The Decay of Hot KK Space Arxiv:1408.5903V2 [Hep-Th] 30 Apr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brian May Plays “God Save the Queen” from the Roof of Buckingham Palace to Commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’S Golden Jubilee on June 3, 2002

Exclusive interview Brian May plays “God Save the Queen” from the roof of Buckingham Palace to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee on June 3, 2002. © 2002 Arthur Edwards 26 Astronomy • September 2012 As a teenager, Brian Harold May was shy, uncer- tain, insecure. “I used to think, ‘My God, I don’t know what to do, I don’t know what to wear, I don’t know who I am,’ ” he says. For a kid who didn’t know who he was or what he wanted, he had quite a future in store. Deep, abiding interests and worldwide success A life in would come on several levels, from both science and music. Like all teenagers beset by angst, it was just a matter of sorting it all out. Skiffle, stars, and 3-D A postwar baby, Brian May was born July 19, 1947. In his boyhood home on Walsham Road in Feltham on the western side of Lon- science don, England, he was an only child, the offspring of Harold, an electronics engineer and senior draftsman at the Ministry of Avia- tion, and Ruth. (Harold had served as a radio operator during World War II.) The seeds for all of May’s enduring interests came early: At age 6, Brian learned a few chords on the ukulele from his father, who was a music enthusiast. A year later, he awoke one morning to find a “Spanish guitar hanging off the end of my bed.” and At age 7, he commenced piano lessons and began playing guitar with enthusiasm, and his father’s engineering genius came in handy to fix up and repair equipment, as the family had what some called a modest income. -

Bakalářská Práce 2012

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at University of West Bohemia Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce 2016 Martina Veverková Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce THE ROCK BAND QUEEN AS A FORMATIVE FORCE Martina Veverková Plzeň 2016 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – němčina Bakalářská práce THE ROCK BAND QUEEN AS A FORMATIVE FORCE Vedoucí práce: Mgr. et Mgr. Jana Kašparová Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2016 ……………………… I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. et Mgr. Jana Kašparová for her advice which have helped me to complete this thesis I would also like to thank my friend David Růžička for his support and help. Table of content 1 Introduction ...................................................................... 1 2 The Evolution of Queen ................................................... 2 2.1 Band Members ............................................................................. 3 2.1.1 Brian Harold May .................................................................... 3 2.1.2 Roger Meddows Taylor .......................................................... 4 2.1.3 Freddie Mercury -

Group 3: Jennifer Day, Xander Jarnow, Duke Mcghee, Shelby Stehn, Adam Vandenhouten, Tyler Kallevig Reasons Why We Chose Queen

Queen Group 3: Jennifer Day, Xander Jarnow, Duke McGhee, Shelby Stehn, Adam Vandenhouten, Tyler Kallevig Reasons Why We Chose Queen: There are a lot of reasons that we, as a group, decided to do our project on Queen. Queen is an extremely well-known band across multiple generations, so it is an artist that we can talk to almost anyone anywhere about. Additionally, they were an influence to many artists after them. Finally, they released over 15 albums that showed a very impressive musical range and an awe-inspiring amount of talent. Queen: Overview Queen was one of the most popular and successful rock groups during the 1970s and 80s, with a very unique, experimental style and sound, Queen has remained one of the best selling artists of all time. The band began its formation in 1967, when the guitarist Brian May and the drummer Roger Taylor joined with Tim Staffell to form a rock group named Smile. When Tim Staffell left the group, May and Taylor joined forces with Freddie Mercury and a bass player named John Deacon, resulting in the core version of the band in 1970. Queen was famous for bright, glam, “pomp-rock” and put on energetic shows. Freddie Mercury in particular was known for his flamboyant style. Their sound was a very produced and incorporated elements of glam rock, heavy metal, hard rock, and harmony. After the tragic death of Freddie Mercury the band added new members and continued performing Even today their songs remain popular, for example, “We Are the Champions,” “Another One Bites the Dust,” “Bohemian Rhapsody,” and “We Will Rock You” are still played often. -

QUEEN-Britanska Rokovska Skupina

QUEEN-britanska rokovska skupina • Razpad skupine SMILE- Brian May (kitarist) in Roger Taylor (bobni) • progresivni rock, heavy metal in glam rock. ZASEDBA • John Deacon • Brian May • Freddie Mercury • Roger Taylor John Brian May Deacon -rojen 1947 -glavni kitarist skupine -rojen 1951 -pogosto sodeloval kot -bas kitarist spremljevalni vokal -igral tudi klavir Roger Taylor -glavni vokal v -rojen 1949 nekaterih pesmih -bobnar -Red Special -pel glavni vokal pri večini svojih pesmi FREDDIE MERCURY • 5. september 1946-Stone Town • Farrokh Bulsara • 1965 Queen • Glavni vokalist-frontman • Avtor številnih pesmi (greatest hits) • Glas s širokim razponom • Montserrat Caballe-Barcelona • 1965-1991 • 1987 je zbolel za Aidsom • 24. november 1991 -London ZAŠČITNI ZNAK • Queen crest • Narisal Freddie Mercury ZGODOVINA • 1974 Seven Seas of Rhye- Queen II • največja uspešnica Bohemian Rhapsody-Night at the Opera • 1992 Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert • John Deacon upokojil 1997 • Taylor in May sodelovala s Paulom Rodgersom - Queen + Paul Rodgers ALBUMI HIT SINGLI • Queen(1973) • Bohemian Rhapsody (1975) • Queen II (1974) • We Will Rock You (1977) • Sheer Heart Attack(1974) • We Are the Champions (1977) • A Night at the Opera (1975) • Bicycle Race (1978) • A Day at the Races (1976) • Don't Stop Me Now (1978) • News of the World (1977) • Another one Bites the Dust(1980) • Jazz (1978) • Crazy Little Thing Called Love (1980) • Live Killers (1979) • Flash's Theme (Flash Gordon) (1980) • The Game (1980) • Under Pressure (Queen & David Bowie) • Flash Gordon -

THE OFFICIAL INTERNATIONAL QUEEN FAN CLUB Winter 2012

THE OFFICIAL INTERNATIONAL QUEEN FAN CLUB Winter 2012 Editorial Hi Everyone! NOTES FROM GREG BROOKS elcome to the Winter issue of the fan club magazine! As I write it‘s certainly winter QUEEN ARCHIVIST. of the montages covers an area of 12 feet across by 7 feet, Where, freezing cold, and one little snow so that’s 84 square feet of ‘Works’ memorabilia in this case shower shut the UK own, as usual! I hope you are all s I write, we are working on a new presentation - hence even a very large 5’ x 8’ poster seems relatively small warm and well if you are sharing our weather (or of the 1974 Rainbow concerts – possibly a in the mix, when in fact it’s a signifi cant size. worse!). And if you are enjoying sunshine and heat- A new edit of the November shows, distilling both I was really pleased with the 21 montages we shot, and waves... I‘m SO jealous! into one, and looking at the audio from the March concert though each one took hours to set up and shoot, I’m glad we It‘s been a great Queen fi lled year hasn‘t it?! With va- and seeing what we can do with that - as well as the limi- spent that kind of time on them because we were acutely rious CD and DVD releases, and the excellent live ted video from that night too. We are searching like mad aware we’d only get one chance to do this to this scale and shows! And for those in North America, the highly ac- for more footage from that night, since every fan I know detail. -

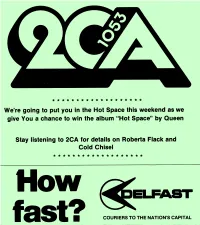

2CA Chart, 1982-05-21

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * We're going to put you in the Hot Space this weekend as we give You a chance to win the album "Hot Space" by Queen Stay listening to 2CA for details on Roberta Flack and Cold Chisel * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * How fast? COURIERS TO THE NATION'S CAPITAL Music Survey 21ST MAY, 1982 LAST LAST SINGLES WEEK ALBUMS WEEK 1. I LOVE ROCK'N'ROLL Joan Jett & the Blackhearts (1) 1. 1982 WITH A BULLET Various (1) (EMI) LS 678 (EMI) GIVE 2005 2. EBONY & IVORY Paul McCartney (2) 2. CHARIOTS OF FIRE Vangelis (4) (EMI) A 698 (POL) 2383 602 3. MICKEY Toni Basil (6) 3. HIT WAVE '82 Various (2) (RCA) POW 0035 (POLY) HIT 82 4. CHARIOTS OF FIRE Vangelis (12) 4. DAYS OF INNOCENCE Moving Pictures (5) (POL) 2059 341 (EMI) WBEX-1005 5. LOVE PLUS ONE Haircut One Hundred (25) 5. CIRCUS ANIMALS Cold Chisel (3) (FEST) K 8656 (WEA) 600113 6. JUST CAN'T GET ENOUGH Depeche Mode (3) 6. THE CONCERT IN CENTRAL PARK Simon & Garfunkel (9) (RCA) POW 0053 (CBS) 2GHS 2012 7. WHAT ABOUT ME Moving Pictures (4) 7. TIME & TIDE Split Enz (6) {EMI) WBE 648 (FEST) RML 53012 8. BODY AND SOUL Jo Kennedy (31) 8. DARE Human League (8) (FEST) K8621 (CBS) V 2192 9. GOLDEN BROWN The Stranglers (11) 9. BUSINESS AS USUAL Men At Work (7) (EMI) UA650 (CBS) SBP 7700 10. FOREVER NOW Cold Chisel (5) 10. I LOVE ROCK'N ROLL Joan Jett & the Blackhearts (12) (WEA) 100202 (EMI) LIB-5009 11. CENTREFOLD J. Geils Band (7) 11. -

PDF Download Queen: the Complete Works Ebook

QUEEN: THE COMPLETE WORKS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Georg Purvis | 440 pages | 13 Mar 2012 | Titan Books Ltd | 9780857685513 | English | London, United Kingdom Queen: The Complete Works PDF Book Retrieved 3 October Archived from the original on 28 January Archived from the original PHP on 18 August Soul Brother Written-By — Queen. Calling All Girls 9. Queen II. Sell This Version. Australia Kent Music Report [20]. Most expensive items sold in Discogs Marketplace for March by discogs. Readers also enjoyed. Main article: Love Kills Freddie Mercury song. Mercury played piano and did most of the vocals, and instructed May about the scales he should use for the solo, described by May in the guitar programme Star Licks as very " Bohemian Rhapsody "- esque. It was still credited to Taylor since Mercury was an arranger rather than a co-writer. Flash To The Rescue. Written by May some time in , the song was recorded during the album sessions but never made it onto the final cut. Mark rated it it was amazing Nov 19, Someone who's not a fan probably wouldn't get much out of this book. Cool Cat White Man 8. OK: on the one hand, this is clearly an ambitious project. ETA: And since I haven't read it cover to cover, I'm not counting it in my self-imposed book goal for ; I've upped the number to , and I'll just call it Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. The best part about this book is the fact that each and every thing about The Best Companion to Queen's Music! The Works. -

Dead on Time

Queen FOUR VISIONS song song song song song song with our keyword song with our keyword song with our keyword song with our keyword song with our keyword 1973 1974 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1980 1980 1982 1984 1985 1986 1988 1989 1991 1995 1997 1998 1973 1974 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1980 1980 1982 1984 1985 1986 1988 1989 1991 1995 1997 1998 1973 1974 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1980 1980 1982 1984 1985 1986 1988 1989 1991 1995 1997 1998 1973 1974 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1980 1980 1982 1984 1985 1986 1988 1989 1991 1995 1997 1998 1973 1974 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1980 1980 1982 1984 1985 1986 1988 1989 1991 1995 1997 1998 JAZZ JAZZ JAZZ JAZZ JAZZ QUEEN QUEEN QUEEN QUEEN QUEEN QUEEN II QUEEN II QUEEN II analysis of significant words QUEEN II QUEEN II THE GAME THE GAME THE GAME THE GAME INNUENDO INNUENDO INNUENDO INNUENDO HOT SPACE HOT SPACE HOT SPACE HOT THE GAME HOT SPACE HOT INNUENDO THE WORKS THE WORKS THE WORKS BARCELONA BARCELONA BARCELONA HOT SPACE HOT THE WORKS BARCELONA THE WORKS BARCELONA THE MIRACLE THE MIRACLE THE MIRACLE THE MIRACLE THE MIRACLE ELECTRIC FIRE ELECTRIC FIRE ELECTRIC QUEEN ROCKS QUEEN ROCKS QUEEN ROCKS ELECTRIC FIRE ELECTRIC ELECTRIC FIRE ELECTRIC QUEEN ROCKS KIND OF MAGIC KIND OF MAGIC KIND OF MAGIC KIND OF MAGIC FLASH GORDON FLASH GORDON FLASH GORDON QUEEN ROCKS ELECTRIC FIRE ELECTRIC FLASH GORDON KIND OF MAGIC FLASH GORDON MADE IN HEAVEN MADE IN HEAVEN MADE IN HEAVEN MADE IN HEAVEN MADE IN HEAVEN COMPLETE VISION COMPLETE VISION COMPLETE VISION COMPLETE VISION COMPLETE VISION A DAY AT THE RACES AT A DAY THE RACES -

A.Q.F.C.V. Austrian Queen Fan Club Vienna WIENER GESCHICHTEN – QUEEN UND FREDDIE MERCURY in WIEN

A.Q.F.C.V. Austrian Queen Fan Club Vienna WIENER GESCHICHTEN – QUEEN UND FREDDIE MERCURY IN WIEN Besondere, enge Beziehung zu Wien Queen und Freddie Mercury hatten schon immer eine ganz besondere, enge Beziehung zu Wien. Dies zeigt sich dadurch, dass sie auf ihren Tourneen immer wieder in Wien spielten, einige Promotion-Videos in Wien drehten und auch sonst sehr mit der Stadt verbunden waren. Live In Vienna Queen spielten mit Freddie sieben Mal in Wien, mit Paul Rodgers zwei Mal und mit dem neuen Gastsänger Adam Lambert ist für den 01.02.2015 wieder eine Liveshow in der Wiener Stadthalle geplant. Auch wenn Freddie Mercury nicht mehr mit der Band auf der Bühne stehen kann, gibt es keine Queen + Show ohne ihn. Freddie singt am Videoscreen „Love Of My Life“ und „Bohemian Rhapsody“ und ist in Foto- und Videozuspielungen während der Show immer wieder präsent. Das erste Mal in Wien Queen spielten das erste Mal bei der „News Of The World-Tour“ am 02.05.1978 in der Stadthalle. Das Highlight war eine lange Version von „Spread Your Wings“, welche Freddie mit „You call it Wien – we call it Vienna!” ankündigte. Hot Space in Vienna 4 Jahre später spielten Queen wieder in Wien. Diesmal jedoch bereits zwei Mal in der ausverkauften Stadthalle. Das Doppelkonzert der „Hot Space Tour“ fand am 12. und 13.05.1982 statt. Bei diesem Wienaufenthalt bezogen Queen vorerst das Hotel Intercontinental, wechselten jedoch sofort ins Hotel Imperial. Dort entstand ein berühmtes Promofoto mit Spiegeln und Kristallluster. Könige im Bild und Ton Der Showbeginn am 12.05.1982 in der Stadthalle mit „Flash“ sowie die Zugaben "Another One Bites The Dust (Freddie im Bademantel) / We Will Rock You / We Are The Champions / God Save The Queen" wurden von DoRo Productions - besser bekannt als das Wiener Videoproduzenten-Duo Rudi Dolezal und Hannes Rossacher - gefilmt. -

The Queen Discography Completa (1973-1991) Aggiornata (1992-2020)

The Queen Discography Completa (1973-1991) Aggiornata (1992-2020) - Studio Albums: Queen (13 Jul 1973) Queen II (8 Mar 1974) Sheer Heart Attack (8 Nov 1974) A Night At The Opera (21 Nov 1975) A Day At The Races (10 Dec 1976) News Of The World (28 Oct 1977) Jazz (10 Nov 1978) The Game (27 Jun 1980) Flash Gordon (8 Dec 1980) Hot Space (21 May 1982) The Works (27 Feb 1984) A Kind Of Magic (3 Jun 1986) The Miracle (22 May 1989) Innuendo (5 Feb 1991) Made In Heaven (6 Nov 1995) - Live Albums: Live Killers (rec: Jan–Mar 1979) (22 Jun 1979) Live Magic (rec: July–Aug 1986) (1 Dec 1986) At The Beeb (rec: 5 Feb & 3 Dec 1973) (4 Dec 1989) Live At Wembley '86 (rec: 12 Jul 1986) (26 May 1992) Queen On Fire – Live At The Bowl (rec: 5 Jun 1982) (4 Nov 2004) Queen Rock Montreal (rec: 24 & 25 Nov 1981) (29 Oct 2007) Hungarian Rhapsody: Queen Live In Budapest (rec: 27 Jul 1986) (20 Sep 2012) Live At The Rainbow '74 (rec: 31 Mar, 19 & 20 Nov 1974) (8 Sep 2014) A Night At The Odeon – Hammersmith 1975 (rec: 24 Dec 1975) (20 Nov 2015) On Air (rec BBC: Feb 1973 - Oct 1977) (4 Nov 2016) - Singles: Keep Yourself Alive / Son And Daughter (6 Jul 1973) Seven Seas Of Rhye / See What A Fool I've Been * (25 Feb 1974) Killer Queen / Flick Of The Wrist (single version) * (11 Oct 1974) Now I'm Here / Lily Of The Valley (single edit) * (17 Jan 1975) Bohemian Rhapsody (single edit) * / I'm In Love With My Car (single version) * (31 Oct 1975) You're My Best Friend / ‘39 (single edit) * (18 Jun 1976) Somebody To Love / White Man (19 Nov 1976) Tie Your Mother Down (single -

The Official International Queen Fan Club | Summer 2015 Well, the Years Roll By, Folks

QUEEN The Official International Queen Fan Club | Summer 2015 Well, the years roll by, folks. Roger and I, along with Adam and the whole Queen Team, are starting to prepare mentally for our swing through South America next month. Amazing that we should be still thundering around the world crashing through herds of Queen songs with that phenomenal GFG Adam Lambert. Well, yes, it’s hard to talk sense these days. In my view, the world has gone mad. or someone’s Compassion is a lost concept, all decisions are made on the basis of how they affect ‘The Economy’ personal wealth and power, and selfishness—the F—k You philosophy—rules. So here I am, ranting on as I do. But I’m a musician, right? Yes, we’ll be seeing you out there in Sao Paulo and Rio and Buenos Aires and Santiago and Cordoba and Porto Alegre … how thrilling. It’s almost exactly 30 years since we headlined the very first Rock in Rio night—with Freddie, and John, of course, and now we return to a new young audience of rockers, with Adam, who I’m convinced they will adore. It was all sold out From the ‘One Voice’ video—see https://youtu.be/0plWNDyA6Ig months ago, so it ought to be wild. Behind the scenes, Queen activity is always in full swing. The chaps have been working on a new Hi Everyone! historical venture Queen at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1975. This concert was very special because it was the first time we ever played a whole show completely live onTV … the Christmas Show. -

Made in Heaven Album Queen Download Made in Heaven Album Queen Download

made in heaven album queen download Made in heaven album queen download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66abc1365f643a6b • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Made in heaven album queen download. CD tracks 12 and 13 are not included in the track listing. Although "Untitled", they have, colloquially and even according to official sources, subsequently come to be known as "Yeah!" and "Track 13" (or just plain "13"), respectively. Excerpt from 'Goin' Back' courtesy of Gerry Goffin and Carole King. ℗ 1995 The copyright in this sound recording is owned by Queen Productions Ltd. under exclusive licence to EMI Records Ltd. © 1995 Queen Productions Ltd. Made in heaven album queen download. Queen - Made in Heaven (2011) Ten months after the release of the 1991 album Innuendo, Freddie Mercury died of complications brought on by AIDS; he was 45. To this day, most people hold Innuendo dear to their hearts because it was such a solid finale with one of rock's greatest frontmen.