.bm GOLF TouRNAMENt REFEREEs LIAIsON Michael Jenkins Derek Bevan mbe • John Weale GROuNds RuCK & ROLL FRONt stREEt Cameron Madeiros • Chris Finsness Ronan Kane • Jenny Kane Tristan Loescher Michael Kane Trevor Madeiros (National Sports Centre) tEAM LIAIsONs Committees GRAPHICs Chief - Pat McHugh Carole Havercroft Argentina - Corbus Vermaak PREsIdENt LEGAL & FINANCIAL Canada - Jack Rhind Classic Lions - Simon Carruthers John Kane, mbe Kim White • Steve Woodward • Ken O’Neill France - Marc Morabito VICE PREsIdENt MEdICAL FACILItIEs Italy - Guido Brambilla Kim White Dr. Annabel Carter • Dr. Angela Marini New Zealand - Brett Henshilwood ACCOMMOdAtION Shelley Fortnum (Massage Therapists) South Africa - Gareth Tavares Hilda Matcham (Classic Lions) Maureen Ryan (Physiotherapists) United States - Craig Smith Sue Gorbutt (Canada) MEMbERs tENt TouRNAMENt REFEREE AdMINIstRAtION Alex O'Neill • Rick Evans Derek Bevan mbe Julie Butler Alan Gorbutt • Vicki Johnston HONORARy MEMbERs CLAssIC CLub Harry Patchett • Phil Taylor C V “Jim” Woolridge CBE Martine Purssell • Peter Kyle MERCHANdIsE (Former Minister of Tourism) CLAssIC GAs & WEbsItE Valerie Cheape • Debbie DeSilva Mike Roberts (Wales & the Lions) Neil Redburn Allan Martin (Wales & the Lions) OVERsEAs COMMENtARy & INtERVIEWs Willie John McBride (Ireland & the Lions) Argentina - Rodolfo Ventura JPR Williams (Wales & the Lions) Hugh Cahill (Irish Television) British Isles - Alan Martin Michael Jenkins • Harry Patchett Rodolfo Ventura (Argentina) -

2021 Major Sports Events Calendar Last Update: January 2021

2021 Major Sports Events Calendar Last update: January 2021 AMERICAN FOOTBALL Throughout 2021 National Football League - - Throughout 2021 NCAA Men's Football - - 7 Feb Super Bowl LV - TBC NFL International Series - - ATHLETICS Throughout 2021 IAAF Diamond League - - 5-7 Mar European Athletics Indoor Championship - - - 26 Sep Berlin Marathon 3 Oct London Marathon TBC 10 Oct Chicago Marathon TBC TBC 17 Oct Paris Marathon - 17 Oct Tokyo Marathon TBC 7 Nov New York Marathon TBC TBC Boston Marathon TBC TBC BASEBALL Throughout 2021 MLB regular season - - 20-30 Aug Little League World Series - - - October MLB World Series TBC BASKETBALL Throughout 2021 NBA regular season - Throughout 2021 NCAA Men's Basketball - - TBD NCAA Women’s Basketball Postseason - - 28-30 May EuroLeague Final Four - - May-July NBA Playoffs - COMBAT Throughout 2021 MMA and UFC Title Fights - Throughout 2021 Boxing World Title Fights - This calendar is for editorial planning purposes only and subject to change For a real-time calendar of coverage, visit reutersconnect.com/planning CRICKET Throughout 2021 Test matches - - Aug-Sep Test matches - England v India Throughout 2021 ODI matches - - TBC Throughout 2021 T20 matches - - - Oct-Nov ICC Men's T20 Cricket World Cup TBC CYCLING 8-30 May Giro D'Italia TBC 26 Jun - 18 Jul Tour de France 14 Aug - 5 Sep La Vuelta 19-26 Sep UCI Road Cycling World Championships - TBC TBC 13-17 Oct UCI Track Cycling World Championships - TBC TBC Throughout 2021 Top international races - ESPORTS Throughout 2021 Call of Duty League - - - Throughout 2021 DOTA 2 - - - TBC DOTA 2 - The International 10 TBC - - Throughout 2021 ESL One & IEM Tournaments TBC - - TBC FIFAe major competitions TBC - - Throughout 2021 League of Legends - - - TBC League of Legends World Championship TBC - - Throughout 2021 NBA2K League - - - Throughout 2021 Overwatch League - - - GOLF Throughout 2021 PGA TOUR Throughout 2021 European Tour - - - Throughout 2021 LPGA Tour TBC TBC - 8-11 April Masters - TBC 20-23 May PGA Championship - TBC 17-20 Jun U.S. -

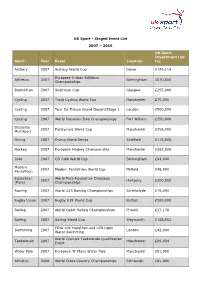

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

UK Sport - Staged Event List

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

OCTOBER 2019 TIME TABLE 10 2019.10.1 ▶ 10.31 J SPORTS 2 ★ First on Air

OCTOBER 2019 TIME TABLE 10 2019.10.1 ▶ 10.31 J SPORTS 2 ★ First On Air Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4.00 Blank 4.00 Blank 4.00 Blank 4.00 Blank 4.00 Cycle* Warera World #5 10.30 Rugby World Cup Daily News 4.00 Blank 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News◇World Rugby #39 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News 4.30 Documentary -The REAL- 11.00 WWE RAW #1374 HL 6.00 Rugby World Cup Daily News 6.30 Mobil 1 The Grid #17 6.30 Rugby World Cup #2 Weekly HL 7.00 Foot!◇J SPORTS HOOP! #10 6.30 Cycle* Warera World #5 5.30 Rugby World Cup Daily News 0.00 Documentary -The REAL- 6.30 Daily Soccer News Foot! 7.00 Foot!◇World Rugby #39 7.30 Daily Soccer News Foot! 8.00 Kanto University Basketball Rookies' Tornament 7.00 Foot!◇FIBA 3x3 World Tour HL 6.00★MLB Post Season 1.00 MLB Players #6 7.30 Documentary -The REAL- 8.00 Nippon Sport Science Basketball 8.00 The 68th Kanto Collegiate Basketball Semifinal-1「Tokai Univ. vs. 8.00 Kanto University Basketball Rookies' Division Series 1.10★Rugby World Cup 8.30★MLB Post Season Selection Ranking match Tournament 5th place decision Nippon Sport Science Univ.」 Tornament 3rd place decision NLDS-A Game2(10/04) Japan Report Pool B Division Series 「Nippon Sport Science Univ vs. -

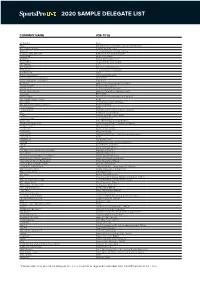

2020 Sample Delegate List

2020 SAMPLE DELEGATE LIST COMPANY NAME JOB TITLE 23 Capital CEO AEG Executive Vice President, Global Partnerships AFC Bournemouth Commercial Director Amazon Head of Sports EU, Prime Video Amazon Web Services Enterprise Account Manager Arsenal FC Head of Content AS Roma Digital Media Manager Aston Villa Head of Data and Insight ATP Media CTO AVL Racing Director of Motorsports BBC Sport Head of Radio and Digital Brentford FC CEO British Gymnastics Commercial Director British Horseracing Authoriy Head of IT British Volleyball Federation President BT Sport Head of Commercial Sports Rights Cardiff City FC Head of TV & Video Chelsea FC Head of Digital Platforms City Football Group Head of Operations Development Comcast EVP/COO DAZN Group Chief Business Development Officer DFL Digital Sports GmbH CEO Discovery VP Digital Content Strategy EFL (English Football League) Head of Digital Eleven Sports COO England Golf Marketing & Communications Director ESL Chief Executive Officer ESPN Commercial Director, EMEA European Tour Head of Content Eurosport SVP Technology and Operations Everton Football Club Chief Financial and Commercial Officer FC Barcelona Marketing Director Facebook Sports Partnerships Formula E Head of Insight Formula One Managing Director - Commercial Operations Fulham FC CEO GB Boxing Chief Executive Google Industry Manager, Sports & Fashion Hookit Chief Revenue Officer IBM Chief Strategy Officer ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup 2019 Managing Director Intel Sports Managing Director International Paralympic Committee Digital Media Manager -

War Metaphors in Newspaper Coverage of the 2010 World Cup

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications WORLD CUP OR WORLD WAR? WAR METAPHORS IN NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF THE 2010 WORLD CUP A Thesis in Media Studies by Daniel DeIuliis © 2011 Daniel DeIuliis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2011 ii The thesis of Daniel DeIuliis was reviewed and approved* by the following: Marie Hardin Associate Professor of Communications Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research Head of the Graduate Program Thesis Advisor Ford Risley Professor of Communications Matt McAllister Professor of Communications *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT By depicting violence and aggression as not only acceptable, but also exciting, rewarding and expected, both visual and print media have consistently employed militaristic metaphors in their coverage of and commentary on sports, particularly international soccer. Although the 2010 World Cup received more online coverage and viewership than any major sporting event in history, the event - and the militaristic overtones of its media coverage - has received little academic attention, even at a time when many of the tournament‟s participants are engaged in violent conflicts both domestically and abroad. To determine the extent of the explicit use of military terminology in the newspaper coverage of the 2010 World Cup, in what context they were used, and how these contexts reinforce traditional notions of hegemonic masculinity and nationalism, this research employed a preliminary content analysis of print newspaper coverage of the 2010 World Cup from The New York Times, The Sunday Times of South Africa and The London Times of Great Britain. -

Rugby & Football Memorabilia

RUGBY & FOOTBALL MEMORABILIA Day One: Wednesday 9th December at 10.00am Rugby Union and Rugby League Memorabilia (Lots 1-441) Day Two: Thursday 10th December at 10.00am Football Memorabilia (Lots 442-970) **LIVE ONLINE AUCTION – ONLY** To bid LIVE, please click the BID LIVE tab on Mullocks homepage at www.mullocksauctions.co.uk and follow link and instructions. Using your ‘TheSaleroom’ login username and password THIS WILL REDUCE THE INTERNET SURCHAGE TO 3% PLUS VAT You can also watch, listen and bid LIVE directly via www.thesaleroom.com but the INTERNET SURCHARGE is 4.95% plus VAT We also accept Commission Bids, please see terms and condition on Page 3. All lots are fully described and illustrated at www.mullocksauctions.co.uk and www.thesaleroom.com Making and Preserving History The Old Shippon, Wall-under-Heywood, Church Stretton, Shropshire SY6 7DS Tel: 01694 771771 Email: [email protected] Conditions of Sale The highest bidder shall be The Purchaser, subject to the right of the Vendor to bid and the right of the Auctioneers to reject any bidding. If any dispute arises between two or more bidders, such dispute shall be finally settled by the Auctioneers, or at their discretion the Lot may be resold. The Auctioneers have the full power to withdraw or alter any lot or lots he may think proper. The bidding will be regulated by the Auctioneers. No bidding shall be retracted. The Auctioneers act as agents only. Each lot, as set out in the Catalogue or as divided or joined with any Lot or Lots at the Sale at the sole discretion of the Auctioneers, is sold with all faults, imperfections and errors of descriptions, and neither the Vendors nor the Auctioneers are responsible for the authenticity, attribution, genuineness, origin, authorship, date, age, period, condition of quality of any lot. -

Rugby, Traditions and Destination Image

RUGBY, TRADITIONS AND DESTINATION IMAGE An empirical analysis of the influence that the inclusion of the sporting heritage of a destination into its tourism strategy can have to attract tourists to a specific sport event Author: Lucas Fernández Estévez Supervisor: William C. Gartner Faculty of Humanities, University of Southern Denmark Faculty of Economics, University of Ljubljana Faculty of Tourism, University of Girona University of Ljubljana, 31st July 2014 AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT The undersigned _____________________, a student at the University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Economics, (hereafter: FELU), declare that I am the author of the bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation entitled _________________________________________________________________, written under supervision of _______________________________________________ and co-supervision of _________________________________________. In accordance with the Copyright and Related Rights Act (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, Nr. 21/1995 with changes and amendments) I allow the text of my bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation to be published on the FELU website. I further declare the text of my bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation to be based on the results of my own research; the text of my bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation to be language-edited and technically in adherence with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works which means that I o cited and / or quoted works and opinions