Academic Licenses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic License

Perl version 5.10.0 documentation - perlartistic NAME perlartistic - the Perl Artistic License SYNOPSIS You can refer to this document in Pod via "L<perlartistic>" Or you can see this document by entering "perldoc perlartistic" DESCRIPTION This is "The Artistic License". It's here so that modules,programs, etc., that want to declare this as their distributionlicense, can link to it. It is also one of the two licenses Perl allows itself to beredistributed and/or modified; for the other one, the GNU GeneralPublic License, see the perlgpl. The "Artistic License" Preamble The intent of this document is to state the conditions under which aPackage may be copied, such that the Copyright Holder maintains somesemblance of artistic control over the development of the package,while giving the users of the package the right to use and distributethe Package in a more-or-less customary fashion, plus the right to makereasonable modifications. Definitions "Package" refers to the collection of files distributed by theCopyright Holder, and derivatives of that collection of files createdthrough textual modification. "Standard Version" refers to such a Package if it has not beenmodified, or has been modified in accordance with the wishes of theCopyright Holder as specified below. "Copyright Holder" is whoever is named in the copyright orcopyrights for the package. "You" is you, if you're thinking about copying or distributing this Package. "Reasonable copying fee" is whatever you can justify on the basisof media cost, duplication charges, time of people involved, and so on.(You will not be required to justify it to the Copyright Holder, butonly to the computing community at large as a market that must bear thefee.) "Freely Available" means that no fee is charged for the itemitself, though there may be fees involved in handling the item. -

License Agreement

TAGARNO MOVE, FHD PRESTIGE/TREND/UNO License Agreement Version 2021.08.19 Table of Contents Table of Contents License Agreement ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Open Source & 3rd-party Licenses, MOVE ............................................................................................................ 4 Open Source & 3rd-party Licenses, PRESTIGE/TREND/UNO ................................................................................. 4 atk ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 base-files ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 base-passwd ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 BSP (Board Support Package) ............................................................................................................................ 5 busybox.............................................................................................................................................................. 5 bzip2 ................................................................................................................................................................. -

Artistic License 2.0

Artistic License 2.0 Copyright (c) 2000-2006, The Perl Foundation. Everyone is permitted to copy and distribute verbatim copies of this license document, but changing it is not allowed. Preamble This license establishes the terms under which a given free software Package may be copied, modified, distributed, and/or redistributed. The intent is that the Copyright Holder maintains some artistic control over the development of that Package while still keeping the Package available as open source and free software. You are always permitted to make arrangements wholly outside of this license directly with the Copyright Holder of a given Package. If the terms of this license do not permit the full use that you propose to make of the Package, you should contact the Copyright Holder and seek a different licensing arrangement. Definitions "Copyright Holder" means the individual(s) or organization(s) named in the copyright notice for the entire Package. "Contributor" means any party that has contributed code or other material to the Package, in accordance with the Copyright Holder's procedures. "You" and "your" means any person who would like to copy, distribute, or modify the Package. "Package" means the collection of files distributed by the Copyright Holder, and derivatives of that collection and/or of those files. A given Package may consist of either the Standard Version, or a Modified Version. "Distribute" means providing a copy of the Package or making it accessible to anyone else, or in the case of a company or organization, to others outside of your company or organization. "Distributor Fee" means any fee that you charge for Distributing this Package or providing support for this Package to another party. -

Promoting Artistic Progress Through the Enforcement of Creative Commons Attribution and Share-Alike Licenses

Florida State University Law Review Volume 36 Issue 4 Article 7 2009 Little Victories: Promoting Artistic Progress Through the Enforcement of Creative Commons Attribution and Share-Alike Licenses Ashley West [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ashley West, Little Victories: Promoting Artistic Progress Through the Enforcement of Creative Commons Attribution and Share-Alike Licenses, 36 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2009) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol36/iss4/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW LITTLE VICTORIES: PROMOTING ARTISTIC PROGRESS THROUGH THE ENFORCEMENT OF CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION AND SHARE-ALIKE LICENSES Ashley West VOLUME 36 SUMMER 2009 NUMBER 4 Recommended citation: Ashley West, Little Victories: Promoting Artistic Progress Through the Enforcement of Creative Commons Attribution and Share-Alike Licenses, 36 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 903 (2009). COMMENT LITTLE VICTORIES: PROMOTING ARTISTIC PROGRESS THROUGH THE ENFORCEMENT OF CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION AND SHARE-ALIKE LICENSES ASHLEY WEST* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 903 II. THE BIRTH AND GROWTH OF THE CREATIVE COMMONS .................................... 906 -

Elements of Free and Open Source Licenses: Features That Define Strategy

Elements Of Free And Open Source Licenses: Features That Define Strategy CAN: Use/reproduce: Ability to use, copy / reproduce the work freely in unlimited quantities Distribute: Ability to distribute the work to third parties freely, in unlimited quantities Modify/merge: Ability to modify / combine the work with others and create derivatives Sublicense: Ability to license the work, including possible modifications (without changing the license if it is copyleft or share alike) Commercial use: Ability to make use of the work for commercial purpose or to license it for a fee Use patents: Rights to practice patent claims of the software owner and of the contributors to the code, in so far these rights are necessary to make full use of the software Place warranty: Ability to place additional warranty, services or rights on the software licensed (without holding the software owner and other contributors liable for it) MUST: Incl. Copyright: Describes whether the original copyright and attribution marks must be retained Royalty free: In case a fee (i.e. contribution, lump sum) is requested from recipients, it cannot be royalties (depending on the use) State changes: Source code modifications (author, why, beginning, end) must be documented Disclose source: The source code must be publicly available Copyleft/Share alike: In case of (re-) distribution of the work or its derivatives, the same license must be used/granted: no re-licensing. Lesser copyleft: While the work itself is copyleft, derivatives produced by the normal use of the work are not and could be covered by any other license SaaS/network: Distribution includes providing access to the work (to its functionalities) through a network, online, from the cloud, as a service Include license: Include the full text of the license in the modified software. -

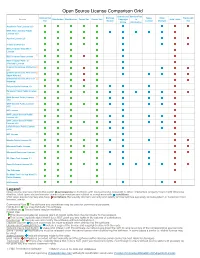

Open Source License Comparison Grid

Open Source License Comparison Grid License and Network Use Commercial Disclose Same State Trademark License Distribution Modification Patent Use Private Use Copyright is Hold Liable Use Source License Changes Use Notice Distribution Academic Free License v3.0 GNU Affero General Public License v3.0 Apache License 2.0 Artistic License 2.0 BSD 2-clause "Simplified" License BSD 3-clause Clear License † BSD 3-clause "New" or "Revised" License Creative Commons Attribution ‡ 4.0 Creative Commons Attribution ‡ Share Alike 4.0 Creative Commons Zero v1.0 ‡ Universal Eclipse Public License 1.0 European Union Public License 1.1 GNU General Public License † v2.0 GNU General Public License v3.0 ISC License GNU Lesser General Public License v2.1 GNU Lesser General Public License v3.0 LaTeX Project Public License v1.3c MIT License † Mozilla Public License 2.0 Microsoft Public License Microsoft Reciprocal License SIL Open Font License 1.1 Open Software License 3.0 The Unlicense Do What The F*ck You Want To Public License zlib License Legend Open source licenses grant to the public permissions to do things with licensed works copyright or other "intellectual property" laws might otherwise disallow. Most open source licenses' grants of permissions are subject to compliance with conditions. Most open source licenses also have limitations that usually disclaim warranty and liability and sometimes expressly exclude patent or trademark from licenses' grants. Commercial Use: This software and derivatives may be used for commercial purposes. Distribution: You may distribute this software. Modification: This software may be modified. Patent Use: This license provides an express grant of patent rights from the contributor to the recipient. -

Download File

Jacobsen v. Katzer: Open Source License Validation — How Far Does It Go? By: Paul H. Arne1,2 On August 13, 2008, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued its opinion in Jacobsen v. Katzer and Kamind Associates, Inc. (d/b/a KAM Industries)3 (“Jacobsen”). By this decision, the Federal Circuit has validated the legal position intended by the creators of some of the most important open source licenses: covenants in an open source license may be enforced under copyright law rather than on contractual grounds. This article will examine the ruling and reasoning in this important case, ask some questions unanswered by this ruling, and discuss some additional implications of this case outside of the open source context. Facts and Procedural History4 Jacobsen and Katzer/Kamind were the developers of competing software applications used to program the decoder chips that control model trains. Jacobsen and others, through an open source group known as JMRI, developed software called DecoderPro. DecoderPro was licensed under an open source license: the Artistic License.5 Katzer/Kamind’s software, Decoder Commander, was presumably developed and licensed under a proprietary license. Katzer obtained patents on certain inventions and then asserted that DecoderPro infringed. In response, Jacobsen filed suit, seeking a declaratory judgment that the patents are unenforceable or not applicable to DecoderPro.6 Earlier, a predecessor or employee of Katzer/Kamind had downloaded DecoderPro and incorporated portions of it into Decoder Commander. Despite using some of the DecoderPro code in its product, Katzer/Kamind did not follow the requirements of the Artistic License. -

Hitachi Infrastructure Analytics Advisor V4.2.0 Open Source Software Packages

Hitachi Infrastructure Analytics Advisor V4.2.0 Open Source Software Packages Contact Information: Hitachi Infrastructure Analytics Advisor Project Manager Hitachi Vantara Corporation 2535 Augustine Drive Santa Clara, California 95054 Name of Product/Product Version License Component ASM 3.3.1 BSD 3-Clause "New" or "Revised" License ASM* 3.3.1(modif BSD 3-Clause "New" or "Revised" License ied) Algorithm::Diff - Compute 1.1903 GNU General Public License Version `intelligent' differences between 1 or Artistic License two files / lists Apache Click 2.3.0 Apache License, Version 2.0 BSD 3-Clause "New" or "Revised" License Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic The License of "Prototype JavaScript framework" The MIT License Apache Commons BCEL 5.1 Apache BCEL License Apache Commons CLI 1.1 Apache License, Version 2.0 Apache Commons Codec 1.10 Apache License, Version 2.0 Apache Commons Collections 3.2 Apache License, Version 2.0 Apache Commons Collections 4.1 Apache License, Version 2.0 Apache Commons Compress 1.0 Apache License, Version 2.0 Apache Commons Email 1.5 Apache License, Version 2.0 Name of Product/Product Version License Component Apache HTTP Server 2.4.34 Apache License, Version 2.0 BSD 3-Clause "New" or "Revised" License GNU General Public License, Version 3 with Autoconf exception Public Domain or Free License without conditions The License by "Bell Communications Research, Inc. (Bellcore)" The License by "Carnegie Mellon University" The License by "RSA Data Security, Inc." The License of "RSA Data Security, Inc. MD4 Message-Digest Algorithm" The License of "RSA Data Security, Inc. -

Jacobsen V. Katzer: Failure of the Artistic License and Repercussions for Open Source Erich M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF LAW & TECHNOLOGY Volume 9 Article 5 Issue 3 Online Issue 10-1-2007 Jacobsen v. Katzer: Failure of the Artistic License and Repercussions for Open Source Erich M. Fabricius Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Erich M. Fabricius, Jacobsen v. Katzer: Failure of the Artistic License and Repercussions for Open Source, 9 N.C. J.L. & Tech. 65 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt/vol9/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF L-xw & TECHNOLOGY 9 NC JOLT ONLINE ED. 65 (2008) JACOBSEN V. KATZER: FAILURE OF THE ARTISTIC LICENSE AND REPERCUSSIONS FOR OPEN SOURCE Erich M. Fabricius' The case of Jacobsen v. Katzer is among the earliest to consider the enforceability of open source software licenses, and is therefore of key interest to the open source community. To the disappointment of that community, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California held that an open source project creator could pursue a breach of contract claim but not a copyright infringement claim against a defendant for violating the project's license terms. -

Open Source Software: What Business Lawyers, Entrepreneurs and IT Professionals Should Know

Open Source Software: What Business Lawyers, Entrepreneurs and IT Professionals Should Know Stuart R. Hemphill Partner Minneapolis P: (612) 340-2734 F: (612) 340-8856 [email protected] © 2016 Dorsey & Whitney LLP Source vs. Object Source Code Object Code Programmer readable statements in Machine readable Binary: a computer language, such as C, C++, Cobol, Fortran, Java, Perl, 000010100010001010 PHP 110001010000010100 000100101010001011 // Create a button and add it to the applet. // Also, set the button's colors clear_button = new Button("Clear"); Or Hexadecimal clear_button.setForeground(Color.black); clear_button.setBackground(Color.lightGray); 3F7A this.add(clear_button); (translates to the following binary number: 0011 1111 0111 1010) 2 History of Open Source Software . Term coined in February 1998 by Silicon Valley insiders in anticipation of Netscape’s announcement that it would release the source code for its browser software . This meant software coders could understand the browser’s working details and potentially modify them . 1998 was a momentous time for open source movement given mainstream adoption of internet . But concept significantly pre-dates coining of term 3 Free Software Foundation . Free Software Foundation (FSF), created in 1983 by Richard Stallman of MIT with goal of developing free version of UNIX operating system; everyone could share and change this version . According to FSF, “‘Free software’ is a matter of liberty, not price … think of ‘free’ as in ‘free speech,’ not as in ‘free beer.’” . Stallman wrote a license leveraging copyright in base code and intended to keep derivatives of base software “free” by requiring source code disclosure . Non-negotiable terms; accept by use . -

JACOBSEN V. KATZER: a NEW DECISION AFFECTING OPEN SOURCE LICENSING by Robert S

IP ADVISOR A N INFORMATIONAL N EWSLETTER FROM G OODWIN PROCTER LLP’S INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY G ROUP ARTICLE FROM NOVEMBER 2007 ISSUE JACOBSEN V. KATZER: A NEW DECISION AFFECTING OPEN SOURCE LICENSING By Robert S. Blasi and Kenda J. Stewart The District Court for the Northern District of California recently ruled in Jacobsen v. Katzer, No. 3:06-cv-01905 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 17, 2007), that the defendant’s alleged failure to adhere to the provisions of an open source license, by distributing copies of the licensed source code without the inclusion of the required the attribution notice, constituted a claim for breach of contract and not a claim for copyright infringement. The plaintiff in the case was Robert Jacobsen, a model train hobbyist and member of the Java Model Railroad Interface Project (“JMRI”). Jacobsen developed model train software made available through the JMRI online community subject to a standard open source software license. Under that license (the “Artistic License”), the licensee receives a nonexclusive license to use, distribute and copy the licensed software. The nonexclusive license is subject to various conditions, notably the licensee’s proper attribution of the author of the licensed software. The defendants were Matthew Katzer and Kamind Associates, Inc. (“KAM”). Katzer is the chief executive officer of KAM, a company that develops software for model railroad enthusiasts. Katzer obtained certain patents relating to model railroad software and sought royalties from Jacobsen and JMRI, on the basis that the patents covered the JMRI software. In March 2006, Jacobsen filed suit alleging that Katzer’s patents were invalid for inequitable conduct before the PTO. -

Dynamic Software Reconciliation 5.0 - Use of Third Party Libraries

Dynamic Software Reconciliation 5.0 - Use of Third Party Libraries Name Selected License pSpreadsheet-ParseXLSX 0.17 (MIT) MIT License (also X11) activestate Perl 5.14 (Other/Commercial) Other/Commercial LWP-Protocol-Connect 6.09 (Perl) PERL Artistic License Net-SSLeay 1.81 (Perl) PERL Artistic License Spreadsheet-ReadSXC 0.20 (Perl) PERL Artistic License Win32-Process-Info 1.022 (Perl) PERL Artistic License date-format 2.30 (Perl) PERL Artistic License pCrypt-Blowfish 2.14 (Systemics License) PERL Artistic License pFile-Find-Rule 0.33 (Perl) PERL Artistic License pHTML-Formatter 2.11 (Perl) PERL Artistic License pIO-Stingy-Scalar 2.11 (Perl) PERL Artistic License pList-More-Utils 0.406 (Perl) PERL Artistic License pRPM-Header-PurePerl 1.0.2 (Perl) PERL Artistic License pSpreadsheet-Read 0.6 (Perl) PERL Artistic License pXML-DOM 1.44 (Perl) PERL Artistic License pXML-EasyOBJ 1.12 (Perl) PERL Artistic License xmltwig 3.49 (Perl) PERL Artistic License Dynamic Software Reconciliation 5.0 - Third-Party Notices Report [activestate Perl 5.14 (Other/Commercial)] License Text () ActiveState Perl Dev Kit (PDK) License Agreement Please read carefully: THIS IS A LICENSE AND NOT AN AGREEMENT FOR SALE. By using and installing ActiveState Software Inc.’s Software or, where applicable, choosing the “I ACCEPT…” option at the end of the License you indicate that you have read, understood, and accepted the terms and conditions of the License. IF YOU DO NOT AGREE WITH THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS, YOU SHOULD NOT ATTEMPT TO INSTALL THE Software. If the Software is already downloaded or installed, you should promptly cease using the Software in any manner and destroy all copies of the Software in your possession.