MALWAREBYTES, INC., Defendant-Appellee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checks to Avoid Malware Protect Your Laptop with Security Essentials

What is Malware? Malware is software that can infect you computer and can be a virus or malicious software that can harm & slow your system or try to steal your personal information. To help avoid malware follow the check list below. Checks to avoid Malware Check you have updated Antivirus software installed such as Microsoft Security Essentials Install and run an Anti-Malware program such as Malwarebytes Uninstall any Peer 2 Peer software such as Limewire or Vuze Be careful with email attachments and never respond to mails asking for your password Protect your Laptop with Security Essentials Microsoft Security Essentials is a free antivirus software product for Windows Vista, 7 & 8. It pro- vides protection against different types of malware such as computer virus, spyware, rootkits, trojans & other malicious software. Download & install Security Essentials from the following link http:// www.microsoft.com/security_essentials/ Clear Infections using Malwarebytes Malware bytes is free to download & install from http://www.malwarebytes.org Once installed it is recommended that you run a Full Scan of your laptop to check for any malware that may reside on the system. Once complete, follow the on screen instructions to finish removing any threats found. You should regularly run updates and scans to ensure your system remains clean. It is also advisable to scan external storage devices such as USB keys as they can spread infections. If the above criteria are fully met, ISS staff at the service desk on the ground floor of the library are happy to investigate problems on your laptop For more information go to http://www.dcu.ie/iss ISS online service desk: https://https://iss.servicedesk.dcu.ie Follow ISS on Twitter @ISSservice . -

Hostscan 4.8.01064 Antimalware and Firewall Support Charts

HostScan 4.8.01064 Antimalware and Firewall Support Charts 10/1/19 © 2019 Cisco and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This document is Cisco public. Page 1 of 76 Contents HostScan Version 4.8.01064 Antimalware and Firewall Support Charts ............................................................................... 3 Antimalware and Firewall Attributes Supported by HostScan .................................................................................................. 3 OPSWAT Version Information ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Cisco AnyConnect HostScan Antimalware Compliance Module v4.3.890.0 for Windows .................................................. 5 Cisco AnyConnect HostScan Firewall Compliance Module v4.3.890.0 for Windows ........................................................ 44 Cisco AnyConnect HostScan Antimalware Compliance Module v4.3.824.0 for macos .................................................... 65 Cisco AnyConnect HostScan Firewall Compliance Module v4.3.824.0 for macOS ........................................................... 71 Cisco AnyConnect HostScan Antimalware Compliance Module v4.3.730.0 for Linux ...................................................... 73 Cisco AnyConnect HostScan Firewall Compliance Module v4.3.730.0 for Linux .............................................................. 76 ©201 9 Cisco and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This document is Cisco Public. -

Key Benefits Core Technologies and Technical Features

Advanced threat prevention Malwarebytes Endpoint Security is an innovative platform that delivers powerful multi- layered defense for smart endpoint protection. Malwarebytes Endpoint Security enables small and large enterprise businesses to thoroughly protect against the latest malware and advanced threats—including stopping known and unknown exploit attacks. Key Benefits Blocks zero-hour malware Easy management Reduces the chances of data exfiltration and saves Simplifies endpoint security management and identifies on IT resources by protecting against zero-hour vulnerable endpoints. Streamlines endpoint security malware that traditional security solutions can miss. deployment and maximizes IT management resources. Saves legacy systems Scalable threat prevention Protects unsupported programs by armoring Deploys protection for every endpoint and scales as vulnerabilities against exploits. your company grows. Increases productivity Detects unprotected systems Maintains end-user productivity by preserving Discovers all endpoints and installed software on your system performance and keeping staff on revenue- network. Systems without Malwarebytes that are positive projects. vulnerable to cyber attacks can be easily secured. Core Technologies and Technical Features Anti-Malware Proactive anti-malware/anti-spyware scanning Three system scan modes (Quick, Flash, Full) engine Enables selection of the most efficient system scan Detects and eliminates zero-hour and known based on endpoint security requirements and available viruses, Trojans, worms, rootkits, adware, and system resources. spyware in real time to ensure data security and network integrity. Extends its protection to Windows Server operating systems. | Santa Clara, CA | malwarebytes.com | [email protected] | 1.800.520.2796 Advanced threat prevention Malicious website blocking Advanced malware remediation Prevents access to known malicious IP addresses Employs delete-on-reboot to remove persistent or so that end users are proactively protected from deeply embedded malware. -

Q3 Consumer Endpoint Protection Jul-Sep 2020

HOME ANTI- MALWARE PROTECTION JUL - SEP 2020 selabs.uk [email protected] @SELabsUK www.facebook.com/selabsuk blog.selabs.uk SE Labs tested a variety of anti-malware (aka ‘anti-virus’; aka ‘endpoint security’) products from a range of well-known vendors in an effort to judge which were the most effective. Each product was exposed to the same threats, which were a mixture of targeted attacks using well-established techniques and public email and web-based threats that were found to be live on the internet at the time of the test. The results indicate how effectively the products were at detecting and/or protecting against those threats in real time. 2 Home Anti-Malware Protection July - September 2020 MANAGEMENT Chief Executive Officer Simon Edwards CONTENTS Chief Operations Officer Marc Briggs Chief Human Resources Officer Magdalena Jurenko Chief Technical Officer Stefan Dumitrascu Introduction 04 TEstING TEAM Executive Summary 05 Nikki Albesa Zaynab Bawa 1. Total Accuracy Ratings 06 Thomas Bean Solandra Brewster Home Anti-Malware Protection Awards 07 Liam Fisher Gia Gorbold Joseph Pike 2. Threat Responses 08 Dave Togneri Jake Warren 3. Protection Ratings 10 Stephen Withey 4. Protection Scores 12 IT SUPPORT Danny King-Smith 5. Protection Details 13 Chris Short 6. Legitimate Software Ratings 14 PUBLICatION Sara Claridge 6.1 Interaction Ratings 15 Colin Mackleworth 6.2 Prevalence Ratings 16 Website selabs.uk Twitter @SELabsUK 6.3 Accuracy Ratings 16 Email [email protected] Facebook www.facebook.com/selabsuk 6.4 Distribution of Impact Categories 17 Blog blog.selabs.uk Phone +44 (0)203 875 5000 7. -

American National Finishes the Job on Malware Removal Malwarebytes Leaves No Malware Remnants Behind

CASE STUDY American National finishes the job on malware removal Malwarebytes leaves no malware remnants behind Business profile INDUSTRY American National offers a wide range of life and property/casualty Financial services insurance products for more than 5,000 individuals, agribusiness, and commercial policyholders. Headquartered in Galveston, Texas, BUSINESS CHALLENGE American National employs 3,000 people, and is represented by Ensure that machines are completely free agents in all 50 states and Puerto Rico. When the IT team needed of malware a lightweight—but highly effective—remediation solution, it turned IT ENVIRONMENT to Malwarebytes. Cisco Advanced Malware Protection (AMP), Cylance, layered enterprise Malwarebytes Breach Remediation does security model a great job. In some cases, Cisco AMP or SOLUTION Cylance removed portions of malware but Malwarebytes Breach Remediation left remnants behind. Malwarebytes completely cleans things up. RESULTS —Fran Moniz, Network Security Architect, American National • Removed remnants of malware that other solutions missed • Simplified remediation for help Business challenge desk staff Malware is inevitable • Freed time for advanced security When Fran Moniz arrived at American National as its Network training and projects Security Architect, one of his first tasks was to streamline security platforms. He replaced McAfee and Symantec antivirus solutions with a Sophos product and augmented it with Cisco Advanced Malware Protection (AMP). A year later, he added Cylance threat prevention to the infrastructure. “Unfortunately, the antivirus solution interfered with both Cisco AMP and Cylance,” said Moniz. “When we ran them together, we experienced malware infections. I removed the antivirus and now rely on the other tools to protect us.” Cisco AMP runs on the company’s IronPort email gateways, and Moniz uses Cylance on company servers. -

PC Pitstop Supershield 2.0

Anti -Virus Comparative PC Matic PC Pitstop SuperShield 2.0 Language: English February 2017 Last Revision: 30 th March 2017 www.av-comparatives.org Commissioned by PC Matic - 1 - PC Pitstop – February 2017 www.av-comparatives.org Introduction This report has been commissioned by PC Matic. We found PC Matic PC Pitstop very easy to install. The wizard allows the user to change the location of the installation folder and the placing of shortcuts, but the average user only needs to click Next a few times. The program can be started as soon the setup wizard completes. A Different Approach PC Matic approaches security differently than traditional security products. PC Matic relies mainly on a white list to defeat malware; this can lead to a higher number of false alarms if users have files which are not yet on PC Matic’s whitelist. Unknown files are uploaded to PC Matic servers, where they get compared against a black- and white list (signed and unsigned). By default, PC Matic SuperShield only blocks threats and unknown files on-execution, but does not remove/quarantine them. Additional features In addition to malware protection, PC Matic also provides system maintenance and optimization features. These include checking for driver updates, outdated programs with vulnerabilities, erroneous registry entries and disk fragmentation. A single scan can be run which checks not only for malware, but also for any available system optimization opportunities. Commissioned by PC Matic - 2 - PC Pitstop – February 2017 www.av-comparatives.org Tested products The tested products have been chosen by PC Matic. We used the latest available product versions and updates available at time of testing (February 2017). -

Magic Quadrant for Endpoint Protection Platforms

Licensed for Distribution Magic Quadrant for Endpoint Protection By Peter Firstbrook, Dionisio Zumerle, Prateek Bhajanka, Lawrence Pingree, Paul Webber Platforms Published 20 August 2019 - ID G00352135 - 63 min read The endpoint protection market is transforming as new approaches challenge the status quo. We evaluated solutions with an emphasis on hardening, detection of advanced and fileless attacks, and response capabilities, favoring cloud-delivered solutions that provide a fusion of products and services. Strategic Planning Assumption By 2025, cloud-delivered EPP solutions will grow from 20% of new deals to 95%. Market Definition/Description This document was revised on 23 August 2019. The document you are viewing is the corrected version. For more information, see the Corrections page on gartner.com. An endpoint protection platform (EPP) is a solution deployed on endpoint devices to harden endpoints, to prevent malware and malicious attacks, and to provide the investigation and remediation capabilities needed to dynamically respond to security incidents when they evade protection controls. Traditional EPP solutions have been delivered via a client agent managed by an on-premises management server. More modern solutions utilize a cloud-native architecture that shifts the management, and some of the analysis and detection workload, to the cloud. Security and risk management leaders responsible for endpoint protection are placing a premium on detection capabilities for advanced fileless threats and investigation and remediation capabilities. Data protection solutions such as data loss prevention (DLP) and encryption are also frequently part of EPP solutions, but are considered by buyers in a different buying cycle. Protection for Linux and Mac is increasingly common, while protection for mobile devices and Chromebooks is increasing but is not typically considered a must-have capability. -

Is Antivirus Dead? Detecting Malware and Viruses in a Dynamic Threat Environment READER ROI Introduction

Is Antivirus Dead? Detecting Malware and Viruses in a Dynamic Threat Environment READER ROI Introduction Despite the presence of advanced antivirus In November 2015, Starwood Hotels and Resorts confirmed it had fallen victim to a solutions, cyber criminals continue to malware attack that spanned eight months and involved 54 locations. Infiltrating its launch successful attacks using increasingly sophisticated malware. Read this paper to network via point-of-sale (POS) channels within the chain’s restaurants and gift shops, learn: the malware stole payment card information, including card numbers, cardholder names, expiration dates, and security codes. • Why antivirus software is no longer effective in detecting, let alone stopping, most malware Less than a week later, Hilton Hotels and Resorts admitted to having suffered an almost identical malware breach in its own POS systems. And both entities are just the latest in a • Why a layered approach to cybersecurity offers more complete series of high profile breaches that range from well-known corporations such as Target to protection than antivirus or other the U.S. Office of Personnel Management. “silver bullet” solutions can on their own No wonder companies are fearful of becoming the next target, says Pedro Bustamente, • Why a malware hunting tool is Vice President of Technology at Malwarebytes. “Their worst fear is to have a situation like essential to detect any malware that a Target or a Home Depot, where they have been breached, don’t know about it for a breaches the network long time, and all of a sudden it comes out. Meanwhile, during the dwell time, the infection gathered customer information or internal information,” Bustamente explains. -

Malwarebytes for Windows User Guide Version 3.6.1 19 September 2018

Malwarebytes for Windows User Guide Version 3.6.1 19 September 2018 Notices Malwarebytes products and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. You may copy and use this document for your internal reference purposes only. This document is provided “as-is.” The information contained in this document is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, we would appreciate your comments; please report them to us in writing. The Malwarebytes logo is a trademark of Malwarebytes. Windows is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation. All other trademarks or registered trademarks listed belong to their respective owners. Copyright © 2018 Malwarebytes. All rights reserved. Third Party Project Usage Malwarebytes software is made possible thanks in part to many open source and third party projects. A requirement of many of these projects is that credit is given where credit is due. Information about each third party/open source project used in Malwarebytes software – as well as licenses for each – are available on the following page. https://www.malwarebytes.com/support/thirdpartynotices/ Sample Code in Documentation The sample code described herein is provided on an “as is” basis, without warranty of any kind, to the fullest extent permitted by law. Malwarebytes does not warrant or guarantee the individual success developers may have in implementing the sample code on their development platforms. -

Pikes Peak Library District Takes Malware out of Circulation Malwarebytes Provides Defense Without Compromising Openness

CASE STUDY Pikes Peak Library District takes malware out of circulation Malwarebytes provides defense without compromising openness Business profile INDUSTRY Pikes Peak Library District (PPLD) is a nationally recognized Government system of public libraries serving residents in El Paso County, Colorado. With fourteen facilities, online resources, and mobile BUSINESS CHALLENGE library service, PPLD responds to the unique needs of individual Prevent malware, including ransomware, neighborhoods and the community at large. A large number of from infecting computers while computers used by staf and patrons have internet connectivity. centralizing control To protect them from ransomware and other advanced malware, IT ENVIRONMENT PPLD chose Malwarebytes. Webroot antivirus, Deep Freeze Instant Restore Malwarebytes surpasses our antivirus’ SOLUTION prevention and detection features and runs Malwarebytes Endpoint Security with almost zero performance impact on users’ machines. RESULTS —Richard Peters, Chief Information Officer, • Stopped malware, including Pikes Peak Library District ransomware, from infecting computers • Significantly reduced labor costs Business challenge through better detection and Centralizing control over endpoints centralized management Four hundred and seventy-five PPLD employees operate library • Eliminated downtime and disruption facilities, manage book and media acquisition, and help patrons associated with malware find information. PPLD has 14 locations, plus a mobile Bookmobile and a Library Express kiosk. In addition to staf computers, PPLD provides computers for library patrons’ use. As an organization that exists to facilitate access to print, audio, visual, and electronic information, it’s not surprising that internet-based cyber threats target the browsers, Java, and Adobe Flash applications. Staf members encountered browser hijacking, popup ads, malicious email attachments, and drive-by downloads. -

Ryuk 04/08/2021

The Evolution of Ryuk 04/08/2021 TLP: WHITE, ID# 202104081030 Agenda • What is Ryuk? • A New Ryuk Variant Emerges in 2021 • Progression of a Ryuk Infection • Infection Chains • Incident: Late September Attack on a Major US Hospital Network • Incident: Late October Attack on US Hospitals • UNC1878 – WIZARD SPIDER • Danger to the HPH Sector • Mitigations and Best Practices • References Slides Key: Non-Technical: Managerial, strategic and high- level (general audience) Technical: Tactical / IOCs; requiring in-depth knowledge (sysadmins, IRT) 2 What is Ryuk? • A form of ransomware and a common payload for banking Trojans (like TrickBot) • First observed in 2017 • Originally based on Hermes(e) 2.1 malware but mutated since then • Ryuk actors use commercial “off-the-shelf” products to navigate victim networks o Cobalt Strike, Powershell Empire • SonicWall researchers claimed that Ryuk represented a third of all ransomware attacks in 2020 • In March 2020, threat actor group WIZARD SPIDER ceased deploying Ryuk and switched to using Conti ransomware, then resumed using Ryuk in mid-September • As of November 2020, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) estimated that victims paid over USD $61 million to recover files encrypted by Ryuk 3 A New Ryuk Variant Emerges in 2021 • Previous versions of Ryuk could not automatically move laterally through a network o Required a dropper and then manual movement • A new version with “worm-like” capabilities was identified in January 2021 o A computer worm can spread copies of itself from device to device -

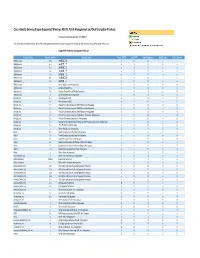

Cisco Identity Services Engine Supported Windows AV/AS/PM/DE

Cisco Identity Services Engine Supported Windows AS/AV, Patch Management and Disk Encryption Products Compliance Module Version 3.6.10363.2 This document provides Windows AS/AV, Patch Management and Disk Encryption support information on the the Cisco AnyConnect Agent Version 4.2. Supported Windows Antispyware Products Vendor_Name Product_Version Product_Name Check_FSRTP Set_FSRTP VirDef_Signature VirDef_Time VirDef_Version 360Safe.com 10.x 360安全卫士 vX X v v 360Safe.com 4.x 360安全卫士 vX X v v 360Safe.com 5.x 360安全卫士 vX X v v 360Safe.com 6.x 360安全卫士 vX X v v 360Safe.com 7.x 360安全卫士 vX X v v 360Safe.com 8.x 360安全卫士 vX X v v 360Safe.com 9.x 360安全卫士 vX X v v 360Safe.com x Other 360Safe.com Antispyware Z X X Z X Agnitum Ltd. 7.x Outpost Firewall Pro vX X X O Agnitum Ltd. 6.x Outpost Firewall Pro 2008 [AntiSpyware] v X X v O Agnitum Ltd. x Other Agnitum Ltd. Antispyware Z X X Z X AhnLab, Inc. 2.x AhnLab SpyZero 2.0 vv O v O AhnLab, Inc. 3.x AhnLab SpyZero 2007 X X O v O AhnLab, Inc. 7.x AhnLab V3 Internet Security 2007 Platinum AntiSpyware v X O v O AhnLab, Inc. 7.x AhnLab V3 Internet Security 2008 Platinum AntiSpyware v X O v O AhnLab, Inc. 7.x AhnLab V3 Internet Security 2009 Platinum AntiSpyware v v O v O AhnLab, Inc. 7.x AhnLab V3 Internet Security 7.0 Platinum Enterprise AntiSpyware v X O v O AhnLab, Inc. 8.x AhnLab V3 Internet Security 8.0 AntiSpyware v v O v O AhnLab, Inc.