INTERPRETING VIOLENCE: the STRUGGLE to UNDERSTAND the NATAL CONFLICT John Aitchison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of the Natal Witness

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF THE NATAL WITNESS by MARYLAWHON Submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of Master in Environment and Development in the Centre for Environment and Development, School ofApplied Environmental Sciences University ofKwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg 2004 ABSTRACT The media has had a significant impact on spreading environmental awareness internationally. The issues covered in the media can be seen as both representative of and an influence upon the heterogeneous public. This paper describes the environmental reporting in the South African provincial newspaper, the Natal Witness, and considers the results to both represent and influence South African environmental ideology. Environmental reporting In South Africa has been criticised for its focus on 'green' environmental issues. This criticism is rooted in the traditionally elite nature of both the media and environmentalists. However, both the media and environmentalists have been noted to be undergoing transformation. This research tests the veracity of assertions that environmental reporting is elitist, and has found that the assertions accurately describe reporting in the Witness. 'Green' themes are most commonly found, and sources and actors tend to be white and men. However, a broad range of discourses were noted, showing that the paper gives voice to a range of ideologies. These results hopefully will make a positive contribution to the environmental field by initiating debate, further studies, and reflection on the part of environmentalists, journalists, and academics on the relationship between the media and the South African environment. The work described in this dissertation was carried in the Centre for Environment and Development, University ofKwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, from July 2004 to December 2004, under the supervision ofProfessor Robert Fincham. -

A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo W Introduction and Summary of Lessons

Witness Apartheid: A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo w Introduction and Summary of Lessons . 3 Day One: Apartheid Simulation . ?C Day 'bo: Film-Witness to Apartheid . 7 Day Three: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" . 9 Day Four: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" (completion) . 11 Day Five: South Africa Letter Writing. 13 Reference Materials . 14 Additional Reading Suggestions for Student. Reading Suggestions for lkachers Additional Film Suggestions Student Handout #1 Privileged Minority. .......................... 15 Student Handout #2 The Bantustans . 16 Student Handout #3 Human Rights Fact Sheet. 17 Student Handout #4 Learning Was Defiance . 19 Student Handout #5 South African Student . 21 Student Handout #6 Challenging "Gutter Education". 23 a1987 Copyright by William Bigelow Published by The Southern Africa Media Center California Newsreel, 630 Natoma Street, San Francisco, CA 94103, (415) 621-6196 This "Raching Guide" made possible by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Design, typesetting, and production by Allogmph, San Francisco Film, Witness to Apartheid (classroom version): 35 minutes, 1986 Produced and directed by Sharon Sopher Co-produced by Kevin Harris Classroom version of Witness to Apartheid made possible by the Aaron Diamond Foundation. Introduction The story Witness to Apartheid tells is stark: children in South Africa - the same age as students we teach - are today being beaten, detained, even tortured. As one recent human rights report summarizes, the South African government is waging a 'kar against children.'' The images of Witness to Apartheid are not seen on the evening news: a father shares his feelings about the cold-blooded murder of his son by a South African policeman; a young woman describes the hideous torture she experienced while in police custody; a young man mumbles that he doesn't want to go on living - his beatings by security forces have left him permanently disabled. -

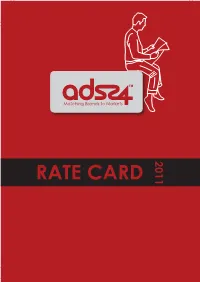

RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011

2011 RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011 Beeld (Mon, Tues) Beeld (Wed, Thurs, Fri) BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Beeld Main Body R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Beeld Main Body R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sport 24 R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Sport 24 R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 BEELD BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Jip R127.00 R172.50 R172.50 R172.50 Leefstyl R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Buite Beeld R146.10 R201.60 R201.60 R201.60 Motors R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Vrydag R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 BEELD Oos Beeld R 46.10 R 64.80 R 64.80 R 64.80 Tshwane Beeld R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Mpumalanga Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Noordwes Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Wes Beeld R 40.90 R 54.60 R 54.60 R 54.60 Huisgids R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Die Burger (Mon, Tues) Die Burger (Wed, Thurs, Fri) DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Burger Wes Main Body R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Main Body R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Promosies R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Promosies R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sport 24 R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Sport 24 R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Jip Wes R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Leefstyl -

Publications Brochure Newspapers

NEWS TRAVEL LIFESTYLE MEN SCIENCE & TECH WOMEN ENTERTAINMENTSPORT 2019 Beeld 3 Rapport 4 The Witness 5 NEWSPAPERS Sunday Sun 6 Daily Sun 7 Die Burger 8 Copyright © 2019 Media24 Volksblad 9 City Press 10 DistrictMail 11 Hermanus Times 12 Paarl Post 13 Weslander 14 Worcester Standard 15 3 Beeld is an award-winning Afrikaans newspaper that’s published six days a week in Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order Beeld Monday - R12.50 Gauteng R231 Monday - Friday Friday issue Beeld Monday - R12.50 Gauteng R280 Monday - Saturday Friday issue Saturday R13.50 Gauteng issue Beeld R12.50 Saturday only Gauteng R50 Saturday only Copyright © 2019 Media24 4 Rapport offers exclusive news on politics, sport and people, 16 pages with opinions, analyses and book reviews in Weekliks, lifestyle news in Beleef, business news in Sake, job opportunities in Loopbane and a newsmaker profile by Hanlie Retief. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order Rapport R12.50 Sunday only National R101 Copyright © 2019 Media24 5 The Witness is a broadsheet morning newspaper that’s published Monday to Friday in KwaZulu-Natal. Weekend Witness is a tabloid which appears on Saturdays and provides a mix of news, commentary, sport, personal finance, entertainment and a popular weekly property sales supplement. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order The Witness Monday - R7.70 KZN R119 Monday - Friday Friday issue The Witness Monday - R7.70 KZN R144 Monday - Saturday Friday issue Saturday R7.90 KZN issue The Witness R7.90 Saturday only KZN R25 Saturday only Copyright © 2019 Media24 6 Sunday Sun is an exciting Sunday tabloid filled with entertainment and lots of celebrity news. -

South African Crime Quarterly 57

The killing fields of KZN Local government elections, violence and democracy in 2016 Mary de Haas* [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2016/v0n57a456 This article explores the intersections between party interests, democratic accountability and violence in KwaZulu-Natal. It begins with an overview of the legacy of violence in the province before detailing how changes in the African National Congress (ANC) since the 2007 Polokwane conference are inextricably linked to internecine violence and protest action. It focuses on the powerful eThekwini Metro region, including intra-party violence in the Glebelands hostel ward. These events provide a crucial context to the violence preceding the August 2016 local government elections. The article calls for renewed debate about how to counter the failure of local government. In KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), the province dubbed the Glebelands hostel ward. Crucially, it also the ‘killing fields’ in the early 1990s, all post- contextualises the violence that preceded the 1994 elections have been marked by intimidation August 2016 local government elections. and violence. In the past decade intra-party Political violence 1994–2015 conflict, especially over the nomination of local government ward candidates, has increased. The violence that engulfed KZN in the 1980s In 2011 the conflict within the African National and early 1990s continued for several years Congress (ANC) went beyond individual after the 1994 elections, with an estimated competition and was symptomatic of increasing -

The Mess Camille PAGE 2 PAGE 3 PAGE 10

KZN is Mopping up There’s just bleeding no stopping the mess Camille PAGE 2 PAGE 3 PAGE 10 THURSDAY, JULY 15, 2021 R9,20 (incl vat) More SANDF personnel seen arriving in Pietermaritzburg on The Alan Paton Drive yesterday. PHOTO: NASH NARRANDES WitnessWitness Substantial losses to businesses paint a gloomy future ‘My father’s CLIVE NDOU have been left devastated by the looting. We While the situation remained gloomy, Zika- would today finalise a plan on how the shorta- “The fact of the matter is that we don’t witnessed the massive damage to property. lala said the provincial government was en- ges could be mitigated. While those who have have any areas which are preserved for a par- people are The KwaZulu-Natal economy has suffered Some of the looting happened whilst we were couraged by the work being done by law en- been looting businesses and vandalising prop- ticular race group. What we have are areas for damage worth around R3 billion since the on- there,” he said. forcement agencies to stop the looting and erty have claimed that they were engaged in all South Africans,” he said. going riots started on Friday. In Cato Ridge Zikalala came face to face with vandalism. a protest against the imprisonment of former Zikalala’s update on the provincial govern- committing This is according to KZN Premier Sihle Zika- the looters while they were busy stealing from “The situation would have been much worse president Jacob Zuma, Zikalala labelled the ment’s response to the looting and vandalism lala, who revealed that Pietermaritzburg and the Value Logistics warehouse. -

Albert Luthuli: Bound by Faith'

H-SAfrica Soske on Couper, 'Albert Luthuli: Bound by Faith' Review published on Friday, January 4, 2013 Scott Couper. Albert Luthuli: Bound by Faith. Scottsville, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2010. Illustrations. xi + 291 pp. $45.00 (paper), ISBN 978-1-86914-192-9. Reviewed by Jon Soske (McGill University) Published on H-SAfrica (January, 2013) Commissioned by Alex Lichtenstein Since its publication in 2010, Scott Couper’s biography, Albert Luthuli: Bound by Faith, has been at the center of academic and public controversy, including a fiery exchange with Raymond Suttner in the pages of the South African Historical Journal and a critique by the current South African president, Jacob Zuma. Albert Luthuli served as the African National Congress (ANC) president from 1952 to his death in 1967, a period during which the ANC first emerged as a truly mass organization and, following the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960, remade itself into an underground organization for the purposes of armed struggle. Internationally respected during his lifetime, Luthuli embodied the democratic aspirations of many South Africans well beyond his death and remains a central figure in the national pantheon of the post-apartheid state. The debates over Luthuli’s legacy are therefore closely tied to the ANC’s efforts to ground its legitimacy as a ruling party in a particular narrative of the past and the enormous symbolic importance of the 1950s, the period when many of the canonical figures, ideas, and symbolism of today’s party first emerged. The contentious issue is Luthuli’s attitude toward the formation of the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), and the “turn to violence” of late 1961. -

Activities at the University of Natal at Pietermaritzburg

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 359 818 FL 800 595 AUTHOR Van Heerden, Gwyneth; And Others TITLE Empowering Adults through Literacy Education inSouth Africa: Activities at the University ofNatal at Pietermaritzburg. REPORT NO ISSN-1016-3435 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 8p.; NU Focus is published by the Universityof Natal. AVAILABLE FROMPublic Affairs Department, University ofNatal, P.O. Box 375, Pietermaritzburg 3200, South Africa. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) Information Analyses (070) JOURNAL CIT NU Focus; v2 n3 p29-37 Win 1991 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; *African Languages; Blacks; *English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; Illiteracy; LiteracyEducation; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Learning; Uncommonly Taught Languages IDENTIFIERS Empowerment; *South Africa; University of Natal (South Africa); Zulu ABSTRACT Five brief articles froma journal published by the Public Affairs Department of the Universityof Natal, South Africa, discuss issues related to empoweringadults through literacy education in that country. "Meeting Needs" (Gwynethvan Heerden) describes the extent and nature of adultilliteracy in South Africa and the activities of the literacysupport service of the Center for Adult Education at the University ofNatal. "Read for Life" (Tania Spencer) describes acourse aimed at teaching adults how to read and write in Zulu using the learning/experiencemethod. "A Leg to Stand On" (Vis Naidoo) presents the Learnwith Echo project, which provides distance basic adult educational materialfor a black undereducated readership. "Meeting Needs" (Vis Naidoo)describes the goals and philosophy of the Center for Adult Education'sCommunity Development Education and Training Programme. "Offthe Shelf" (Tania Spencer) describes a special library establishedby the University of Natal's Department of Information Studies and NatalSociety Library, which is designed to facilitate community andindividual empowerment. -

Print This Article

doi: 10.5789/3-1-16 Global Media Journal African Edition 2009 Vol 3 (1) A democratised market? Development of South Africa's daily newspapers 1990 - 2006 Tobias Bauer Abstract This article looks at the development of the South African daily newspaper market between 1990 and 2006. The leading interest is to find out whether the market was able to develop from its apartheid-trenched roots, and in which areas the market is still influenced by its specific past. The market determinants, namely participants, growth, entrance barriers, distribution, readership, economic and editorial concentration, will be scrutinised over the 16 years. The relevant political, economical and legal background and the transformations taking place in these areas will be articulated. The data will reveal that by growing more and more, especially since the turn of the century, the market enables itself to break free from its old structure. This is mainly due to the successful introduction of new papers which break with the traditional orientation of South African papers towards a wealthy readership and thus win new readers for the product newspaper in general. 1. Apartheid, newspapers and media policy The control of information via the media was important in the implementation and preservation of apartheid. The government did not want the Blacks to be informed about black leaders and politics; neither should the international community be informed about the injustices of apartheid. The regime applied a variety of laws to secure agreeable reporting and influenced media opinion by simply operating the media themselves (Hachten & Giffard, 1984:113-124). In its attitude towards the press, the apartheid regime revealed two differing faces: towards the English-language press the regime was very coercive, for it regarded the English-language press as its greatest enemy in the country (Hachten & Giffard, 1984:3). -

AVERAGE ISSUE READERSHIP of NEWSPAPERS and MAGAZINES the “AMPS® Jan-Dec ‘09” Was the First 12 Month Full DS-CAPI Database

AVERAGE ISSUE READERSHIP OF NEWSPAPERS AND MAGAZINES The “AMPS® Jan-Dec ‘09” was the first 12 month full DS-CAPI database. As a result of methodological changes introduced with DS-CAPI, the readership data is not comparable with that of previous surveys. The following table gives the latest readership figures for newspapers and magazines from SAARF AMPS Jan-Dec ‘10. Over and above the thousands of readers and percentages of the total adult population for each publication, the table also indicates the range (both in percentages and thousands) in which the true readership figure lies, with a statistical certainty of 95%. Let us look at two examples: Example 1 - Beeld (daily) - 506,000 readers, 1.5% of total adults – AMPS Jan-Dec ‘10. The table indicates that there is a range of plus or minus 0.15%; and plus or minus 51,000 readers. This means that we can be 95% certain that the true value of Beeld lies somewhere in the range (1.5 – 0.15% to 1.5 + 0.15%, that is, 1.35% to 1.65%) or (506,000 – 51,000 to 506,000 + 51,000, that is, 455,000 to 557,000 readers). Example 2 – Daily Sun – 5,023,000 readers, 14.8% of total adults – AMPS Jan-Dec ‘10. The table indicates that there is a range of plus or minus 0.44%; and plus or minus 149,000 readers. We can, therefore, be 95% certain that the true range of Daily Sun lies in the range (14.8 – 0.44% to 14.8 + 0.44%, that is, 14.36% to 15.24%) or (5,023,000 – 149,000 to 5,023,000 + 149,000, that is, 4,874,000 to 5,172,000 readers). -

Beverley Muller Zulu and the Media: a Success Story in Africa

CIEA7 #26: MODERNIDADES Y MEDIA. Beverley Muller [email protected] Zulu and the media: a success story in Africa This research paper examines the prevalence and expansion, in the media, of Zulu, one of South Africa’s eleven official languages. Zulu is an indigenous African language spoken mainly in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. There are 10,677,000 Zulu speakers in South Africa. This community represents 23.8% of South Africa’s total population of 44,820,000 (2001 census). This is the biggest language group in the country and is followed by the Xhosa language group of 7,907,000 persons comprising 17,6% of the population. The third biggest linguistic group is Afrikaans with 5,983,000 people accounting for 13,3% of the population. In the KwaZulu- Natal province of South Africa 80% of the population is Zulu speaking. Migration, Technology, Transnacionalism, Sociabilities. Senior Lecturer. School of IsiZulu - University of KwaZulu Natal. Zulu is one amongst very few indigenous African languages used as a language medium for a daily paper on the African continent. The daily paper referred to is ‘Isolezwe’ meaning ‘the eye of the country’. This newspaper was first printed relatively recently in 2002. Zulu is also used as the language medium for two Sunday newspapers, ‘Isolezwe ngeSonto’ meaning ‘The eye of the country on Sunday’ and ‘Ilanga Langesonto’ meaning ‘The Sun on Sunday’. Another Zulu language newspaper, ‘Ilanga’, meaning ‘Sun’ or ‘Day’, is produced twice a week. ‘Ilanga’ was first produced in 1903 by Dr John Dube, the founder of the African National Congress, the political movement which won the first democratic election in South Africa in 1994 and formed the first democratic government of South Africa under President Nelson Mandela. -

The African Patriots, the Story of the African National Congress of South Africa

The African patriots, the story of the African National Congress of South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The African patriots, the story of the African National Congress of South Africa Author/Creator Benson, Mary Publisher Faber and Faber (London) Date 1963 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 968 B474a Description This book is a history of the African National Congress and many of the battles it experienced.