A Case Study of the Awutu Breku District by Vida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Page LIST OF ACRONYMS a EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Scope of Study 1 1.2 Background – Volta River Authority 2 1.3 Proposed Aboadze-Volta Transmission Line Project (AVTP) 3 1.4 Legal, Regulatory and Policy Considerations 5 1.5 Future developments by VRA 8 2.0 Description of proposed development 10 2.1 Pre-Construction Activities 11 2.2 Construction Phase Activities 12 2.3 Operational Phase Activities 17 2.3.1 Other Operational Considerations 20 3.0 Description of Existing Environments 21 3.1 Bio-Physical Environment 21 3.1.1 Climate 21 3.1.2 Flora 25 3.1.3 Fauna 35 3.1.4 Water Resources 43 3.1.5 Geology and Soils 44 3.1.6 General Land Use 51 3.2 Socio-Economic/Cultural Environment 51 3.2.1 Methodology 53 3.2.2 Profiles of the Districts in the Project Area 54 3.2.2(a) Shama - Ahanta East Metropolitan Area 54 3.2.2(b) Komenda - Edina - Eguafo - Abirem (KEEA) District 58 i 3.2.2(c) Mfantseman District 61 3.2.2(d) Awutu-Effutu-Senya District 63 3.2.2(e) Tema Municipal Area 65 3.2.2(f) Abura-Asebu-Kwamankese 68 3.2.2(g) Ga District 71 3.2.2(h) Gomoa District 74 3.3 Results of Socio-Economic Surveys 77 (Communities, Persons and Property) 3.3.1 Information on Affected Persons and Properties 78 3.3.1.1 Age Distribution of Affected Persons 78 3.3.1.2 Gender Distribution of Affected Persons 79 3.3.1.3 Marital Status of Affected Persons 80 3.3.1.4 Ethnic Composition of Afected Persons 81 3.3.1.5 Household Size/Dependents of Affected Persons 81 3.3.1.6 Religious backgrounds of Affected Persons 82 3.3.2 Economic Indicators -

Ghana Gazette

GHANA GAZETTE Published by Authority CONTENTS PAGE Facility with Long Term Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 1236 Facility with Provisional Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 201 Page | 1 HEALTH FACILITIES WITH LONG TERM LICENCE AS AT 12/01/2021 (ACCORDING TO THE HEALTH INSTITUTIONS AND FACILITIES ACT 829, 2011) TYPE OF PRACTITIONER DATE OF DATE NO NAME OF FACILITY TYPE OF FACILITY LICENCE REGION TOWN DISTRICT IN-CHARGE ISSUE EXPIRY DR. THOMAS PRIMUS 1 A1 HOSPITAL PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI KUMASI KUMASI METROPOLITAN KPADENOU 19 June 2019 18 June 2022 PROF. JOSEPH WOAHEN 2 ACADEMY CLINIC LIMITED CLINIC LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE MAMPONG KUMASI METROPOLITAN ACHEAMPONG 05 October 2018 04 October 2021 MADAM PAULINA 3 ADAB SAB MATERNITY HOME MATERNITY HOME LONG TERM ASHANTI BOHYEN KUMASI METRO NTOW SAKYIBEA 04 April 2018 03 April 2021 DR. BEN BLAY OFOSU- 4 ADIEBEBA HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG-TERM ASHANTI ADIEBEBA KUMASI METROPOLITAN BARKO 07 August 2019 06 August 2022 5 ADOM MMROSO MATERNITY HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI BROFOYEDU-KENYASI KWABRE MR. FELIX ATANGA 23 August 2018 22 August 2021 DR. EMMANUEL 6 AFARI COMMUNITY HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI AFARI ATWIMA NWABIAGYA MENSAH OSEI 04 January 2019 03 January 2022 AFRICAN DIASPORA CLINIC & MATERNITY MADAM PATRICIA 7 HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI ABIREM NEWTOWN KWABRE DISTRICT IJEOMA OGU 08 March 2019 07 March 2022 DR. JAMES K. BARNIE- 8 AGA HEALTH FOUNDATION PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI OBUASI OBUASI MUNICIPAL ASENSO 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 DR. JOSEPH YAW 9 AGAPE MEDICAL CENTRE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI EJISU EJISU JUABEN MUNICIPAL MANU 15 March 2019 14 March 2022 10 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION -ASOKORE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE KUMASI METROPOLITAN 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION HOSPITAL- DR. -

Ghana Marine Canoe Frame Survey 2016

INFORMATION REPORT NO 36 Republic of Ghana Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development FISHERIES COMMISSION Fisheries Scientific Survey Division REPORT ON THE 2016 GHANA MARINE CANOE FRAME SURVEY BY Dovlo E, Amador K, Nkrumah B et al August 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................... 2 LIST of Table and Figures .................................................................................................................... 3 Tables............................................................................................................................................... 3 Figures ............................................................................................................................................. 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 BACKGROUND 1.2 AIM OF SURVEY ............................................................................................................................. 5 2.0 PROFILES OF MMDAs IN THE REGIONS ......................................................................................... 5 2.1 VOLTA REGION .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 GREATER ACCRA REGION ......................................................................................................... -

Awutu Senya District Assembly

THE COMPOSITE BUDGET OF THE AWUTU SENYA DISTRICT ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2013 FISCAL YEAR For copies of this MMDA’s Composite Budget, please contact the address below: The Coordinating Director, Awutu Senya District Assembly Central Region This 2013 Composite Budget is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh or www.ghanadistricts.com Awutu Senya District Assembly Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: ASSEMBLY’S COMPOSITE BUDGET STATEMENT……………………......25 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 3 Key Strategies within the Medium Term Development Plan and in line with GSGDA ....................................................................................................................... 9 STATUS OF THE 2012 COMPOSITE BUDGET IMPLEMENTATION ............... 15 Financial Performance: Revenue ...................................................................... 15 NON- FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE (ASSETS) ..................................................... 17 2013-2015 MTEF COMPOSITE BUDGET PROJECTION ................................ 20 Challenges and Constraints .............................................................................. 25 JUSTIFICATION OF 2013 BUDGET ................................................................... 27 SECTION II: ASSEMBLY’S DETAIL COMPOSITE BUDGET…………………………......38 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Population (Structure) ............................................................................. 4 Table 2: Public Schools ........................................................................................ -

Ghana Poverty Mapping Report

ii Copyright © 2015 Ghana Statistical Service iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ghana Statistical Service wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the Government of Ghana, the UK Department for International Development (UK-DFID) and the World Bank through the provision of both technical and financial support towards the successful implementation of the Poverty Mapping Project using the Small Area Estimation Method. The Service also acknowledges the invaluable contributions of Dhiraj Sharma, Vasco Molini and Nobuo Yoshida (all consultants from the World Bank), Baah Wadieh, Anthony Amuzu, Sylvester Gyamfi, Abena Osei-Akoto, Jacqueline Anum, Samilia Mintah, Yaw Misefa, Appiah Kusi-Boateng, Anthony Krakah, Rosalind Quartey, Francis Bright Mensah, Omar Seidu, Ernest Enyan, Augusta Okantey and Hanna Frempong Konadu, all of the Statistical Service who worked tirelessly with the consultants to produce this report under the overall guidance and supervision of Dr. Philomena Nyarko, the Government Statistician. Dr. Philomena Nyarko Government Statistician iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

The Awutu-Effutu-Senya District

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh The S o c io -E c o n o m ic Effects o f C o m m er cia l Pin ea pple Fa rm in g o n Farm Em plo yees a n d C om m unities in THE AWUTU-EFFUTU-SENYA DISTRICT C ollins O sae ID#: 10174261 This D issertation is S ubm itted t o the Un iv e r sity o f G h a n a , L e g o n in P a r t ia l F u lfilm en t o f the R e q u ir em en t f o r the A w a r d o f M A D e v e lo p m e n t S tu dies D e g r e e May 2005 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh (J374483 $2>V£-Osl bite, C-\ University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh D e c l a r a t io n I hereby declare that except for acknowledged references, this work is the result of my own research. It has never been presented anywhere, either in part or in its entirety, for the award of any degree. Collins Osae Prof. John Kwasi Anarfi Main Supervisor University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh D e d ic a t io n I dedicate this work to all young people desiring to maximise their academic potentials through higher education. University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh A cknowledgments I remain forever grateful to God for granting me this rare opportunity to unearth a hidden potential. -

Awutu Senya West District Assembly

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE COMPOSITE BUDGET OF THE AWUTU SENYA WEST DISTRICT ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2014 FISCAL YEAR 1 For Copies of this MMDA’s Composite Budget, please contact the address below: The Coordinating Director, Awutu Senya West District Assembly Central Region This 2014 Composite Budget is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh 2 1.0 Vision and Mission 1.1 Vision: The Awutu Senya District Assembly aspires to become attractive centre for modernized agriculture, brisk commerce and a knowledge-based society in which all men, women and children are capable of utilizing available potentials and opportunities to contribute to development. 1.2 Mission: The District Assembly exists to facilitate improvement of the quality of life of the people within the Assembly’s jurisdiction through equitable provision of services for the total development of the district, within the context of Good Governance. 2.0 Brief Profile (Analysis of economic activities and progress so far) 2.1 Introduction: The current Awutu Senya District Assembly has been split by LI 2025 of 6th February 2012 into Awutu Senya East Municipal and the Awutu Senya District Assemblies. It performs the functions conferred on District Assemblies by the Local Government Act, 1993, Act 462 and LI 2024 of February, 2012. The Awutu Senya District is situated between latitudes 5o20’N and 5o42’N and longitudes 0o25’W and 0o37’W at the eastern part of the Central Region of Ghana. It is bordered by the Awutu Senya East Municipal and Ga South Municipal (in the Greater Accra Region) to the east; Effutu Municipal and the Gulf of Guinea to the south; the West Akim District to the north; Agona East and Birim South to the north-west, Agona West District to the west, and the Gomoa East separating the southern of the District from the main land. -

Analysing the Challenges Associated with Infrastructural

ANALYSING THE CHALLENGES ASSOCIATED WITH INFRASTRUCTURAL PROJECT EXECUTION IN THE AWUTU SENYA DISTRICT ASSEMBLY BY Richard Odei Akrofi (BSc. Public Administration) A Thesis submitted to the Department of Construction Technology and Management, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT NOVEMBER, 2019 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the thesis. Richard Odei Akrofi (PG5321318) ……………………… ………..…………. (Name of student and ID) Signature Date Certified by. Dr. Kofi Agyekum …….………….……… …….………..…… (Supervisor) Signature Date Certified by. Prof. B.K Baiden ……………………… …………………… (Name of Head of Department) Signature Date ii DEDICATION To the Almighty God. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT All Glory and honour be to the Most High God for bringing me this far in my life. Without him, I wouldn‟t have been able to make it to this far. Posterity will not forgive me if I fail to acknowledge the immense contribution of my supervisor, Dr. Kofi Agyekum for his guidance in the conduct of this work. To the study respondents, I am very grateful for your time. I also thank all the lecturers of the Department of Construction Technology and Management for the knowledge they have imparted to me. -

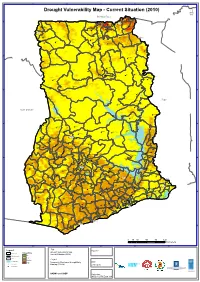

Drought Vulnerability

3°0'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°0'0" 1°0'0"E Drought Vulnerability Map - Current Situation (2010) ´ Burkina Faso Pusiga Bawku N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Gwollu Paga ° 1 1 1 1 Zebilla Bongo Navrongo Tumu Nangodi Nandom Garu Lambusie Bolgatanga Sandema ^_ Tongo Lawra Jirapa Gambaga Bunkpurugu Fumbisi Issa Nadawli Walewale Funsi Yagaba Chereponi ^_Wa N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 0 1 1 Karaga Gushiegu Wenchiau Saboba Savelugu Kumbungu Daboya Yendi Tolon Sagnerigu Tamale Sang ^_ Tatale Zabzugu Sawla Damongo Bole N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 9 9 Bimbila Buipe Wulensi Togo Salaga Kpasa Kpandai Côte d'Ivoire Nkwanta Yeji Banda Ahenkro Chindiri Dambai Kintampo N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 8 Sampa 8 Jema Nsawkaw Kete-krachi Kajeji Atebubu Wenchi Kwame Danso Busunya Drobo Techiman Nkoranza Kadjebi Berekum Akumadan Jasikan Odumase Ejura Sunyani Wamfie ^_ Dormaa Ahenkro Duayaw Nkwanta Hohoe Bechem Nkonya Ahenkro Mampong Ashanti Drobonso Donkorkrom Nkrankwanta N N " Tepa Nsuta " 0 Va Golokwati 0 ' Kpandu ' 0 0 ° Kenyase No. 1 ° 7 7 Hwediem Ofinso Tease Agona AkrofosoKumawu Anfoega Effiduase Adaborkrom Mankranso Kodie Goaso Mamponteng Agogo Ejisu Kukuom Kumasi Essam- Debiso Nkawie ^_ Abetifi Kpeve Foase Kokoben Konongo-odumase Nyinahin Ho Juaso Mpraeso ^_ Kuntenase Nkawkaw Kpetoe Manso Nkwanta Bibiani Bekwai Adaklu Waya Asiwa Begoro Asesewa Ave Dapka Jacobu New Abirem Juabeso Kwabeng Fomena Atimpoku Bodi Dzodze Sefwi Wiawso Obuasi Ofoase Diaso Kibi Dadieso Akatsi Kade Koforidua Somanya Denu Bator Dugame New Edubiase ^_ Adidome Akontombra Akwatia Suhum N N " " 0 Sogakope 0 -

The Operationalization of the Dlrev Software for Improved Revenue Mobilization at Local Government Level: a Cost-Benefit Analysis

THE OPERATIONALIZATION OF THE DLREV SOFTWARE FOR IMPROVED REVENUE MOBILIZATION AT LOCAL GOVERNMENT LEVEL: A COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS GOVERNANCE FOR INCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT / SUPPORT FOR DECENTRALISATION REFORMS (SFDR) DEUTSCHE GESELLSCHAFT FÜR INTERNATIONALE ZUSAMMENARBEIT (GIZ) GMBH NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLANNING COMMISSION COPENHAGEN CONSENSUS CENTER © 2020 Copenhagen Consensus Center [email protected] www.copenhagenconsensus.com This work has been produced as a part of the Ghana Priorities project. Some rights reserved This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution Please cite the work as follows: #AUTHOR NAME#, #PAPER TITLE#, Ghana Priorities, Copenhagen Consensus Center, 2020. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0. Third-party-content Copenhagen Consensus Center does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within the work. If you wish to re-use a component of the work, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that re-use and to obtain permission from the copyright owner. Examples of components can include, but are not limited to, tables, figures, or images. PRELIMINARY DRAFT AS OF MAY 18, 2020 The operationalization of the dLRev software for improved revenue mobilization at local government level: a cost-benefit analysis Ghana Priorities Governance For Inclusive Development / Support for Decentralisation Reforms (SfDR), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Copenhagen Consensus Center Academic Abstract Revenue mobilization and management are critical to local government service delivery. Whereas traditional practices emphasized personal interactions and manual record- keeping, geospatial data, internet and information networks have the power to streamline these municipal processes. -

Awutu Senya District Assembly Annual Progress

AWUTU SENYA DISTRICT ASSEMBLY IMPLEMENTATION OF DISTRICT MEDIUM-TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2014-2017) ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT FOR 2016 PREPARED BY: DISTRICT PLANNING COORDINATING UNIT TABLE OF CONTENT 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………..1 Methods of Data Collection for the Report………………………………….1 Mission and Vision…………………………………………………………..2 2.0 District profile ……………………………………………………………………...3 Topography and Drainage …………………………………………………..3 Climate ……………………………………………………………………...3 Vegetation …………………………………………………………………..4 Soil Characteristics …………………………………………………………4 DA Structure – No of DA Members, Sub-structures ……………………….4 Area of coverage ……………………………………………………………5 Population (Structure) ………………………………………………………5 District Economy …………………………………………………………...5 Environmental Sanitation…………………………………………………...6 Tourism……………………………………………………………………..6 Education …………………………………………………………………...6 Analysis of Health …………………………………………………….........7-8 Assembly’s Strategic Direction 2014-1016 ………………………………...9 Twenty (20) Core Indicators…………………………………………….....9-11 3.0 Performance ………………………………………………………........................12 Physical Projects ……………………………………………………….......12 Status of the Projects ……………………………………………………….12 Location of Projects…………………………………………………………13 Year of projects..……………………………………………………………14 Contract Sum of Projects……………………………………………………14 Project type ……………………………………………………………........15 Project sector ……………………………………………………………….15 Categories of Projects……………………………………………………….16 Funding Sources …………………………………………………………....16 Challenges ………………………………………………………………….17 -

Teacher Licensing Centres and Locations Central Region

TEACHER LICENSING CENTRES AND LOCATIONS CENTRAL REGION TEACHER LICENSING CENTRES AND LOCATIONS (JUNE 2021) CENTRAL REGION DATES MMDs CENTRE NAMES DIRECTIONS 01/06 & AWUTU ST. MARTHA'S CATHOLIC BASIC ON OBOM ROAD BEFORE 02/06 SENYA BAWJIASE JN, THEN TURN EAST RIGHT FROM RENT CONTROL BUILDING 01/06 & AWUTU ODUPONGKPEHE M/A BASIC ON NYANYANO ROAD NEAR 02/06 SENYA SCHOOL CANTEEN THE FIRST TRAFFIC LIGHT EAST 01/06 & AWUTU ST.MARY'S ANGLICAN JHS KASOA BAWJIASE ROAD 02/06 SENYA EAST DATES MMDs CENTRE NAMES DIRECTIONS 01/06 & AWUTU ODUPONG SHS FROM St, MARY'S ANGLICAN 02/06 SENYA CONTINUE TO OFAAKOR & EAST BRANCH LEFT 01/06 & AWUTU BAWJIASE METHODIST BASIC BAWJIASE TOWNSHIP 02/06 SENYA SCH WEST 01/06 & AWUTU BAWJIASE D/A BASIC SCH BAWJIASE TOWNSHIP 02/06 SENYA WEST 01/06 & AWUTU DISTRICT EDUCATION ON AWUTU- 02/06 SENYA CONF.HALL BEREKU/BONTRASE RD WEST CLOSE TO THE COURT 01/06 & AWUTU OBRAKYIRE D/A SCH ON THE AWUTU/BREKU- 02/06 SENYA BONTRASE ROAD WEST 01/06 & GOMOA EAST THE HARTLEY TRUST BRANCH LEFT AT KASOA 02/06 FOUNDATION SCH TO NYANYANO 01/06 & GOMOA EAST ST. GREGORY CATH. BUDUBURAM ON THE 02/06 CHURCH KASOA WINNEBA ROAD 01/06 & GOMOA EAST OJOBI D/A BASIC AT AKOTSI JN. AFTER 02/06 SCH BUDUBURAM ASK OF DIRECTION TO OJOBI 01/06 & GOMOA EAST POTSIN METHODIST AT GOMOA POTSIN ON 02/06 CHURCH THEKASOA WINNEBA ROAD DATES MMDs CENTRE NAMES DIRECTIONS 03/06 & AGONA WEST SWEDRU EMMANUEL NEAR SWEDRU ESG 04/06 METHODIST CHURCH OFFICE (POWER HOUSE) 03/06 & AGONA WEST SWEDRU SDA CLOSE TO SWEDRU PIPE 04/06 CHURCH TANK 03/06 & AGONA WEST NYAKROM NEAR NYAKROM 04/06 METHODIST CHURCH VICTORIA PARK 03/06 & AGONA WEST FANKOBAA SHS FROM NYAKROM, TURN 04/06 LEFT TO BOBIKUMA, THEN LEFT TO FANKOBAA SHS 03/06 & AGONA EAST NSABA PRESBY AGONA NSABA 04/06 CHURCH 03/06 & AGONA EAST DUAKWA PRESBY AGONA DUAKWA 04/06 CHURCH 03/06 & AGONA EAST NAMANWORA COMM.