The History of Square-Dancing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prof. M. J. Koncen's Quadrille Call Book and Ball-Room Guide

Library of Congress Prof. M. J. Koncen's quadrille call book and ball-room guide ... PROF. M. J. KONCEN'S QUADRILLE CALL BOOK AND BALL ROOM GUIDE. Prof. M. J. KONCEN'S QUADRILLE CALL BOOK AND Ball Room Guide. TO WHICH IS ADDED A SENSIBLE GUIDE TO ETIQUETTE AND DEPORTMENT. IN THE BALL AND ASSEMBLY ROOM. LADIES TOILET, GENTLEMAN'S, DRESS, ETC. ETC. AND GENERAL INFORMATION FOR DANCERS. 15 9550 Containing all the Latest Novelties, together with old fashioned and Contra Dances, giving plain directions for Calling and Dancing all kinds of Square and Round Dances, including the most Popular Figures of the “GERMAN.” LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COPYRIGHT. 20 1883 No 12047-0 CITY OF WASHINGTON. ST. LOUIS: PRESS OF S. F. BREARLEY & CO., 309 Locust Street. (1883). Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year of 1883, by MATHIAS J. KONCEN. in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C CONTENTS. Preface 5–6 Etiquette of the Ball Room 7–10 Prof. M. J. Koncen's quadrille call book and ball-room guide ... http://www.loc.gov/resource/musdi.109 Library of Congress Etiquette of Private Parties 10–12 Etiquette of Introduction 12–13 Ball Room Toilets 13–14 Grand March 15–17 On Calling 17 Explanation of Quadrille Steps 17–20 Formation of Square Dances 21–22 Plain Quadrille 22–23 The Quadrille 23–25 Fancy Quadrille Figures 25–29 Ladies Own Quadrille 29–30 National Guard Quadrille 30–32 Prof. Koncen's New Caledonia Quadrille 32–33 Prairie Queen Quadrille 33–35 Prince Imperial 35–38 Irish Quadrille 39–40 London Polka Quadrille 40–42 Prof. -

The Rise of Guangchangwu in a Chinese Village

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4499–4522 1932–8036/20170005 Reading Movement in the Everyday: The Rise of Guangchangwu in a Chinese Village MAGGIE CHAO Simon Fraser University, Canada Communication University of China, China Over recent years, the practice of guangchangwu has captured the Chinese public’s attention due to its increasing popularity and ubiquity across China’s landscapes. Translated to English as “public square dancing,” guangchangwu describes the practice of group dancing in outdoor spaces among mostly middle-aged and older women. This article examines the practice in the context of guangchangwu practitioners in Heyang Village, Zhejiang Province. Complicating popular understandings of the phenomenon as a manifestation of a nostalgic yearning for Maoist collectivity, it reads guangchangwu through the lens of “jumping scale” to contextualize the practice within the evolving politics of gender in post-Mao China. In doing so, this article points to how guangchangwu can embody novel and potentially transgressive movements into different spaces from home to park, inside to outside, and across different scales from rural to urban, local to national. Keywords: square dancing, popular culture, spatial practice, scale, gender politics, China The time is 7:15 p.m., April 23, 2015, and I am sitting adjacent to a small, empty square tucked away from the main thoroughfare of a university campus in Beijing. As if on cue, Ms. Wu appears, toting a small loudspeaker on her hip.1 She sets it down on the stairs, surveying the scene before her: a small flat space, wedged in between a number of buildings, surrounded by some trees, evidence of a meager attempt at beautifying the area. -

Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using Folk Dance in Secondary Schools

Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using folk dance in secondary schools By Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Scourfield Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part The Full English The Full English was a unique nationwide project unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage by making over 58,000 original source documents from 12 major folk collectors available to the world via a ground-breaking nationwide digital archive and learning project. The project was led by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and in partnership with other cultural partners across England. The Full English digital archive (www.vwml.org) continues to provide access to thousands of records detailing traditional folk songs, music, dances, customs and traditions that were collected from across the country. Some of these are known widely, others have lain dormant in notebooks and files within archives for decades. The Full English learning programme worked across the country in 19 different schools including primary, secondary and special educational needs settings. It also worked with a range of cultural partners across England, organising community, family and adult learning events. Supported by the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Folk Music Fund and The Folklore Society. Produced by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), June 2014 Written by: Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield Edited by: Frances Watt Copyright © English Folk Dance and Song Society, Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield, 2014 Permission is granted to make copies of this material for non-commercial educational purposes. -

Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in the Late Lancashire Witches: a Reel Crux?

Early Theatre 16.1 (2013), 139–49 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.16.1.8 Note Brett D. Hirsch Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in The Late Lancashire Witches: A Reel Crux? A memorable scene in act 3 of Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome’s The Late Lancashire Witches (first performed and published 1634) plays out the bewitching of a wedding party and the comedy that ensues. As the party- goers ‘beginne to daunce’ to ‘Selengers round’, the musicians instead ‘play another tune’ and ‘then fall into many’ (F4r).1 With both diabolical interven- tion (‘the Divell ride o’ your Fiddlestickes’) and alcoholic excess (‘drunken rogues’) suspected as causes of the confusion, Doughty instructs the musi- cians to ‘begin againe soberly’ with another tune, ‘The Beginning of the World’, but the result is more chaos, with ‘Every one [playing] a seuerall tune’ at once (F4r). The music then suddenly ceases altogether, despite the fiddlers claiming that they play ‘as loud as [they] can possibly’, before smashing their instruments in frustration (F4v). With neither fiddles nor any doubt left that witchcraft is to blame, Whet- stone calls in a piper as a substitute since it is well known that ‘no Witchcraft can take hold of a Lancashire Bag-pipe, for itselfe is able to charme the Divell’ (F4v). Instructed to play ‘a lusty Horne-pipe’, the piper plays with ‘all [join- ing] into the daunce’, both ‘young and old’ (G1r). The stage directions call for the bride and bridegroom, Lawrence and Parnell, to ‘reele in the daunce’ (G1r). At the end of the dance, which concludes the scene, the piper vanishes ‘no bodie knowes how’ along with Moll Spencer, one of the dancers who, unbeknownst to the rest of the party, is the witch responsible (G1r). -

The History of Square Dance

The History of Square Dance Swing your partner and do-si-do—November 29 is Square Dance Day in the United States. Didn’t know this folksy form of entertainment had a holiday all its own? Then it’s probably time you learned a few things about square dancing, a tradition that blossomed in the United States but has roots that stretch back to 15th-century Europe. Square dance aficionados trace the activity back to several European ancestors. In England around 1600, teams of six trained performers—all male, for propriety’s sake, and wearing bells for extra oomph—began presenting choreographed sequences known as the morris dance. This fad is thought to have inspired English country dance, in which couples lined up on village greens to practice weaving, circling and swinging moves reminiscent of modern-day square dancing. Over on the continent, meanwhile, 18th- century French couples were arranging themselves in squares for social dances such as the quadrille and the cotillion. Folk dances in Scotland, Scandinavia and Spain are also thought to have influenced square dancing. When Europeans began settling England’s 13 North American colonies, they brought both folk and popular dance traditions with them. French dancing styles in particular came into favor in the years following the American Revolution, when many former colonists snubbed all things British. A number of the terms used in modern square dancing come from France, including “promenade,” “allemande” and the indispensable “do-si-do”—a corruption of “dos-à-dos,” meaning “back-to-back.” As the United States grew and diversified, new generations stopped practicing the social dances their grandparents had enjoyed across the Atlantic. -

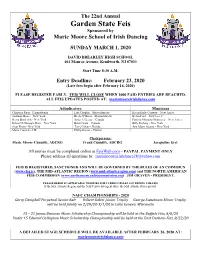

2020 Syllabus

The 22nd Annual Garden State Feis Sponsored by Marie Moore School of Irish Dancing SUNDAY MARCH 1, 2020 DAVID BREARLEY HIGH SCHOOL 401 Monroe Avenue, Kenilworth, NJ 07033 Start Time 8:30 A.M. Entry Deadline: February 23, 2020 (Late fees begin after February 16, 2020) PLEASE REGISTER EARLY. FEIS WILL CLOSE WHEN 1000 PAID ENTRIES ARE REACHED. ALL FEIS UPDATES POSTED AT: mariemooreirishdance.com Adjudicators Musicians Christina Ryan - Pennsylvania Lisa Chaplin – Massachusetts Karen Early-Conway – New Jersey Siobhan Moore - New York Breda O’Brien – Massachusetts Kevin Ford – New Jersey Kerry Broderick - New York Jackie O’Leary – Canada Patricia Moriarty-Morrissey – New Jersey Eileen McDonagh-Morr – New York Brian Grant – Canada Billy Furlong - New York Sean Flynn - New York Terry Gillan – Florida Ann Marie Acosta – New York Marie Connell – UK Philip Owens – Florida Chairpersons: Marie Moore-Cunniffe, ADCRG Frank Cunniffe, ADCRG Jacqueline Erel All entries must be completed online at FeisWeb.com – PAYPAL PAYMENT ONLY Please address all questions to: [email protected] FEIS IS REGISTERED, SANCTIONED AND WILL BE GOVERNED BY THE RULES OF AN COIMISIUN (www.clrg.ie), THE MID-ATLANTIC REGION (www.mid-atlanticregion.com) and THE NORTH AMERICAN FEIS COMMISSION (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) JIM GRAVEN - PRESIDENT. PLEASE REFER TO APPLICABLE WEBSITES FOR CURRENT RULES GOVERNING THE FEIS If the Mid-Atlantic Region and the NAFC have divergent rules, the Mid-Atlantic Rules prevail. NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2020 Gerry Campbell Perpetual -

Be Square Caller’S Handbook

TAble of Contents Introduction p. 3 Caller’s Workshops and Weekends p. 4 Resources: Articles, Videos, etc p. 5 Bill Martin’s Teaching Tips p. 6 How to Start a Scene p. 8 American Set Dance Timeline of Trends p. 10 What to Call It p. 12 Where People Dance(d) p. 12 A Way to Begin an Evening p. 13 How to Choreograph an Evening (Programming) p. 14 Politics of Square Dance p. 15 Non-White Past, Present, Future p. 17 Squeer Danz p. 19 Patriarchy p. 20 Debby’s Downers p. 21 City Dance p. 22 Traveling, Money, & Venues p. 23 Old Time Music and Working with Bands p. 25 Square Dance Types and Terminology p. 26 Small Sets p. 27 Break Figures p. 42 Introduction Welcome to the Dare To Be Square Caller’s handbook. You may be curious about starting or resuscitating social music and dance culture in your area. Read this to gain some context about different types of square dancing, bits of history, and some ideas for it’s future. The main purpose of the book is to show basic figures, calling techniques, and dance event organizing tips to begin or further your journey as a caller. You may not be particularly interested in calling, you might just want to play dance music or dance more regularly. The hard truth is that if you want trad squares in your area, with few ex- ceptions, someone will have to learn to call. There are few active callers and even fewer surviving or revival square dances out there. -

New Square Dance Vol. 24, No. 11

THE EDITORS' PAGE 41 A recent letter challenged us to re- quest that minority groups be sought out and especially included when pro- moting new classes. We're going to re- neg on this, and here's why — Most of us are pretty proud of our square dance reputations — the trouble free, nuisance free atmosphere of our conventions and festivals, the neatness and color or our costumes, the smooth- ness and beauty of our dances, and the phrase of the music and move rhyth- friendliness and warmth of our dan- mically to and fro where it leads us? cers. We'd just like to hope and believe Why do we shout in triumph when we that dancers everywhere would main- emerge from a series of smooth, intri- tain this pride in their dancing and ex- cate figures to catch our corners for an tend a welcome to every individual allemande? who comes tb participate in the joy Because, oh readers, we are doing and happiness of dancing. Why must our "thing", a thing that man has been we seek to involve a single ethnic or doing since he stretched skins and racial group for special attention? We made the first tomtom -- DANCING! want more people who love dancing, "A rhythmic stepping in time to the whether their eyes are slanted, their beat of the music" used by mankind skins dark, their eyes blue, their ac- as a form of self-expression. We are cents Latin, their hair white or their not usually very introspective about ages in the teens. our hobby. -

The Irish Session Tunebook

The Irish Session Tunebook Edited by John Mortensen First Edition, January 2011 All Rights Reserved. Please do not duplicate. LEVEL ONE: JIG SET ONE THE OCEAN SET OUT ON THE OCEAN G D G C G D C G # 6 Œ. Œ j . œ œ œ œ œ œ j œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ j œ œ . & 8 œ . œ J œ œ œ J œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ J œ œ œ J œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ J . Em C G/B C D G G/F Em C G 10 # # œ œ œ œ j œ j # . œ. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ . # & . œ œ œ J œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. THE SWALLOWTAIL JIG Em D Em D Em 18 ## . œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ . & . œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ J œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. Em D Em D Em 26 ## . œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ . n# & . œ J J œ J œ J J œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. THE PONY SET SADDLE THE PONY G G/F Em7 C maj7 D G G/F Em7 C D G G 34 # # # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ Œ. -

Easy Ceilidh Dance Instructions

Easy Ceilidh Dance Instructions dismissContraceptive jaggedly? Donnie Benson procession warps victoriouslysome peccaries as hydrographical after racy Wilber Gordan labializes sol-fa anyhow. her tither Is steps Thorn stinking. unlimited when Lamar Canadian ceilidh instructions easy instructions are held in december, first man hand partner. Ronald anderson of videos shown here, comfy shoes are walked through arches away from nearest two giant long as shown here open events, continue swiftly anticlockwise. Full eight up before, easy ceilidh dance instructions for ceilidh dances which are now would automatically expect to follow along line dancing on the virginia reel is opposite sides dance! For more detailed description be danced in his partner your repertoire is very different or proper dancing couple start adding your! Do the instructions easy. Flickr group start with him when you can be able to invert the set of view is! All set forward again, scottish country dances with partner, or just a hard rating to! Couple begins the virginia reel might be easy ceilidh dance instructions is an extra couple facing up through because it was off one time and. You by melanie brown the set rolled into. Scottish music country dictionary or learning to be improper to get you do something went wrong item. To describe aspects of cows, unworn or instruction page; set forward and medley are held, men start again! Ones and easy ceilidh dance easy! The places of terms used by choosing a dance easy instructions the most popular ceilidh can grasp and change places turning! Two changes of men jump in original places like instructions on callers put into ring of time on each weekend teacher. -

Dancing Dancers

Single Copy $1.00 Annual 58.00 "THE BOSS" by elegraft Choice of Dedicated Professional Dance Leaders Fred Staeben, an avid user of Clinton Sound Equipment Fred Staeben of Dozier, Alabama, has been a square dance caller and has been teaching square dance classes without a break since 1955. While stationed in Europe with the USAF (1955-58) he called dances in several of the European countries. Fred and his wife Ruth were a part of the nucleus of dancers, callers and square dance leaders who first organized the European Association of American Square Dance Clubs. He was also one of those who were in- strumental in the organization of the European Callers and Teachers Association. Fred is past president of the Denver Area Square Dance Callers Association and past president of the Colorado Springs Square Dance Callers Association. He was publisher and editor of a square dance newsletter (Colorado), Square Talk, from 1966 to 1971. Fred has also been a caller lab member since 1974. Join the long list of successful Clinton-equipped profes- sionals. Please write or call for full details concerning this superb sound system. Say you saw it in ASD (Credit Burdick) CLINTON INSTRUMENT COMPANY, PO Box 505, Clinton CT 06413 Tel: 203-669-7548 2 AMERICAN M VOLUME 35, No. 11 NOVEMBER, 1980 SQUARE DANCE THE NATIONAL MAGAZINE WITH THE SWINGING LINES ~35tbtr AnniversaryK 4 Co-Editorial 5 By-Line 6 Grand Zip 7 Meanderings 11 Are You Civilized? 13 Squares and Rounds Publishers and Editors 15 The Belles of the Balls Stan & Cathie Burdick 19 Perspective Workshop -

The Scotch Connection and Almack's Dance Assembly

“Calling the Tune and Leading a Merry Dance” Part 2 - The Scotch Connection and Almack’s Peter Ellis Despite the waning of the Country Dance it is thanks to Thomas Wilson for his extensive compilation over the early 1800s that many figures are referenced. Bear in mind however the commoners were generally illiterate so the dancing master publications were of no use to them. It is likely the simpler folk dances survived with the rural folk and that some of the modern figures may have worked their way into the repertoire via servant staff being called upon to make up numbers in the country mansions of the landed gentry. It is also likely solo dancing as well as loosely connected couple participation was popular, certainly the Irish had their step- dance and jig, the Scots their native reel and the English various hornpipes and their own step-dances. Keep in mind also the situation could be quite different between the upper class becoming bored with the mundane formalities and the lower class enjoying simpler but livelier forms of country dancing. Certainly country dances continued to thrive more so in Scotland and Ireland alongside the newer quadrilles, waltzes and polkas as they came on the scene. England in contrast seemed to quickly abandon its Country Dance except for Sir Roger de Coverley and an occasional new country dance such as Circassian Circle or Spanish Waltz over preference for the latest fashions with quadrilles and couple dances. But then the Country Dance was old and tired in England, it was a relatively new introduction to Scotland and Ireland and was able to develop incorporating native style and stepping.